Male Body Image in Taiwan Versus the West: Yanggang Zhiqi Meets the Adonis Complex

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Body image disorders appear to be more prevalent in Western than non-Western men. Previous studies by the authors have shown that young Western men display unrealistic body ideals and that Western advertising seems to place an increasing value on the male body. The authors hypothesized that Taiwanese men would exhibit less dissatisfaction with their bodies than Western men and that Taiwanese advertising would place less value on the male body than Western media. METHOD: The authors administered a computerized test of body image to 55 heterosexual men in Taiwan and compared the results to those previously obtained in an identical study in the United States and Europe. Second, they counted the number of undressed male and female models in American versus Taiwanese women’s magazine advertisements. RESULTS: In the body image study, the Taiwanese men exhibited significantly less body dissatisfaction than their Western counterparts. In the magazine study, American magazine advertisements portrayed undressed Western men frequently, but Taiwanese magazines portrayed undressed Asian men rarely. CONCLUSIONS: Taiwan appears less preoccupied with male body image than Western societies. This difference may reflect 1) Western traditions emphasizing muscularity and fitness as a measure of masculinity, 2) increasing exposure of Western men to muscular male bodies in media images, and 3) greater decline in traditional male roles in the West, leading to greater emphasis on the body as a measure of masculinity. These factors may explain why body dysmorphic disorder and anabolic steroid abuse are more serious problems in the West than in Taiwan.

Over the last several decades, disorders of body image have grown increasingly common among men in Western societies (1). Body dysmorphic disorder, once considered uncommon (2), is now recognized as a common disorder afflicting 1% to 2% of Western men (3–5). One form of this disorder, “muscle dysmorphia,” characterized by a pathological preoccupation with muscularity (6, 7), appears to be growing in prevalence and severity among Western men (1, 7–9). These pathological body image concerns, sometimes popularly called the “Adonis complex,” have attracted much attention in Western media (10–13). By contrast, male body image disorders appear to be rare in non-Western societies; for example, we are aware of only a single case report of muscle dysmorphia in Asia (14).

Another serious consequence of male body image concerns is abuse of anabolic-androgenic steroids and other “body image drugs” (15–17). Anabolic steroids are widely abused in the United States, Europe, and Australia and represent a major public health problem (1, 18–21). By contrast, in our experience, anabolic steroid abuse appears to be extremely rare in non-Western societies (aside from occasional elite athletes); for example, we are not aware of any published studies of anabolic steroid abuse in Asian countries.

Why do Western men seem so vulnerable to body image problems? Recent studies suggest two possible explanations: 1) Western men may harbor unrealistic body ideals, and 2) Western society is placing an increasing “value” on the male body.

We examined the first of these two phenomena: it has long been recognized that Western women may have body image problems (22–25), but only recently have studies focused on men (1, 26). We have recently attempted to augment this research by creating a computerized measure of body image perception, the “somatomorphic matrix” (27). This instrument, described in detail previously (27, 28), presents the subject with an image of a male body that he can adjust on the computer screen through 10 levels of muscularity and 10 levels of fat (i.e., a total of 100 possible images). The subject is then asked to choose the images best representing 1) his own body, 2) the body of an average man of his age in his country, 3) the body that he ideally would like to have, and 4) the body that he thinks that women would prefer the most. When we administered the somatomorphic matrix to college-age men in the United States, France, and Austria, subjects in all three countries picked an ideal body image that was about 28 lb (13 kg) more muscular than themselves, and they estimated that women preferred a male body about 30 lb (14 kg) more muscular than themselves (28). Of interest, however, when we presented the images to actual women, they preferred a male body much closer to that of an average man, with little added muscle (27, 28).

Lynch and Zellner (29), using male figure drawings showing different levels of muscularity, obtained results that were similar to ours: American college men chose an ideal body image far more muscular than themselves and also estimated that women prefer a very muscular male body. However, actual college women, as in our study, did not prefer a male figure drawing with large muscles. Of interest, when Lynch and Zellner administered their figure drawings to middle-aged men, the findings changed: there were few differences between these men’s estimates of their own muscularity, their ideal muscularity, and the muscularity that they think women prefer.

We then turned to the second phenomenon we listed: Western society may be amplifying men’s body image concerns by placing increasing value and attention on the male body as a measure of masculinity (1). Although this trend is difficult to quantify, the rising value of the male body can be gauged to some degree by examining male models in advertisements in women’s magazines. In a recent study (30), we counted the numbers of male and female models appearing in advertisements in two leading American women’s magazines and calculated the proportion of these models portrayed in a state of undress (defined as showing more bare body than would be normally acceptable on a city street). From 1958 to 1998, the proportion of undressed female models remained relatively stable, at about 20%, whereas the proportion of undressed male models rose from as little as 3% in the 1950s to as much as 35% in the 1990s. This trend may indicate a rising relative value for the male body—at least as gauged by the behavior of advertisers selling products to women.

Are these two phenomena peculiar to Western societies? To test this question, we attempted to replicate these two studies—the “somatomorphic matrix” study (28) and the women’s magazine study (30)—in Taiwan. Given the lower prevalence of body image disorders and anabolic steroid use among Taiwanese men, we hypothesized 1) that these men would display much less discrepancy between body reality and body ideal than their Western counterparts and 2) that Taiwanese magazine advertisements would place much less value on the male body than Western magazine advertisements.

Study I: Body Image in Taiwanese Men

Method

For study I, we recruited male undergraduate students at a university in Tainan, Taiwan, for a “study examining body image perception” in which they would have their height, weight, and body fat measured, followed by a brief computerized test. For participation in the study, which required approximately 10–15 minutes, the students were given 150 Taiwanese dollars (about $5 U.S.). All subjects signed informed consent for the study after the full study procedures had been explained, which was approved by McLean Hospital’s institutional review board.

We first measured each subject’s height, weight, and body fat; we also calculated an index of his muscularity, the fat-free mass index, using methods described previously (28). However, since these measurements used equations developed for Caucasian men (31, 32)—and thus possibly inaccurate for Asian subjects—we did not use them for our primary analysis, as we explain. We next asked each subject to perform the somatomorphic matrix test described earlier. Although all subjects were at least proficient in English, we translated the test instructions into Chinese and placed them next to the computer for the subject’s reference to eliminate any possible confusion from the English instructions. In the test, the subject was asked to choose images representing his best estimate of 1) his own body (“perceived man”), 2) the body average of an average Taiwanese man of his age (“average man”), 3) the body that he would ideally like to have (“ideal man”), and 4) the male body that he thought women would like best (“women’s preferred man”). The computer then recorded the percent body fat and the degree of muscularity (the latter expressed in units of fat-free mass index, ranging from 16 to 30 kg/m2 [see reference 32]) for each of the four images chosen.

We then compared group means on each of the four images using a random effects linear regression model, as described previously (28). Standard errors were calculated by using generalized estimating equations, with compound symmetry as a working covariance structure, to account for the correlation of observations within individuals (33). We did not include the subjects’ own measured fat and muscularity in these comparisons because actual body measurements were based on equations derived from Caucasian subjects and were hence unreliable, as noted.

Results

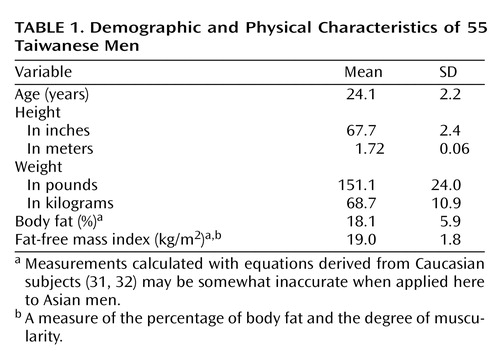

We recruited 55 young men, all Taiwanese and of Chinese origin (i.e., all descendants of post-1600s Chinese migrations to Taiwan, rather than descendants of the pre-1600s Malay-Polynesian migrations). Demographic features of the subjects are summarized in Table 1; all subjects identified themselves as heterosexual—an issue of methodological importance since homosexual orientation may itself substantially influence body image perception (34–36). On the body fat indices (Table 2), we found no significant differences between the men’s mean perceived body fat and the mean levels of body fat that they chose on the three other computer questions; in other words, the 95% confidence intervals for all comparisons included 0 (Table 2). Indeed, all means were within only 2.1% of the mean perceived body fat, and a difference of 2.1% of body fat is virtually imperceptible to the naked eye (1, 32).

On the muscularity (fat-free mass index) indices, however, prominent differences emerged (Table 3): the men chose an ideal body image about 2.0 kg/m2 more muscular than what they perceived themselves to be—a significant difference (p<0.001). They also showed a modest, although significant, difference between their perceived muscularity and the muscularity that they estimated was preferred by women (1.2 kg/m2) (p=0.005).

When we compared these results with those of men from the United States and Europe in our previous study (28), it seems that men in both the East and the West would ideally like to be more muscular. But when they were asked to estimate the male body that women prefer (probably a more practical and more objectively verifiable index than an abstract body “ideal”), the Taiwanese men appeared much more comfortable with their body appearance than their Western counterparts. Specifically, among the 200 European and American men in our previous study (28), the mean discrepancy between the men’s perceived muscularity and their estimate of women’s preferred muscularity was 2.35 kg/m2 (SD=2.5), whereas among the 55 Taiwanese men, the discrepancy was only half as great at 1.20 kg/m2 (SD=3.2)—a significant difference (t=2.82, df=253, p=0.005).

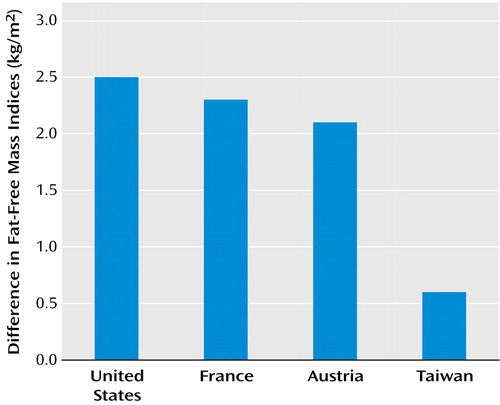

The contrast between East and West was even clearer when we examined the difference between the men’s estimate of the muscularity of an “average man” in their culture and their estimate of “women’s preferred man” for muscularity. In the three Western countries, this difference ranged from 2.11 kg/m2 (Austria) to 2.46 kg/m2 (United States), but it was only 0.6 kg/m2 in Taiwan (Figure 1). When we translated these findings into conventional terms, we found that American men think that American women prefer a male body with about 20 lb more muscle than an average American man, whereas Taiwanese men estimate only a 5-lb difference on the same comparison.

Study II: Male Body Image in Taiwanese and American Magazine Advertising

Method

We next sought to compare the value of the male body in American versus Taiwanese magazine advertising using our method of counting dressed and undressed advertising models in women’s magazines as described here and in a previous article (30). For the United States, we chose the two leading women’s magazines examined in our earlier study, Cosmopolitan and Glamour. For Taiwan, the most closely comparable magazines were Bella,Vivi, and the Taiwanese version of Cosmopolitan. As in our previous study, we counted the number of male and female images in advertisements in each magazine and the percentage of men and women in these images who were portrayed as undressed. In general, “undressed” was defined, as in our previous article, as insufficiently dressed to be seen on a city street. However, we slightly expanded this definition for the present study to include men with prominent exposure of the biceps, pectoral, or abdominal muscles. For the Taiwanese magazines, we further divided the images into Western and Asian models. For each of the five magazines, we totaled the images from all issues in 2001. Comparisons between the proportions of undressed models in different categories were computed by Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed. Further details of the rating criteria and the methods of assessing interrater reliability have been published previously (30).

Results

In the Taiwanese magazines from 2001, we found more than 1,000 advertisements that used male or female models (Table 4), advertising a wide variety of products—some body-related (i.e., clothes, perfume) and others not (i.e., food, tobacco)—from both Western and Asian manufacturers. When we compared the Taiwanese advertisements with our earlier American data, we found only modest differences in the prevalence of undressed male and female Western models in either the United States or Taiwan, with the Taiwanese magazines actually showing more nudity in both sexes than their American counterparts. Asian women, however, were portrayed undressed only about half as often as Western women in the Taiwanese magazines, and most striking, Asian men were almost never shown undressed. Of 78 Asian men portrayed in the Taiwanese magazine advertisements, only four (5%) were shown undressed compared to 43% of Western men and 42% of Western women in the same magazines.

Discussion

Body image disorders and anabolic steroid use appear to be much less prevalent among Asian men than among men in the United States or other Western societies. Based on this observation, we hypothesized that Chinese men in Taiwan would display less body dissatisfaction than Western men and that Taiwanese media advertising would place less “value” on the male body than Western media advertising. These two studies offer tentative support for these predictions. In study I, Taiwanese men estimated only a 5-lb difference between the muscularity of an average man and the male body that women prefer. By contrast, European and American men estimated this same difference to be about 20 lb. In study II, Taiwanese magazine advertisements portrayed nearly half of Western men and women in a state of undress, but Asian men were shown undressed in only 5% of cases. This observation suggests that, at least in the judgment of advertisers, body appearance (at least in terms of muscularity) is not a prime criterion for defining a Chinese man as masculine, admirable, or desirable, whereas the body has greater importance in defining an American man in these ways.

These studies are subject to various limitations. In particular, study I used a computerized test designed using Caucasian models. This technique might have introduced error when the instrument was administered to Asian subjects. We attempted to minimize this limitation, however, by focusing only on comparisons among the images chosen by the subjects on the computer rather than using the actual body measurements of the subjects themselves. Since any error introduced by the Caucasian images would likely apply similarly across all images, we believe that this error did not seriously bias our comparisons among images chosen by the subjects.

A limitation of study II is that advertisements in women’s magazines provide only an approximate measure of the value of bodily appearance relative to other features that define masculinity or desirability among men. We chose to use advertisements in women’s magazines as opposed to advertisements in men’s magazines, general magazines, or other advertising media, primarily because we had already published comparable data from American women’s magazines (30) and could readily use these data for comparison with Taiwan. In short, we were using women’s magazine advertisements simply as a device to compare the cultural “value” of the male body in Taiwan versus the United States and not as an index of what men themselves prefer. Of course, the judgments of companies advertising Western and Asian products may not parallel the opinions of society as a whole, but advertisements are measured by their financial success and presumably optimized for a Taiwanese readership. Thus, it would seem unlikely that advertisers would stray very far from societal values and still remain in business. In light of these considerations and given the difficulty of designing and validating a definitive direct assessment of the value of the male body, advertising data may offer a suitable proxy.

Given these limitations, our studies must be regarded as preliminary. Nevertheless, the two studies combine to suggest that American culture, and perhaps other Western cultures, have become much more focused on male body appearance than Chinese culture (we use the term “Chinese culture” here because 98% of the Taiwanese population is descended from China, and the traditional cultural values of this majority derive almost exclusively from Chinese traditions [37]). What accounts for this difference? We propose three hypotheses: 1) Chinese culture places less emphasis on muscularity as a measure of masculinity, 2) Chinese men are less exposed to the muscular images common in American media, and 3) Chinese men have experienced less decline in their traditional male roles as “head of the household” than men in the United States and other Western countries.

We examine the first of these hypotheses: Western societies since antiquity have seen fitness and muscularity as a measure of masculinity, as illustrated by Greek and Roman statues or the heroes of mythology (1, 38). The same emphasis on male athleticism and fitness extends from the Olympic competitions of Greece to the playing fields of English schools in the 19th century to muscular figures in early Hollywood westerns and to early American fitness magazines, such as Your Physique and Superman in the 1940s and 1950s (39, 40). By contrast, we find no comparable historical focus on male muscularity in China. Although there is a “macho” tradition in China, it is the softer, cerebral male tradition that is dominant (41). In the Chinese tradition, masculinity is comprised of both wen (translated as “mental” or “civil” and having core meanings centering around literary and cultural attainment) and wu

(translated as “mental” or “civil” and having core meanings centering around literary and cultural attainment) and wu  (“physical” or “martial” and having core meanings of martial, military, force, and power) (41, 42). It is wen masculinity, however, that has been more highly regarded (41–44). For example, for most of the past two millennia, Chinese men have aspired to the Confucian ideal of the Junzi

(“physical” or “martial” and having core meanings of martial, military, force, and power) (41, 42). It is wen masculinity, however, that has been more highly regarded (41–44). For example, for most of the past two millennia, Chinese men have aspired to the Confucian ideal of the Junzi  (gentleman, refined man, or virtuous man); in his Analects, Confucius closely associated Junzi with wen but not with wu(41, 45). Among traditional Chinese heroes and in modern Chinese literature, the cerebral male model of masculinity tends to dominate that of the macho, brawny type (41, 43). In recent Chinese books and films, masculine qualities include free-spiritedness, independence in thinking, courage, mental strength, da ye

(gentleman, refined man, or virtuous man); in his Analects, Confucius closely associated Junzi with wen but not with wu(41, 45). Among traditional Chinese heroes and in modern Chinese literature, the cerebral male model of masculinity tends to dominate that of the macho, brawny type (41, 43). In recent Chinese books and films, masculine qualities include free-spiritedness, independence in thinking, courage, mental strength, da ye  attitude (cocky, self-assured), zazhong gaoliang

attitude (cocky, self-assured), zazhong gaoliang  (suffering from knowledge of one’s unworthiness, or, in other words, humility), and the ability to harness qi

(suffering from knowledge of one’s unworthiness, or, in other words, humility), and the ability to harness qi  (46, 47). And while physical appearance does carry weight in Chinese culture, the traditional Chinese notion of Yanggang Zhiqi

(46, 47). And while physical appearance does carry weight in Chinese culture, the traditional Chinese notion of Yanggang Zhiqi  (the ideal or essence of masculinity), as illustrated by these examples, does not emphasize muscularity.

(the ideal or essence of masculinity), as illustrated by these examples, does not emphasize muscularity.

A second possible factor, which may have further widened these differences between Western and Chinese attitudes, is the influence of media images, perhaps especially in the American media (1). Widespread use of anabolic steroids in the last few decades has made it easy for male athletes, actors, and models to become leaner and more muscular than men without such chemical assistance in the past; images of these steroid-enhanced men are now common in magazines, television, and motion pictures. In addition, growing industries targeting men’s appearance regularly use such images in advertising. Preliminary data suggest that exposure to such images may cause young men to become dissatisfied with their bodies (1, 48). Taiwanese men appear to be much less exposed to muscular images than American men. For example, in the United States, men’s “health” and fitness magazines, filled with images of muscular male bodies, are ubiquitous at supermarket counters and newsstands (1, 38). In Taiwan, by contrast, there are no magazines resembling, for example, the American magazine Men’s Health(49; Kingstone Bookstore, personal communication, 2003). It is also our anecdotal observation that Taiwanese television hardly ever shows images of muscular male bodies.

A third hypothesis is that American and Chinese cultures differ in the importance of traditional male roles and that this difference in turn may have influenced attitudes toward body image. In the United States and most other Western societies, the man’s traditional roles as breadwinner, soldier, and defender of the family have declined markedly over the last generation (1, 50–52). Therefore, as we and others have suggested (1), young Western men may have increasingly focused on their bodies as one of their few remaining sources of masculine self-esteem. By contrast, the traditional male role of “head of the household” remains more intact in Chinese culture than in the West (53–58). For example, until 1997, custody of children was automatically granted to the husband in the case of a divorce, and women (if married before 1985) could not have actual ownership of property in their own names (57). A report also found that Taiwanese women worked on household chores 5.2 to 8.8 times as long as men compared to a ratio of less than 2 in the United States, Britain, and Canada (57). Indeed, the notion of zhongnan qingnu  (“men are superior, women inferior”)—a concept influenced by Confucian and Neo-Confucian traditions and the patrilocal clan system (with such characteristics as patriarchy, patrilocal residence, and patrilineality)—remains strong in Taiwan (45, 57–61).

(“men are superior, women inferior”)—a concept influenced by Confucian and Neo-Confucian traditions and the patrilocal clan system (with such characteristics as patriarchy, patrilocal residence, and patrilineality)—remains strong in Taiwan (45, 57–61).

These three hypothesized differences between Western and Chinese culture—the first long-standing and the others recent—may explain the striking contrast between the findings of our two studies in Taiwan and the findings of our previous identical studies in the United States and Europe. These cultural differences in attitudes toward male body image have direct consequences for public health in that they may explain the far greater prevalence and severity of male body image disorders and of anabolic steroid abuse in the United States and other Western countries.

A disturbing question remains: Can Chinese attitudes continue to resist the influences of Western culture? When we looked at analogous studies of female body image, the prognosis was not encouraging. A study found that women in Hong Kong typically wanted to be thinner even though they were not overweight (62). The authors concluded that a “typically ‘Western’ pattern of body dissatisfaction has overshadowed traditional Chinese notions of female beauty” (62, p. 77). Similarly, studies in Polynesia (63, 64) have found that women who were formerly content with their bodies have recently succumbed to Western ideals of thinness; for example, a prospective investigation in Fiji found striking changes in adolescent girls’ body satisfaction after only 3 years of exposure to Western television (64). These observations raise the prospect that Western notions of male body image may also be invading Chinese culture, leading to a noticeable increase in muscle dysmorphia, other body image disorders, and anabolic steroid abuse among young Chinese men in the near future. To test for this possibility, it might be useful to study body image among Taiwanese men after another 5–10 years.

|

|

|

|

Received Aug. 11, 2003; revision received March 31, 2004; accepted April 23, 2004. From the Department of Anthropology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.; and the Biological Psychiatry Laboratory, McLean Hospital/Harvard Medical School. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Pope, McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA 02478; [email protected] (e-mail). The authors thank Yu Ting Chuang, Tzu Jung Shen, Hsiu Hua Hu, Yung Hsin Chuang, Meng-Tse Lee, Ph.D., Yung Chang Chuang, Yuh Yuh Chuang, and Fei-Bin Hsiao, Ph.D., for their help with this project and Christine Tsai, Bridie Andrews, Ph.D., and Fei-Bin Hsiao, Ph.D., for their critical reading of the manuscript.

Figure 1. Difference Between the Mean Judgments of Men From Four Countries of the Muscularity of an “Average Man” and the Body “Most Preferred by Women”a

aMuscularity is expressed in units of fat-free mass index, which is a measure of the degree of muscularity (32).

1. Pope HG Jr, Phillips KA, Olivardia R: The Adonis Complex: The Secret Crisis of Male Body Obsession. New York, Free Press, 2000Google Scholar

2. Fava GA: Morselli’s legacy: dysmorphophobia (editorial). Psychother Psychosom 1992; 58:117–118Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Phillips KA, McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, Pope HG Jr, Hudson JI: Body dysmorphic disorder: 30 cases of imagined ugliness. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:302–308Link, Google Scholar

4. Phillips KA: The Broken Mirror: Understanding and Treating Body Dysmorphic Disorder. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

5. Snaith P: Body image disorders. Psychother Psychosom 1992; 58:119–124Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Pope HG Jr, Katz DL, Hudson JI: Anorexia nervosa and “reverse anorexia” among 108 male bodybuilders. Compr Psychiatry 1993; 34:406–409Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Pope HG Jr, Gruber AJ, Choi P, Olivardia R, Phillips KA: Muscle dysmorphia: an underrecognized form of body dysmorphic disorder. Psychosomatics 1997; 38:548–557Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Mangweth B, Pope HG Jr, Kemmler G, Ebenbichler C, Hausmann A, De Col C, Kreutner B, Kinzl J, Biebl W: Body image and psychopathology in male bodybuilders. Psychother Psychosom 2001; 70:38–43Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Olivardia R, Pope HG Jr, Hudson JI: Muscle dysmorphia in male weightlifters: a case-control study. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1291–1296Link, Google Scholar

10. Smith E: Bodybuilders face “flip side” of anorexia. USA Today, Nov 24, 1997, p 1Google Scholar

11. Adonis identified. Het Financieele Dagblad, Jan 11, 2001, p 14Google Scholar

12. Murphy R: Adonis man: he thinks he looks like a wimp: he’s a bodybuilder suffering from muscle dysmorphia—one of a growing number of men who believe they’ll never be “big” enough. The Mirror, Sept 26, 2002, p 36Google Scholar

13. Margo J: For Adonis, the gym is abs fabulous. Australian Financial Review, Jan 24, 2002, p 43Google Scholar

14. Ung EK, Fones CS, Ang AW: Muscle dysmorphia in a young Chinese male. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2000; 29:135–137Medline, Google Scholar

15. Blouin AG, Goldfield GS: Body image and steroid use in male bodybuilders. Int J Eat Disord 1995; 18:159–165Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Kanayama G, Gruber AJ, Pope HG Jr, Borowiecki JJ, Hudson JI: Over-the-counter drug use in gymnasiums: an underrecognized substance abuse problem? Psychother Psychosom 2001; 70:137–140Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Kanayama G, Pope HG Jr, Hudson JI: “Body image” drugs: a growing psychosomatic problem. Psychother Psychosom 2001; 70:61–65Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Kanayama G, Pope HG Jr, Cohane G, Hudson JI: Risk factors for anabolic-androgenic steroid use among weightlifters: a case-control study. Drug Alcohol Depend 2003; 71:77–86Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Handelsman DJ, Gupta L: Prevalence and risk factors for anabolic-androgenic steroid abuse in Australian high school students. Int J Androl 1997; 20:159–164Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Kindlundh AM, Isacson DG, Berglund L, Nyberg F: Factors associated with adolescent use of doping agents: anabolic-androgenic steroids. Addiction 1999; 94:543–553Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Parrott AC, Choi PY, Davies M: Anabolic steroid use by amateur athletes: effects upon psychological mood states. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 1994; 34:292–298Medline, Google Scholar

22. Thompson JK (ed): Body Image, Eating Disorders, and Obesity: An Integrative Guide for Assessment and Treatment. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1996Google Scholar

23. Buddeberg-Fischer B, Klaghofer R, Reed V: Associations between body weight, psychiatric disorders and body image in female adolescents. Psychother Psychosom 1999; 68:325–332Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Gruber AJ, Pope HG Jr, Lalonde JK, Hudson JI: Why do young women diet? the roles of body fat, body perception, and body ideal. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:609–611Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Jaeger B, Ruggiero GM, Edlund B, Gomez-Perretta C, Lang F, Mohammadkhani P, Sahleen-Veasey C, Schomer H, Lamprecht F: Body dissatisfaction and its interrelations with other risk factors for bulimia nervosa in 12 countries. Psychother Psychosom 2002; 71:54–61Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Cohane GH, Pope HG Jr: Body image in boys: a review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord 2001; 29:373–379Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Gruber AJ, Pope HG Jr, Borowiecki JJ, Cohane G: The development of the somatomorphic matrix: a bi-axial instrument for measuring body image in men and women, in Kinanthropometry VI. Edited by Norton K, Olds T, Dollman J. Sydney, Australia, International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry, 2000, pp 217–231Google Scholar

28. Pope HG Jr, Gruber AJ, Mangweth B, Bureau B, deCol C, Jouvent R, Hudson JI: Body image perception among men in three countries. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1297–1301Link, Google Scholar

29. Lynch SM, Zellner DA: Figure preferences in two generations of men: the use of figure drawings illustrating differences in muscle mass. Sex Roles 1999; 40:833–843Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Pope HG Jr, Olivardia R, Borowiecki JJ III, Cohane GH: The growing commercial value of the male body: a longitudinal survey of advertising in women’s magazines. Psychother Psychosom 2001; 70:189–192Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Jackson AS, Pollock ML: Generalized equations for predicting body density of men. Br J Nutr 1978; 40:497–504Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Kouri EM, Pope HG Jr, Katz DL, Oliva P: Fat-free mass index in users and nonusers of anabolic-androgenic steroids. Clin J Sport Med 1995; 5:223–228Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Diggle PJ, Liang K-Y, Zeger SL: Analysis of Longitudinal Data. New York, Oxford University Press, 1994Google Scholar

34. Silberstein LR, Mishkind ME, Striegel-Moore RH, Timko C, Rodin J: Men and their bodies: a comparison of homosexual and heterosexual men. Psychosom Med 1989; 51:337–346; correction, 1990; 52:479Google Scholar

35. French SA, Story M, Remafedi G, Resnick MD, Blum RW: Sexual orientation and prevalence of body dissatisfaction and eating disordered behaviors: a population-based study of adolescents. Int J Eat Disord 1996; 19:119–126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Beren SE, Hayden HA, Wilfley DE, Grilo CM: The influence of sexual orientation on body dissatisfaction in adult men and women. Int J Eat Disord 1996; 20:135–141Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. CIA World Factbook 2003: Taiwan. http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/geos/tw.htmlGoogle Scholar

38. Bordo S: The Male Body: A New Look at Men in Public and in Private. New York, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1999Google Scholar

39. Horrocks R: Male Myths and Icons: Masculinity in Popular Culture. New York, St Martin’s Press, 1995Google Scholar

40. Jackson D: Unmasking Masculinity: A Critical Autobiography. London, Unwin Hyman, 1990Google Scholar

41. Louie K: Theorising Chinese Masculinity: Society and Gender in China. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 2002Google Scholar

42. Louie K, Edwards L: Chinese masculinity: theorizing wen and wu. East Asian Hist 1995; 8:135–148Google Scholar

43. Larson W: The self loving the self: men and connoisseurship in modern Chinese literature, in Chinese Femininities, Chinese Masculinities. Edited by Brownwell S, Wasserstrom JN. Berkeley, University of California Press, 2002, pp 174–194Google Scholar

44. Perry E, Dillon N: “Little brothers” in the cultural revolution: the worker rebels of Shanghai. Ibid, pp 269–286Google Scholar

45. Confucius: The Analects. Translated by Lau DC. New York, Penguin, 1979Google Scholar

46. Chen N: Embodying qi and masculinities in post-Mao China, in Chinese Femininities, Chinese Masculinities. Edited by Brownwell S, Wasserstrom JN. Berkeley, University of California Press, 2002, pp 315–330Google Scholar

47. Zhong X: Masculinity Besieged? Issues of Modernity and Male Subjectivity in Chinese Literature of the Late Twentieth Century. Durham, NC, Duke University Press, 2000Google Scholar

48. Leit RA, Gray JJ, Pope HG Jr: The media’s representation of the ideal male body: a cause for muscle dysmorphia? Int J Eat Disord 2002; 31:334–338Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Kingstone Bookstore, Taipei, Taiwan. http://www.kingstone.com.twGoogle Scholar

50. Cottle M: Turning boys into girls. Washington Monthly, May 1998, pp 32–36Google Scholar

51. Faludi S: Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man. New York, William Morrow, 1999Google Scholar

52. Kimmel M: Manhood in America. New York, Free Press, 1996Google Scholar

53. Evans H: Past, perfect or imperfect: changing images of the ideal wife, in Chinese Femininities, Chinese Masculinities. Edited by Brownwell S, Wasserstrom JN. Berkeley, University of California Press, 2002, pp 335–360Google Scholar

54. Ni xiang zuo ge hao qizi ma? (Do you want to be a good wife?), in Funü baike daquan (xia) (Women’s Encyclopedia, vol 2). Edited by Funü zhiyou (Women’s friend). Beijing, Beifang Funü Ertong Chubanshe, 1991, pp 12–19Google Scholar

55. Shu H: Nüren bu lao dao cheng ma? (If women didn’t gossip would that be OK?). Nüxing Yanjiu (Women’s Studies) 1993; 5:61Google Scholar

56. Women, in The Republic of China 1998 Yearbook. Taipei, Government Information Office, 1998, pp 322–327Google Scholar

57. Hu J: The shifting balance of power in marriage? Translated by Williams S, Davis S. Sinorama, April 1997, pp 23–30Google Scholar

58. Ching-ju C: Where have all the daughters gone? Translated by Taylor R. Sinorama, March 1996, pp 80–88Google Scholar

59. Kelleher T: “Confucianism,” in Women in World Religions. Edited by Sharma A. Albany, State University of New York Press, 1987, pp 135–159Google Scholar

60. Chan W-T: A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1963Google Scholar

61. Raphels L: A woman who understood the rites, in Confucius and the Analects: New Essays. Edited by Van Norden B. New York, Oxford University Press, 2002, pp 275–302Google Scholar

62. Lee S, Leung T, Lee AM, Yu H, Leung CM: Body dissatisfaction among Chinese undergraduates and its implications for eating disorders in Hong Kong. Int J Eat Disord 1996; 20:77–84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Craig PL, Swinburn BA, Matenga-Smith T, Matangi H, Vaughn G: Do Polynesians still believe that big is beautiful? comparison of body size perceptions and preferences of Cook Islands, Maori and Australians. NZ Med J 1996; 109:200–203Medline, Google Scholar

64. Becker AE, Burwell RA, Gilman SE, Herzog DB, Hamburg P: Eating behaviours and attitudes following prolonged exposure to television among ethnic Fijian adolescent girls. Br J Psychiatry 2002; 180:509–514Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar