Major Depression and Antidepressant Treatment: Impact on Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcomes

Abstract

Objective: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use during pregnancy incurs a low absolute risk for major malformations; however, other adverse outcomes have been reported. Major depression also affects reproductive outcomes. This study examined whether 1) minor physical anomalies, 2) maternal weight gain and infant birth weight, 3) preterm birth, and 4) neonatal adaptation are affected by SSRI or depression exposure. Method: This prospective observational investigation included maternal assessments at 20, 30, and 36 weeks of gestation. Neonatal outcomes were obtained by blinded review of delivery records and infant examinations. Pregnant women (N=238) were categorized into three mutually exclusive exposure groups: 1) no SSRI, no depression (N=131); 2) SSRI exposure (N=71), either continuous (N=48) or partial (N=23); and 3) major depressive disorder (N=36), either continuous (N=14) or partial (N=22). The mean depressive symptom level of the group with continuous depression and no SSRI exposure was significantly greater than for all other groups, demonstrating the expected treatment effect of SSRIs. Main outcomes were minor physical anomalies, maternal weight gain, infant birth weight, pregnancy duration, and neonatal characteristics. Results: Infants exposed to either SSRIs or depression continuously across gestation were more likely to be born preterm than infants with partial or no exposure. Neither SSRI nor depression exposure increased risk for minor physical anomalies or reduced maternal weight gain. Mean infant birth weights were equivalent. Other neonatal outcomes were similar, except 5-minute Apgar scores. Conclusions: For depressed pregnant women, both continuous SSRI exposure and continuous untreated depression were associated with preterm birth rates exceeding 20%.

The prevalence of major depressive disorder in women is highest during the childbearing years (1) . Maternal depression is associated with perinatal risk related to physiological sequelae of the disorder and maternal behaviors, such as smoking, substance abuse, and inadequate obstetrical care. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant therapy is common among childbearing-aged women, with 2.3% of pregnant women per year exposed (2) .

Although the majority of early reports (3 – 7) of SSRI treatment during pregnancy did not identify an increased risk for birth defects, in 2005 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an advisory indicating that early exposure to paroxetine may increase the risk for cardiac defects (http://www.fda.gov/CDER/Drug/advisory/paroxetine200512.htm). In response, two large-scale case-control studies were published (8 , 9) . Overall, SSRI exposure was not associated with congenital heart problems or the majority of other categories of birth defects in either investigation. The authors (8 , 9) and Greene (10) concluded that SSRI exposure is associated with a small absolute risk (if any) for major defects.

Findings on the relationship of minor physical anomalies to SSRI exposure have been inconsistent. The occurrence of three or more minor anomalies is important because of its predictive association with major structural malformations (11) , neurodevelopmental abnormalities, or eventual psychiatric problems (12) . Although a higher risk for three or more minor anomalies in fluoxetine-exposed infants was reported (6) , no increased risk was found in newborns exposed to sertraline (13) or SSRIs generally (14) , compared to unexposed newborns.

The landmark 1996 publication by Chambers et al. (6) shifted investigative attention beyond first-trimester SSRI treatment and malformations to later exposure and other reproductive outcomes. Significantly lower maternal weight gain and infant birth weight were reported after exposure to fluoxetine after 25 weeks’ gestation (6) . Subsequent investigators reported that compared to unexposed infants, newborns exposed to SSRIs had a mean birth weight 188 g lower (14) and a significantly higher proportion below the 10th percentile in weight (15) . Birth weights in SSRI-exposed neonates also have been comparable to those of unexposed infants in several investigations (4 , 5 , 16) ; similarly, maternal weight gain also was equivalent (4 , 5) .

Chambers et al. (6) observed a threefold increase in the rate of preterm birth (14.3%) in infants whose mothers took fluoxetine in late pregnancy, relative to infants whose mothers discontinued the drug earlier (4.1%) or were unexposed (5.9%). An association between maternal SSRI treatment and preterm birth has since been reported by many (7 , 14 , 17 – 19) but not all (3 – 5 , 16 , 20) investigators. Preterm birth, the leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality in the United States, occurs in 12.5% of neonates (21) .

Neonates exposed in late pregnancy have a threefold higher risk for neonatal syndrome (CNS, motor, and respiratory signs), which resolves within 2 weeks after birth (22) . Chambers et al. reported that nearly one-third (31.5%) of neonates exposed to fluoxetine in the final trimester had poor neonatal adaptation, compared to 8.9% of neonates with earlier exposure only (6) . Several investigators (14 , 16 , 23 , 24) have reported less favorable Apgar scores associated with third-trimester SSRI exposure. A specific association between late-pregnancy fluoxetine exposure and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn has been reported (25) . Two (2.7%) of 73 exposed infants developed persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn, a rate six times that in the general population (0.1–0.2%). Additional reports of neonatal respiratory distress after SSRI exposure have been published (15 , 24 , 26) .

We conducted a prospective observational study to determine whether either SSRI treatment or untreated depression in pregnant women with major depressive disorder, compared to unexposed pregnant women without major depression, was associated with increased risk for 1) minor physical anomalies, 2) reduced maternal weight gain and infant birth weight, 3) preterm birth, or 4) poor neonatal outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the only prospectively followed study group with subgroups for both continuous and partial exposures to depression and SSRIs.

Method

In this prospective observational study, maternal assessments were completed at weeks 20, 30, and 36 weeks of gestation. Delivery records were reviewed and the newborns examined at 2 weeks postpartum.

Study Subjects

The pregnant women were 15–44 years old and were recruited from two sites. Twenty-one were enrolled in Cleveland between Jan. 23, 2000, and April 1, 2001, and 217 were recruited in Pittsburgh between April 23, 2003, and July 11, 2007. Recruitment was by self-referral, physician referral, advertising, and screening in obstetrical ultrasound suites. Approval was obtained from the Case Western Reserve University and University of Pittsburgh institutional review boards. All women provided written informed consent.

After evaluating the patterns of SSRI and depression exposure that occurred in our subjects, we created five nonoverlapping groups:

1. No SSRI, no depression (N=131)—no exposure to any antidepressant or to major depressive disorder.

2. Continuous SSRI exposure (N=48)—treatment with an SSRI during the entirety of pregnancy or for the majority of each of the three trimesters.

3. Continuous depression, no SSRI (N=14)—the presence of major depression throughout pregnancy or for the majority of each of the three trimesters, without SSRI treatment.

4. Partial SSRI exposure (N=23)—treatment with an SSRI at some point during pregnancy but at least one full trimester without exposure; this group was equally split between women treated with an SSRI in the first and/or second trimester, but not the third, and women treated in the second and/or third trimester, but not the first.

5. Partial depression, no SSRI (N=22)—major depressive disorder at some point during pregnancy but no depression for at least one trimester, without SSRI treatment.

Consultation about depression management during pregnancy was provided to women with depression or SSRI exposure, and a summary was sent both to the woman and to her physician(s). Enrollment did not depend on acceptance of the recommendations or treatment choice. No intervention was prescribed by the study team.

Exposures

Beginning with conception, SSRI exposure was documented by charting each subject’s drug doses across each week of gestation. Because we observed that nearly 15% of the drug-treated childbearing women in a previous randomized SSRI trial had negligible serum levels (27) , we confirmed exposure (maternal serum level ≥10 ng/ml) for inclusion in the SSRI-treated groups. Women with active substance use disorder (identified by self-report or urine drug screen) or with gestational exposure to benzodiazepines or prescription drugs in the FDA-defined category of D or X were excluded. Exposures to prescribed drugs, over-the-counter medications, environmental agents, alcohol, and smoking were recorded at each assessment.

The diagnosis of major depressive disorder was made according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID). We adapted the timeline technique (28) to chart depression course by month across the pregnancy. Women with psychosis or bipolar disorder were excluded. Those with multiple gestations or chronic diseases were also excluded.

Outcomes

Descriptive data for the sample included demographic characteristics, smoking status, alcohol intake, parity, and previous preterm births. Depression severity was assessed with the 29-item Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale With Atypical Depression Supplement (SIGH-ADS) (29) , which includes all versions of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. The functional measures were the Global Assessment Scale from the SCID and the SF-12 Health Survey (30) , which yields summary scores for the physical and mental components.

The main outcome measures were minor physical anomalies, maternal weight gain, infant birth weight, pregnancy duration, and neonatal characteristics. To assess minor anomalies, an infant examination was performed at 2 weeks postbirth by a physician (D.L.B.) or pediatric nurse practitioner blind to maternal exposures. The minor anomalies measure was initially developed at the National Institute of Mental Health (12) to evaluate dysmorphology in children. Minor anomalies specific to teratogen exposure were added (by K.L.W.) specifically for use in drug-exposed pregnant women. The expanded measure was successfully used to compare minor anomalies in infants exposed prenatally to alcohol with unexposed comparison infants (31) .

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from the mother’s prepregnancy weight and height. Maternal gestational weight was recorded at each evaluation. The Institute of Medicine guidelines (32) were used to define categories of both prepregnancy BMI status and adequacy of pregnancy weight gain. Infant birth weight, length, and head circumference and other outcome data were obtained by review of delivery records by independent evaluators (D.F.H. and S.J.-I.) blind to study hypotheses and design. Designations of small (<10th percentile) and large (>90th percentile) for gestational age were standardized by sex.

Preterm birth was subcategorized as late (34 to <37 weeks) and early (<34 weeks). Measures to assess neonatal adaptation included delivery method, Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes, admission to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and item scores on the infant subscale of the Peripartum Events Scale (33) . The infant subscale of this measure includes 10 problems (pH correction, volume expansion, transfusion, hypoglycemia, hyperbilirubinemia, hypocalcemia, sepsis, meconium aspiration pneumonitis, other, and other life-threatening). The infant subscale was divided into two categories: one or no problems versus two or more problems; the latter category reflected the most affected 10% of infants. To evaluate respiratory distress, we identified five variables on the Peripartum Events Scale (tachypnea, required oxygen, respiratory distress, acrocyanosis, cyanosis) that were combined and compared across groups.

Statistical Methods

Demographic and historical variables were compared with Pearson chi-square statistics or Fisher exact statistics (for variables with expected cell frequencies of less than 10) for categorical variables and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous measures. Post hoc comparisons were done for variables with significance levels of p<0.05. Outcome measures were compared with regression models. Unadjusted models were performed with the five exposure groups and followed with adjustment for maternal age and race, which were selected because they had prominent effects on reproductive outcomes and were demographic variables that significantly differed among exposure groups.

We analyzed differences in minor physical anomalies 1) among infants exposed to SSRIs, depression, or neither in the first trimester and 2) among the five groups. Minor anomalies were analyzed both as frequency counts with Poisson regression and as a dichotomized variable (fewer than three versus three or more) with logistic regression. Prepregnancy BMI, weight gain at week 36, and infant birth weight were analyzed with linear regression. Categorical prepregnancy BMI and infant birth weight and the proportion of women within Institute of Medicine guidelines for weight gain were analyzed with polychotomous logistic regression.

Gestational age at birth was analyzed both as a continuous measure and as a categorical variable (full term, early preterm, or late preterm). Time to birth across groups was compared with Cox proportional hazard models. The proportions of infants with preterm birth, NICU admission, 1- and 5-minute Apgar scores of 7 or less, Peripartum Events Scale subscale ratings of 2 or higher, and respiratory signs were compared with logistic regression. Adjusted models were not completed for neonatal outcome variables with low frequencies, i.e., fewer than 10 occurrences. Stata version 8.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, Tex.), SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago), and StatXact version 8 (Cytel Corp., Cambridge, Mass.) were used.

Results

Subjects

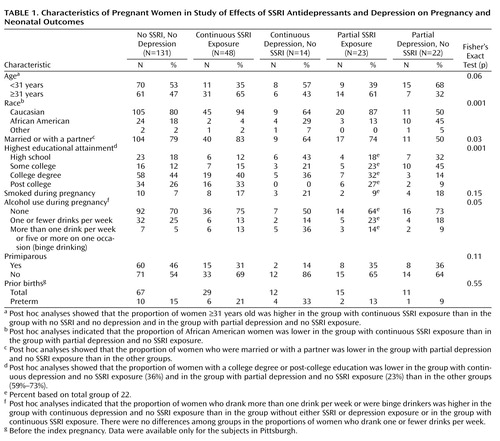

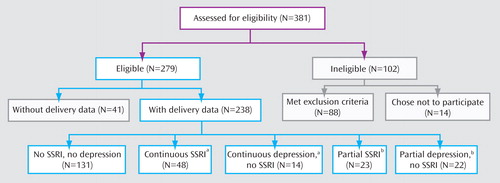

Of the 381 women evaluated, 279 (73%) were eligible and 238 (85%) provided neonatal outcome data ( Figure 1 ). Their characteristics are displayed in Table 1 . Women who took SSRIs continuously tended to be older, Caucasian, married, and more educated. Although pregnant women who reported alcohol abuse or dependence at intake were excluded, subjects with continuous depression who received no SSRI treatment reported more alcohol use (more than 1 drink a week or binge drinking) than either the group receiving continuous SSRIs or the group with no SSRIs and no depression. Unlike many groups of depressed women, the subjects with depression in this study were not significantly more likely to smoke than were antidepressant-treated women or the group without either depression or SSRI treatment.

a The groups with continuous exposure also include women exposed for the majority of each of the three trimesters.

b The groups with partial exposure had at least one trimester free of exposure.

Of the 71 women treated with SSRIs, more than two-thirds (68%) were on maintenance regimens and received SSRIs continuously. The majority of drug use was monotherapy (83%). The SSRIs included sertraline (34%), fluoxetine (25%), and citalopram or escitalopram (23%). Other drug treatments (18%) included fluvoxamine, paroxetine, venlafaxine, and combinations (an SSRI plus bupropion or an SSRI plus a tricyclic antidepressant).

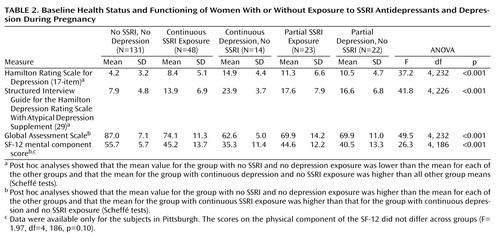

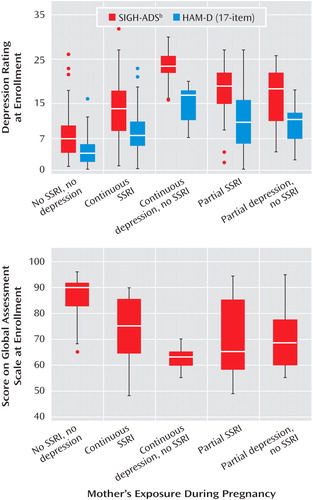

As anticipated, women exposed to neither depression nor SSRIs had significantly lower depressive symptom levels and higher functional status than the exposure groups ( Table 2 , Figure 2 ). The mean symptom level of the group with continuous depression and no SSRI treatment was significantly greater than the levels of all other groups. A parallel pattern was observed for the Global Assessment Scale and the mental component summary of the SF-12. The mean scores of the group with continuous SSRI treatment were significantly greater (indicating higher functioning) than the scores of the group with continuous depression and no SSRI exposure. These observations demonstrate the expected treatment effect in the SSRI group.

a Within each box, the white line represents the median value. The top and bottom edges of the box represent the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively; these define the interquartile range. Each bar attached to the box represents 1.5 times the interquartile range; the filled circles are outliers.

b 29-item Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale With Atypical Depression Supplement (29).

Physical Malformations

Assessments of minor anomalies were available for 203 (85%) of the infants, and 30 (15%) had three or more anomalies. Neither first-trimester nor continuous exposure to SSRIs or depression was associated with a significant increase in the number of minor anomalies or the proportion of infants with three or more anomalies. No major malformations were observed.

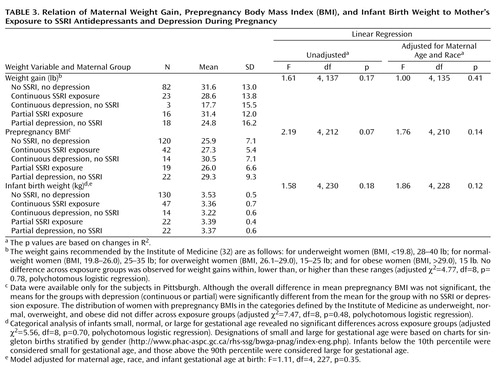

Gestational Weight Gain and Infant Birth Weight

Neither SSRI use nor depression was related to maternal weight gain ( Table 3 ). Although the differences in weight gain among exposure groups were not significant, women with depression had lower mean weight gains than women treated with SSRIs or those who had neither exposure. Conversely, women with depression had nonsignificantly higher mean prepregnancy BMIs than women who received SSRIs or the comparison subjects. Because gestational weight gain recommendations are based on prepregnancy BMI, we evaluated the proportions of women who gained less than, the same as, or more than the ranges in the Institute of Medicine guidelines across subject groups. No significant differences emerged ( Table 3 ).

Neither mean infant birth weight nor the proportion of infants with birth weights below the 10th or above the 90th percentile for gestational age differed across exposure groups ( Table 3 ). Birth length and head circumference also did not differ (data not shown).

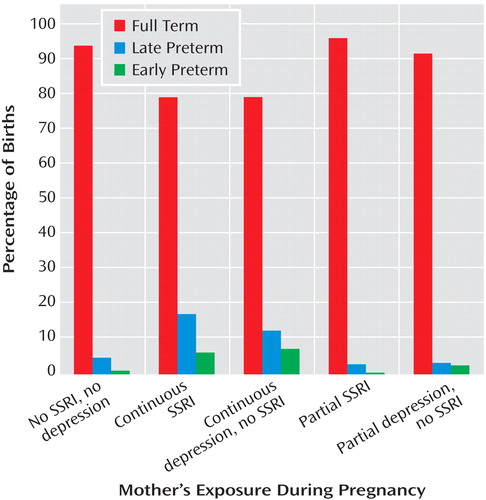

Preterm Birth Rate

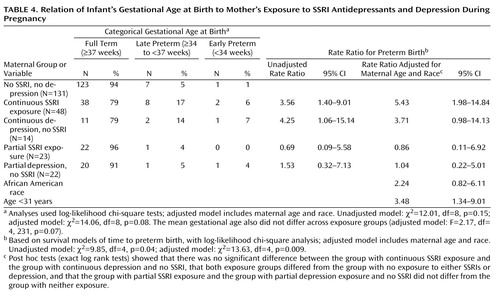

In both the group with continuous depression and the group with continuous SSRI exposure, more than 20% of the infants were delivered preterm and the proportions of late- and early-preterm births were similar. The preterm birth rates in the other groups ranged from 4% to 9% ( Table 4 , Figure 3 ). The relationship between continuous SSRI exposure and preterm birth was stronger after adjustment for maternal age and African American race ( Table 4 ). Gestational age at birth did not differ between women with partial SSRI or depression exposure and the unexposed comparison women.

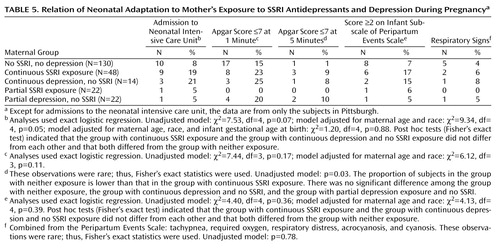

Neonatal Adaptation

No difference among groups for vaginal versus surgical delivery was observed (data not shown). After adjustment for maternal age, race, and gestational age, we found that infants exposed in utero either to continuous SSRIs or continuous depression with no SSRI treatment were not more likely to be admitted to the NICU than infants in other groups ( Table 5 ). The Peripartum Events Scale infant subscale scores and respiratory signs did not differ across groups. Although the proportions of infants with Apgar scores of 7 or higher at 1 minute were similar across groups, significantly more infants had Apgar scores of 7 or more at 5 minutes among the infants of mothers with continuous SSRI exposure than among the unexposed infants ( Table 5 ).

Discussion

In this controlled prospective investigation, we found that gestational exposure to SSRIs or depression (in unmedicated women) was not related to the number of minor physical anomalies in offspring of women with major depressive disorder. This study and two others (13 , 14) have not replicated the original report (6) of a higher rate of minor anomalies in infants exposed prenatally to SSRIs. Moreover, no definitively higher risk for two clinical correlates of minor anomalies—major structural malformations (8 – 10) and neurodevelopmental abnormalities or psychiatric problems (4 , 14 , 15 , 34 , 35) —has been associated with SSRI exposure. However, one investigative team (36) found normal mental but lower psychomotor skills in toddlers exposed prenatally to SSRIs.

Like other researchers (5 , 7 , 18 , 37) , we found that maternal weight gain was not significantly lower in SSRI-treated women with or without adjustment for preconception BMI. We observed that women with unmedicated depression (continuous or partial) tended to have a pattern of higher mean preconception BMI, coupled with lower mean weight gain, than women treated with SSRIs or comparison subjects.

A major finding of this study is a higher risk for preterm birth in infants exposed in utero to either continuous SSRI treatment for depression or continuous depression without SSRI treatment. Our study joins the converging yet controversial literature that links SSRI treatment to a threefold (6 , 14 , 18) increase in the risk for preterm birth. Another important observation is that women exposed to depression (with no SSRI treatment) throughout pregnancy had a comparable level of increased risk for preterm birth.

Attempts to differentiate reproductive outcomes related to SSRIs from those associated with depression have been few (15 , 18) . With a prospective observational design, Suri et al. (18) studied pregnant women in three groups: 1) antidepressant treatment for more than 50% of the pregnancy, 2) major depressive disorder with no treatment, discontinuation of antidepressant in the first trimester, and/or brief antidepressant exposure, and 3) neither exposure. The rates of preterm birth were 14.3%, 0.0%, and 5.3%, respectively. The authors suggested that SSRI treatment, rather than depression, was associated with the higher risk for preterm birth. We found equivalent effects of continuous SSRI treatment and depression exposure on preterm birth.

One explanation for variable research findings is differing characteristics among the study groups. In this investigation, women who received SSRIs continuously had lower depressive symptom scores and better functioning than the women with continuous depression and no SSRI exposure. In contrast, Suri et al. (18) studied medicated and unmedicated pregnant women with depression and observed comparable levels of depression. Additionally, the levels of depressive symptoms and functioning in our group with partial SSRI exposure and the group with partial depression and no SSRI exposure were similar, which emphasizes the differential importance of continuous exposure to either SSRIs or depression. For improving risk-benefit decisions about the treatment of major depressive disorder during pregnancy, the crucial question is whether treated women have more favorable reproductive outcomes compared to unmedicated women.

Another explanation for the lack of consistent findings is the variability in exposure definitions across studies. For example, we found that partial exposure to either SSRIs or depression did not increase the risk for preterm birth. Similarly, Chambers et al. (6) reported that mothers who discontinued SSRIs before the third trimester (similar to our group with partial exposure) had a preterm birth rate comparable to the rate for comparison subjects, while mothers with third-trimester exposure (82% treated throughout pregnancy) had an increased rate. Other investigators have defined exposure as 1) early, with antidepressant use ending before 16 weeks of gestation, without elaboration about later use (7) , 2) late pregnancy (24) , 3) an antidepressant prescription filled during pregnancy (14 , 15) , 4) an antidepressant prescription purchased during trimester 1, 2, or 3 or throughout pregnancy (20) , 5) first trimester (5) , and 6) throughout pregnancy or partial treatment (37) . Standardization of definitions for both SSRI and depression exposures would facilitate cross-study analyses.

In this study group, over 20% of the pregnant women with major depressive disorder who were either continuously treated with an SSRI or continuously exposed to active depression delivered preterm infants. The rates of late- and early-preterm births were similarly distributed. The implication is that a factor common to women with depression who elect continuous treatment or remain unmedicated throughout pregnancy is related to preterm birth. The underlying depressive disorder and its sequelae may constitute a long-term disease risk factor independent of current symptom level. An alternative explanation is that factors independently related to active depression and SSRI treatment during pregnancy are associated with preterm birth and that the effects are of the same order of magnitude. The observation that partial exposure to SSRIs or depression was not associated with a higher rate of preterm births suggests that disease management choices related to the chronicity or severity of depression affect reproductive outcome. These data do not support a recommendation for partial SSRI treatment during pregnancy to reduce the risk of preterm birth.

Demographic characteristics also differed across the five exposure groups. African American women were significantly more likely to have continuous depression and to be unmedicated. Racial disparities in reproductive outcomes, including preterm birth, are well described. Women with continuous SSRI exposure tended to be older, Caucasian, married, and more educated. Caucasian race, maternal age greater than 25 years, and education beyond high school are predictors for antidepressant use during pregnancy (38) .

The majority of the recent increase in preterm births in the United States is attributable to late-preterm neonates, with the mortality rate similar to that for early-preterm infants. The relationship of preterm birth to depression and SSRI exposures must be clarified. Categorization of preterm births as due to obstetrical complications versus spontaneous preterm labor or membrane rupture would be an informative next step.

Contrary to our expectations, neonatal signs other than 5-minute Apgar scores did not differ between infants with continuous SSRI exposure and unexposed infants. A potential explanation for disparate findings across studies is that the study groups were treated with varying proportions of individual SSRI agents. The pharmacological characteristics of individual SSRIs result in different effects on neonatal outcomes (22) . The substantial majority of reports of SSRI-related neonatal syndrome involve paroxetine (22 , 39) , which has a short half-life, strong affinity for muscarinic receptors, and potent inhibition of serotonin reuptake. Costei et al. (26) reported that 22% of neonates exposed to paroxetine had complications that required intensive treatment. Both serotonin withdrawal and cholinergic overdrive may occur in paroxetine-exposed newborns (22) .

Fluoxetine, with a long half-life and active metabolite, is the second most frequent agent associated with neonatal syndrome (22) . The highest reported rates for neonatal syndrome after in utero exposure were 31% (25) in a group exposed only to fluoxetine and 30% (40) among infants exposed to paroxetine (62%) or fluoxetine (20%). In a study by Oberlander et al. (15) in which SSRI-exposed infants had feeding problems and respiratory distress, the majority of exposures were to paroxetine (44.7%) and fluoxetine (27.2%). Our group of women exposed to SSRIs continuously included only two (4%) treated with paroxetine and 10 (21%) treated with fluoxetine.

This investigation has several strengths. First, it is a prospective observational study of women with major depressive disorder who either had treatment with SSRIs or were untreated and experienced depression (both groups were divided into women with continuous and partial exposures), who were compared to a unexposed group. Second, unlike the majority of investigations, this study confirmed SSRI exposure by maternal serum assay. Third, assessments of maternal and infant outcomes were performed by blind raters. Finally, smoking rates did not differ across groups, and women with diagnosed alcohol abuse or dependence, a positive urine drug screen, or any exposure to FDA class D or X agents were excluded.

The weaknesses of this study include the difference in demographic characteristics (age, race, education, and marital status) among the exposure groups. Although adjustments for age and race were made, ideally these characteristics are equally distributed among groups through randomization, which was not ethical with this pregnant population. Second, a larger study group would have allowed us to be more accurate in dividing the SSRI group into categories based on response of the depression to treatment, although the mean scores for depressive symptoms and functioning for the group with continuous SSRI exposure supported benefit from treatment. Also, larger prospective studies would provide enough subjects to evaluate outcomes related to individual SSRIs.

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang PS, National Comorbidity Survey Replication: The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003; 289:3095–3105Google Scholar

2. Reefhuis J, Rasmussen SA, Friedman JM: Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn; reply of Chambers C, Hernandez-Diaz S, Mitchell AA (letter). N Engl J Med 2006; 354:2188–2190Google Scholar

3. Kulin NA, Pastuszak A, Sage SR, Schick-Boschetto B, Spivey G, Feldkamp M, Ormond K, Matsui D, Stein-Schechman AK, Cook L, Brochu J, Rieder M, Koren G: Pregnancy outcome following maternal use of the new selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a prospective controlled multicenter study. JAMA 1998; 279:609–610Google Scholar

4. Nulman I, Rovet J, Stewart DE, Wolpin J, Gardner HA, Theis JG, Kulin N, Koren G: Neurodevelopment of children exposed in utero to antidepressant drugs. N Engl J Med 1997; 336:258–262Google Scholar

5. Pastuszak A, Schick-Boschetto B, Zuber C, Feldkamp M, Pinelli M, Sihn S, Donnenfeld A, McCormack M, Leen-Mitchell M, Woodland C, et al: Pregnancy outcome following first-trimester exposure to fluoxetine (Prozac). JAMA 1993; 269:2246–2248Google Scholar

6. Chambers CD, Johnson KA, Dick LM, Felix RJ, Jones KL: Birth outcomes in pregnant women taking fluoxetine. N Engl J Med 1996; 335:1010–1015Google Scholar

7. Ericson A, Kallen B, Wiholm B: Delivery outcome after the use of antidepressants in early pregnancy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1999; 55:503–508Google Scholar

8. Alwan S, Reefhuis J, Rasmussen SA, Olney RS, Friedman JM, National Birth Defects Prevention Study: Use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2684–2692Google Scholar

9. Louik C, Lin AE, Werler MM, Hernandez-Diaz S, Mitchell AA: First-trimester use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2675–2683Google Scholar

10. Greene MF: Teratogenicity of SSRIs—serious concern or much ado about little? (editorial). N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2732–2733Google Scholar

11. Leppig KA, Werler MM, Cann CI, Cook CA, Holmes LB: Predictive value of minor anomalies, I: association with major malformations. J Pediatr 1987; 110:531–537Google Scholar

12. Waldrop MF, Pedersen FA, Bell RQ: Minor physical anomalies and behavior in preschool children. Child Dev 1968; 39:391–400Google Scholar

13. Chambers CD, Dick LM, Felix RJ, Johnson KA, Jones KL: Pregnancy outcomes in women who use sertraline (abstract). Teratology 1999; 59:376Google Scholar

14. Simon GE, Cunningham ML, Davis RL: Outcomes of prenatal antidepressant exposure. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:2055–2061Google Scholar

15. Oberlander TF, Warburton W, Misri S, Aghajanian J, Hertzman C: Neonatal outcomes after prenatal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants and maternal depression using population-based linked health data. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:898–906Google Scholar

16. Pearson KH, Nonacs RM, Viguera AC, Heller VL, Petrillo LF, Brandes M, Hennen J, Cohen LS: Birth outcomes following prenatal exposure to antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68:1284–1289Google Scholar

17. Lund N, Pedersen L, Henriksen T: SSRI exposure in utero and pregnancy outcome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2006; 19(5 suppl 1):45Google Scholar

18. Suri R, Altshuler L, Hellemann G, Burt VK, Aquino A, Mintz J: Effects of antenatal depression and antidepressant treatment on gestational age at birth and risk of preterm birth. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:1206–1213Google Scholar

19. Wen SW, Yang Q, Garner P, Fraser W, Olatunbosun O, Nimrod C, Walker M: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006; 194:961–966Google Scholar

20. Malm H, Klaukka T, Neuvonen PJ: Risks associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2005; 106:1289–1296Google Scholar

21. Institute of Medicine: Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences and Prevention. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 2007Google Scholar

22. Moses-Kolko EL, Bogen D, Perel J, Bregar A, Uhl K, Levin B, Wisner KL: Neonatal signs after late in utero exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors: literature review and implications for clinical applications. JAMA 2005; 293:2372–2383Google Scholar

23. Laine K, Heikkinen T, Ekblad U, Kero P: Effects of exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy on serotonergic symptoms in newborns and cord blood monoamine and prolactin concentrations. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:720–726Google Scholar

24. Kallen B: Neonate characteristics after maternal use of antidepressants in late pregnancy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004; 158:312–316Google Scholar

25. Chambers CD, Hernandez-Diaz S, Van Marter LJ, Werler MM, Louik C, Jones KL, Mitchell AA: Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:579–587Google Scholar

26. Costei AM, Kozer E, Ho T, Ito S, Koren G: Perinatal outcome following third trimester exposure to paroxetine. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002; 156:1129–1132Google Scholar

27. Wisner KL, Hanusa BH, Perel JM, Peindl KS, Piontek CM, Sit DK, Findling RL, Moses-Kolko EL: Postpartum depression: a randomized trial of sertraline versus nortriptyline. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006; 26:353–360Google Scholar

28. Post RM, Roy-Byrne PP, Uhde TW: Graphic representation of the life course of illness in patients with affective disorder (commentary). Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:844–848Google Scholar

29. Williams J, Terman M: Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale With Atypical Depression Supplement (SIGH-ADS). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 2003Google Scholar

30. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD: A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996; 34:220–233Google Scholar

31. Day NL, Robles N, Richardson G, Geva D, Taylor P, Scher M, Stoffer D, Cornelius M, Goldschmidt L: The effects of prenatal alcohol use on the growth of children at 3 years of age. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1991; 15:67–71Google Scholar

32. Institute of Medicine: Nutrition During Pregnancy. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1990Google Scholar

33. O’Hara M, Varner M, Johnson S: Assessing stressful life events associated with childbearing: the Peripartum Events Scale. J Reprod Infant Psychol 1986; 4:85–98Google Scholar

34. Misri S, Reebye P, Kendrick K, Carter D, Ryan D, Grunau RE, Oberlander TF: Internalizing behaviors in 4-year-old children exposed in utero to psychotropic medications. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1026–1032Google Scholar

35. Nulman I, Rovet J, Stewart DE, Wolpin J, Pace-Asciak P, Shuhaiber S, Koren G: Child development following exposure to tricyclic antidepressants or fluoxetine throughout fetal life: a prospective, controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1889–1895Google Scholar

36. Casper RC, Fleisher BE, Lee-Ancajas JC, Gilles A, Gaylor E, DeBattista A, Hoyme HE: Follow-up of children of depressed mothers exposed or not exposed to antidepressant drugs during pregnancy. J Pediatr 2003; 142:402–408Google Scholar

37. Hendrick V, Stowe ZN, Altshuler LL, Hwang S, Lee E, Haynes D: Placental passage of antidepressant medications. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:993–996Google Scholar

38. Cooper WO, Willy ME, Pont SJ, Ray WA: Increasing use of antidepressants in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007; 196:544.e1–544.e5Google Scholar

39. Sanz EJ, de las Cuevas C, Kiuru A, Bate A, Edwards R: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnant women and neonatal withdrawal syndrome: a database analysis. Lancet 2005; 365:482–487Google Scholar

40. Levinson-Castiel R, Merlob P, Linder N, Sirota L, Klinger G: Neonatal abstinence syndrome after in utero exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in term infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006; 160:173–176Google Scholar