Association Between Joint Hypermobility Syndrome and Panic Disorder

Abstract

Objective:The purpose of this study was to assess whether joint hypermobility syndrome is more frequent in patients with panic disorder, agoraphobia, or both than in control subjects and, if so, to determine whether mitral valve prolapse modifies or accounts in part for the association.Method:A case-control study was conducted in a general teaching hospital outpatient clinic. Subjects were 99 patients, newly diagnosed and untreated, with panic disorder, agoraphobia, or both and two groups of age- and sex-matched control subjects: 99 psychiatric patients and 64 medical patients who had never suffered from any anxiety disorder. Measures consisted of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, Beighton’s criteria for joint hypermobility syndrome, and two-dimensional and M-mode echocardiogram. The presence of mitral valve prolapse and joint hypermobility syndrome was explored by raters who were blind to subjects’ psychiatric status.Results:Joint hypermobility syndrome was found in 67.7% of patients with anxiety disorder but in only 10.1% of psychiatric and 12.5% of medical control subjects. On the basis of statistical analysis, patients with anxiety disorder were over 16 times more likely than control subjects to have joint laxity. These findings were not altered after the presence of mitral valve prolapse was taken into account. Of the patients with anxiety disorder, those who had joint hypermobility syndrome were younger and more often women and had an earlier onset of the disorder than those without joint hypermobility syndrome. Conclusions:Joint laxity is highly prevalent in patients with panic disorder, agoraphobia, or both and may reflect a constitutional disposition to suffer from anxiety. Mitral valve prolapse plays a secondary role in the association between joint hypermobility and anxiety. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155: 1578-1583

Over the last two decades a significant amount of research has been conducted into the neurobiological mechanisms of anxiety, and especially of panic disorder (1, 2). Among the biological variables studied in patients with panic disorder, mitral valve prolapse and the joint hypermobility syndrome have yielded particularly interesting results (3, 4). Mitral valve prolapse is the most common abnormality of the heart valves in industrialized nations, affecting 3% or more of the adult population (5). An association between mitral valve prolapse and panic disorder, in both directions, has been described by different authors (3, 6, 7). The two conditions share similar subjective complaints (palpitations, chest pain, dyspnea, fatigue, dizziness, and anxiety), an asthenic somatotype (8–10), and demographic features (e.g., both are more frequent in women) (11, 12). A meta-analysis of empirical studies concluded that a significant association exists between panic disorder and mitral valve prolapse (odds ratio=2.3; 95% confidence interval=1.6-3.5) (13).

Joint hypermobility syndrome is a highly heritable clinical condition characterized by an increased distensibility of joints in passive movements and hypermobility in active movements (14–16). Its prevalence in the general population appears to range between 10% and 15%, and it is more common in women than in men. A significant association between joint hypermobility syndrome and mitral valve prolapse has been described (17, 18). Furthermore, subjects with joint hypermobility syndrome and mitral valve prolapse appear to be about three times more likely to suffer from anxiety disorders than subjects with joint hypermobility syndrome without mitral valve prolapse (4). These studies have suggested that mitral valve prolapse and joint hypermobility syndrome may share a common pathophysiologic mechanism related to a collagen disorder (16, 18–22). In addition, a significant association between joint hypermobility syndrome and panic disorder was observed in a sample of rheumatologic outpatients (4, 23). Patients with joint laxity had a higher prevalence of anxiety disorders, in particular, panic disorder and phobias, than comparison subjects.

Therefore, there are numerous separate observations linking joint hypermobility syndrome to mitral valve prolapse and mitral valve prolapse to panic disorder, but little is known about the relation between joint hypermobility syndrome and panic disorder. The present study was designed to answer two specific questions: 1) Is joint hypermobility syndrome more common in patients with panic disorder than among appropriate comparison subjects? 2) If so, does mitral valve prolapse modify or partly account for the association between joint hypermobility syndrome and panic disorder?

METHOD

A case-control study was carried out at the Hospital del Mar, a 450-bed general teaching hospital, serving primarily a low-income area of Barcelona, Spain. All newly diagnosed consecutive patients who attended the psychiatric outpatient clinic over a 2-year period and who fulfilled DSM-III-R criteria for panic disorder or agoraphobia were selected as cases. Two control groups were selected. The first group was gathered from the same psychiatric outpatient population and included newly diagnosed consecutive patients who did not suffer from panic or agoraphobia and who had never met criteria for anxiety disorder. The second control group was recruited from four medical outpatient clinics (dermatology, gastroenterology, general surgery, and internal medicine) at the same hospital. Two hundred sixty-two subjects were studied: 99 case subjects, 99 psychiatric control subjects, and 64 medical control subjects. The last group originally included 99 patients, but all those found to suffer from anxiety disorder at the time of inclusion or in the past were subsequently excluded. All control subjects were matched to case subjects by age and sex.

Exclusion criteria included organic brain syndromes, psychoactive abuse disorders (except nicotine abuse), and severe organic conditions that hamper physical examination (the last in order to allow for a full joint examination). Because some of the questionnaires were self-administered, illiterate patients also had to be excluded. None of the subjects (case and control subjects) was taking psychotropic drugs at entry into the study.

All subjects gave informed consent. Group size was calculated by standard methods (24). The protocol was piloted for 3 months to ascertain the reliability of the instruments.

Two experienced psychiatrists used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (25) to establish the psychiatric diagnosis. Interrater reliability (kappa) for psychiatric diagnosis ranged between 0.65 and 1.00. Several psychometric instruments were also used, including the Index of Stress Reactivity (26), the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (27), and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (28, 29).

To assess joint hypermobility syndrome, Beighton criteria (15, 16) were used. Subjects who scored 5 or higher on the 9-point scale of Beighton were considered to have joint hypermobility. The reliability and validity of the assessment criteria for joint hypermobility syndrome have been previously described (30). In summary, the interrater reliability (kappa) of the five criteria ranged between 0.79 and 0.93, and concurrent validity with other sets of joint hypermobility syndrome criteria varied between 95.4% and 96.7% (proportion of well-classified cases). Joint hypermobility syndrome assessment was carried out by two trained rheumatologists who were blind to patients’ psychiatric status.

After psychopathological and rheumatological assessment, all case and control subjects were evaluated by a cardiologist who was unaware of their psychiatric and rheumatological status. A diagnosis of mitral valve prolapse was made on the basis of 1) two-dimensional echocardiographic evaluation (abnormal superior systolic movement of mitral valve leaflets and mitral valve prolapse buckling below the level of the annular plane into the left atrium) (31), and 2) M-mode evaluation (systolic posterior motion ≥3 mm) (32).

In contingency tables, Pearson’s chi-square test for homogeneity or independence was applied to assess the relationship between two qualitative or categorical variables. In two-by-two chi-squares, the Yates-corrected chi-square is presented. When 20% or more of the cells had expected counts of less than five, Fisher’s exact test was used (33). Student’s t test and one-factor analysis of variance were used to determine the relationship between a categorical variable with two or three levels, respectively, and a normally distributed quantitative variable; the Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze nonnormally distributed quantitative variables (34). The logit estimator of the prevalence odds ratio was estimated with precision-based confidence intervals (35). The logit estimators used the Haldane correction of 0.5 in every cell when a table contained a zero (35). Data management and statistical analysis were carried out on a Macintosh Centris 660 AV computer through use of SAS/JMP and Statview 4.01.

RESULTS

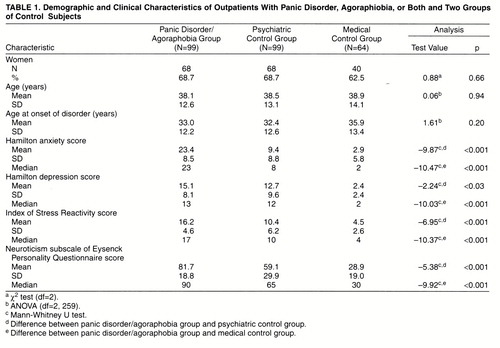

The mean age of the 262 subjects was 38.5 years (SD=13.1); 67.2% were women. Case and control subjects did not differ by age and sex because of the matching; neither did they differ by age at onset of disorders (table 1).

Seventy-six percent of case subjects were given diagnoses of panic disorder with agoraphobia; 17%, panic disorder without agoraphobia; and 7%, agoraphobia alone. The distribution of agoraphobic severity was as follows: 45%, light; 31%, moderate; and 24%, severe. Thirty-one percent of case subjects had a concomitant diagnosis of major depression or dysthymia. In the psychiatric control group, 23.8% of patients had schizophrenia; 61.4%, affective disorders; and 14.8%, miscellaneous conditions. In the medical control group, 29.8% of patients had digestive illnesses; 23.4%, other medical problems; 23.4%, surgical conditions; and 23.4%, dermatological complaints. Case subjects scored significantly higher than both psychiatric and medical control subjects on all psychiatric scales (table 1).

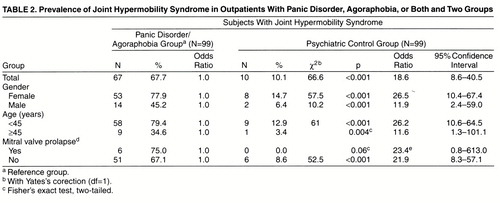

The mean Beighton scores (range=0–9) were 5.4 (SD=2.8) for the case subjects, 2.0 (SD=2.1) for the psychiatric control group, and 2.0 (SD=2.5) for the medical control group (F=57.14, df=2,<ths>259, p<0.001). The joint hypermobility syndrome was thus much more common among case subjects (67.7%) than among psychiatric control subjects (10.1%) (p<0.001) and medical control subjects (12.5%) (p<0.001). The corresponding prevalence odds ratios were 18.6 and 14.7 (table 2). Hence, case subjects were over 16 times more likely than control subjects to present the joint hypermobility syndrome.

Results of the echocardiographic examination were available for 84 (84.9%) of the 99 case subjects with anxiety disorder, 74 (74.8%) of the 99 psychiatric control subjects, and 34 (53.1%) of the 64 medical control subjects. Some case subjects refused the examination because of phobic fears, and some control subjects did not attend the examination despite two formal appointments, one by phone. Mitral valve prolapse was present in eight case subjects (9.5%), four psychiatric control subjects (5.4%), and six medical control subjects (17.7%). The differences between case subjects and the two control groups were not statistically significant (Yates-corrected χ2=0.45, df=1, p=0.50; and p=0.22, Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed, respectively).

Stratified analyses by gender, age group, and mitral valve prolapse all showed highly significant differences between case subjects and the two control groups (table 2). Whereas the higher prevalence of joint hypermobility syndrome among case subjects was statistically significant in all groups, the association was even stronger among women and among younger subjects. Over 70% of women with anxiety disorders had joint laxity, and the corresponding odds ratio was above 20. Similarly, case subjects younger than 45 years were over 20 times more likely to have the joint hypermobility syndrome than their control subjects.

Mitral valve prolapse did not substantially modify the association between joint hypermobility syndrome and anxiety: the odds ratios for subjects with and without prolapse were very similar (table 2). Mitral valve prolapse was not a confounder of the association between hypermobility and anxiety: mitral prolapse-adjusted odds ratios were all very close to the unadjusted estimates shown in table 2.

Among case subjects with anxiety disorder, we compared the groups with and without joint hypermobility. Differences emerged in age and gender: mean age for the group with hypermobility was 34.3 years (SD=10.8), whereas in the group without hypermobility it was 46.1 years (SD=12.4) (t=–4.8, df=97, p<0.001). There was a greater proportion of women among the hypermobility than the nonhypermobility subjects (79.1% versus 20.9%) (Yates-corrected χ2=9.01, df=1, p=0.001). With respect to panic symptoms, statistical differences between the hypermobility and nonhypermobility subjects were found only in the item “chills or hot flushes” (71.4% versus 28.6%) (Yates-corrected χ2=12.67, df=1, p<0.001). Number of symptoms (mean=8.2, SD=2.0, versus mean=7.6, SD=2.3) (t=1.24, df=91, p=0.22) and total phobia score (mean=23.3, SD=15.7, versus mean=23.6, SD=17) (t=–0.9, df=97, p=0.93) were not statistically different. Nevertheless, panic patients with hypermobility had an earlier onset of disorder than panic patients without hypermobility (mean=29.6 years, SD=10.5, versus mean=40.2, SD=12.7) (t=–4.38, df=97, p<0.001) and a higher score on the Hamilton anxiety scale (mean=25.6, SD=7.7, versus mean=19.0, SD=8.6) (z=–3.39, p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of the joint hypermobility syndrome in subjects with panic disorder was 67.7%, a figure significantly higher than that observed both in the psychiatric control group (10.1%) and among medical control subjects (12.5%). The last two figures are similar to those found in the general population (10%–15%) (15). Women and younger subjects with anxiety disorders were found to be over 20 times more likely to have the joint hypermobility syndrome than their corresponding control subjects. The magnitude of the association is uncommon in medical research; in our view, it clearly indicates that a causal connection may exist between the two conditions. To our knowledge, this is the first report on the joint hypermobility syndrome in anxiety patients. Previously, we had shown a high prevalence of panic and other anxiety disorders (69.3%) among patients with joint laxity who attended a rheumatological outpatient clinic (4). DSM-III-R diagnoses of panic disorder, agoraphobia, and simple phobia, but not generalized anxiety disorder, were found to be highly associated with joint hypermobility syndrome (4). Indirect evidence was provided only by one study on the prevalence of mitral valve prolapse in patients with panic disorder (36), which reported that 23% showed some extracardiac pathology of mitral valve prolapse that included hypermobility of joints, wall thoracic abnormalities, and arched oral palate.

The direction of the association between panic disorder/agoraphobia and joint hypermobility syndrome is as yet unclear. First, there is little evidence that panic leads to joint laxity; in clinical practice it is very difficult to find young panic patients who do not meet criteria for joint laxity. The opposite (i.e., joint laxity preceding panic) seems more plausible, since hypermobility of joints is present from early childhood. On the other hand, not all subjects who meet clinical criteria for joint laxity will suffer from panic or agoraphobia (4). Intermediate variables such as early life stressors, fear experiences, and separation anxiety may also be important in the development of panic (37, 38). Relaxation techniques and active exercise training, both intervening at the muscle-tendon level, also show some beneficial effect in panic disorder (39). Finally, panic and joint laxity could belong to a physical genetic locus that is phenotypically expressed at different life stages.

The prevalence of mitral valve prolapse in clinic groups of patients with panic attack is reported to range widely, from 0% to 50% (3, 13). In our study the prevalence of mitral valve prolapse was 8%, a figure considerably higher than that for the general population, possibly because ours was a hospital-based study. Nevertheless, our results did not point toward significant differences in the prevalence of mitral valve prolapse in anxiety and control subjects.

Apart from the fact that the panic group with joint hypermobility contained a greater proportion of younger and female subjects, this group was clinically very similar to the panic group without joint hypermobility. Only earlier age at onset and higher scores on some anxiety measures were found as differences. Furthermore, because joint hypermobility syndrome is more difficult to elicit as age increases, it may well be that the panic subjects without joint hypermobility syndrome had the syndrome when they were younger; because of the cross-sectional nature of the present study, we cannot answer this question. Overall, the similarities between panic patients with and without joint laxity were more striking than the differences. Therefore, at this stage of research, the value of joint hypermobility syndrome seems closer to a group marker than to a panic subtype marker.

The study has several limitations. The medical group was smaller than the two psychiatric groups. Mitral valve prolapse could not be assessed in all patients. Finally, as in all hospital-based studies, Berkson’s bias might account in part for the findings (40). Therefore, the results need to be replicated in a sample from the general population. On the other hand, the strengths of the study include selection of newly diagnosed patients; blind rating of mental disorders and of joint hypermobility syndrome; standardized assessment of psychiatric diagnosis, joint hypermobility syndrome, and mitral valve prolapse; matching by age and gender; and strong statistical power.

In summary, we observed a strong association between panic disorder and agoraphobia and joint hypermobility syndrome. This finding confirms our previous observations in rheumatologic patients and indicates the interest of assessing joint hypermobility syndrome as a constitutional characteristic in panic and agoraphobic patients. Whether joint hypermobility syndrome is in any way associated with neurotransmitter dysfunction, autonomic dysregulation, or a physical genetic locus remains to be elucidated.

Received Nov. 14, 1997; revision received April 13, 1998; accepted May 15, 1998. From the Departments of Psychiatry, Cardiology, and Rheumatology, Hospital del Mar; Institut Municipal d’Investigació Mèdica, Universidat Autònoma de Barcelona; and Centre de Salut de Sant Pere de Riudebitlles, Barcelona, Spain. Address reprint requests to: Dr. Martín-Santos, Department of Psychiatry, Hospital del Mar-IMIM. Passeig Marítim 25-29. E-08003-Barcelona, Spain. Supported in part by Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria grant 90/0123 to Institut Municipal d'Investigació Mèdica and Hospital del Mar, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain.

|

|

1. Klein DF: Panic disorder and agoraphobia: hypothesis hothouse. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 6):21–27Google Scholar

2. Kristal JH, Deutsch DN, Charney DS: The biological basis of panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 10):23–31Google Scholar

3. Gorman JM, Goetz RR, Fyer M, King DL, Fyer AJ, Liebowitz M, Klein DF: The mitral valve prolapse-panic disorder connection. Psychosom Med 1988; 50:114–122Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Bulbena A, Duró JC, Porta M, Martín-Santos R, Mateo A, Molina L, Vallescar R, Vallejo J: Anxiety disorder in the joint hypermobility syndrome. Psychiatry Res 1993; 43:59–68Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Devereux RB: Recent developments in the diagnosis and management of mitral valve prolapse. Curr Opin Cardiol 1995; 10:107–116Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Alpert MA, Sabeti M, Kushner MG, Beitman BD, Russell JL, Thiele JR, Mujerji V: Frequency of isolated panic attacks and panic disorder in patients with the mitral valve prolapse syndrome. Am J Cardiol 1992; 69:1489–1490Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Sivaramakrishnan K, Alexander PJ, Saharsarnaman N: Prevalence of panic disorder in mitral valve prolapse: a comparative study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 89:59–61Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Schutte JE, Gaffney FA, Blend L, Blomqvist CG: Distinctive anthropometric characteristics of women with mitral valve prolapse. Am J Med 1981; 71:533–538Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Devereux RB, Kramer-Fox R: Inheritance and phenotypic features of prolapse and the mitral valve prolapse syndrome, in Mitral Valve Prolapse and the Mitral Valve Prolapse Syndrome. Edited by Boudoulas H, Wooley CF. Mount Kisco, NY, Futura, 1988, pp 109–128Google Scholar

10. Bulbena A, Martín-Santos R, Porta M, Duró JC, Gago J, Sangorrín J, Gratacós M: Somatotype in panic patients. Anxiety 1996; 2:80–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Savage D, Garrison RJ, Devereux RB, Castelli WP, Anderson SJ, Levy D, McNamara PM, Stokes J, Kannel WB, Feinleib M: Mitral valve prolapse in the general population, I: Epidemiologic features—the Framingham Study. Am Heart J 1983; 106:571–575Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Weissman M: The epidemiology of anxiety disorders: rates, risks and familial patterns. J Psychiatr Res 1988; 22:29–114Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Katerndahl DA: Panic and prolapse: meta-analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis 1993; 181:539–544Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Rotés J, Argany A: La laxité articulaire considerée comme facteur des altérations de l'appareil locomoteur. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic 1957; 24:535–539Medline, Google Scholar

15. Beighton PH, Solomon L, Soskolne CL: Articular mobility in an African population. Ann Rheum Dis 1973; 32:413–418Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Beighton PH, Grahame R, Bird H: Hypermobility of Joints, 2nd ed. London, Springer-Verlag, 1989Google Scholar

17. Grahame R, Edwards JC, Pitcher D, Gabell A, Harvey W: A clinical and echocardiographic study of patients with hypermobility syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 1981; 40:541–546Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Pitcher D, Grahame R: Mitral valve prolapse and joint hypermobility: evidence for a systemic connective tissue abnormality? Ann Rheum Dis 1982; 41:352–354Google Scholar

19. Child A: Joint hypermobility syndrome: inherited disorder of collagen synthesis. J Rheumatol 1986; 13:239–243Medline, Google Scholar

20. Lewkonia RM: The biology and clinical consequences of articular hypermobility. J Rheumatol 1993; 20:220–222Medline, Google Scholar

21. Tamura K, Fakuda Y, Yamanka N, Ferrans VJ: Structural abnormalities of connective tissue in floppy mitral valve (abstract). J Am Coll Cardiol 1994; 23:32AGoogle Scholar

22. Morgan AW, Grahame R: Special interest group report: Special Interest Group for Joint Hypermobility, April 1995, Glasgow. Br J Rheumatol 1996; 35:392–393Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Bulbena A, Duro JC, Porta M, Vallejo J: Anxiety disorders in the joint hypermobility syndrome Lancet 1988; 2:694Google Scholar

24. Schlesslman JJ, Stolley PD: Case-Control Studies: Design, Conduct, Analysis. New York, Oxford University Press, 1982Google Scholar

25. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: User’s Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

26. González de Rivera JL, Morera A: Reactividad al estrés en pacientes ingresados en un hospital general. Actas Luso Esp Neurol Psiquiatr 1984; 12:207–213Google Scholar

27. Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG: Manual of Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. London, Hodder and Stoughton, 1975Google Scholar

28. Hamilton M: The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1959; 32:50–55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Bulbena A, Duró JC, Porta M, Faus S, Vallescar R, Martín-Santos R: Clinical assessment of hypermobility of joints: assembling criteria. J Rheumatol 1992; 19:115–122Medline, Google Scholar

31. Alpert MA, Carney RJ, Flaker GC, Sanfelippo JF, Webel RR, Kelly DL: Sensitivity and specificity of two-dimension echocardiographic signs of mitral valve prolapse. Am J Cardiol 1984; 54:792–796Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Devereux RB, Kramer-Fox R, Shear MK, Kligfield P, Pini R, Savage DD: Diagnosis and classification of severity of mitral valve prolapse: methodologic, biologic, and prognostic considerations. Am Heart J 1987; 113:1265–1280Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Armitage P, Berry G: Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 3rd ed. Oxford, Blackwell, 1994Google Scholar

34. Siegel S, Castellan NJ Jr: Nonparametric Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1988Google Scholar

35. Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Mogenstern H: Epidemiologic Research: Principles and Quantitative Methods. Belmont, Calif, Lifetime Learning Publications, 1982Google Scholar

36. Liberthson R, Sheehan DV, King ME, Weyman AE: The prevalence of mitral valve prolapse in patients with panic disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:511–515Link, Google Scholar

37. Coplan JD, Andrews MW, Rosenblum LA, Owens MJ, Friedman S, Gorman JM, Nemeroff CB: Persistent elevations of cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of corticotropin-releasing factor in adult nonhuman primates exposed to early-life stressors: implications for the pathophysiology of mood and anxiety disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93:1619–1623Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Battaglia M, Bertella S, Politi E, Bernardeschi L, Perna G, Gabriele A, Bellodi L: Age at onset of panic disorder: influence of familial liability to the disease and of childhood separation anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1362–1364Link, Google Scholar

39. Brown DR: Exercise, fitness and mental health, in Exercise, Fitness and Health. Edited by Bouchard C, Shephard RJ, Stephens T, Sutton JR, McPherson BD. Champaign, Ill, Human Kinetics, 1988, pp 607–626Google Scholar

40. Feinstein AR: Clinical Epidemiology: The Architecture of Clinical Research. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1985Google Scholar