Thinking About Schizophrenia in an Era of Genomic Medicine

Abstract

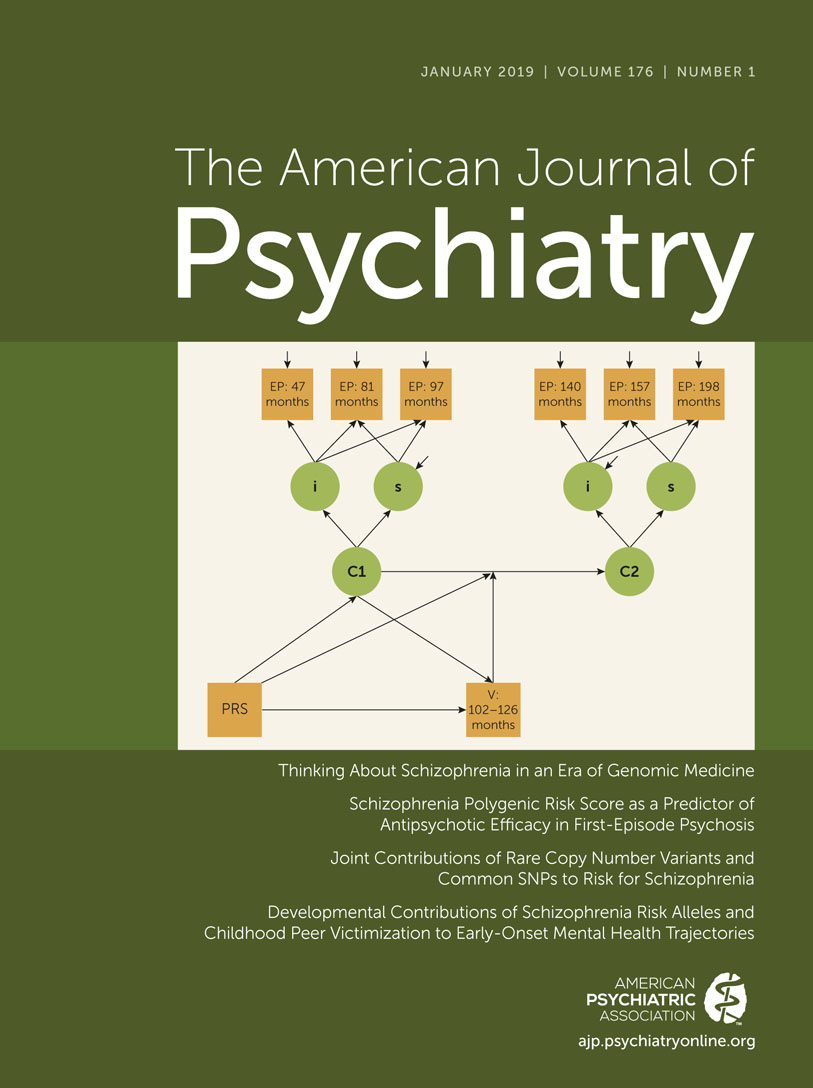

Genetic discoveries about human brain development and neuropsychiatric syndromes have changed the landscape of psychiatric research. The genotyping of hundreds of thousands of individuals has identified many hundreds of genomic regions that are associated with psychiatric diagnoses, and progress is being made in uncovering the specific genes that underlie these statistical associations, although most are still undetermined. While there are great expectations that such genetic discoveries will lead to novel treatments based on fundamental mechanisms of illness, there are important caveats. Individual risk-associated common variants explain only a tiny fraction of individual liability. The degree to which common risk variants represent “core” pathogenic insights is controversial. Individuals with rare and more penetrant risk variants are often intellectually disabled, which raises epistemological questions about classification. In clinical research, the application of polygenic risk scores—the cumulative sum of associated alleles in an individual genome—to prediction models of environmental influences and outcome is gaining enthusiasm because these scores explain more liability, but predictions are small and not yet actionable for individuals. Psychiatry is intertwined with genomic medicine, and our understanding of what we call schizophrenia and the possibilities of improving the lives of affected individuals have never seemed more promising. Yet the research challenges are daunting; psychiatric syndromes ultimately reflect how the brain mishandles environmental information, which at the systems level is far “downstream” of the effect of genes in cells.