Evaluation of the Risk of Congenital Cardiovascular Defects Associated With Use of Paroxetine During Pregnancy

Abstract

Objective: In 2005–2006, several studies noted an increased risk of cardiovascular birth defects associated with maternal use of paroxetine compared with other antidepressants in the same class. In this study, the authors sought to determine whether paroxetine was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular defects in infants of women exposed to the drug during the first trimester of pregnancy. Method: From teratology information services around the world, the authors collected prospectively ascertained, unpublished cases of infants exposed to paroxetine early in the first trimester of pregnancy and compared them with an unexposed cohort. The authors also contacted the authors of published database studies on antidepressants as a class to determine how many of the women in those studies had been exposed to paroxetine and the rates of cardiovascular defects in their infants. Results: The authors were able to ascertain the outcomes of 1,174 infants from eight services. The rates of cardiac defects in the paroxetine group and in the unexposed group were both 0.7%. The rate in the database studies (2,061 cases from four studies) was 1.5%. Conclusions: Paroxetine does not appear to be associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular defects following use in early pregnancy, as the incidence in more than 3,000 infants was well within the population incidence of approximately 1%.

Prior to late 2005, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants as a class were considered relatively safe to take in pregnancy, as they had not been found to be associated with a risk of major malformations above the baseline rate of 1%–3% in the general population. Studies supporting this view included a meta-analysis and two database studies, with a combined total approaching 4,000 pregnancy outcomes (1 – 3) .

In the fall of 2005, GlaxoSmithKline published on its web site the results of a claims database study with the finding that infants exposed in utero to paroxetine may have a higher risk of congenital malformations, in particular cardiovascular defects. The study was based on outcomes of 815 infants, and the reported incidence of cardiovascular malformations, unspecified in terms of severity, was 2% (4) . A more detailed analysis of these data was published recently in which the incidence was adjusted to 1.5% (5) . The latest results of a prospective longitudinal database study in Sweden (6) , which included 959 exposures to paroxetine in early pregnancy, indicated an increased risk of cardiovascular defects of relatively mild types after maternal use of paroxetine, at a rate of 2%. Finally, a small prospective comparative study from a teratology information service, presented as an abstract at a meeting, also documented a higher rate of cardiovascular defects associated with use of paroxetine, at 1.9% (7) .

Based on these three reports, warnings were posted in late 2005 on the web sites of Health Canada (8) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (9) advising women to avoid paroxetine if possible during pregnancy. In December 2006, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists published a similar advisory (10) . After these warnings were publicized in the media, a web site was developed that invited women to join a class action suit against GlaxoSmithKline if they had taken paroxetine in pregnancy and delivered a baby with a cardiovascular birth defect (11) .

We were concerned that, because 50% of pregnancies are unplanned (12) , women who were already pregnant and taking paroxetine might abruptly discontinue their medication. Abrupt discontinuation is generally not wise, although some women may feel that it is the right course to take (13) . Notably, there have been no similar warnings about the risk of cardiovascular birth defects from the psychiatric professional bodies. In a study of 201 pregnant women recently published by a group of psychiatrists (14) , 86 (43%) women experienced a relapse of major depression during pregnancy. Among the 82 women who maintained their medication throughout their pregnancy, 21 (26%) relapsed, compared with 44 (68%) of the 65 women who discontinued medication. The authors noted that women with a history of depression were less likely to relapse if they stayed on their medication during pregnancy and recommended that each case be considered individually.

The primary objective of our study was to collect from teratology information services around the world as many cases as possible of infants who had first-trimester in utero exposure to paroxetine and to calculate the rate of cardiovascular defects in these infants and in a unexposed cohort. The secondary objective was to contact the authors of database studies that had been published on antidepressants as a class to determine how many women in these studies had been exposed to paroxetine and the rates of cardiovascular defects in their infants.

Method

We identified pregnancy outcomes of infants exposed in utero to paroxetine from two sources: teratology information services and database studies. The Motherisk Program at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto is a teratology information service. We provide evidence-based information on the safety of and risks associated with exposures to drugs, chemicals, radiation, and infectious diseases during pregnancy and lactation to pregnant women, lactating mothers, and their health care providers. We also conduct observational studies of drugs and other exposures in pregnancy. We are a member of the Organization of Teratology Information Services (OTIS), a group with members in North America. The European Network of Teratology Information Services (ENTIS) is a group based in Europe, and similar services operate in other parts of the world, providing services similar to those we provide and collecting information on women and pregnancy outcomes in the same fashion. We have collaborated on many occasions, including in research on pregnancy outcomes of women who were exposed to various antidepressants (15 – 20) .

At the teratology information services, women are recruited for studies when they call to inquire about the use of a drug they are taking and are currently pregnant. Eligible women are prospectively enrolled in the study after providing informed consent over the telephone. During the initial telephone contact, demographic information, medical and obstetrical histories, and details of exposure and concurrent exposures are recorded on a standardized questionnaire form. Details about the exposure include duration, timing in pregnancy, dose, frequency, and medical indication for use of the drug. Women are informed that they will be contacted after their expected date of delivery for an assessment of pregnancy outcome. At the follow-up interview, gestational findings and fetal outcomes are documented on a structured, standardized form by telephone interview. With the mother’s permission, this report is corroborated with the report of the physician caring for the baby.

This method of data collection by teratology information services involves three critical elements that are not always possible with database studies: personal interviews with the mothers; confirmation of drug exposure, including time and dose; and confirmation of the congenital defect by the child’s attending physician. In addition, because all of the women called the teratology information service when they were in early pregnancy and the details of their pregnancy and drug exposure were recorded at that time, the possibility of recall bias is eliminated.

We contacted members of OTIS, ENTIS, and the other services to request available pregnancy outcomes of women who had taken paroxetine in the first trimester of pregnancy. We requested details of their cases, with specific information on the rates of cardiovascular defects and ascertainment of the infant’s age at the time of diagnosis. To form a comparison group, we obtained an equal number of pregnancy outcomes of other women who called teratology information services inquiring about exposures to drugs that are considered safe in pregnancy, such as acetaminophen, and calculated the rate of cardiovascular defects in infants of mothers in this group. Women in the comparison group had similar demographic and clinical characteristics to those of the study group, such as smoking, alcohol use, and socioeconomic status, and their infants were not exposed to teratogenic agents or antidepressants. They were not enrolled in any other study.

Subsequently, we identified published database studies of pregnancy outcomes following exposure to antidepressants. Since all of these studies presented SSRI data aggregated by class (21 – 24) , we contacted the authors and requested the same information, specific to paroxetine, as we had from the teratology information services.

The rate of cardiovascular birth defects following exposure to paroxetine in pregnancy was compared with the rate in the comparison group of unexposed women by means of chi-square test and expressed as an odds ratio as well as in percentages.

The study protocol was approved by the Hospital for Sick Children Research Ethics Board as well as by the research ethics boards at the other sites.

Results

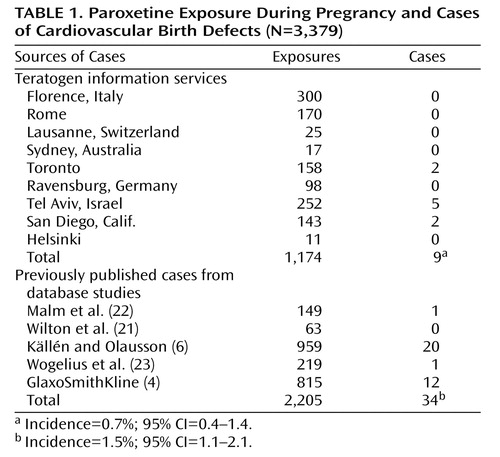

We were able to ascertain 1,174 unpublished cases of first-trimester paroxetine exposure from eight teratology information services and 2,061 cases from five previously published database studies, including the GlaxoSmithKline study (4) ( Table 1 ). One of the groups of authors we contacted to request information from their database (24) was not able to provide details of specific exposure to paroxetine because of the confidentiality policy of the database (although the authors did report that there were 320 cases of women exposed to paroxetine in their study).

All of the women in the cases we ascertained had been taking paroxetine before they became pregnant and continued well into the first trimester, so their infants were exposed while the fetal heart was developing.

The rates of cardiovascular defects in the teratology information service cohort were 0.7% in the exposed group and 0.7% in the unexposed group (odds ratio=1.1, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.36–2.78). In the database group, the rate was 1.5%. When the data sets from the teratology information services and from the database studies were combined, the mean rate of cardiovascular defects was 1.2% (95% CI=1.1–2.1).

Discussion

To our knowledge, these data represent the largest documented number of exposures (>3,000) to paroxetine during the first trimester of pregnancy. The rate of cardiovascular defects falls well within the incidence of cardiovascular defects in the general population, which was documented in Hoffman and Kaplan’s landmark study investigating the incidence of congenital heart disease in the population (25) . Hoffman and Kaplan reviewed 62 studies published since 1955 in an attempt to determine the reasons for the variability of the reported incidence of congenital heart disease. After taking into account the timing of diagnosis, their estimate of the incidence of moderate and severe forms of cardiovascular defects was about 6 per 1,000 live births, which increases to 19 per 1,000 with the inclusion of the potentially serious bicuspid aortic valve, and to 75 per 1,000 with the inclusion of tiny muscular ventricular septal defects that are present at birth and may resolve spontaneously and other trivial lesions. Their estimate of the overall incidence was 0.96% (95% CI=0.7–1.2). They also concluded that there is no evidence for differences in incidence among different countries.

Confirmation of the timing of diagnosis was not standardized in either the teratology information services or the database studies, and the timing varied from 1 month to 3 years of age across all studies. Consequently, some defects would not have been detected immediately after birth in the early interviews, and conversely, some would have resolved spontaneously by the time of the later examinations. Källén and Olausson (6) , who reported the highest incidence, did state that most of the defects in their cohort were minor, and in a personal communication (January 2007) Källén indicated that his group counted all diagnosed cardiovascular defects, even if they resolved spontaneously. In contrast, the teratology information service groups did not include cardiovascular defects that resolved spontaneously (with the exception of Diav-Citrin et al. [7] , who reported a higher rate; personal communication, December 2006), so this would account for their lower rates. The GlaxoSmithKline results did not specify whether the defects were mild, moderate, or severe, so a number of these cases may have resolved spontaneously, and inclusion of these cases could have inflated the rate. However, despite these discrepancies and variations, the overall rate still fell within the limits described in Hoffman and Kaplan’s report on population rates of cardiovascular defects (25) .

Our study has several limitations. One of these is the sample size, which is relatively small for an epidemiologic study. However, to date the cases we report on constitute the largest number of prospectively ascertained pregnancy outcomes after exposure to paroxetine, including the database studies. If, as reported in the Hoffman and Kaplan review (25) , cardiovascular defects occur in approximately 1% of cases, our sample size is large enough to rule out a twofold increased risk. Another limitation may be the combining of cases from different countries. However, as documented in our previous publications, when maternal characteristics were compared among sites, we found no differences (17 , 20) . Women who call teratology information services anywhere in the world tend to be more highly educated, of higher socioeconomic status, and older, with a mean age of 30 years (SD=2). They do not reflect all pregnant women in the general population who use antidepressants, but as a group they are homogeneous. For obvious reasons, it is impossible to conduct a randomized controlled study of women taking drugs during pregnancy.

A recent study by Berard et al. (26) reported an increased risk of cardiac defects (1.7%) associated with paroxetine, but only with dosages above 25 mg/day. In our study, most of the women received paroxetine at a dosage of 20 mg/day or less, and there was not enough variability to conduct a dose-response analysis. The Berard et al. study is the first to report a dose response, although it was based on information from a prescription database, which lacks any confirmation that the women actually took the medication as dispensed. It is conceivable that women stopped taking paroxetine when their pregnancy was diagnosed, or lowered the dose, especially after seeing media reports of concerns about paroxetine use in pregnancy. We reported this phenomenon in a recent publication based on interviews of women after reports in the media of concerns regarding neonatal effects of antidepressants (27) .

In summary, our data suggest that paroxetine is not associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular birth defects. The number of cases in our analysis is larger than in other published studies on this topic, which typically have sample sizes in the range of 100–200 cases (17 , 19) . With nearly 1,200 cases from teratology information services and over 2,200 cases from previously published database studies, our findings may be considered sufficient evidence to suggest that there is no association between the use of paroxetine in pregnancy and risk of cardiovascular defects in exposed infants.

This is important information for women and their health care providers in their effort to make informed, evidence-based decisions as to whether to take paroxetine during pregnancy. Untreated depression during pregnancy appears to carry substantial perinatal risks, whether they be direct risks to the fetus and infant or risks secondary to unhealthy maternal behaviors arising from depression. These risks include suicidal ideation, an increased risk of miscarriage, hypertension, preeclampsia, and lower birth weight. Moreover, untreated depression in pregnancy is associated with a sixfold increase in the risk of postpartum depression (28 , 29) . Consequently, appropriate treatment of depression during pregnancy is essential, and if this includes taking paroxetine, the findings of this study should reassure women and their health care providers. A pregnant woman should always be in the best mental health possible to ensure optimal outcomes for herself and her child.

1. Einarson TR, Einarson A: Newer antidepressants in pregnancy and rates of major malformations: a meta-analysis of prospective comparative studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2005; 14:823–827Google Scholar

2. Wen SW, Yang Q, Garner P, Fraser W, Olatunbosun O, Nimrod C, Walker M: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006; 194:961–966Google Scholar

3. Malm H, Klaukka T, Neuvonen PJ: Risks associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2005; 106:1289–1296Google Scholar

4. GlaxoSmithKline: Epidemiology study: paroxetine in the first trimester and the prevalence of congenital malformations. http://ctr.gsk.co.uk/Summary/paroxetine/studylist.aspGoogle Scholar

5. Cole JA, Ephross SA, Cosmatos IS, Walker AM: Paroxetine in the first trimester and the prevalence of congenital malformations. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007; 16:1075–1085Google Scholar

6. Källén BA, Olausson P: Maternal use of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors in early pregnancy and infant congenital malformations. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2007; 79:301–308Google Scholar

7. Diav-Citrin O, Shechtman S, Weinbaum D, Arnon J, Di Gianantonio E, Clementi M, Ornoy A: Paroxetine and fluoxetine in pregnancy: controlled study (abstract). Reprod Toxicol 2005; 20:459Google Scholar

8. Health Canada: Public advisory: Health Canada endorsed important safety information on Paxil (paroxetine), Oct 6, 2005. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/medeff/advisories-avis/public/2005/paxil_3_pa-ap_e.htmlGoogle Scholar

9. US Food and Drug Administration: FDA Public Health Advisory: Paroxetine. Dec 8, 2005. http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/advisory/paroxetine200512.htmGoogle Scholar

10. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee on Obstetric Practice: ACOG Committee Opinion No 354: Treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 108:1601–1603Google Scholar

11. Paxil, pregnancy, and birth defects. Nov 9, 2006. www.lawyersandsettlements.com/articles/paxil-pregnancy-birth-defectsGoogle Scholar

12. Finer LB, Henshaw SK: Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2006; 38:90–96Google Scholar

13. Einarson A, Selby P, Koren G: Abrupt discontinuation of psychotropic drugs during pregnancy: fear of teratogenic risk and impact of counselling. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2001; 26:44–48Google Scholar

14. Cohen LS, Altshuler LL, Harlow BL, Nonacs R, Newport DJ, Viguera AC, Suri R, Burt VK, Hendrick V, Reminick AM, Loughead A, Vitonis AF, Stowe ZN: Relapse of major depression during pregnancy in women who maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment. JAMA 2006; 295:499–507Google Scholar

15. Pastuszak A, Schick-Boschetto B, Zuber C, Feldkamp M, Pinelli M, Donnenfeld A, McCormak M, Leen-Mitchell M, Woodland C, Gardner A, Hom M, Koren G: Pregnancy outcome following first trimester exposure to fluoxetine. JAMA 1993; 269:2246–2248Google Scholar

16. Kulin NA, Pastuszak A, Sage SR, Schick-Boschetto B, Spivey G, Feldkamp M, Ormond K, Matsui D, Stein-Schechman AK, Cook L, Brochu J, Rieder M, Koren G: Pregnancy outcome following maternal use of the new selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a prospective controlled multicenter study. JAMA 1998; 279:609–610Google Scholar

17. Einarson A, Fatoye B, Sarkar M, Lavigne SV, Brochu J, Chambers C, Mastroiacovo Po, Addis A, Matsui D, Schuler L, Einarson TR, Koren G: Pregnancy outcome following gestational exposure to venlafaxine: a multicenter prospective controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1728–1730Google Scholar

18. Einarson A, Bonari L, Voyer-Lavigne S, Addis A, Matsui D, Johnson Y, Koren G: A multicentre prospective controlled study to determine the safety of trazodone and nefazodone use during pregnancy. Can J Psychiatry 2003; 48:106–110Google Scholar

19. Chun-Fai-Chan B, Koren G, Fayez I, Kalra S, Voyer-Lavigne S, Boshier A, Shakir S, Einarson A: Pregnancy outcome of women exposed to bupropion during pregnancy: a prospective comparative study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 192:932–936Google Scholar

20. Djulus J, Koren G, Einarson TR, Wilton L, Shakir S, Diav-Citrin O, Kennedy D, Voyer Lavigne S, De Santis M, Einarson A: Exposure to mirtazapine during pregnancy: a prospective, comparative study of birth outcomes. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67:1280–1284Google Scholar

21. Wilton LV, Pearce GL, Martin RM, Mackay FJ, Mann RD: The outcomes of pregnancy in women exposed to newly marketed drugs in general practice in England. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998; 105:882–889Google Scholar

22. Malm H, Klaukka T, Neuvonen PJ: Risks associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2005; 106:1289–1296Google Scholar

23. Wogelius P, Norgaard M, Gislum M, Pedersen L, Munk E, Mortensen PB, Lipworth L, Sorensen HT: Maternal use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of congenital malformations. Epidemiology 2006; 17:701–704Google Scholar

24. Wen SW, Yang Q, Garner P, Fraser W, Olatunbosun O, Nimrod C, Walker M: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006; 194:961–966Google Scholar

25. Hoffman JI, Kaplan S: The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:1890–1900Google Scholar

26. Berard A, Ramos E, Rey E, Blais L, St-Andre M, Oraichi D: First trimester exposure to paroxetine and risk of cardiac malformations in infants: the importance of dosage. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol 2007; 80:18–27Google Scholar

27. Einarson A, Schachtschneider AK, Halil R, Bollano E, Koren G: SSRI’s and other antidepressant use during pregnancy and potential neonatal adverse effects: impact of a public health advisory and subsequent reports in the news media. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2005; 5:11Google Scholar

28. Bonari L, Pinto N, Ahn E, Einarson A, Steiner M, Koren G: Perinatal risks of untreated depression during pregnancy. Can J Psychiatry 2004; 49:726–735Google Scholar

29. Beck CT, Records K, Rice M: Further development of the Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory—Revised. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2006; 35:735–745Google Scholar