A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Memantine in the Treatment of Major Depression

Abstract

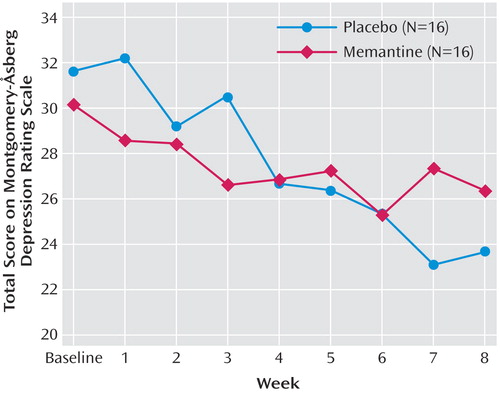

OBJECTIVE: This study was designed to assess possible antidepressant effects of memantine, a selective N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist in humans. METHOD: In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 32 subjects with major depression were randomly assigned to receive memantine (5–20 mg/day) (N=16) or placebo (N=16) for 8 weeks. Primary efficacy was assessed by performance on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). RESULTS: The linear mixed models for total MADRS scores showed no treatment effect. CONCLUSIONS: In an 8-week trial, the low-to-moderate-affinity NMDA antagonist memantine in doses of 5–20 mg/day was not effective in the treatment of major depressive disorder.

Increasing evidence suggests that the glutamatergic system may be involved in the pathophysiology and treatment of depression. This includes the delayed, indirect effects of many antidepressants on the glutamatergic system, as well as the antidepressant effects of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists in animal models of depression and glutamatergic modulators in humans (reviewed in reference 1). However, it remains unclear what aspects of glutamatergic modulation are necessary for antidepressant effects to occur (i.e., direct inhibition of the release of glutamate, direct effects at the ionotropic [NMDA, AMPA] or metabotropic receptors, or some combination of these mechanisms). In this context, it is noteworthy that a series of candidate glutamatergic drugs are available for human use; these agents allow for a more precise dissection of the role of the glutamatergic system in mood disorders (1).

We first tested the glutamatergic modulator riluzole (an inhibitor of glutamate release) and found it to have antidepressant properties in patients with treatment-resistant major depression (2) and bipolar depression (3). In the present study, we sought to determine if selective antagonism of the NMDA receptor alone produces antidepressant effects. Berman et al. (4) found that a single dose of the high-affinity NMDA receptor antagonist ketamine resulted in a rapid—albeit transitory—antidepressant effect in patients with major depression. Unfortunately, ketamine’s psychotomimetic effects preclude its use as a chronic antidepressant. Memantine is a low-to-moderate-affinity noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist (5) that is currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. In contrast to ketamine, memantine is devoid of psychotomimetic effects at therapeutic doses (5–20 mg/day) (5).

The objective of this study was to examine in a controlled study the efficacy and safety of the selective NMDA antagonist memantine in the treatment of major depression.

Method

Men and women 18 to 80 years old who were outpatients with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, recurrent, without psychotic features, diagnosed according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, were eligible to participate in the study. Subjects were required to have a Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score of ≥22 at screening and at the start of medication treatment (baseline).

The patients included in the study had been free of comorbid substance abuse or dependence for 3 months, were free of acute medical illnesses, and were judged clinically not to be at serious risk for suicide. Comorbid axis I anxiety disorder diagnoses were permitted. The study was approved by the National Institute of Mental Health Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients after the procedures had been fully explained.

Patients were evaluated on a weekly basis with the MADRS (primary efficacy measure), the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity scale, and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A). After a 2-week single-blind placebo lead-in phase and drug-free period, participants were randomly assigned to double-blind treatment with memantine or placebo for 8 weeks. Subjects with a decrease of more than 20% in MADRS score during the 2-week drug-free period were excluded. Memantine was started at 5 mg/day and increased by 5 mg/week as tolerated up to a maximum of 20 mg/day. Zolpidem 5–10 mg/day was given as needed for insomnia (no more than three times per week) but not within 8 hours of ratings. No other psychotropic medication was allowed. Clinical response was defined as a decrease of 50% or greater in MADRS score from baseline. No structured psychotherapy was permitted during the trial. Treatment compliance was monitored by capsule counts.

Linear mixed models were used to evaluate changes in MADRS, CGI severity scale, and HAM-A scores. Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate categorical outcomes.

Results

Thirty-two patients (16 men, 16 women; mean age=46.6 years, SD=10.8) were randomly assigned to receive memantine (N=16) or placebo (N=16). Eight subjects did not complete the placebo lead-in phase because of noncompliance with research procedures (N=4), significant worsening of depression (N=1), or an improvement of more than 20% in MADRS scores (N=3). One subject with early Alzheimer’s disease who had a long history of major depressive disorder before the onset of the dementing process was included. Completion rates were 81% (N=13) for memantine and 81% (N=13) for placebo. Noncompletion in the memantine group was attributed to worsening at weeks 3 and 4 (N=2) and an adverse event at week 7 (N=1). Noncompletion in the placebo group was attributed to worsening at week 3 (N=1), an adverse event at week 3 (N=1), and withdrawal of consent at week 2 (N=1).

There were no significant differences between the two groups in age (memantine: mean=47.1 years, SD=12.3; placebo: mean=46.1 years, SD=9.4), number of women in the group (memantine: N=9 [56%]; placebo: N=7 [44%]), current comorbid anxiety disorder (memantine: N=3 [19%]; placebo: N=2 [13%]), taking antidepressants at the time of screening (memantine: N=4 [25%]; placebo: N=3 [19%]), or previous failure to respond to an adequate antidepressant trial (memantine: N=4 [25%]; placebo: N=3 [19%]). Patients received memantine at a mean dose of 19.4 mg/day (SD=2.5) (15 [94%] patients achieved 20 mg/day) for a mean duration of 7.4 weeks (SD=1.5). Only four subjects took zolpidem as needed (two in the memantine group and two in the placebo group).

The linear mixed models for total MADRS, CGI severity scale, and HAM-A scores showed no treatment effect (MADRS: F=0.01, df=1, 31, p=0.91 [Figure 1]; CGI severity scale: F=0.05, df=1, 32, p=0.82; HAM-A: F=0.42, df=1, 33, p=0.52) or interaction (MADRS: F=0.22, df=8, 141, p=0.11; CGI severity scale: F=0.96, df=8, 140, p=0.47; HAM-A: F=0.84, df=8, 117, p=0.57).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial of a selective NMDA antagonist in the treatment of major depressive disorder. This study failed to show that memantine, a low-to-moderate-affinity noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, has antidepressant effects in patients with major depression. Potential limitations of this study are the small number of subjects and low doses of memantine. The expected sample size would be 39 per group based on a moderate difference (phi=0.30) in response rates. However, the observed effect was zero based on the response rates and favored placebo in the depression ratings. Although the present study group size of 32 has limited power to detect the significance of the expected effect, the effect size itself suggests no difference. A very large trial with similar response rates and depression levels would not show improvement on memantine. Given such an effect, the trial was ended early.

Although it is possible that higher doses of memantine may have resulted in significant antidepressant effects, the dose chosen for the present study was judged to be sufficient to test the validity of the concept of NMDA receptor antagonism with memantine. The dose of memantine used in our study was based on 1) memantine’s in vitro data of NMDA blockade, 2) NMDA’s cognitive-enhancing effects in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and 3) similar memantine plasma levels mediating both neuroprotection in animal model studies and clinical effects in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (5).

Despite these negative results, it remains possible that more potent NMDA blockade may have utility in the treatment of depression for some patients. Memantine, in contrast to ketamine, has lower affinity for the NMDA receptor, has much faster open-channel blocking/unblocking kinetics, and exhibits a different type of channel closure (i.e., “partial trapping” as opposed to “trapping block” properties) (6). Such differences might explain the lack of antidepressant properties observed with memantine in the present trial.

Received Nov. 2, 2004; revisions received March 2 and March 17, 2005; accepted April 18, 2005. From the Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program, National Institute of Mental Health, Department of Human Health Services, Bethesda, Md. Address correspondence to Dr. Zarate, 10 Center Dr., Mark O. Hatfield CRC, 7 SE, Rm. 7-3445, Bethesda, MD 20892; [email protected] (e-mail).Supported by the NIMH Intramural Research Program.Forest Laboratories supplied the study drug. None of the investigators in this study has a possible conflict of interest.

Figure 1. Mean Change in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale Total Scores From Baseline in Patients With Major Depression Who Were Treated With Memantine or Placebo for 8 Weeksa

aResponse rates at week 8 for all patients were 13% (N=2) for memantine and 13% (N=2) for placebo.

1. Zarate CA, Quiroz J, Payne J, Manji HK: Modulators of the glutamatergic system: implications for the development of improved therapeutics in mood disorders. Psychopharmacol Bull 2002; 36:35–83Medline, Google Scholar

2. Zarate CA Jr, Payne JL, Quiroz J, Sporn J, Denicoff KK, Luckenbaugh DA, Charney DS, Manji HK: An open-label trial of riluzole in patients with treatment-resistant major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:171–174Link, Google Scholar

3. Zarate CA Jr, Quiroz JA, Singh JB, Denicoff KD, De Jesus G, Luckenbaugh DA, Charney DS, Manji HK: An open-label trial of the glutamate-modulating agent riluzole in combination with lithium for the treatment of bipolar depression. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 57:430–432Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Berman RM, Cappiello A, Anand A, Oren DA, Heninger GR, Charney DS, Krystal JH: Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 47:351–354Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Parsons CG, Danysz W, Quack G: Memantine is a clinical well tolerated N–methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist—a review of preclinical data. Neuropharmacology 1999; 38:735–767Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Bolshakov KV, Gmiro VE, Tikhonov DB, Magazanik LG: Determinants of trapping block of N–methyl-D-aspartate receptor channels. J Neurochem 2003; 87:56–65Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar