Validity of DSM-IV Conduct Disorder in 4½–5-Year-Old Children: A Longitudinal Epidemiological Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This longitudinal study of a nonreferred, population-based sample tested the concurrent, convergent, and predictive validity of DSM-IV conduct disorder in children 4½–5 years of age. METHOD: In the Environmental Risk Longitudinal Twin Study, a representative birth cohort of 2,232 children, the children’s mothers were interviewed and the teachers completed mailed questionnaires to assess the children’s past 6-month conduct disorder symptoms. Children with three or more symptoms were diagnosed with conduct disorder, and a subset with five or more symptoms was diagnosed with “moderate-to-severe” conduct disorder. RESULTS: The prevalence of conduct disorder and moderate-to-severe conduct disorder were 6.6% and 2.5%, respectively. Children diagnosed with conduct disorder were significantly more likely than comparison subjects to self-report antisocial behaviors, to behave disruptively during observational assessment, and to have risk factors known to be associated with conduct disorder in older children (effect sizes ranging from 0.26 to 1.24). Five-year-olds diagnosed with conduct disorder were significantly more likely than comparison subjects to have behavioral and educational difficulties at age 7. Increased risk for educational difficulties at age 7 persisted after control for IQ and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder diagnosis at age 5. CONCLUSIONS: Behavioral problems of preschool-age children meeting diagnostic criteria for conduct disorder should not be ignored. Appropriate intervention should be provided to prevent ongoing behavioral and academic problems.

Childhood conduct disorder is a top mental health priority (1). Evidence from prospective longitudinal data shows that childhood conduct disorder precedes a variety of major axis I psychiatric disorders (2), suggesting that treating conduct disorder might significantly reduce the burden of adult mental disorder. Preschool intervention is desirable to prevent chronic conduct disorder (3). To intervene early, valid methods must be available to diagnose conduct disorder in young children, and in this Journal, Keenan and Wakschlag (4) called for studies of the validity of conduct disorder diagnoses in children under age 6. This article responds, reporting the validity of applying the DSM-IV conduct disorder diagnosis to a representative, nonreferred sample of over 2,000 4½–5-year-old boys and girls.

The validity of the DSM-based conduct disorder diagnosis in very young children can be ascertained by testing its concurrent, convergent, and predictive validity (5). In the present study, the diagnosis of conduct disorder would have concurrent validity if children with and without a conduct disorder diagnosis differed on other, independent measures of conduct problems. The diagnosis would have convergent validity if children with and without a conduct disorder diagnosis differed on measures of risk factors that are known to correlate with conduct disorder in older children. Risk factors associated with conduct disorder in older children include male sex, sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., low income, teen motherhood), quality of family environment (e.g., domestic violence, low social support), parenting (e.g., child harm), parental psychopathology, and co-occurring behavioral and neurocognitive child characteristics (e.g., hyperactivity, low IQ) (6). The diagnosis would have predictive validity if children with and without a conduct disorder diagnosis at age 5 years differed on measures of behavioral and educational functioning later in childhood.

Additionally, we explored whether any children who were diagnosed with conduct disorder at age 5 did not have any conduct disorder symptoms 2 years later and whether these “remitted” children had outcomes at age 7 that would warrant concern.

Method

Participants

The participants were members of the Environmental Risk Longitudinal Twin (E-Risk) Study. The E-Risk Study sampling frame was two consecutive birth cohorts (1994 and 1995) in a birth register of twins born in England and Wales (7). Of the 15,906 twin pairs born in these 2 years, 71% joined the register.

The E-Risk Study probability sample was drawn with a high-risk stratification sampling procedure. High-risk families were those in which the mother had her first birth when she was 20 years of age or younger. We used this sampling 1) to replace high-risk families who were selectively lost to the register through nonresponse and 2) to ensure sufficient base rates of problem behavior, given the low base rates expected for young children. Age at first childbearing was used as the risk-stratification variable because it was present for virtually all families in the register, it is relatively free of measurement error, and early childbearing is a known risk factor for children’s problem behaviors (8, 9). The sampling strategy resulted in a final sample in which one-third of the study mothers (younger only, N=314) constituted a 160% oversample of mothers who were at high risk based on their young age at first birth (15–20 years). The other two-thirds of study mothers (N=802) accurately represented all mothers in the general population (ages 15–48) in England and Wales in 1994–1995 (estimates derived from the General Household Survey [10]). To provide unbiased statistical estimates that can be generalized to the population of British families with children born in the 1990s, the data reported in this article were corrected with weighting to represent the proportion of young mothers in that population.

The E-Risk Study sought a sample size of 1,100 families to allow for attrition in future years of the longitudinal study while retaining statistical power. An initial list of families who had same-sex twins was drawn from the register to target for home visits, with a 10% oversample to allow for nonparticipation. Of the families from the initial list, 1,116 (93%) participated in home-visit assessments when the twins were age 5 years, forming the base sample for the study: 4% of the families refused, and 3% could not be reached after many attempts. Written informed consent was obtained from the mothers. With the parents’ permission, questionnaires were mailed to the children’s teachers, and the teachers returned questionnaires for 94% of the cohort children.

A follow-up home visit was conducted 18–24 months after the children’s assessment at age 5 (hereafter called the age-7 follow-up). Follow-up data were collected for 98% of the 1,116 E-Risk Study families. At this follow-up, teacher questionnaires were obtained for 91% of the 2,232 E-Risk Study children (93% of those taking part in the follow-up). The E-Risk Study has received ethical approval from the ethics committee of Maudsley Hospital.

Conduct Disorder Diagnosis at Age 5

We derived a research diagnosis of the children’s conduct disorder based on the mothers’ and the teachers’ reports on 14 of 15 DSM-IV symptoms of conduct disorder. The symptoms covered fighting, bullying, lying, stealing, cruelty to people or animals, vandalism, and rule violations. The “forced sexual activity” symptom was excluded as inappropriate for 5-year-olds. The mothers’ reports were obtained in a face-to-face standardized interview in the family home, and the teachers’ reports were obtained through mail. A child was considered to have a given symptom if either the mother or the teacher reported the symptom as being “very true or often true” of the child over the past 6 months at 4½–5 years of age. We counted a symptom as present if reported by either source from evidence that this approach enhances diagnostic validity (11, 12). Symptom counts ranged from 0 to 11. Consistent with DSM-IV criteria, children with 3 or more symptoms were assigned a conduct disorder diagnosis. A subset of children with 5 or more symptoms was assigned a “moderate-to-severe” conduct disorder diagnosis.

Validity Measures

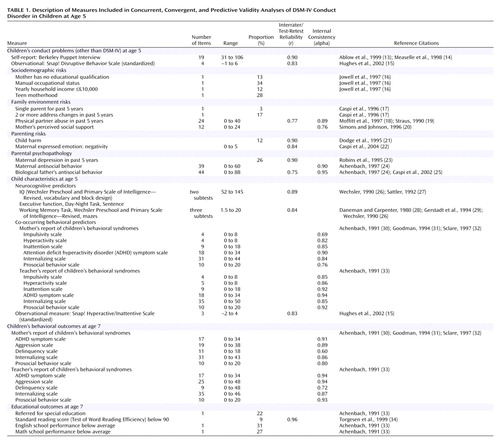

Distributions and prevalence rates in this cohort for measures used in concurrent, convergent, and predictive validity analyses (Table 1) have been reported elsewhere (9). (An appendix with detailed descriptions is available on request from the first author.)

Statistical Analysis

To provide unbiased statistical estimates that could be generalized to the population of British families with children born in the 1990s, the data reported in this article were corrected with weighting to represent the proportion of young mothers in that population (35).

Group differences were evaluated with odd ratios (for dichotomous variables) and t tests (for continuous variables). We calculated the effect sizes of the obtained group differences from the following formula:

For dichotomous variables, we estimated the standardized mean difference statistic (d) by taking the product of the log odds ratio and (square root)3/π (36). Operationally defined, d=0.2 is a small effect size, d=0.5 is a medium effect size, and d=0.8 is a large effect size (37).

Statistical analysis was complicated by the fact that our twin study contained two children from each family. Thus, we analyzed data with tests based on the sandwich or Huber/White variance estimator (38, 39) with Stata 7.0 (40), which adjusts estimated standard errors to account for the dependence in the data because of analyzing two children from the same family.

Results

Prevalence and Sex Differences

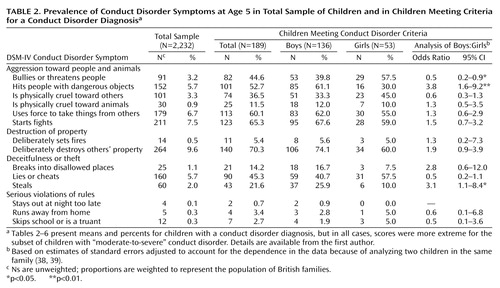

The prevalence of conduct disorder, weighted to represent the population (reported Ns are unweighted), was 6.6% (N=189) in the total sample, 9.9% (N=136) for the boys, and 3.5% (N=53) for the girls. The prevalence of “moderate-to-severe” conduct disorder, weighted to represent the population, was 2.5% (N=75) in the total sample, 4.2% (N=62) for the boys, and 0.9% (N=13) for the girls. The boys’ risk of a conduct disorder diagnosis at age 5 years was 3–5 times that of the girls (odds ratio=3.0, 95% confidence interval [CI]=2.0–4.5 for conduct disorder; odds ratio=4.9, 95% CI=2.4–9.9 for moderate-to-severe conduct disorder).

Three findings are notable about children diagnosed with conduct disorder at age 5 (Table 2). First, symptoms of aggression, theft, and destructive behavior were common, whereas rule violations were rare. Second, there were few significant sex differences in the prevalence of conduct disorder symptoms. Third, where tendencies toward sex differences were observed, conduct-disordered girls’ patterns of symptoms reflected relational aggression (e.g., bullying or threatening people, cruelty, lying, or cheating), whereas conduct-disordered boys’ pattern of symptoms reflected conventional conduct disorder symptoms (e.g., hitting others, starting fights, destroying property, stealing, and breaking into disallowed places).

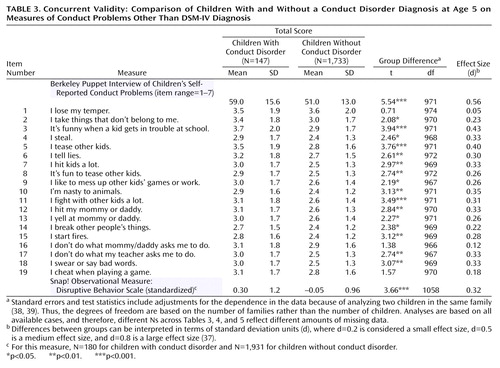

Concurrent Validity

Table 3 shows the conduct disorder group was significantly more likely than the comparison group to self-report antisocial behaviors in the Berkeley Puppet Interview (13, 14), including hitting, lying, swearing, fighting, stealing, and breaking things. Observational measurements revealed that the conduct disorder group was also significantly more disruptive than the comparison group during a competitive game of Snap! (15).

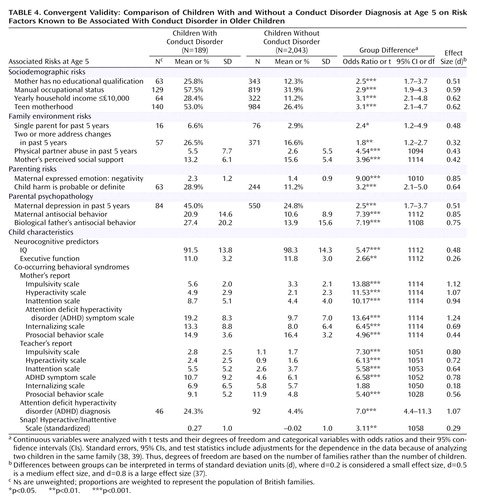

Convergent Validity

Table 4 presents risk factors known to correlate with conduct disorder in older children. Risk factors in every domain (e.g., sociodemographic, family environment, parenting, parental psychopathology, and child characteristics) differed significantly between the conduct disorder and the comparison groups. All measures of children’s co-occurring behavioral problems, based on the mothers’ and the teachers’ reports, discriminated between children with and without an age-5 conduct disorder diagnosis, except teacher-reported internalizing behavior. The largest effect sizes were observed for the children’s behaviors related to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Our observational measure agreed that the conduct disorder group was rated significantly more hyperactive or inattentive than the comparison group during the Snap! game. The risk factors related to parenting and parental psychopathology were also among the strongest group discriminators (with effect sizes ranging from 0.51 to 0.85).

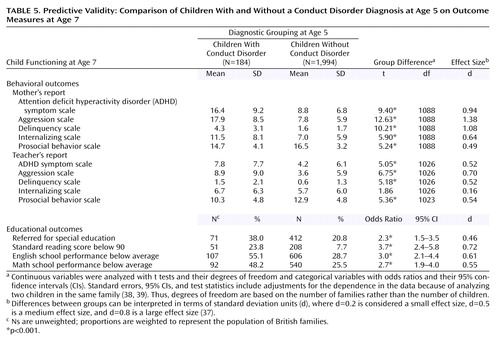

Predictive Validity

The children meeting the criteria for a conduct disorder diagnosis at age 5 years were significantly more likely than the comparison subjects to have higher levels of age-7 mother- and teacher-reported ADHD symptoms, aggression, and delinquency and lower levels of prosocial behavior (Table 5). Relative to comparison subjects, the conduct disorder group was 2–4 times more likely to have age-7 educational problems. After we controlled for age-5 IQ and ADHD diagnosis, the conduct disorder group continued to be at an increased risk for poorer reading (adjusted odds ratio=2.0, 95% CI=1.2–3.2), English (adjusted odds ratio=1.8, 95% CI=1.2–2.8), and math (adjusted odds ratio=1.6, 95% CI=1.0–2.4) skills. Sixty-five percent of the children with a conduct disorder diagnosis and 80% of the children with a moderate-to-severe conduct disorder diagnosis at age 5 years had one or more educational problems at age 7 years.

Continuity or Change?

Compared to undiagnosed children, the age-5 conduct disorder group was at a significantly greater risk for a conduct disorder diagnosis at age 7 years (odds ratio=20.6, 95% CI=12.5–34.1). More boys than girls maintained a conduct disorder diagnosis at both ages (odds ratio=3.8, 95% CI=1.1–12.6).

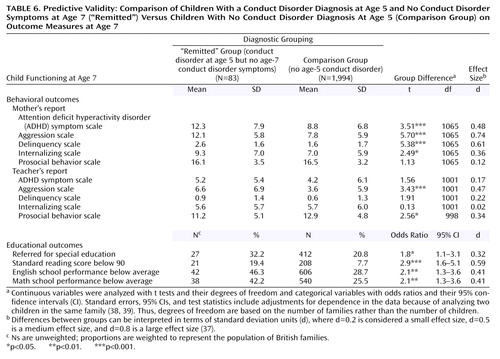

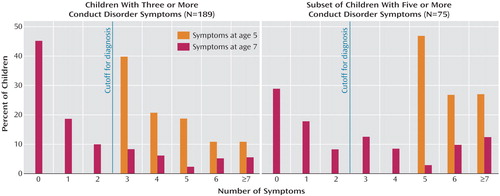

Despite this continuity, among the 189 5-year-olds who met the diagnostic criteria for conduct disorder, 83 (49% weighted) had no conduct disorder symptoms at age 7 (Figure 1). However, of the subset of 75 children who met the diagnostic criteria for moderate-to-severe conduct disorder at 5 years of age, only 21 (28% weighted) had no conduct disorder symptoms at age 7 years. We compared the group of children who had an age-5 conduct disorder diagnosis and no age-7 conduct disorder symptoms (“remitted” group) against the children who did not have an age-5 conduct disorder diagnosis (comparison group) on age-7 outcome measures (Table 6). The findings suggested that the “remitted” children continued to experience clinically significant behavioral and academic difficulties 2 years later, despite their apparent remission from conduct disorder.

Discussion

The utility of a diagnostic framework lies primarily in its ability to identify individuals who may need treatment. Applying DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for conduct disorder to 4½–5-year-old children appears to have succeeded in doing that. In a nonreferred, population-based sample, the conduct disorder diagnosis classified a small subset of children who were aggressive and antisocial. They also had lower executive functioning, lower IQ, and co-occurring ADHD symptoms—neurodevelopmental hallmarks of life-course persistent antisocial behavior (41). Moreover, diagnosed children were disproportionately likely to come from backgrounds marked by low social class, single parenthood, family disruption, and parental psychopathology. Conduct-disordered children in our sample were disproportionately likely to have experienced harsh parenting and physical harm. Thus, the life contexts of young children identified as having conduct disorder in our study resemble the “criminogenic” environments that have been shown to interact with neurodevelopmental vulnerabilities to exacerbate behavior problems and promote antisocial personality development (41). Concerns about the welfare of children diagnosed with conduct disorder increase, given that these children, regardless of whether they had any conduct disorder symptoms at follow-up, were disproportionately likely to have continuing behavioral and educational difficulties. Effect sizes for the association between risk factors and conduct disorder in our sample of young children are comparable to those reported for older children (42, 43).

Whether valid diagnoses can be made of disruptive behavior disorders in preschool-age children has been a focus of controversy (4, 44, 45). Some argue that disruptive behaviors in young children should not be pathologized because aggressive, destructive, and defiant behaviors, which characterize conduct disorder, are thought to be common and developmentally normative in the preschool period (46), and most children will outgrow them (47). Others believe that children falsely identified as having conduct disorder may be stigmatized, and unnecessary referral for treatment may waste health care resources. Some argue that the predictive accuracy of conduct problems for future conduct disorder improves only when children are older (48), and applying diagnostic criteria validated for older children and adolescents to young children (i.e., “down-aging”) may promote overdiagnosis (44).

Our research demonstrated that the co-occurrence of three or more conduct disorder symptoms, constituting a syndrome of problems, is rare and signals poor outcome. In this study, a large majority of children who had at least three (65%) or at least five (80%) DSM-IV conduct disorder symptoms at age 5 years, regardless of age-7 conduct disorder symptom status, had at least one educational difficulty 2 years later. Furthermore, the fact that the children’s conduct disorder diagnosis continued to predict teacher-rated educational difficulties at follow-up, after we controlled for age-5 IQ and ADHD diagnosis, suggests that the conduct disorder diagnosis uniquely captures a subset of young children who may have enduring school-related problems and on whom treatment resources would not have been wasted.

Clinicians wishing to minimize the risk of treating “false positives” can adopt a conservative approach by applying more stringent diagnostic criteria for moderate-to-severe conduct disorder. Moreover, diagnostic precision might be improved if specific age-appropriate guidelines are developed (47). However, the present study shows that minimum DSM-IV criteria for a conduct disorder diagnosis were sensitive enough to identify young children who might benefit from intervention. Long-term studies of early-onset antisocial behavior have shown that true recoveries from conduct disorder are extremely rare because although not all conduct disorder children grow up to have antisocial personality disorder, virtually all children with conduct disorder have mental disorders and poor functioning in adulthood (41). Fortunately, evidence has shown that interventions for preventing chronic conduct disorder can be effective if applied early in life (49).

Four limitations temper the findings of this study. First, our sample comprised mostly white twins living in England and Wales. Therefore, our findings may not generalize to other ethnic or racial groups in other countries or to singletons. However, our estimate of the prevalence of conduct disorder of 2.5%–6.6% and the sex ratio of 3–5 boys per girl are comparable to other epidemiological studies of singletons in the United States (50–52). Second, we could not address the validity of the oppositional defiant disorder diagnosis because it was not assessed. Third, we report findings based on a “research” diagnosis that may differ from typical practice in clinical settings. However, we interviewed mothers face-to-face to assess symptoms and did not rely on self-administered checklists. Fourth, predictive validity analyses were limited to a 2-year follow-up period. Predictive validity for later childhood and adolescence should be tested.

The strengths of this study include features that directly address the limitations of existing research identified by Keenan and Wakschlag (4): i.e., equal representation of preschool-age girls and boys in a large population-based sample, both teacher and mother reports of DSM-IV conduct disorder symptoms, and a longitudinal design with a high retention rate (98%).

Recently, a standardized interview (53) and observational (54) methods for making diagnoses in preschool-age children have been developed. This study adds to those efforts by demonstrating that interviewing mothers and gathering collateral reports from teachers can validly identify young children with DSM-IV conduct disorder.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Received July 28, 2003; revision received Jan. 30, 2004; accepted May 10, 2004. From the Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College, London; and the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Kim-Cohen, Social, Genetic, and Developmental Psychiatry Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, P.O. Box 80, De Crespigny Park, London SE5 8AF, U.K.; [email protected] or [email protected] (e-mail). Dr. Kim-Cohen was supported by a grant from the NIMH Training Program in Emotion Research (T32-MH-18931), and Dr. Moffitt is a recipient of a Royal Society-Wolfson Research Merit Award. The Environmental Risk Longitudinal Twin Study is funded by the United Kingdom Medical Research Council (G9806489). The authors thank the study families and teachers for their participation, Robert Plomin and Michael Rutter for their contributions, Hallmark Cards for its support, Thomas Achenbach for his permission to adapt the Child Behavior Checklist, and members of the Environmental Risk Longitudinal Twin Study team for their dedication and hard work.

Figure 1. The Distribution of Conduct Disorder Symptoms Among Children Meeting Diagnostic Criteria for Conduct Disorder at Age 5

1. Priorities for Prevention Research at NIMH: A Report by the National Advisory Mental Health Council Workgroup on Mental Disorders Prevention Research: NIH Publication 98–4321. Bethesda, Md, National Institutes of Health, 1998Google Scholar

2. Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington HL, Milne B, Poulton R: Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:709–717Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Bennett KJ, Offord DR: Conduct disorder: can it be prevented? Curr Opin Psychiatry 2001; 14:333–337Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Keenan K, Wakschlag LS: Can a valid diagnosis of disruptive behavior disorder be made in preschool children? Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:351–358Link, Google Scholar

5. Anastasi A: Psychological Testing, 7th ed. New York, Macmillan, 1996Google Scholar

6. Lahey BB, Moffitt TE, Caspi A: Causes of Conduct Disorder and Juvenile Delinquency. New York, Guilford, 2003Google Scholar

7. Trouton A, Spinath FM, Plomin R: Twins Early Development Study (TEDS): a multivariate, longitudinal genetic investigation of language, cognition, and behavior problems in childhood. Twin Res 2002; 5:444–448Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Maynard RA: Kids Having Kids: Economic Costs and Social Consequences of Teen Pregnancy. Washington, DC, Urban Institute Press, 1997Google Scholar

9. Moffitt TE, E-Risk Study Team: Teen-aged mothers in contemporary Britain. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2002; 43:727–742Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Bennett N, Jarvis L, Rowlands O, Singleton N, Haselden L: Living in Britain: results from the General Household Survey. London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1996Google Scholar

11. Bird HR, Gould MS, Staghezza B: Aggregating data from multiple informants in child psychiatry epidemiological research. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:78–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Piacentini JC, Cohen P, Cohen J: Combining discrepant diagnostic information from multiple sources: are complex algorithms better than simple ones? J Abnorm Child Psychol 1992; 20:51–63Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Ablow JC, Measelle JR, Kraemer HC, Harrington R, Luby J, Smider N, Dierker L, Clark V, Dubicka B, Heffelfinger A, Essex MJ, Kupfer DJ: The MacArthur Three-City Outcome Study: evaluating multi-informant measures of young children’s symptomatology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:1580–1590Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Measelle JR, Ablow JC, Cowan PA, Cowan CP: Assessing young children’s views of their academic, social, and emotional lives: an evaluation of the self-perception scales of the Berkeley Puppet Interview. Child Dev 1998; 69:1556–1576Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Hughes C, Oksanen H, Taylor A, Jackson J, Murray L, Caspi A, Moffitt TE: “I’m gonna beat you!” SNAP! an observational paradigm for assessing young children’s disruptive behavior in competitive play. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2002; 43:507–516Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Jowell R, Cutice J, Park A, Brook L, Thomson K, Bryson C: British Social Attitudes: The 14th Report. Aldershot, England, Ashgate, 1997Google Scholar

17. Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Thornton A, Freedman D, Amell JW, Harrington H, Smeijers J, Silva PA: The Life History Calendar: a research and clinical assessment method for collecting retrospective event-history data. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 1996; 6:101–114Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Krueger RF, Magdol L, Margolin G, Silva PA, Sydney R: Do partners agree about abuse in their relationship? a psychometric evaluation of interpartner agreement. Psychol Assess 1997; 9:47–56Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Straus MA: Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: the Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales, in Physical Violence in American Families: Risk Factors and Adaptations to Violence in 8,145 Families. Edited by Straus MA, Gelles RJ. New Brunswick, NJ, Transaction, 1990, pp 403–424Google Scholar

20. Simons RL, Johnson C: The impact of marital and social network support on quality of parenting, in Handbook of Social Support and the Family. Edited by Pierce GR, Sarason BR, Sarason IG. New York, Plenum, 1996, pp 269–287Google Scholar

21. Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Valente E: Social information-processing patterns partially mediate the effect of early physical abuse on later conduct problems. J Abnorm Psychol 1995; 104:632–643Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Morgan J, Rutter M, Taylor A, Arseneault L, Tully L, Jacobs C, Kim-Cohen J, Polo-Tomas M: Maternal expressed emotion predicts children’s antisocial behavior problems: using monozygotic-twin differences to identify environmental effects on behavioral development. Dev Psychol 2004; 40:149–161Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Robins LN, Cottler L, Bucholtz K, Compton W: National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. St Louis, Washington University School of Medicine, 1995Google Scholar

24. Achenbach TM: Manual for the Young Adult Self-Report and Young Adult Behavior Checklist. Burlington, University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, 1997Google Scholar

25. Caspi A, Taylor A, Smart M, Jackson J, Tagami S, Moffitt TE: Can women provide reliable information about their children’s fathers? cross-informant agreement about men’s lifetime antisocial behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2002; 42:915–920Crossref, Google Scholar

26. Wechsler D: Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence—Revised. London, Psychological Corp (Harcourt, Brace), 1990Google Scholar

27. Sattler JM: Assessment of Children: WISC-III and WPPSI-R Supplement. San Diego, Jerome M Sattler, 1992Google Scholar

28. Daneman M, Carpenter PA: Individual differences in working memory and reading. J Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior 1980; 19:450–466Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Gerstadt CL, Hong YJ, Diamond A: The relationship between cognition and action: performance of children 3.5–7 years old on a Stroop-like day-night test. Cognition 1994; 53:129–153Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Achenbach TM: Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, 1991Google Scholar

31. Goodman R: A modified version of the Rutter Parent Questionnaire including extra items on children’s strengths: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1994; 35:1483–1494Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Sclare I: The Child Psychology Portfolio. Windsor, Berkshire, UK, National Foundation for Educational Research-Nelson, 1997Google Scholar

33. Achenbach TM: Manual for the Teacher’s Report Form and 1991 Profile. Burlington, University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, 1991Google Scholar

34. Torgesen JK, Wagner RK, Rashotte CA: Test of Word Reading Efficiency. Austin, Tex, PRO-ED, 1999Google Scholar

35. Birth Statistics: Series FM1, Number 23. London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1996Google Scholar

36. Haddock CK, Rinkdskopf D, Shadish WR: Using odds ratios as effect sizes for meta-analysis of dichotomous data: a primer on methods and issues. Psychol Methods 1998; 3:339–353Crossref, Google Scholar

37. Cohen J: A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992; 112:155–159Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Rogers WH: Regression standard errors in clustered samples. Stata Technical Bull 1993; 13:19–23Google Scholar

39. Williams RL: A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometrics 2000; 56:645–646Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Stata Statistical Software, Release 7.0. College Station, Tex, Stata Corp, 2003Google Scholar

41. Moffitt TE: Life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial behavior: a 10-year research review and research agenda, in Causes of Conduct Disorder and Juvenile Delinquency. Edited by Lahey BB, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. New York, Guilford, 2003, pp 49–75Google Scholar

42. Nigg JT, Huang-Pollock CL: An early-onset model of the role of executive functions and intelligence in conduct disorder/delinquency, in Causes of Conduct Disorder and Juvenile Delinquency. Edited by Lahey BB, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. New York, Guilford, 2003, pp 227–247Google Scholar

43. Rowe R, Maughan B, Pickles A, Costello EJ, Angold A: The relationship between DSM-IV oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: findings from the Great Smoky Mountains Study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2002; 43:365–373Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. McClellan JM, Speltz ML: Psychiatric diagnosis in preschool children (letter). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:127–128Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Spencer TJ, Monuteaux M: Psychiatric diagnosis in preschool children: Dr Wilens et al reply (letter). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:128–129Crossref, Google Scholar

46. Tremblay RE, Japel C: Prevention during pregnancy, infancy and the preschool years, in Early Prevention of Adult Antisocial Behaviour. Edited by Farrington DP, Coid JW. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 2003, pp 205–242Google Scholar

47. Campbell SB: Behavior Problems in Preschool Children: Clinical and Developmental Issues, 2nd ed. New York, Guilford, 2002Google Scholar

48. Bennett KJ, Offord DR: Screening for conduct problems: does the predictive accuracy of conduct disorder symptoms improve with age? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:1418–1425Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Olds DL, Henderson CR, Cole R, Eckenrode J, Kitzman H, Luckey D, Pettitt L, Sidora K, Morris P, Powers J: Long-term effects of nurse home visitation on children’s criminal and antisocial behavior: 15-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998; 280:1238–1244Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Cohen P, Cohen J, Kasen S, Velez CN, Hartmark C, Johnson J, Rojas M, Brook J, Streuning EL: An epidemiological study of disorders in late childhood and adolescence, I: age- and gender-specific prevalence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1993; 34:851–867Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A: Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:837–844Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Lahey BB, Loeber R, Quay HC, Applegate B, Shaffer D, Waldman I, Hart EL, McBurnett K, Frick PJ, Jensen P, Dulcan M, Canino G, Bird H: Validity of DSM-IV subtypes of conduct disorder based on age of onset. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37:435–442Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Egger HL, Angold A: The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA): a structured parent interview for diagnosing psychiatric disorders in preschool children, in Handbook of Infant and Toddler Mental Health Assessment. Edited by DelCarmen-Wiggins R, Carter AS. New York, Oxford University Press, 2004, pp 223–243Google Scholar

54. Wakschlag L, Danis B: Assessment of disruptive behavior in young children: a clinical-developmental framework, in Handbook of Infant and Toddler Mental Health Assessment. Edited by DelCarmen-Wiggins R, Carter AS. New York, Oxford University Press, 2004, pp 421–440Google Scholar