A Peer-Based Assistance Program for Officers With the New York City Police Department: Report of the Effects of Sept. 11, 2001

Abstract

Few data on stress symptoms related to the World Trade Center disaster in law enforcement personnel have been reported. Most New York City Police Department (NYPD) officers had significant exposure to the events of Sept. 11, 2001. Approximately 5,000 officers responded within the first 2 days, and more than 25,000 officers worked at ground zero, the morgues, or the Staten Island landfill. Because the police are the first line of defense against terrorist attacks, it is imperative that they maintain optimal health and functioning. Concern for the long-term effects from traumatic exposure is warranted. In partnership with Project Liberty, peer officers and clinicians from the Police Organization Providing Peer Assistance performed outreach, support work, and screening for stress symptoms related to the disaster in the NYPD from December 2002 until December 2003. Psychological issues in law enforcement personnel, a description of the outreach program, and data from these screenings are presented.

Exposure to trauma is inherent in police work. It has been reported that about one-third of police officers exposed to various work-related traumatic incidents develop significant posttraumatic stress symptoms (1). Alcohol use is an acceptable, common, sometimes encouraged, legal way of relieving stress in police culture. A survey (2) found that 20% of police officers met criteria for alcohol abuse. Police work may be complicated by marital and family problems. Officers and their partners consistently find the job itself to be a source of relationship difficulties (3, 4). Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and alcohol abuse may lead to excessive aggression. Police families have been found to experience higher rates of domestic violence than the civilian population (5). All of these factors may contribute to the high rate of police suicide. The consensus is that the police suicide rate is about 1.5 times higher than the rate of suicide in the general population (6). Fears of stigmatization, negative job consequences (such as modified assignments or losing one’s weapon), and perceptions of personal weakness or failure prevent police officers from seeking assistance (7, 8). To be effective, police assistance programs must overcome these obstacles.

Method

Since 1996, the Police Organization Providing Peer Assistance (POPPA), a confidential, voluntary, independent nondepartmental assistance program for the New York City Police Department (NYPD) has used volunteer police officers as peer support officers to help fellow officers overcome resistance to seeking assistance. Volunteer peer support officers have staffed a confidential 24-hour help line where an officer can call, arrange a meeting with a peer support officer to discuss any personal problem, and receive a referral for professional assistance. To meet the needs of NYPD officers, POPPA has developed and trained a panel of more than 100 mental health professionals. All assistance from POPPA peer support officers and clinicians is confidential.

To address long-term concerns about the psychological effects of the World Trade Center disaster on NYPD officers, POPPA sent small groups of peer support officers and clinicians to roll calls at each precinct or command of the NYPD. They presented an overview of September 11th- and work-related trauma, trauma and stress symptoms, effects on the individual at work and at home, effects on the family, and how to seek assistance. Officers were given a handout listing common stress symptoms and complications (such as agitation, excessive alcohol use, work and family problems). After these 15–20-minute group presentations, peer support officers and clinicians met with officers for individual crisis counseling, to discuss individual questions or concerns, and to screen for individual reactions to the events of Sept. 11, 2001. Individual counseling sessions were informal, unstructured, and usually lasted for approximately 20 minutes. A confidential Project Liberty screening form was completed for each individual encounter listing basic demographic information, event reactions, and referrals made. POPPA personnel were instructed to report only current signs still present and attributed to the September 11th attacks—not from other incidents. To allay the officers’ fears of personal information going to the NYPD, the screening forms were completed the same day but after leaving the location of intervention. Data for the project were obtained from these forms. We obtained a waiver of the need for informed consent from the institutional review board of the State University of New York, Stony Brook.

Results

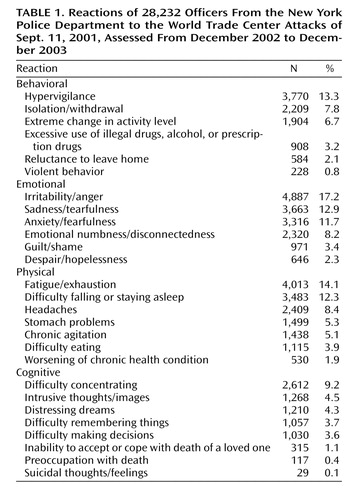

All event reactions listed on the screening form are presented in Table 1. By the end of 2003, 28,232 individual contact sheets had been completed from an estimated population of 39,000 officers. Thirty-four percent of the officers reported at least one current behavioral symptom in response to the attacks. The most common behavioral symptoms were hypervigilance or social isolation/withdrawal. Over half of the NYPD officers reported at least one current emotional symptom, such as sadness, irritability/anger, or anxiety/fearfulness. Many officers reported feelings of guilt or shame or feeling emotionally numb or disconnected. Forty-three percent reported at least one current physical symptom, such as headaches, insomnia, or fatigue. Many officers reported chronic agitation or stomach problems. Twenty-four percent reported at least one current cognitive reaction symptom in relation to the attacks. The officers complained of poor concentration and distressing dreams or intrusive thoughts/images related to the attacks. Of significance is that over 68% of the officers reported at least one disaster-related stress symptom still current 15–27 months after the World Trade Center attacks. Over 28% of the officers reported three or more stress-related symptoms that they attributed to the World Trade Center attacks. Of those interviewed, more than 5,700 officers (20%) reported such significant difficulties in response to the attacks that they were advised to seek further assistance.

Discussion

Despite stereotypes that portray police officers as heroic and invincible, these data demonstrate that NYPD officers remained significantly affected by the World Trade Center attacks 1.5–2 years after the event. Although we are cautious not to overstate the interpretation of these data, most of the rank and file of the NYPD reported that they were still suffering from stress-related symptoms from September 11th at the end of 2003. This would suggest that they are more vulnerable to PTSD and other psychological trauma-related conditions as they are exposed to future job-related traumatic incidents and/or terrorist attacks. In addition, studies have shown that significant trauma symptoms, even without meeting criteria for PTSD, may lead to social- and work-related functional impairment (9).

There are some limitations to these data. The rates of clinical diagnoses, such as PTSD, depression, or panic disorder, cannot be determined from these data because the survey information was obtained by paraprofessionals whose training and objectives were to provide education, outreach, and support—not to make diagnoses. No structured clinical interview or established scales were used. Variations in the availability of time or space may have affected some officers’ reporting of symptoms. Completion of the screening forms after leaving the intervention site may have affected the accuracy of reported information. No data from before September 11th are available for comparison, and it is possible that some officers may have reported symptoms that were related to another event. Nonetheless, it remains most noteworthy that the majority of the rank and file of the NYPD reported that they were still suffering from stress-related symptoms from September 11th by the end of 2003.

Another significant outcome of this project is the demonstration that peer officers can be effectively used to assist police officers with postdisaster-related stress. More than 28,000 of approximately 39,000 officers were reached during this project. A population that usually is reluctant to admit personal problems or stress-related symptoms was willing to discuss such issues with trained volunteer peers. These experiences will be used to develop future programs that are needed to address the long-term needs of NYPD officers. Other emergency services organizations may benefit from similar peer-based assistance programs.

|

Received Nov. 17, 2004; revision received Jan. 31, 2005; accepted April 1, 2005. From the Police Organization Providing Peer Assistance. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Dowling, Police Organization Providing Peer Assistance, 26 Broadway, Suite 1640, New York, NY 10004; [email protected] (e-mail). Project Liberty Poppa was funded by Project Liberty, the September 11th World Trade Center Disaster crisis counseling program for New York State, which was funded by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

1. Carlier IVE, Lamberts RD, Gersons BPR: Risk factors for posttraumatic stress symptomatology in police officers: a prospective analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:498–506Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Gershon R: National Institutes of Justice Final Report: “Project Shields.” Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, 2000Google Scholar

3. Kirschman E: The way it is: givens and realities of police work, in I Love a Cop: What Police Families Need to Know. New York, Guilford, 1997, pp 3-16Google Scholar

4. Finn P, Tomz JE: Developing a Law Enforcement Stress Program for Officers and Their Families. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice, 1996Google Scholar

5. Neidig PH, Russell HE, Seng AF: Interspousal aggression in law enforcement personnel attending the FOP biennial conference. National Fraternal Order of Police Journal, Fall/Winter 1992, pp 25-28Google Scholar

6. Hacket DP: Suicide and the police, in Police Suicide: Tactics for Prevention. Edited by Hackett DP, Violanti JM. Springfield, Ill, Charles C Thomas, 2003, pp 7-15Google Scholar

7. Deisinger ER: A Final Grant Report of the Law Enforcement Assistance and Development Program: Reduction of Familial and Organizational Stress in Law Enforcement. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Justice, National Criminal Justice Reference Service, 2003Google Scholar

8. Miller L: Tough guys: psychotherapeutic strategies with law enforcement and emergency services personnel. Psychotherapy 1995; 32:592–600Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Zlotnik C, Franklin LC, Zimmerman M: Does “subthreshold” posttraumatic stress disorder have any clinical significance? Compr Psychiatry 2002; 43:413–419Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar