Longitudinal PET Imaging in a Patient With Schizophrenia Did Not Show Marked Changes in Dopaminergic Function With Relapse of Psychosis

To the Editor: To date, eight studies have investigated striatal presynaptic dopaminergic function in psychosis. Of these, six found an elevation of dopaminergic function in schizophrenia patients relative to comparison subjects, one reported no difference between patients and comparison subjects, and another found a small reduction in patients relative to comparison subjects (1) . However, each of these studies was cross-sectional, and it remains unknown whether striatal hyperdopaminergia is a trait marker of psychosis liability or a state factor linked to the acute emergence of psychotic symptoms.

The Hammersmith Hospital Research Ethics Committee approved a longitudinal positron emission tomography (PET) study. After receiving a complete description of the study, a 58-year-old woman, with a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia since the age of 23, provided written informed consent to receive a [ 18 F]-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) PET scan and a symptom rating using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) during a period of remission and again during an acute psychotic relapse 10 months following the remission period. The [ 18 F]-DOPA PET scan was conducted using the same scanner and methods as previously described by Howes et al. (2) in order to determine the influx constant of radiolabelled DOPA in the striatum, which is a measure of presynaptic dopamine synthesis and storage capacity. During the first remission period, total and positive PANSS scores were 55 and 17, respectively, which fulfilled the clinical criteria for remission (3) . During the acute psychotic relapse, total and positive PANSS scores were 119 and 40, respectively, reflecting severe acute psychotic symptoms, with ratings for delusions and hallucinations within the severe or extremely severe range. The patient had not taken any medication or illicit substance for 8 years prior to the scans or throughout the period between scans.

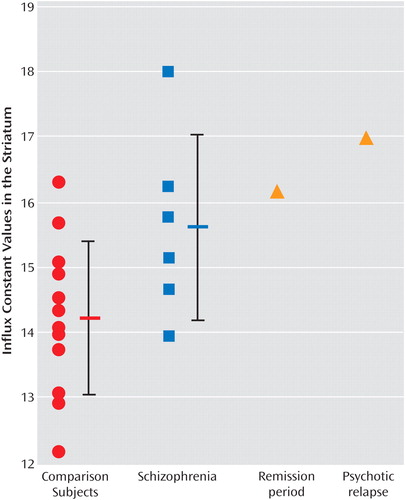

Figure 1 illustrates the patient’s influx constant values at each time point as well as previously published (2) influx constant values for comparison subjects and schizophrenia patients. Relative to comparison subjects, the patient’s influx constant values appeared to be increased during remission (0.0161 minutes -1 ), and these values increased by an additional 5% during the acute psychotic relapse (0.0169 minutes -1 ). However, this difference falls within the test-retest variability of [ 18 F]-DOPA three-dimensional PET influx constant values, reported to be 0%–11% in the striatum (4) , and (as shown in Figure 1) within the standard deviation of the influx constant values for the schizophrenia patients. This finding suggests that the influx constant value changes little, if at all, despite a marked deterioration in clinical state and development of severe acute psychotic symptoms.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of the relationship between dopamine overactivity and psychotic symptoms explored in the same patient during a period of remission and acute psychotic relapse. The finding that influx constant values changed little suggests that hyperdopaminergia is a trait factor associated with schizophrenia rather than a state-related factor that drives symptom development.

The present report provides useful data to guide the design of definitive studies to investigate whether dopaminergic function alters with clinical state. Using the effect size in this report (0.59), a sample size of at least 25 will be required to detect a difference at a significance level of 5%, with 80% power.

1. Howes OD, Montgomery AJ, Asselin MC, Murray RM, Grasby PM, McGuire PK: Molecular imaging studies of the striatal dopaminergic system in psychosis and predictions for the prodromal phase of psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 2007; 51(suppl):S13–S18Google Scholar

2. Howes OD, Montgomery AJ, Asselin MC, Murray RM, Valli I, Tabraham P, Bramon-Bosch E, Valmaggia L, Johns L, Broome M, McGuire PK, Grasby PM: Elevated striatal dopamine function linked to prodromal signs of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psych (in press)Google Scholar

3. Andreasen NC, Carpenter WT Jr, Kane JM, Lasser RA, Marder SR, Weinberger DR: Remission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:441–449Google Scholar

4. Weinhard K: 3D 18 F-Fluorodopa PET: improved kinetics and discrimination in Parkinson’s disease, in The Theory and Practice of 3D PET. Edited by Bendriem B, Townsend DW. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1998, pp 150–154 Google Scholar