Firearm-Related Suicide Among Young African-American Males

Abstract

National trends in firearm-related suicides among African-American and white males in the age groups 15 to 19 years and 20 to 24 years from 1979 to 1997 were examined. The rates and percentages of suicide by firearms increased significantly more among African-American males than among white males. During the 19-year period, firearms accounted for about 70 percent and 64 percent of all suicides among males aged 15 to 19 years and 20 to 24 years, respectively. The results support the Surgeon General's 1999 call for greater awareness of the suicide risk among African-American males.

In 1999 Surgeon General David Satcher (1) described the increasing rate of suicide among young African-American males and other nonwhite ethnic groups as an emerging public health problem. Suicide accounts for 12 percent of all deaths among adolescents and young adults and is the third leading cause of death among African-American males aged 15 to 24 years (2). In 1998 a total of 3,532 males in this age group committed suicide, equivalent to a rate of 18.5 per 100,000 population (2). Reports show that the historical gap in suicide rates between African-American males and white males of similar age has been narrowing (3). Although the suicidal behavior of young African-American males seems to be gaining the attention of the public health community, little knowledge has accrued about the pattern of and trends in firearm-related suicide in this group.

Several scholars have examined the rate of suicide among African Americans (3,4,5). However, no recent study has had sufficient demographic specificity in its analysis of the upward trend in firearm-related suicides among younger African-American males. Here we update the literature with an analysis of data on long-term trends in firearm-related suicide among African-American and white males in the age groups 15 to 19 years and 20 to 24 years from 1979 to 1997. Annual time-series data were analyzed to examine differences in age-specific trends in and patterns of firearm-related suicide between African-American and white males in these two age groups. We examine the results in the context of the Surgeon General's "Call to Action to Prevent Suicide" (1).

Methods

Suicide data were obtained from the compressed mortality files from the Office of Analysis and Epidemiology at the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for the period 1979 to 1997 and were downloaded by using the Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER). The data from the compressed mortality files, derived from death certificate files submitted by each state, are coded by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and are available by race—white, black, or other. We selected male decedents between the ages of 15 and 24 years to identify those who had committed suicide with a firearm (ICD codes E955.0 to E955.4) and those who had committed suicide by using other means (codes E950.0 to E954 and E955.5 to E959.9).

To examine the magnitude and statistical significance of changes in firearm-related suicide rates from 1979 to 1997, we performed linear and quadratic analyses separately for each rate to estimate change expressed as an increase or decrease in the rate per 100,000 population. Analysis of covariance was used to compare trends in firearm-related suicide rates between African-American and white males. We used the chi square test for trends to determine whether the percentage of suicides by firearms increased or decreased linearly.

Results

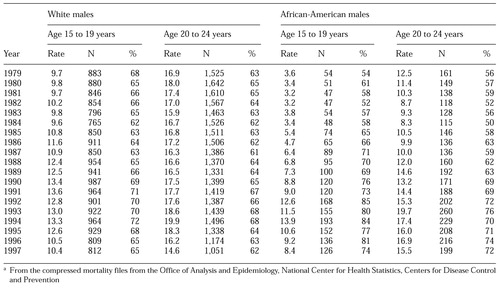

The data provided further evidence of the narrowing gap between African-American and white male suicide. During the period 1979 to 1997, the rate of suicide among African-American males aged 15 to 24 years increased by 14 percent, from 14 per 100,000 to 16 per 100,000, while the rate among white males in the same age group decreased by 4.9 percent, from 20.5 per 100,000 to 19.5 per 100,000. During the 19-year period, 7,678 suicide deaths among African-American males were caused by firearms, compared with 67,619 among white males. The rates for individual years are listed in Table 1. Firearms were used in nearly three of every four suicides across the four race and age groups. The rate of suicide by firearms in the four groups combined peaked in 1994 at 9.4 per 100,000.

A stratified analysis showed that the rate of firearm-related suicides among African-American males aged 15 to 19 years increased by 133 percent between 1979 and 1997, from 3.6 per 100,000 to 8.4 per 100,000 (beta=.57, df=17, p<.001). Among African-American males aged 20 to 24 years, the rate increased by 24 percent, from 12.5 per 100,000 to 15.5 per 100,000 (beta=.47, df=17, p<.001). In contrast, the rate for white males in the 15- to 19-year age group increased by only 7 percent, from 9.7 per 100,000 to 10.4 per 100,000 (beta=.16, df=17, p<.01), and the rate for white males in the 20- to 24-year age group did not vary significantly over time. The rate of increase was significantly greater for African-American males than for white males in the 15- to 19-year age group (t=5.38, df=1, p< .001). Further analysis showed that from 1985 to 1994 the rate of firearm-related suicide increased precipitously among males 15 to 19 years old and then declined notably in later years for both African-American males (beta=−.01, df=16, p<.001) and white males (beta=−.03, df=16, p<.001).

The number of suicides involving firearms expressed as a percentage of all suicides increased precipitously among African-American males after declining slightly in the early 1980s and had surpassed that for white males in the same age categories by 1986. The largest increase over the study period was seen among African-American males in the 15- to 19-year age group (χ2=14.4, df=1, p=.001). Between 1994 and 1997, of the four groups examined, African-American males aged 20 to 24 years showed an increase in the percentage of firearm-related suicides (χ2=14.23, df=1, p=.001), whereas decreases were observed for the other groups.

For cases in which the type of firearm was specified, handguns (ICD code 955.0) were the predominant type used by African-American males to commit suicide (59 percent), whereas white males (43 percent) predominantly used shotguns (code 955.1). The type of firearm involved in the suicide was more likely to be unspecified (ICD code 955.4) for African-American males (75 percent) than for white males (56 percent).

Discussion and conclusions

Overall, firearms were involved in about 63 percent of all suicides among African-American and white males from 1979 to 1997. Significant differences appeared over time in the rate of firearm-related suicide and in the type of firearm used across the four race and age groups. The proportion of suicides that involved firearms increased at a greater rate among African-American males than among white males. As a result of this increase, the gap between suicide rates for African-American and white males narrowed.

The results of this study must be interpreted with caution, because, as has been shown in other research, data based on death certificates are likely to underreport suicide rates among African Americans (6). However, data on firearm-related suicides might involve less underreporting than data on suicide by other means (7). The evidence is clear that firearm-related suicide is becoming a major public health problem among young African-American males.

The 1999 Surgeon General's report on suicide (1) highlights the importance of restricting access to firearms in preventing suicide (2,8). Our findings underscore the need for all health care professionals to regularly ask whether depressed or suicidal African-American youths have access to firearms. Although this recommendation may seem obvious, several studies of medical practitioners have found that such patients are not asked this question with any kind of regularity (9,10).

We found that among male firearm-related suicides for which the type of firearm was known, handguns were the most common type used to commit suicide. Thus interventions that are designed to limit the availability of handguns and that include training for caregivers and community helpers may be appropriate mechanisms for reducing the risk of suicide by firearms among young African-American males.

Beyond the clinical implications of these results, future research is needed to improve our understanding of the impact of social exclusion, economic deprivation, and substance abuse on suicidal behavior among young African-American males. Also, much remains to be learned about the role of the availability of firearms in the increase in the proportion of firearm-related suicides in this population. Finally, our findings support the Surgeon General's call for greater awareness of the suicide risk among African-American males and the fact that these deaths are preventable, especially if we address access to firearms in this demographic group.

Dr. Joe is affiliated with the Center for Intervention and Practice Research in the School of Social Work at the University of Pennsylvania, 4200 Pine Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Kaplan is with the School of Community Health at Portland State University in Portland, Oregon.

|

Table 1. Firearm-related suicides among African-American and white males aged 15 to 24 years from 1979 to 1997, expressed as deaths per 100,000 (rate), number of suicides that involved firearms, and percentage of all suicidesa

a From the compressed mortality files from the Office of Analysis and Epidemiology, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

1. The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent Suicide, 1999. Washington, DC, US Public Health Service, 2000Google Scholar

2. Murphy SL: Deaths: Final Data for 1998: National Vital Statistics Reports 48, no 11. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, 2000Google Scholar

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Suicide among African-American youths: United States, 1980-1995. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports 47:193-196, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

4. Gibbs JT: African-American suicide: a cultural paradox. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 27:68-79, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

5. Kaplan MS, Geling O: Firearm suicides and homicides in the United States: regional variations and patterns of gun ownership. Social Science and Medicine 46:1227-1233, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Phillips DP, Ruth TE: Adequacy of official suicide statistics for scientific research and public policy. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 23:307-319, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

7. Boyd JH, Moscicki EK: Firearm and youth suicide. American Journal of Public Health 76:1240-1242, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Ludwig J, Cook PJ: Homicide and suicide rates associated with implementation of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act. JAMA 284:585-591, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. McManus BL, Kruesi MJ, Dontes AE, et al: Child and adolescent suicide attempts: an opportunity for emergency departments to provide injury prevention education. American Journal of Emergency Medicine 15:357-360, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Kaplan MS, Adamek ME, Rhoades JA: Prevention of elderly suicide: physicians assessment of firearm availability. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 15(1):60-64, 1998Google Scholar