Differentiating Early-Onset Persistent Versus Childhood-Limited Conduct Problem Youth

Abstract

Objective: Among young children who demonstrate high levels of conduct problems, less than 50% will continue to exhibit these problems into adolescence. Such developmental heterogeneity presents a serious challenge for intervention and diagnostic screening in early childhood. The purpose of the present study was to inform diagnostic screening and preventive intervention efforts by identifying youths whose conduct problems persist. The authors examined 1) the extent to which early-onset persistent versus childhood-limited trajectories can be identified from repeated assessments of childhood and early-adolescent conduct problems and 2) how prenatal and early postnatal risks differentiate these two groups. Method: To identify heterogeneity in early-onset conduct problems, the authors used data from a large longitudinal population-based cohort of children followed from the prenatal period to age 13. Predictive risk factors examined were prenatal and postnatal measures of maternal distress (anxiety, depression), emotional and practical support, and family and child characteristics (from birth to 4 years of age). Results: Findings revealed a distinction between early-onset persistent versus childhood-limited conduct problems in youths. Robust predictors of the early-onset persistent trajectory were maternal anxiety during pregnancy (32 weeks gestation), partner cruelty to the mother (from age 0 to 4 years), harsh parenting, and higher levels of child undercontrolled temperament. Sex differences in these risks were not identified. Conclusions: Interventions aiming to reduce childhood conduct problems should address prenatal risks in mothers and early postnatal risks in both mothers and their young children.

The DSM-IV (1) categorizes the diagnosis of conduct disorder into subtypes by age at onset, i.e., children who show conduct symptoms early in development are expected to be at higher risk for persistent conduct disorder and the development of antisocial personality disorder than their adolescent-onset peers. Extensive research has supported the utility of this distinction (2) . Studies have also highlighted that among early-onset youths, at least 50% do not continue to exhibit high levels of conduct problems later in development (2 – 4) . Such heterogeneity within early-onset groups poses challenges for clinicians, interventionists, and researchers alike. As a high priority for planning in DSM-V, Moffitt and colleagues (5) highlighted research designed to identify differences between children whose early conduct problems do versus do not persist.

Relatively little is known currently about factors that may distinguish these two groups. Similar to children with persistent early-onset conduct problems, those whose problems remit with development (often now referred to as “childhood-limited” groups) have been shown to suffer from early family adversity, parental psychopathology, low intelligence, and undercontrolled temperament (5 – 8) . Nevertheless, compared with childhood-limited subgroups, it has been suggested that youths with persistent conduct problems are more likely to have suffered head injury (7) , have mothers with family histories of alcohol abuse (9) , and have slightly higher levels of hyperactivity and parental criminality (6) . Hence, although the persistent and childhood-limited pathways appear to share many risk factors in common, there may also be distinct child- and family-based risks.

In broader discussions of the persistence of severe conduct problems during early childhood, it has been suggested that young children with high levels of early undercontrolled temperament and aggression and those exposed to negative parenting and family stress are most likely to evince continuing behavior problems at school entry (10 , 11) . In addition, maternal stress can, of course, begin (and indeed already be present) at the time of the conception of the child (12) . Studies have shown that if a woman is anxious and/or depressed during pregnancy, her child is substantially more likely to have cognitive and emotional problems, be temperamentally irritable, and show behavioral problems and/or hyperactivity (13 , 14) , all of which might be expected to increase the risk of an early-onset persistent pathway. At this stage, however, little is known about the extent to which prenatal anxiety and/or depression may differentially predict persistent and childhood-limited trajectories of conduct problems.

Using the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, a longitudinal population-based cohort, we examined the extent to which we could identify heterogeneity in early-onset conduct problems by analyzing distinctive developmental trajectories (15) from early childhood to the teenage years. We then sought to differentiate childhood-limited and early-onset persistent pathways via risks, measured early in the child’s development, associated with the family (including parental psychopathology and maternal family history of alcohol abuse), the child (including undercontrolled temperament and intellectual functioning), and the child’s experiences (including exposure to parental conflict, harsh parenting, and head injury). We then sought to identify the most robust independent risks and potential sex differences in these risks.

Method

Sample

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children is an ongoing population-based study designed to investigate the effects of a wide range of influences on the health and development of children. Pregnant women residing in south-west England who had an estimated date of delivery between April 1, 1991, and December 31, 1992, were invited to participate in the study. The study cohort consisted of 14,541 pregnancies and 13,971 singletons/twins who were still alive at 12 months of age. When compared with the 1991 U.K. National Census Data, the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children sample was found to be similar to the U.K. population as a whole, except the study sample showed a slightly higher proportion of married or cohabiting mothers and families who were owner-occupiers of their residences and (consistent with the area where the study is based) a smaller proportion of mothers from ethnic minorities (4.1% versus 7.6%) (16) . Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children Law and Ethics Committee and the local Research Ethics Committees. Additional, more detailed information about the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children is available online at http://www.bris.ac.uk/alspac/.

Measures

Mothers completed questionnaires at multiple time points during their pregnancy and their child’s infancy and childhood. Data on childhood conduct problems were collected from ages 4 to 13 years. The early childhood predictors examined in the present study were drawn from questionnaires completed between 32 weeks antenatal and 4 years of age.

Repeated assessments of child conduct problems during the past year were measured at ages 4, 7, 8, 10, 12, and 13 years by maternal reports of conduct problems using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (17) . The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire is a widely used screening measure with extensive psychometric support (www.sdqinfo.com). The questionnaire assesses conduct problems with the following five items: 1) “often has temper tantrums or hot tempers”; 2) “generally obedient, usually does what adults request”; 3) “often fights with other children or bullies them”; 4) “often lies or cheats”; and 5) “steals from home, school or elsewhere.” We created binary indicators (0=not high risk; 1=high risk) at each age based on national norms established for 5- to 10-year-old boys and girls in England and Wales (18) . The cutoffs used in the present study are strong predictors of conduct disorder (17) .

Family Characteristics

Socioeconomic status, marital status/cohabitation, and age of the mother at the birth of the child were each reported at 18 weeks postnatal. Socioeconomic status was coded via the Registrar General’s social class scale (19) . We compared mothers in classes IV and V (low socioeconomic status) with those in classes I, II, and III. Marital status reflected 1) no partner/no cohabitation, 2) not married but cohabiting, and 3) married/cohabiting. The age of the mother (mean=24.34 [SD=4.99] years) was dichotomized to contrast mothers who gave birth during their teens (e.g., age 19 and younger, code=1) with older mothers (code=0).

Maternal education was coded according to the mother’s highest level of education (at 32 weeks antenatal) as follows: 1) Certificate of Secondary Education or vocational qualifications only (basic school unfinished/some vocational training); 2) “O” level (minimum qualifications typically required for entry into further education at the time the study began); or 3) “A” level or higher (higher school-based academic qualifications [typically awarded at age 18], along with degrees and other postschool qualifications).

Drinking during pregnancy (18 weeks antenatal [e.g., risk was considered at least 2 units per day]), smoking during pregnancy (18 weeks antenatal [e.g., “yes” smoked cigarettes]), any maternal contact with the police (at child ages 0 to 2 years and/or 2 to 4 years), and maternal family history of alcohol use (17 weeks postnatal [e.g., “yes” mother’s mother or father had an alcohol abuse problem]) were all obtained between pregnancy and when the child was approximately 4 years of age. Each variable was dichotomized to indicate risk (coded 1) or nonrisk (coded 0).

Birth Information

Child birth weight, gestational age, and birth complications (e.g., abruption, preterm rupture, cervical suture) were recorded at the time of birth. Birth complications were dichotomized to contrast mothers with any complications (coded 1) versus those without complications (coded 0). Parity was obtained at 18 weeks gestation from a series of questions about previous pregnancies. Multiparous mothers were coded 1 and primiparous mothers were coded 0.

Child Characteristics

Language development was assessed using the McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities (20) at 24 months postpartum.

Child temperament was assessed with the Carey Infant Temperament Scale (21) at 24 months postpartum. The following four scales, thought to be most representative of undercontrolled temperament, were included: activity, adaptability, intensity, and mood.

Child Experiences

Maternal depression and anxiety were assessed using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (22 , 23) and the Crown-Crisp Experiential Index (24 , 25) , respectively, at 32 weeks antenatal and 8 weeks postnatal. A cutoff of 13 has been found to be a good predictor of clinical depression (23) , which was used in the present study. A cutoff of the top 15% was used for maternal anxiety, since it has been shown to predict both emotional and behavioral difficulties in children at 4 years of age and individual differences in cortisol levels in children at 10 years of age (25) .

Harsh parenting was assessed at age 24 months by the mothers answering the question, “When you are at home with your child, how often do you do the following”: 1) shout at him/her and/or 2) slap him/her. The response scale (reversed coded) was from 1 (everyday) to 5 (rarely/never).

Data pertaining to partner cruelty to the mother (child’s age 0 to 2 years; child’s age 2 to 4 years [e.g., any indication of emotional and/or physical abuse from the mother’s partner]), low emotional support for the mother (during pregnancy; child’s age 0 to 2 years [e.g., the mother having no one with whom to discuss her feelings]), and low practical support for the mother (during pregnancy; child’s age 0 to 2 years [e.g., whether there was anyone who could give the mother financial support and/or to whom the mother could turn in times of trouble]) were collected between pregnancy and when the child was approximately 4 years of age. Each variable was dichotomized to indicate risk (coded 1) or nonrisk (coded 0).

Data pertaining to child head injury were collected at multiple ages. We examined reports obtained at age 54 months that indexed whether or not the child had become unconscious as a result of a head injury at 0 to 2 years of age or 3 to 4 years of age.

Maternal attitude toward the child was measured via the following four questions targeting variations in parental attitudes at 33 months postpartum: 1) “I really enjoy this child”; 2) “Having this child makes me feel fulfilled”; 3) “I would have preferred that we not had this child when we did” (reverse coded); and 4) “I dislike/hate the mess that surrounds this child.” Response scales (reverse coded) varied from 1 (agree) to 4 (disagree).

Attrition and Missing Data

Participants with at least four data points for conduct problems were allowed into the analysis. This resulted in a sample size of 7,218 children (boys=51%). We tested all risk factors for child conduct problems as predictors of exclusion from the analyzed sample. Mothers who were excluded from the present analysis were higher for certain sociodemographic risk factors (teen motherhood: odds ratio [OR]=1.42; maternal education: no basic qualifications, OR=1.98; no mid-level qualifications, OR=1.50]) and maternal smoking during pregnancy (OR=1.64). No other mother or child factors were associated with exclusion from the present analysis. Inevitably, there were also some missing responses for the early childhood predictors, although the effect was minimal within the selected sample (range=0.01%–7%).

Analyses

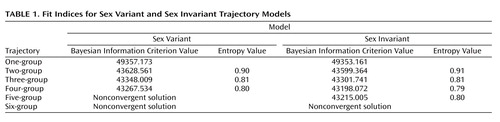

The analyses proceeded in three steps. First, models for the developmental trajectories were estimated for mother-rated conduct problems. Growth mixture models (26) were used to estimate the trajectories in Mplus, Version 4.2 (27) . A series of models was fitted beginning with a one-group trajectory model and moving to a six-group trajectory model. All models were estimated with random starting values. We also compared models that allowed boys and girls to vary in growth parameters of trajectory groups (variant) with models for which we restricted the growth parameters of each individual trajectory to be the same for boys and girls (invariant). When constraining growth parameters in Mplus (27) , the statistical indices available to establish the best fit model are via the Bayesian Information Criterion (28) and entropy. The Bayesian Information Criterion is a commonly used fit index in which lower values indicate a more parsimonious model. Entropy is a measure of classification accuracy with values closer to 1 indexing greater precision (range=0–1) (29) .

In the second step, we used univariate multinomial logit regressions, in SAS PROC CATMOD (30) , for boys and girls, respectively, to examine the capacity of family characteristics, child characteristics, and child experiences to distinguish membership of the persistent and childhood-limited trajectories. Cases were weighted by the posterior probabilities of trajectory membership.

In the third step, we used multivariate multinomial logit regressions, for boys and girls, respectively, to identify independent robust risks that would predict trajectory membership above and beyond the variance attributable to the other predictors. We then examined sex interactions between identified significant multivariate predictors.

Results

Step 1: Trajectories

Table 1 contains the fit indices for the sex variant and sex invariant models. Overall, the sex invariant models fit better than the sex variant models. The four-trajectory invariant model had the best Bayesian Information Criterion value, but entropy decreased compared with the two-trajectory and three-trajectory models. We chose to examine the four-trajectory model, since it was consistent with our hypotheses and supported previous longitudinal research (6 – 8) .

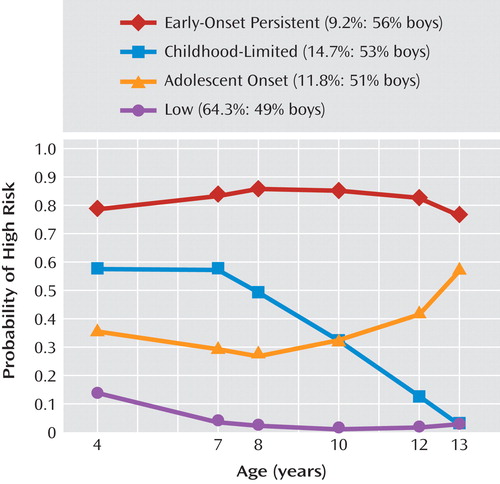

The four trajectories ( Figure 1 ) were 1) early-onset persistent conduct problems (9%), 2) childhood-limited conduct problems (15%), 3) adolescent-onset conduct problems (12%), and 4) children with low involvement in conduct problems (64%). Boys were overrepresented in the early-onset persistent, childhood-limited, and adolescent-onset trajectories.

Step 2: Univariate Predictions for Boys and Girls, Respectively

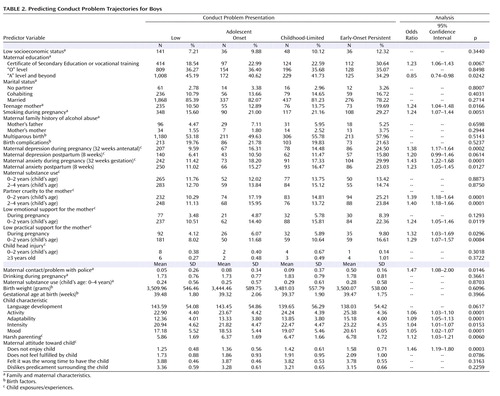

Table 2 demonstrates the contrasts between the persistent and childhood-limited trajectories for boys. Significant predictors for family characteristics were lower levels of maternal education and higher levels of teenage motherhood, maternal trouble with the police, and smoking during pregnancy. For child characteristics, youths with persistent conduct problems had higher levels of all four indicators of undercontrolled temperament. For child experiences, persistent youths had higher levels of exposure to maternal depression and anxiety (both antenatal and postnatal), harsh parenting, partner cruelty to the mother (child age: 0 to 2 years; 2 to 4 years), low emotional support for the mother (child age: 0 to 2 years), and low practical support for the mother (during pregnancy; child age: 0 to 2 years). For maternal attitudes toward the child, boys with persistent conduct problems had mothers who reported that they did not enjoy their child.

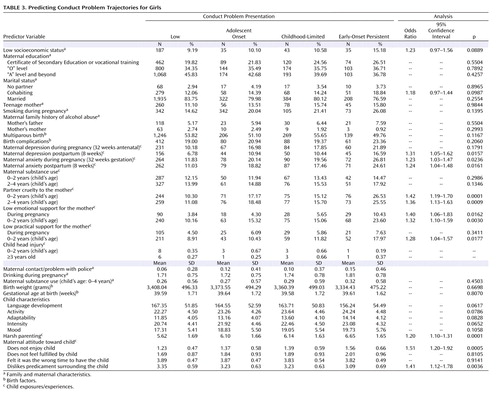

Table 3 shows the contrasts between the persistent and childhood-limited trajectories for girls. Significant predictors for family characteristics included low socioeconomic status and not married but cohabiting mothers. For child characteristics, girls with persistent conduct problems had somewhat higher levels of undercontrolled temperament. For child experiences, girls with persistent conduct problems had mothers with higher levels of depression (postpartum) and anxiety (antenatal and postpartum), harsh parenting, partner cruelty to mother (child age: 0 to 2 years; 2 to 4 years), low emotional support of mother (during pregnancy; child age: 0 to 2 years), and low practical support of mother (child age: 0 to 2 years). For maternal attitudes toward the child, girls with persistent conduct problems had mothers who reported that they 1) did not enjoy the child and 2) hated the mess surrounding the child.

Step 3: Multivariate Predictions for Boys and Girls, Respectively, and Combined

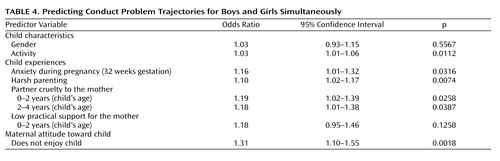

For boys, significant multivariate predictors of the persistent versus childhood-limited contrasts were 1) temperamental activity levels, 2) maternal prenatal anxiety, 3) low maternal enjoyment of the child, and 4) partner cruelty toward the mother (child age: 2 to 4 years). For girls, significant predictors were 1) harsh parenting, 2) partner cruelty toward the mother (child age: 0 to 2 years), and 3) low practical support for the mother (child age: 0 to 2 years).

Table 4 demonstrates the multivariate solution for boys and girls simultaneously. Sex interactions were not significant and are therefore not shown. All predictors remained significant, except practical support for the mother. In summary, factors that increased the risk of the persistent conduct problems trajectory relative to the childhood-limited conduct problems trajectory, for both boys and girls, were 1) temperamental activity levels, 2) anxiety during pregnancy, 3) harsh parenting, and 4) partner cruelty toward the mother.

Discussion

The present results, based on a prospectively studied U.K. birth cohort, support the distinction between early-onset persistent conduct problems versus childhood-limited conduct problems in youths, for both boys and girls. Consistent with prior research, we found that of the 24% of the sample identified with high levels of conduct problems in early childhood, more than 60% decreased to minimal levels of behavioral difficulty by early adolescence. Such developmental variations pose a challenge for intervention and screening in early childhood and suggest that assessing child behavior problems alone will not identify the most seriously at-risk groups. Positive findings of the present research are that the persistent and childhood-limited trajectories could be differentiated based on the range and severity of prenatal and early postnatal risks. These results therefore present evidence for potential improvement in diagnoses and screening as well as support for the importance of preventive interventions starting prior to the birth of the child (12 , 31) .

The present findings suggest that prenatal and early postnatal stress related to the mother is extremely important for the development of the child. At the bivariate level, clinically significant levels of maternal anxiety and depression, during both prenatal and postnatal periods, were higher for the persistent conduct problems group relative to the childhood-limited conduct problems group. When examined in a multivariate solution, maternal anxiety in the last trimester of pregnancy was the sole remaining significant predictor, perhaps suggesting that maternal stress at critical periods of development may alter the programming of the fetal brain, thereby increasing susceptibility to psychopathology (32) . These associations, focusing on differing developmental patterns of conduct problems over time, extend past reports that maternal anxiety in late pregnancy predicts vulnerability to psychopathology in the offspring (25 , 33) .

However, this in itself does not prove that fetal programming has occurred. Two alternate interpretations have also been suggested. First, a mother who experiences anxiety during pregnancy may also have had high levels of anxiety prior to the conception of the child. Hence, the mechanism of transmission could be the transfer of genetic susceptibility to psychopathology (13) , with the possibility that gene-environment effects occur for vulnerable children (25 , 34) . Second, if a mother is stressed during pregnancy, she may also continue to experience stress during the postpartum period. Additional sources of maternal postpartum stress (child age: 0 to 2 years) identified in the present study were partner cruelty to the mother and low practical support for the mother. Combined, multiple stressors in the pre- and postnatal period could affect parenting quality and maternal perceptions of child behavior (13) . Indeed, compared with the childhood-limited group, mothers of youths with persistent conduct problems in the present sample reported higher levels of “not enjoying the child” and of harsh parenting.

These negative parenting attitudes and behaviors may also, in part, reflect a response to the characteristics of the child (35) . Consistent with prior research, we found that the most robust child effect differentiating the persistent and childhood-limited trajectories was high levels of temperamental activity, which is also a robust precursor of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (36 , 37) —itself a known risk and maintaining factor for chronic conduct problems. Future research should examine whether negative parenting is a precursor to and predictor of child temperamental features or whether there is a bidirectional parent-child process (35 , 38) .

Limitations

The present results should be interpreted in the context of five main limitations. First, most measures were based on maternal reports, raising the possibility of shared method variance. Future studies should incorporate multiple informants as well as biological indices (e.g., cortisol) of prenatal maternal stress. Second, although the mothers and children of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children represent a broad spectrum of socioeconomic status backgrounds, the sample includes relatively low rates of ethnic minorities. The present results will need replication with more ethnically diverse samples. Third, we did not support prior research that reported family history of alcohol abuse and head injuries as risks that differentiated the persistent and childhood-limited pathways. Possible reasons for these disparate findings might be that 1) the measure of family history of alcohol problems was not as detailed in the present study as it was in the prior report (9) and 2) we examined head injuries up to age 3, whereas the prior study examined injuries up to age 17 and, hence, could not differentiate whether head injury was a predictor or result of persistent conduct problems (7) . Fourth, similar to most large longitudinal cohorts, the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children has faced attrition over time. As expected, younger and more socially disadvantaged mothers were more likely to be lost to follow-up. Because these predictors of attrition are also predictors of child conduct problems, our sample almost certainly underrepresents children with the most severe difficulties. However, by the same token, we anticipate that the risk associations we detected are also likely to have been attenuated. A recent study based on the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children cohort (39) confirmed that although attrition affected the prevalence rates of antisocial behaviors and related disorders, associations between risks and outcomes remained intact (although conservative estimates of the likely true effects). Finally, we focused on prenatal and early postnatal risks assessed prior to age 4. Later child- and family-based risks may also contribute to differentiating and maintaining early behavioral trajectories and are important targets for future study.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to 1) explicitly examine predictive differences in youths with early-onset persistent conduct problems versus youths with childhood-limited conduct problems and 2) extend the set of risk markers earlier in development (i.e., to the prenatal and early postpartum periods) compared with previous research. Using a large longitudinal cohort, we highlighted that maternal anxiety, both prenatal and early postpartum, is critical in differentiating youths with persistent conduct problems from youths with childhood-limited conduct problems. The results support intervention efforts that “start at the beginning” (40) and offer high-risk mothers health and psychological support beginning with their first obstetric screening (31) . Such efforts should identify mothers-to-be, in particular, by their levels of prenatal anxiety and offer practical support pertaining to parenting, conflict resolution with partners, and guidance for coping with child temperamental features.

1. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 1994Google Scholar

2. Moffitt TE: Life-course persistent versus adolescence-limited antisocial behavior, in Developmental Psychopathology: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation, Vol 3. Edited by Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ. New York, John Wiley and Sons, 2006, pp 570–598Google Scholar

3. Robins LN: Deviant Children Grown Up. Baltimore, Williams and Wilkins, 1966Google Scholar

4. Nagin DS, Tremblay RE: Trajectories of boys’ physical aggression, opposition, and hyperactivity on the path to physically violent and nonviolent juvenile delinquency. Child Develop 1999; 70:1181–1196Google Scholar

5. Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Jaffee S, Kim-Cohen J, Koenen KC, Odgers CL, Slutske WS, Viding E: Research review: DSM-V conduct disorder: research needs for an evidence base. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2008; 49:3–33Google Scholar

6. Odgers CL, Caspi A, Broadbent JM, Dickson N, Hancox R, Harrington H, Poulton R, Sears MR, Thompson M, Moffit TE: Conduct problem subtypes in males predict differential adult health burden. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007; 64:476–484Google Scholar

7. Raine A, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Lynam DR: Neurocognitive impairments in boys on the life-course persistent antisocial path. J Abnorm Psychol 2005; 114:38–49Google Scholar

8. Odgers CL, Moffitt TE, Broadbent JM, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Poulton R, Sears MR, Thompson WM, Caspi A: Female and male antisocial trajectories: from childhood origins to adult outcomes. Dev Psychopathol 2008; 20:673–716Google Scholar

9. Odgers CL, Milne B, Caspi A, Crump R, Poulton R, Moffitt TE: Predicting prognosis for the conduct-problem boy: Can family history help? J Am Acad Adolesc Child Psychiatry 2007; 46:1240–1249Google Scholar

10. Campbell SB, Shaw DS, Gilliom M: Early externalizing behavior problems: toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Dev Psychopathol 2000; 12:467–488Google Scholar

11. Campbell SB: Behavior problems in preschool children: a review of recent research. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1995; 36:113–149Google Scholar

12. Tremblay RE: Understanding development and prevention of chronic physical aggression: towards experimental epigenetic studies. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2008; 363:2613–2622Google Scholar

13. Talge NM, Neal C, Glover V: Antenatal maternal stress and long-term effects on child neurodevelopment: How and why? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2007; 48:245–261Google Scholar

14. Weinstock M: The long-term behavioural consequences of prenatal stress. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2008; 32:1073–1086Google Scholar

15. Muthén B: Latent variable analysis: growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data, in Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences. Edited by Kaplan D. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage Publications, 2004, pp 345–368Google Scholar

16. Golding J, Pembrey M, Jones R: ALSPAC—the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, I: study methodology. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2001; 15:74–87Google Scholar

17. Goodman R: Psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:1337–1345Google Scholar

18. Meltzer H, Gatward R, Goodman R, Ford F: Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in Great Britain. London, HMSO, 2000Google Scholar

19. OPCS: Standard Occupational Classification, Volume 3. London, HMSO, 1991Google Scholar

20. McCarthy D: McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities Manual. New York, Psychological Corporation, 1972Google Scholar

21. Carey WB, McDevitt SC: Stability and change in individual temperament diagnosis from infancy to early childhood. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 1978; 17:331–337Google Scholar

22. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R: Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 150:782–786Google Scholar

23. Murray L, Carothers A: The validation of the Edinburgh Post-natal Depression Scale on a community sample. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 157:288–290Google Scholar

24. Birtchnell J, Evans C, Kennard J: The total score of the Crown-Crisp Experiential Index: a useful and valid measure of psychoneurotic pathology. Br J Med Psychol 1988; 61(pt 3):255–266Google Scholar

25. O’Connor TG, Heron J, Golding J, Beveridge M, Glover V: Maternal antenatal anxiety and children’s behavioural/emotional problems at 4 years: report from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Br J Psychiatry 2002; 180:502–508Google Scholar

26. Muthén B, Shedden K: Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using the EM algorithm. Biometrics 1999; 55:463–469Google Scholar

27. Muthén LK, Muthén BO: Mplus: Statistical Analyses With Latent Variables: User’s Guide. Los Angeles, Muthén and Muthén, 1998Google Scholar

28. Raftery AE: Bayesian model selection in social research. Soc Methodol 1995; 25:111–164Google Scholar

29. McLachlan G, Peel D: Finite Mixture Models. New York, John Wiley and Sons, 2000Google Scholar

30. SAS: SAS/STAT User’s Guide, Version 9.1. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, Inc, 2005Google Scholar

31. Olds D, Henderson CR, Cole R, Eckenrode J, Kitzman H, Luckey D, Pettitt L, Sidora K, Morris P, Powers J: Long-term effects of nurse home visitation on children’s criminal and antisocial behavior: 15-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998; 280:1238–1244Google Scholar

32. Gunnar M, Quevedo K: The neurobiology of stress and development. Annu Rev Psychol 2007; 58:145–173Google Scholar

33. O’Connor TG, Ben-Shlomo Y, Heron J, Golding J, Adams D, Glover V: Prenatal anxiety predicts individual differences in cortisol in pre-adolescent children. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 58:211–217Google Scholar

34. Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, McClay J, Mill J, Martin J, Braithwaite A, Poulton R: Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science 2003; 301:386–389Google Scholar

35. Larsson H, Viding E, Rijsdijk FV, Plomin R: Relationships between parental negativity and childhood antisocial behavior over time: a bidirectional effects model in a longitudinal genetically informative design. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2008; 36:633–645Google Scholar

36. Foley M, McClowry SG, Castellanos FX: The relationship between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and child temperament. J Appl Dev Psychol 2008; 29:157–169Google Scholar

37. Anckarsater H, Stahlberg O, Larson T, Hakansson C, Jutblad S-B, Niklasson L, Nyden A, Wentz E, Westergren S, Cloninger C, Gillberg C, Rastam M: The impact of ADHD and autism spectrum disorders on temperament, character, and personality development. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 167:1239–1244Google Scholar

38. Patterson GR: Coercive Family Process. Eugene, Ore, Castalia, 1982Google Scholar

39. Wolke D, Waylen A, Samara M, Steer C, Goodman R, Ford T, Lamberts K: Does selective dropout in longitudinal studies lead to biased prediction of behaviour disorders? Br J Psychiatry (in press)Google Scholar

40. Tremblay RE: Prevention of youth violence: Why not start at the beginning? J Abnorm Child Psychol 2006; 34:480–486Google Scholar