Impact of Clinical Training on Violence Risk Assessment

Mr. A, a 46-year-old man, requests evaluation of possible depression. He reports stressors including marital separation, unemployment, and limitation of his visits with his children. He has been tense, sad, angry, and unable to sleep, eat, or relax and has had racing and occasionally suicidal and homicidal thoughts. He expresses a desire to feel better and to reconcile with his wife. He previously has been given a variety of medication regimens that he discontinued because of a perceived lack of efficacy and intolerable side effects. He acknowledges a long history of infidelity and domestic violence toward his wife. He assaulted one of his parents as an adolescent and has been in physical fights with others as an adolescent and an adult. He was unable to complete school because of his behavior. He lives alone and spends his days surfing the Internet and pacing in his home. He owns several guns. Mr. A is cooperative during the interview but appears tense, frequently clenching his fists and sighing in an exasperated way. His thoughts are organized in a linear and goal-directed manner. He denies hallucinations, delusions, or current homicidal or suicidal ideation. This article addresses whether training psychiatric residents and clinical psychology interns in evidence-based risk assessment can enhance their documentation of assessment and management of patients’ risk of violence.

The assessment and management of the risk of violence are core issues at the interface of law and mental health. Legislation and case law establish many contexts in which mental health clinicians are expected to have basic competence in risk assessment (1) . For example, clinicians are expected to be able to assess whether intervention is needed to protect third parties from patients’ violence, to assess when patients pose a sufficient level of risk to justify involuntary civil commitment, and to assess when patients who have been hospitalized can be safely discharged to the community. Adverse outcomes associated with carrying out these risk assessments can expose clinicians to malpractice liability.

However, surveys of practitioners suggest that many receive little formal training in violence risk assessment. Schwartz and Park (2) surveyed a national sample of 517 psychiatric residents and reported that a third of the respondents received no training in assessing and managing patients’ risk of violence, and a third described their training as inadequate. Guy et al. (3) reported that the 340 psychologists in their national sample had a median of zero hours of formal training in the assessment and management of patient violence.

The limitations of formal training in risk assessment for violence suggested by such surveys underscore the need for education in this topic, which has been endorsed by professional groups such as a Task Force on Clinician Safety of APA (4) and a Task Force on Education and Training in Behavioral Emergencies of the American Psychological Association (5) . However, little research has been published on models for such training or on their impact.

Given the many advances in the science of risk assessment that have occurred in the last 15 years, there is particular need for demonstration that the scientific knowledge base can be translated into skills that can be learned by practitioners. A variety of structured risk assessment tools have been developed that have promise for improving decision making about potentially violent patients (e.g., references 6 – 9 ). Monahan (10) has pointed out that in many situations the clinician is the person who is both assessing violence risk and making decisions about its management. From the perspective of exposure to liability, a core component of the risk assessment process is documentation that makes explicit the information gathered and considered by the clinician and the rationale for the actions taken.

We evaluated a systematic training program in evidence-based violence risk assessment by comparing trainees in psychiatry and psychology who received the training with similar trainees who did not. We examined changes in risk assessment skill associated with the training based on clinical documentation composed in response to case vignettes as well as changes in self-evaluation of competence in risk assessment. The protocol was approved by the Committee on Human Research of the University of California, San Francisco. The participants gave informed consent to participate in the anonymous evaluation of the training.

Participants in the Training Program

The risk assessment training group participants consisted of 45 trainees who attended either of two occasions on which a workshop on risk assessment was offered to clinicians in a university-based psychiatry department: 43 were residents in psychiatry (15 in the first postgraduate year, 22 in the second postgraduate year, and six in the third postgraduate year), and two were clinical psychology interns.

The comparison group participants consisted of 10 residents in psychiatry in the first postgraduate year who attended a 3-hour workshop on the application of evidence-based medicine to psychiatry that was not focused specifically on risk assessment for violence.

Description of Training in Risk Assessment for Violence

The training consisted of a 5-hour workshop on evidence-based assessment and management of risk of violence and suicide. The focus of this article is the component concerning violence risk. The workshop was led by 12 faculty psychiatrists and psychologists. Workshop leaders included the chairman of the medical school department of psychiatry and clinical leaders from the various clinical services in the hospital. The content of the workshop included the following:

1. Pretest

Before the training, the participants completed a questionnaire about their education, training, experience, and perceived competence in risk assessment. In addition, the participants responded to a clinical vignette about a patient by writing a progress note that included a summary of the assessment and plan regarding the patient’s imminent risk of violence. A summary of a sample vignette is presented at the beginning of this article.

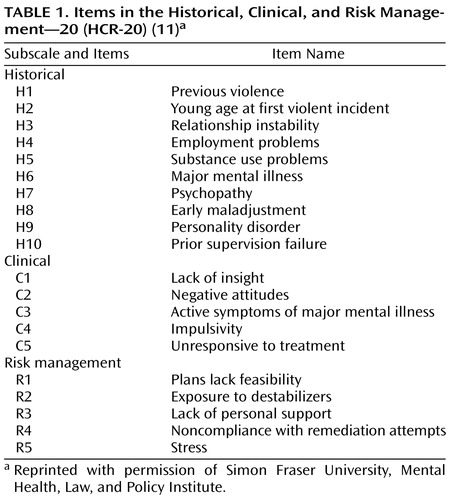

2. Didactic Presentation: Risk Factors

The participants received a 1-hour lecture on assessment and management of violence risk that was organized based on the Historical, Clinical, and Risk Management—20 (HCR-20) (11) and associated constructs (12 , 13) . This approach, referred to as structured professional judgment, represents clinical guidelines to assist decision making about risk. The approach uses a memory aid that prompts the clinician to consider information about core risk factors that the scientific and professional literature suggests need to be considered in a reasonably comprehensive risk assessment. The items in the HCR-20 are listed in Table 1. The items in the risk assessment tool are not weighted or combined in a formula to arrive at a risk estimate; the clinician uses judgment in determining whether the risk is low, moderate, or high and develops a risk management plan based on the level of assessed risk.

3. Small Group Discussion

Attendees participated in small groups of four to eight participants, facilitated by faculty members. The small groups were provided with two additional case vignettes and were asked to identify historical, clinical, and risk management factors in each vignette; to envision scenarios that would affect the patients’ level of risk; to estimate the patients’ level of risk; and to develop intervention plans appropriate to that risk level.

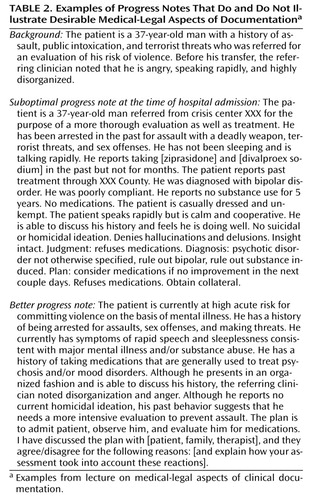

4. Didactic Presentation: Medical-Legal Aspects of Clinical Documentation

The participants received an hour-long lecture on documentation of risk. The content was based on the widely endorsed model of 1) gathering information about risk and protective factors, 2) rationally weighing those factors to formulate the level of risk, 3) based on the assessed risk, developing and implementing a plan of intervention to reduce the risk, and 4) documenting this process (cf., references 10 , 13 – 15 ). Table 2 illustrates examples that were presented of progress notes that do and do not follow these principles.

5. Posttest

After the training, the participants again completed questions about their perceived knowledge and competence in various components of risk assessment. In addition, they wrote a second progress note, based on a clinical vignette about a different patient, that included a summary of the assessment and plan regarding the patient’s imminent risk of violence.

The order of the two clinical vignettes was counterbalanced so that approximately half of the risk assessment training group participants had one vignette as the pretest and the other vignette as the posttest; the other half of the participants received the vignettes in reverse order.

Comparison Group

The comparison group participants responded to the same pretest and posttest questionnaires and vignettes as those who received the risk assessment training. As with the training group, the order of the pretest and posttest vignettes was counterbalanced.

Measures to Assess the Results of Training

Content Analysis of Progress Notes Written in Response to Vignettes

The progress notes based on the case vignettes were independently rated by two clinicians (a senior psychiatrist, S.E.H, and one of two advanced clinical psychology fellows, C.M.W. or S.R.F.) who were blind to whether the notes were pretests or posttests. The ratings included three major dimensions:

1. Analysis of 20 indicators of documentation quality: The raters used a structured content analysis including 20 variables based on the literature on the standard of care in violence risk assessment (e.g., references 10 , 14 , and 15 ) and dimensions derived from an earlier pilot version of the training that had been given to a different group of workshop participants. The ratings included identification of specific risk and protective factors, explanation of the thought process in decision making about risk level (i.e., articulation of rational weighing of the risk factors and protective factors in developing a risk assessment and a plan of intervention), and organization of thinking about risk management, e.g., why particular risk management plans were selected and alternatives were rejected. Each item was rated on a scale of 0 (item absent), 1 (item possibly present), or 2 (item present). For the purposes of data analysis, we computed a composite score consisting of the sum of the individual items.

2. Global rating of quality of progress note: The raters coded the overall quality of the documentation concerning risk assessment for violence on a scale ranging from 1 (poor) to 7 (excellent).

3. Estimate of whether progress note was written before or after training in risk assessment: The raters made an estimate on a 7-point scale concerning whether the progress note had been written before or after the risk assessment training.

Interrater reliability between the two coders was measured with the average intraclass correlation coefficient, which was r=0.93 for the composite score of the ratings of 20 indicators of documentation quality, r=0.86 for the global quality of the progress note, and r=0.75 for whether the progress note had been completed before or after training in risk assessment. Data analyses are based on the average of the ratings of the two coders.

Self-Assessment of Competence

Before and after each workshop, participants in both the risk assessment training group and the comparison group rated items on a 7-point scale concerning their ability to accurately assess patients’ risk of violence, their ability to manage patients’ risk of violence, and their knowledge about violence and working with violent patients.

Data Analysis

To determine the extent to which participation in risk assessment training accounted for changes in documentation, we used multiple regression analysis in which we evaluated models that included the pretest score, a dummy variable indicating the order of presentation of the vignettes, and whether or not the participant had received the risk assessment training. In each case, the dependent variable was a change score that assessed the extent to which the posttest score differed from the pretest score. We calculated Cohen’s f 2 to determine the effect size of adding the variable representing whether or not the participants received risk assessment training compared to models including only the pretest score and the order of presentation of the vignettes (16) . By convention, f 2 values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35, respectively, are considered small, medium, and large effect sizes (17) .

We used a similar data analytic strategy to evaluate the extent to which the risk assessment training accounted for changes in self-rated competence in risk assessment.

Baseline Level of Training and Experience

The risk assessment training participants did not differ significantly from the comparison group participants in the number of hours of prior formal training in assessing and managing violence risk (mean=5.0, SD=6.5, and mean=1.7, SD=1.7, respectively) (t=–1.60, df=53, n.s.). The two groups did not differ significantly in the number of potentially violent patients worked with previously. Of the risk assessment training participants and the comparison group participants, respectively, 16% (seven of 45) and 20% (two of 10) had worked with less than six potentially violent patients, 36% (16 of 45) and 20% (two of 10) had worked with six to 20 such patients, and 49% (22 of 45) and 60% (six of 10) had worked with more than 20 such patients (χ 2 =0.90, df=2, n.s.). At baseline, participants in the risk assessment training did not differ significantly from those in the comparison group in self-rated ability to accurately assess patients’ risk of violence on a scale ranging from 1 (completely unable) to 7 (completely able) (mean=4.2, SD=1.1, and mean=3.9, SD=1.1, respectively) (t=–0.72, df=53, n.s.). The two groups did differ, however, at baseline in general clinical experience. The participants in the risk assessment workshop reported significantly more years of previous experience providing mental health services than the comparison group participants (mean=2.0, SD=2.1, and mean=0.6, SD=0.6, respectively) (t=–2.17, df=53, p<0.04).

Objective Changes in Quality of Documentation

Summary Score of 20 Characteristics Recommended in the Literature for Documentation About Violence Risk

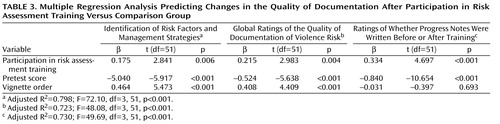

Table 3 shows the results of multiple regression analyses that controlled for pretest scores and order of presentation of the vignettes. The participants in the risk assessment training group improved significantly more than the comparison group participants in their ability to identify risk and protective factors for violence and in their ability to articulate better-organized reasoning about risk assessment and risk management strategies (b=0.175, p<0.01). The size of the effect of risk assessment training on improvement in clinical progress notes based on 20 specific characteristics recommended in the literature on documentation about violence risk was medium ( f 2 =0.16).

Global Ratings of Quality of Progress Notes

Table 3 shows that in analyses that controlled for baseline skill (as measured by the pretest score) and the order of presentation of the vignettes, the participants who received the risk assessment training demonstrated significantly more improvement in the overall quality of their documentation concerning violence risk assessment compared to those who did not receive the training (b=0.215, p<0.001). The size of the effect of the risk assessment training on improvement in the overall quality of the progress notes was medium ( f 2 =0.18).

Ratings of Whether the Progress Notes Were Written Before or After Training

As shown in Table 3 , the effect of receiving the risk assessment training on independent ratings of how likely it was that the writer of the progress note had received this training was significant (β=0.334, p<0.001). The size of the effect of participating in the risk assessment training on change in the likelihood that the note was rated as being after the training was large ( f 2 =0.43).

The control variables (order of presentation of the vignettes and the pretest score) also predicted the outcome measures. Vignette order accounts for variability in the stimuli used to measure risk assessment skill. The pretest score is an indicator of baseline skill in risk assessment. The participants with lower baseline skill showed greater change on the outcome measures.

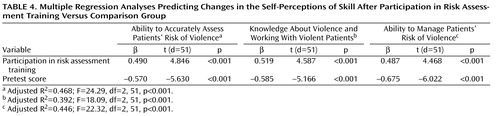

Change in Self-Assessment of Competence

As shown in Table 4 , the results of multiple regression analyses that controlled for the level of self-rated competence at pretest showed statistically significant and large effect sizes for the effect of participation in the risk assessment training on increases in self-ratings of the ability to assess patients’ risk of violence ( f 2 =0.46), knowledge about violence and working with violent patients ( f 2 =0.41), and the ability to manage patients’ violence ( f 2 =0.39). Table 4 also shows that participants who rated their competence in risk assessment as lower at pretest showed greater increases in self-rated skills.

Perspective on the Impact of Training

These findings suggest that systematic training in evidence-based violence risk assessment leads to objective improvements in clinical documentation as measured by independent raters, with progress notes written after the risk assessment training demonstrating more systematic consideration of historical, clinical, and risk management variables that pertain to violence risk as well as more explicit analysis of the significance of these risk factors for interventions to reduce patients’ risk of violence. Clinicians appear to be able to better articulate the rationale for their risk assessments and risk management plans after receiving specific training in this area. The improvement in the quality of documentation shown by the participants in the risk assessment training was substantial relative to a comparison group who participated in more general training in evidence-based practice. The effect of risk assessment training on improvement in clinical documentation held up in multivariate analyses that controlled for the participants’ baseline skill and for variability of the vignettes used to measure their ability to formulate violence risk assessments in writing.

Participation in training also was associated with enhanced self-confidence in risk assessment skill. Although self-perceptions of skill may be affected by demand characteristics inherent in the context of evaluating the workshop, it is of interest that the participants in the training showed increases in self-rated competence that mirrored the objective improvements in risk assessment skill.

The extent to which clinical progress notes with actual patients will demonstrate improvements similar to those that we observed in response to the case vignettes remains to be determined. However, actual patients vary in the degree to which they have risk and protective factors for violence, and therefore, instructors who provide training in risk assessment will need to consider the clinical state of the patient in evaluating such notes. The design of the present study controlled for this source of variability by using standard case vignettes, simplifying interpretation of changes in documentation as being due to the effect of training. The results of this study suggest that training in evidence-based risk assessment enhances case formulations so that they are more transparent and in accord with the literature on the assessment and management of the risk of violence.

1. McNiel DE, Borum R, Douglas KS, Hart SD, Lyon D, Sullivan LE, Hemphill JF: Risk assessment, in Taking Psychology and Law into the 21st Century: Reviewing the Discipline—A Bridge to the Future. Edited by Ogloff JRP. New York, Plenum, 2002, pp 147–170Google Scholar

2. Schwartz TL, Park TL: Assaults by patients on psychiatric residents: a survey and training recommendations. Psychiatr Serv 1999; 50:381–383Google Scholar

3. Guy JD, Brown CK, Poelstra PL: Who gets attacked? a national survey of patient violence directed at psychologists in clinical practice. Prof Psychol: Res Pract 1990; 21:493–495Google Scholar

4. Dubin WR, Lion JR (eds): Clinician Safety: Report of the American Psychiatric Association Task Force on Clinician Safety. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

5. American Psychological Association, division 12, section VII: Task Force Report on Education and Training in Behavioral Emergencies. http://www.apa.org/divisions/div 12/sections/section 7/tfreport.html, 2000Google Scholar

6. Douglas KS, Ogloff JRP, Hart SD: Evaluation of a model of violence risk assessment among forensic psychiatric patients. Psychiatr Serv 2003; 54:1372–1379Google Scholar

7. Monahan J, Steadman HJ, Robbins PC, Appelbaum P, Banks S, Grisso T, Heilbrun K, Mulvey EP, Roth L, Silver E: An actuarial model of violence risk assessment for persons with mental disorders. Psychiatr Serv 2005; 56:810–815Google Scholar

8. Hilton NZ, Harris GT, Rice ME, Lang C, Cormier CA, Lines KJ: A brief actuarial assessment for the prediction of wife assault recidivism: the Ontario Domestic Assault Risk Assessment. Psychol Assess 2004; 16:267–275Google Scholar

9. McNiel DE, Gregory AL, Lam JN, Binder RL, Sullivan GR: Utility of decision support tools for assessing acute risk of violence. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003; 71:945–953Google Scholar

10. Monahan J: Limiting therapist exposure to Tarasoff liability: guidelines for risk containment. Am Psychol 1993; 48:242–250 Google Scholar

11. Webster CD, Douglas KS, Eaves D, Hart SD: HCR-20: Assessing Risk for Violence (version 2). Burnaby, B.C., Canada, Simon Fraser University, Mental Health, Law, and Policy Institute, 1997Google Scholar

12. Hart SD: Assessing and managing violence risk, in HCR-20 Violence Risk Management Companion Guide. Edited by Douglas KS, Webster CD, Hart SD, Eaves D, Ogloff JRP. Burnaby, B.C., Canada, Simon Fraser University, Mental Health, Law, and Policy Institute, 2001, pp 13–25Google Scholar

13. McNiel DE: Assessment and management of acute risk of violence in adults, in Evaluating and Managing Behavioral Emergencies: An Evidence-Based Resource for the Mental Health Practitioner. Edited by Kleespies PA. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association (in press)Google Scholar

14. Gutheil TG, Appelbaum PD: Clinical Handbook of Psychiatry and the Law, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins, 2000Google Scholar

15. Simon RL: Commentary: think fast, act quickly, and document (maybe). J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2003; 31:65–67Google Scholar

16. Cohen J, Cohen P: Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1983Google Scholar

17. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1988Google Scholar