Hurtful Words: Association of Exposure to Peer Verbal Abuse With Elevated Psychiatric Symptom Scores and Corpus Callosum Abnormalities

Abstract

Objective:

Previous studies have shown that exposure to parental verbal abuse in childhood is associated with higher rates of adult psychopathology and alterations in brain structure. In this study the authors sought to examine the symptomatic and neuroanatomic effects, in young adulthood, of exposure to peer verbal abuse during childhood.

Method:

A total of 848 young adults (ages 18–25 years) with no history of exposure to domestic violence, sexual abuse, or parental physical abuse rated their childhood exposure to parental and peer verbal abuse and completed a self-report packet that included the Kellner Symptom Questionnaire, the Limbic Symptom Checklist–33, and the Dissociative Experiences Scale. Diffusion tensor images were collected for a subset of 63 young adults with no history of abuse or exposure to parental verbal abuse selected for varying degrees of exposure to peer verbal abuse. Images were analyzed using tract-based spatial statistics.

Results:

Analysis of covariance revealed dose-dependent effects of peer verbal abuse on anxiety, depression, anger-hostility, dissociation, “limbic irritability,” and drug use. Peer and parental verbal abuse were essentially equivalent in effect size on these ratings. Path analysis indicated that peer verbal abuse during the middle school years had the most significant effect on symptom scores. Degree of exposure to peer verbal abuse correlated with increased mean and radial diffusivity and decreased fractional anisotropy in the corpus callosum and the corona radiata.

Conclusions:

These findings parallel results of previous reports of psychopathology associated with childhood exposure to parental verbal abuse and support the hypothesis that exposure to peer verbal abuse is an aversive stimulus associated with greater symptom ratings and meaningful alterations in brain structure.

Exposure to trauma in childhood is associated with elevated vulnerability to psychiatric disorders (1–3). This has been shown to be true in early childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse, and witnessing of domestic violence as well as in composite scores reflecting exposure to multiple forms of trauma (4). We previously reported that parental verbal abuse is an important but often overlooked form of childhood adversity that is more strongly associated with symptom ratings (such as depression and anger-hostility) than is parental physical abuse (5, 6).

Exposure to physical and verbal aggression from peers, perpetrated by other children who are not siblings and are not necessarily age-mates, is also a highly prevalent form of childhood stress (7). It may occur in the form of physical blows, verbal taunts, or social ostracism.

Victims of peer aggression show the scars. They have increased rates of depression, suicidal ideation, loneliness, and even psychosis (7–9); their grades are lower and their absentee rates higher (10); they are more likely to carry weapons to school and to engage in fights (11); they are likely to suffer more injuries, abuse over-the-counter medications, intentionally hurt animals and other people, and use weapons that could seriously harm others (10).

In this study, we sought to ascertain what the effects of exposure to peer verbal abuse are in young adulthood. We asked whether childhood exposure to peer verbal abuse in the absence of physical bullying was associated with elevations in psychiatric symptoms, similar to the effects we observed with childhood exposure to parental verbal abuse. We also examined diffusion tensor imaging scans from a group of healthy volunteers to ascertain whether the integrity of white matter tracts might be affected by exposure to peer verbal abuse, as we had recently observed in individuals exposed to parental verbal abuse (12).

Method

Participants

Detailed ratings of symptoms and exposure to emotional abuse and trauma were collected and analyzed from our multistudy community database of 1,662 young adults (636 male and 1,026 female) 18–25 years of age who responded to an advertisement entitled “Memories of Childhood.” All participants gave informed consent prior to participation. We focused on a group of 848 participants (363 male and 485 female, with a mean age of 21.8 years [SD=2.1]) who had no exposure to domestic violence, childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, or peer physical bullying and a subset of 707 participants (298 male and 409 female, with a mean age of 21.9 years [SD=2.1]) who in addition had no exposure to either maternal or paternal verbal abuse; exposure to verbal abuse was defined as a maternal or paternal score ≥40 on the Verbal Abuse Questionnaire (5).

Diffusion tensor imaging was performed on a subset of 63 participants (23 male and 40 female, with a mean age of 21.9 years [SD=1.9]) who had no history of exposure to childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse, witnessing domestic violence, peer physical bullying, harsh corporal punishment, or significant parental verbal abuse and no history of axis I or II psychiatric disorders; all were recruited as healthy comparison subjects for other studies. These participants did, however, differ in their degree of exposure to peer verbal abuse.

Assessments

Abuse and trauma ratings.

History of exposure to trauma was obtained using previously described methods (5) for the evaluation of physical abuse and childhood sexual abuse. History of witnessing domestic violence was assessed using the questions “Have you ever witnessed serious domestic violence?” “Have you heard domestic violence in your family?” “Have you watched your mother (father) threatened or assaulted?” and “Have you heard your mother (father) threatened or assaulted?” Ratings of exposure to parental or peer verbal abuse were assessed using the Verbal Abuse Questionnaire, which consists of 15 items that cover the key components of verbal abuse—scolding, yelling, swearing, blaming, insulting, threatening, demeaning, ridiculing, criticizing, screaming, belittling, and so on. In a preliminary sample of 48 college students, the Verbal Abuse Questionnaire showed high internal consistency as applied to reports of both maternal behaviors (Cronbach alpha=0.98) and paternal behaviors (Cronbach alpha=0.94). In the present sample, the Verbal Abuse Questionnaire also showed high internal consistency for female (Cronbach alpha=0.95) and male peer verbal abuse (Cronbach alpha=0.96).

Symptom ratings.

As in our previous studies of participants exposed to verbal abuse (5, 6, 12), self-report ratings were obtained using Kellner's Symptom Questionnaire (13), the Dissociative Experiences Scale (14), and the Limbic System Checklist–33 (15). The Kellner Symptom Questionnaire provides four symptom scales (depression, anxiety, anger-hostility, and somatic complaints). Depression and anxiety scores ≥12 are considered clinically significant (5, 13). Dissociative Experiences Scale scores >30 are considered clinically significant and warrant further investigation (16). The Limbic System Checklist–33 evaluates the frequency with which participants experience symptoms often encountered as ictal temporal lobe epilepsy phenomena (17). In our clinical experience, scores ≥40 are often associated with EEG abnormalities (spikes, sharp waves, paroxysmal slowing).

Demographic characteristics.

Data on race, ethnicity, education, parental education, family income, and perceived financial sufficiency during childhood (1=much less than enough money to meet our needs, 5=much more than enough money to meet our needs) were collected. We included perceived financial sufficiency as an alternative to family income, as participants were often uncertain of their parents' income, and family income could mean very different things depending on locale, family size, and parental spending habits. In all cases, perceived financial sufficiency explained a greater share of the variance in symptom ratings than combined family income.

Image Acquisition

MRI scanning was conducted at McLean Hospital's Brain Imaging Center. Heads were stabilized with cushions and tape to help minimize movement. Multiple diffusion-weighted images, with 12 encoding directions and an additional T2-weighted scan, were acquired using a 3-T Siemens Trio scanner (Siemens, Iselin, N.J.) with standard single-shot, spin echo, echo planar acquisition sequence with eddy current balanced diffusion weighting gradient pulses to reduce distortion (18). Scan parameters were gradient factor=1,000 seconds/mm2, echo time=81 msec, repetition time=5 sec; matrix=128×128 on a 220 mm×220 mm field of view; slices were 5 mm without gap, resulting in voxels of 1.71875 mm×1.71875 mm×5 mm. Four magnitude averages provided sufficient signal-to-noise ratios. Volumetric T1-weighted anatomic reference images were acquired using a magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo sequence (echo time=2.74 msec, repetition time=2.1 seconds, inversion time=1 second; 256×256×128 matrix for 1×1×1.3 mm voxels).

Data Analysis

Effects of exposure to peer verbal abuse were assessed in the participants who had no exposure to childhood sexual abuse, witnessing of domestic violence, parental physical abuse, or parental verbal abuse (N=707). The maximal degree of exposure to male or female peer verbal abuse (that is, whichever score was greater on the Verbal Abuse Questionnaire) was binned into deciles (0–9, 10–19, … 50+) and assessed using analysis of covariance. Parental education and perceived financial sufficiency were included as covariates (19). Structural equation modeling (SEM in the R software package; www.r-project.org) was used to perform simple path analyses to determine whether peer verbal abuse had different consequences depending on developmental stage (20). For these analyses, we calculated the degree of exposure to male or female peer verbal abuse during elementary, middle, and high school years based on maximal degree of exposure during each year and the number of years of occurrence, as measured by the Verbal Abuse Questionnaire.

The model also included parental education and perceived financial sufficiency as sociodemographic variables. Data were adjusted to control for gender differences in symptom ratings. Multiple regression analysis was used to ascertain the relative impact of exposure to peer versus parental verbal abuse in participants with no exposure to childhood sexual abuse, witnessing of domestic violence, or parental physical abuse (N=848). Gender, parental education, and perceived financial sufficiency were included as additional interest variables. This approach has the advantage of using exposure ratings as continuous variables without requiring cutoff scores to delineate significant degrees of exposure.

Image Analysis

Diffusion tensor imaging preprocessing, including exclusion of nonbrain tissue using the Brain Extraction Tool and correction for movement and eddy currents, was performed using the FMRIB Software Library (FSL; Oxford, England). A diffusion tensor model was fitted to each voxel to derive fractional anisotropy, mean diffusivity, axial diffusivity, and radial diffusivity images.

The tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) tool in FSL was used to calculate tract-based differences in fractional anisotropy and diffusivity. TBSS is a new approach that uses an anatomically based, carefully tuned, nonlinear registration procedure to project results onto an alignment-invariant tract representation (the “mean fractional anisotropy skeleton”) for voxelwise analysis of multisubject diffusion data. TBSS computes a group mean fractional anisotropy skeleton, which represents the centers of all fiber bundles that are common to the participants involved in the study (21). Each participant's aligned fractional anisotropy image was projected onto the skeleton, and the resulting data were fed into voxelwise statistics. Multiple regression analyses were performed to identify clusters within fiber tracts whose fractional anisotropy, mean diffusivity, axial diffusivity, or radial diffusivity values correlated with severity of exposure to peer verbal abuse. This analysis was adjusted for effects of gender and age. Tracts were identified in which the significance of the correlation was p<0.05 after correction for multiple comparisons using threshold-free cluster enhancement (21).

Results

Degree of Exposure and Effects of Peer Verbal Abuse

This analysis was conducted on data from participants with no history of physical abuse or parental verbal abuse (N=707). Participants differed widely in their degree of exposure to peer verbal abuse, as measured on the Verbal Abuse Questionnaire. Males reported a greater degree of exposure to male than female peer verbal abuse (male peer verbal abuse score=24.4 [SD=19.3]; female peer verbal abuse score=14.7 [SD=16.2]; tdep=11.29, df=290, p<10−24), whereas females reported the opposite pattern (male peer verbal abuse score=9.4 [SD=12.5]; female peer verbal abuse score=13.0 [SD=13.6]; tdep=−7.09, df=402, p<10−11). Within-subject ratings of exposure to male compared with female peer verbal abuse were well correlated (r=0.639), indicating that individuals exposed to verbal abuse by peers of one gender were often exposed to verbal abuse by peers of the other gender. Maximal degree of exposure to either male or female peer verbal abuse was used as an overall exposure index. Males, on average, reported a substantially greater degree of exposure to peer verbal abuse than females (males: score=25.8 [SD=19.6]; females: score=14.6 [SD=14.4]; F=76.80, df=1, 705, p<10−16).

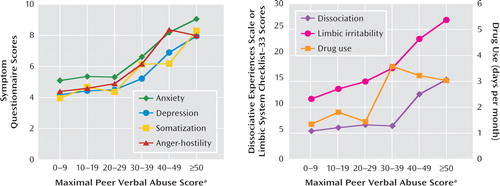

The dose-dependent relationship between degree of exposure to peer verbal abuse and symptom ratings is illustrated in Figure 1. There were strong main effects of peer verbal abuse exposure scores on all ratings. The weakest association was with degree of drug use (F=4.82, df=5, 685, p<0.0003), and the strongest was with ratings of “limbic irritability” (F=18.66, df=5, 682, p<10−16). The remaining ratings were affected to similar degrees, ranging from depression (F=5.60, df=5, 658, p<10−4) to dissociation (F=14.73, df=5, 660, p<10−12). For Kellner Symptom Questionnaire ratings and degree of drug use, there appeared to be an inflection point with peer Verbal Abuse Questionnaire exposure scores ≥30 resulting in significantly higher ratings than scores <30. Dissociative Experiences Scale scores had an inflection point at scores ≥40. Limbic System Checklist–33 scores, in contrast, showed a more consistently graded response. We defined peer verbal abuse scores ≥30 to be indicative of significant exposure and peer verbal abuse scores ≥40 as substantial exposure.

FIGURE 1. Effect of Exposure to Peer Verbal Aggression on Symptoms in 707 Young Adults With No History of Physical or Sexual Abuse or Parental Verbal Abusea

a Participants had no exposure to childhood sexual abuse, witnessing of domestic violence, parental or peer physical abuse, or parental verbal abuse. Maximal peer verbal abuse score refers to the maximal score of male or female peers on the Verbal Abuse Questionnaire. Symptoms were assessed with the Kellner Symptom Questionnaire, the Limbic System Checklist–33, the Dissociative Experiences Scale, and days per month of drug use.

Substantial exposure to peer verbal abuse was associated with an elevated risk for clinically significant symptom ratings. Odds ratios were 2.3 (95% CI=1.1–4.8) for depression, 3.7 (95% CI=1.8–7.5) for anxiety, 4.5 (95% CI=1.6–12.1) for “limbic irritability,” and 10.5 (95% CI=2.1–51.4) for dissociation.

Males and females appeared to be similarly affected by exposure to peer verbal abuse on most measures. However, there were significant gender-by-peer verbal abuse interactions on ratings of dissociation (F=4.01, df=5, 673, p<0.001), “limbic irritability” (F=3.56, df=5, 695, p<0.004), and drug use (F=4.89, df=5, 698, p=0.0002). Exposure to peer verbal abuse was associated with a greater increase in Dissociative Experiences Scale and Limbic System Check-list–33 scores in females than in males. Conversely, males were more sensitive to peer verbal abuse in degree of drug use, with increased use in males emerging at lower levels of peer verbal abuse than in females.

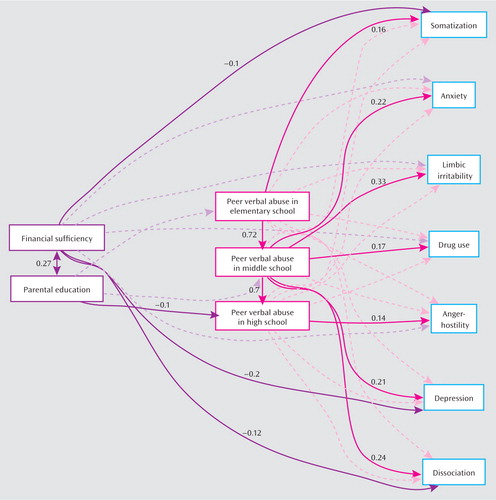

Path analysis indicated that there was a significant relationship between ages of exposure to peer verbal abuse and symptom ratings (Figure 2). The model was well fitted (adjusted goodness-of-fit index=0.989, Bentler-Bonnett normed fit index=0.984, Tucker-Lewis non-normed fit index=1.00) and could not be rejected by chi-square criteria (χ2=40.88, df=39, p=0.82). Ratings on most of the symptom scales were associated with degree of exposure to peer verbal abuse during middle school. This was true for dissociation (p<0.003), depression (p=0.01), anxiety (p<0.007), drug use (p<0.04), and “limbic irritability” (p<0.0001). Ratings of somatization were associated with degree of peer verbal abuse during elementary school (p<0.02), while anger-hostility was significantly associated with peer verbal abuse during high school (p<0.04). Path analysis indicated that parental education influenced the amount of exposure to peer verbal abuse during high school (p<0.05). Perceived financial sufficiency did not directly influence degree of exposure, but low levels increased ratings of dissociation (p<0.02), depression (p<0.0001), and somatization (p<0.05).

FIGURE 2. Path Analysis Modeling the Relationship Between Exposure to Peer Verbal Abuse, by Educational Stages, Perceived Financial Sufficiency During Childhood, and Parental Education Levels and Symptom Ratings in 707 Young Adultsa

a Significant associations and standard weights are shown by solid lines and values. Nonsignificant associations included in the model are illustrated by dotted lines. The sample consists of participants with no exposure to childhood sexual abuse, witnessing of domestic violence, parental or peer physical abuse, or parental verbal abuse.

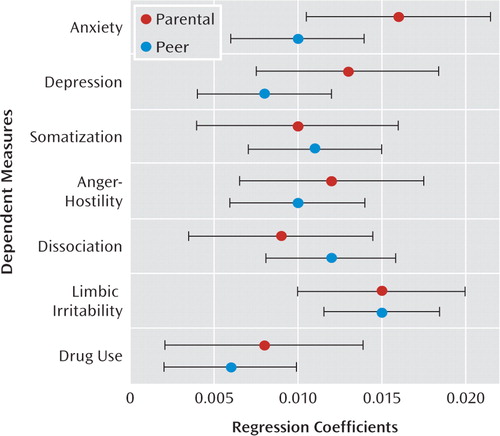

Peer Versus Parental Verbal Abuse

This analysis was conducted on data from participants with no history of abuse (N=848). Figure 3 illustrates the least squares multiple regression coefficients predicting symptom scores by both parental and peer verbal abuse exposure. All of the regression coefficients were significantly greater than zero. There was substantial overlap between the 95% confidence intervals for parental and peer regression coefficients across all measures, indicating that within each measure there were no significant differences between these two forms of verbal abuse in effect size. Only 2% of this sample was exposed to high levels of both peer and parental verbal abuse.

FIGURE 3. Effect of Exposure to Parental Verbal Abuse and Peer Verbal Abuse on Symptom Ratings and Drug Use in 848 Young Adultsa

a Regression coefficients for the multiple regression equation are shown; tic marks indicate 95% confidence intervals. Ratings on the dependent measures were standardized (mean=0, SD=1) so that the relative impact of peer and parental verbal abuse could be compared regardless of the scoring range and scaling of the different rating instruments. Under these circumstances, a regression coefficient of 0.01 indicated that a 50-point increase in Verbal Abuse Questionnaire score was associated with a 0.5 standard deviation increase in rating score.

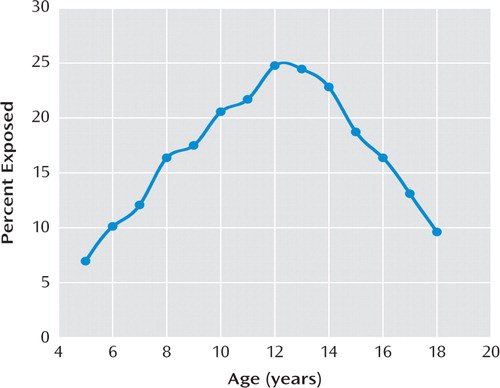

Incidence and Timing of Exposure

This analysis was conducted with data from the community sample (N=1,662). Figure 4 provides information on the frequency of exposure to significant levels of peer verbal abuse across age. Exposure peaked during the middle school years (grades 6–8, typically ages 11–14). Children exposed to peer verbal abuse during elementary school often had this exposure persist into middle school. However, 9.8% of participants in the community sample were exposed to significant levels of peer verbal abuse during middle school but not elementary school.

FIGURE 4. Percentage of 1,662 Young Adults in a Community Sample Reporting Exposure to Significant Peer Verbal Abuse Between Ages 5 and 18a

a Significant peer verbal abuse was defined as maximal peer Verbal Abuse Questionnaire scores ≥30). Note that exposure peaks at ages 12–13.

Neuroimaging Sample (N=63)

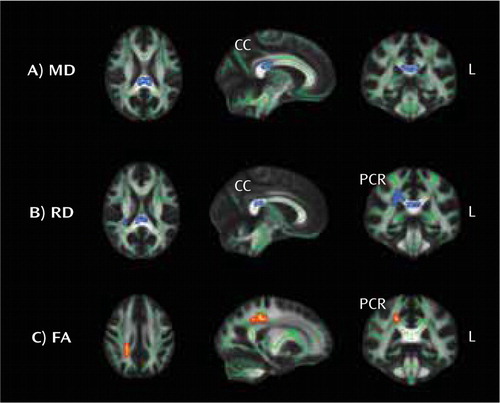

As shown in Figure 5, there was a significant correlation between degree of exposure to peer verbal abuse and mean diffusivity in the splenium of the corpus callosum (Montreal Neurological Institute [MNI] coordinates: −7, −31, 22; p<0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons). Mean diffusivity in this cluster correlated with levels of female peer verbal abuse (r=0.617) and male peer verbal abuse (r=0.723). The correlation between degree of exposure to peer verbal abuse and measures of mean diffusivity were similar in males and females (males: r=0.647, females: r=0.810; z=−1.26, p>0.2). In this sample (selected to be free of axis I and II disorders), the only noteworthy clinical correlation was between maximal peer verbal abuse scores and ratings of anxiety (r=0.33, p=0.01).

FIGURE 5. Regions in the Corpus Callosum (CC) and Posterior Corona Radiata (PCR) in Which Correlations Were Observed Between Degree of Exposure to Peer Verbal Abuse and Mean Diffusivity (MD), Radial Diffusivity (RD), and Fractional Anisotropy (FA)a

a Regions were identified with diffusion tensor imaging and the tract-based spatial statistics tool in FSL. Blue coloring indicates a positive correlation with diffusion measurements. Red coloring indicates an inverse correlation with measures of fractional anisotropy. The sample consists of 63 participants who had no exposure to childhood sexual abuse, witnessing of domestic violence, parental or peer physical abuse, or parental verbal abuse and were free of axis I and II disorders.

Analysis of radial diffusivity also showed a significant positive correlation with exposure to peer verbal abuse in the body and splenium of the corpus callosum (MNI coordinates: 4, −30, 22 and −5, −34, 20; p<0.05) and the adjacent right posterior corona radiata (MNI coordinates: 28, −40, 22; p<0.05). Fractional anisotropy values showed a negative correlation with peer verbal abuse in an overlapping portion of the right posterior corona radiata (MNI coordinates: 28, −40, 22), although this correlation fell short of significance after correction for multiple comparisons (p=0.07). No positive or negative associations were detected between peer verbal abuse and axial diffusivity.

Discussion

Studying a community sample of young adults, we found that exposure to peer verbal abuse was associated with increased drug use and elevated psychiatric symptom ratings. Substantial exposure was associated with a greater than twofold increase in clinically significant ratings of depression, a threefold to fourfold increase in anxiety and “limbic irritability,” and 10-fold increase in dissociation. This level of peer verbal abuse was reported by 9.2% of participants who had no exposure to childhood sexual abuse, witnessing of domestic violence, or parental physical or verbal abuse and by 17.9% of the entire community sample. Hence, exposure to substantial levels of peer verbal abuse is a relatively common occurrence. Moreover, the effects of childhood exposure to peer verbal abuse on risk of psychopathology in early adulthood mirror results we previously reported for parental verbal abuse (5). Thus, verbal aggression from peers is an important and potent childhood stressor.

Middle school was the peak period of exposure to peer verbal abuse, with 9.8% of our community sample newly exposed. This finding fits with previous observations that peer physical aggression declines over the period from ages 8 to 18 while peer verbal abuse increases from ages 8 to 11, plateaus, and then declines from ages 15 to 18 (22, 23).

More importantly, the timing of exposure appears to shape its impact. Path analysis suggests that exposure during the middle school years (ages 11–14) was the most consequential and was associated with symptoms of anxiety, depression, dissociation, “limbic irritability,” and degree of drug use. Overall, there were no significant associations between these symptoms and degree of exposure during elementary or high school when degree of middle school exposure was excluded. However, exposure at early and later ages amplified the association between symptom ratings and middle school exposure, more than doubling the amount of variance explained. This suggests that exposure during elementary and high school may sensitize or reinforce the effects of exposure during middle school. These findings are consistent with previous reports indicating that exposure to peer verbal abuse in secondary school is more serious than peer verbal abuse during primary school (23, 24). This may be because children in primary school predominantly engage in dyadic relationships, which can attenuate the perceived impact of bullying outside the dyad (23).

Another perspective is also possible. We recently published data indicating that there are sensitive periods when brain regions are most susceptible to the effects of childhood sexual abuse (20). The hippocampus was most vulnerable to childhood sexual abuse occurring at ages 3–5 years and 11–13 years. It is possible that the hippo-campus is also susceptible to other forms of abuse occurring during these years. Anxiety, depression, dissociation, and temporal lobe epilepsy-like symptoms have all been associated with aspects of hippocampal function (12, 25–29). Hippocampal volume was not assessed in this study.

Diffusion tensor imaging, however, revealed an association between degree of exposure to peer verbal abuse and measures of mean diffusivity, radial diffusivity, and fractional anisotropy in the splenium of the corpus callosum and the overlying corona radiata. The corpus callosum is a massive fiber tract interconnecting the left and right hemispheres. The corona radiata contains both descending and ascending axons that carry nearly all of the neural traffic to and from the cerebral cortex. Many of these ax ons pass through the corpus callosum. Studies suggest that alterations in radial diffusivity but not axial diffusivity, as observed, result from effects on myelin rather than axon numbers (30, 31). Corpus callosum alterations appear to be the most consistent finding in maltreated children (32–34), and it is perhaps remarkable that they emerged in a sample of comparison subjects with no axis I or II disorders. The sensitive period for the splenium (the most caudal portion of the corpus callosum) likely occurs during the middle school years, given the rostral-caudal progression of corpus callosum myelination (35) and our finding that the rostral body of the corpus callosum had a sensitive period between ages 9 and 10 (20).

It is interesting to speculate on how white matter alterations in the splenium might be related to elevated risk for depression, dissociation, or substance abuse. Fibers passing through the splenium interconnect the right and left occipital and inferior temporal cortices. Together these regions comprise the ventral visual processing stream, which has reciprocal connections with the hippocampus. The visual cortex is a plastic structure that is extensively modified by early experience. We previously reported (36) that exposure to childhood sexual abuse was associated with a 12%–18% reduction in gray matter volume in the right and left primary and secondary visual cortex. We have also found similar alterations in witnessing domestic violence (unpublished data). While the visual cortex plays a critical role in sensory perception, it may have additional functions. A reproducible finding in major depression is a substantial reduction in occipital cortex g-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which is restored following treatment with antidepressants or ECT (37). Exposure to early stress may target GABA-ergic interneurons or fiber pathways of the visual cortex and increase risk for the development of mood disorders. We and others have also speculated that alterations in the corpus callosum may set the stage for dissociative phenomena by diminishing intrahemispheric integration (38). It is also possible that lack of integration between right and left hemispheric processing of visual cues may lead to greater cue-induced craving in substance users and enhanced risk for abuse and dependence.

This study is unique for a number of reasons. First, it assessed and controlled for exposure to other forms of mal-treatment, such as childhood sexual abuse and parental verbal abuse. Second, it focused entirely on peer verbal abuse as a specific form of childhood trauma distinct from peer abuse involving physical assaults. Third, effects of exposure during different developmental stages were assessed based on our finding of “sensitive periods” when brain regions are particularly susceptible to abuse.

However, we must acknowledge that these analyses are retrospective and correlative and hence are subject to problems associated with faulty recall and spurious association. It is possible that individuals who show a tendency toward psychopathology in childhood are targeted as “odd” by peers and subjected to verbal abuse (39). It is also conceivable that a preexisting abnormality in the corpus callosum enhances risk for psychopathology and peer abuse. Path analysis delineates a mathematical solution to a series of equations, not a causal pathway. Causality cannot be inferred from this retrospective experimental design. Prospective studies are needed to explore these possibilities.

Psychiatric disorders probably arise from the temporal intersection of genetic susceptibility and adverse early experiences during critical developmental stages (26). Theorists have often focused on the importance of very early experiences and parent-child interactions. This study and other recent reports (9, 40) should strengthen interest in the importance of peer interactions and the vulnerability of peripubertal children. These findings further enhance concern that exposure to ridicule, disdain, and humiliation from parents, partners, or peers is emotionally toxic and may adversely affect trajectories of brain development.

1. : Childhood abuse and lifetime psychopathology in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1878–1883Link, Google Scholar

2. : Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: an epidemiological and co-twin control analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000.; 57:953–959Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. : Childhood sexual abuse and mental health in adult life. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 163:721–732Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. : The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: a convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006; 256:174–186Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. : Sticks, stones, and hurtful words: relative effects of various forms of childhood maltreatment. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:993–1000Link, Google Scholar

6. : Cerebellar lingula size and experiential risk factors associated with high levels of alcohol and drug use in young adults. Cerebellum (Epub ahead of print, Oct 28, 2009).Google Scholar

7. : Twenty years' research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: a meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2000; 41:441–455Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. : Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA 2001; 285:2094–2100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. : Prospective study of peer victimization in childhood and psychotic symptoms in a nonclinical population at age 12 years. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009; 66:527–536Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. : Public health, safety, and educational risks associated with bullying behaviors in American adolescents. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2008; 20:223–233Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. : Relationships between bullying and violence among US youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2003; 157:348–353Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. : Preliminary evidence for white matter tract abnormalities in young adults exposed to parental verbal abuse. Biol Psychiatry 2009; 65:227–234Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. : A symptom questionnaire. J Clin Psychiatry 1987; 48:268–273Medline, Google Scholar

14. : Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986; 174:727–735Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. : Early childhood abuse and limbic system ratings in adult psychiatric outpatients. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1993; 5:301–306Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. : Frequency of dissociative disorders among psychiatric inpatients in a Turkish university clinic. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:800–805Abstract, Google Scholar

17. : Temporolimbic epilepsy and behavior, in Principles of Behavioral Neurology. Edited by Mesulam MM. Philadelphia, FA Davis, 1985, pp 289–326Google Scholar

18. : Reduction of eddy-current-induced distortion in diffusion MRI using a twice-refocused spin echo. Magn Reson Med 2003; 49:177–182Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. : Off with Hollingshead: socioeconomic resources, parenting, and child development, in Socioeconomic Status, Parenting, and Child Development. Edited by Bornstein MHBradley RH. Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2003, pp 83–106Google Scholar

20. : Preliminary evidence for sensitive periods in the effect of childhood sexual abuse on regional brain development. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2008; 20:292–301Link, Google Scholar

21. : Tract-based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage 2006; 31:1487–1505Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. : The development of direct and indirect aggressive strategies in males and females, in Of Mice and Women: Aspects of Female Aggression. Edited by Björkqvist KNiemelä P. San Diego, Calif, Academic Press, 1992, pp 51–64Google Scholar

23. : Lonely in the crowd: recollections of bullying. Br J Devel Psychol 2004; 22:379–394Crossref, Google Scholar

24. : A comparison of two approaches to the study of negative peer treatment: general victimization and bully/victim problems among German school children. Br J Devel Psychol 2002; 20:281–306Crossref, Google Scholar

25. : Anxiety is functionally segregated within the septo-hippocampal system. Brain Res 2004; 1001:60–71Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. : Stress, sensitive periods, and maturational events in adolescent depression. Trends Neurosci 2008; 31:183–191Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. : Hippocampal volume and depression: a meta-analysis of MRI studies. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1957–1966Link, Google Scholar

28. : Hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in dissociative identity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:630–636Link, Google Scholar

29. : MR detection of hippocampal disease in epilepsy: factors influencing T2 relaxation time. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1994; 15:1149–1156Medline, Google Scholar

30. : Dysmyelination revealed through MRI as increased radial (but unchanged axial) diffusion of water. Neuroimage 2002; 17:1429–1436Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. : Altered myelination and axonal integrity in adults with childhood lead exposure: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Neurotoxicology 2009; 30:867–875Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. : Developmental traumatology, part II: brain development. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45:1271–1284Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. : Childhood neglect is associated with reduced corpus callosum area. Biol Psychiatry 2004; 56:80–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. : Corpus callosum in maltreated children with posttraumatic stress disorder: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Psychiatry Res 2008; 162:256–261Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. : Diffusion tensor imaging: the normal evolution of ADC, RA, FA, and eigenvalues studied in multiple anatomical regions of the brain. Neuroradiology 2009; 51:253–263Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. : Childhood sexual abuse is associated with reduced gray matter volume in visual cortex of young women. Biol Psychiatry 2009; 66:642–648Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. : Increased cortical GABA concentrations in depressed patients receiving ECT. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:577–579Link, Google Scholar

38. : The neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2003; 27:33–44Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. : Childhood bullying behavior and later psychiatric hospital and psychopharmacologic treatment: findings from the Finnish 1981 birth cohort study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009; 66:1005–1012Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. : Victimization by peers and adolescent suicide in three US samples. J Pediatr 2009; 155:683–688Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar