Personality Dimensions in First-Episode Psychoses

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors compared the patterns and specificity of premorbid personality dimensions in first-episode schizophrenia patients with those in patients with first-episode nonschizophrenia psychoses and healthy comparison subjects. METHOD: A series of 63 patients with first-episode schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, 34 patients with first-episode nonschizophrenia psychoses, and 77 healthy comparison subjects were assessed with the Personality Disorder Evaluation, a semistructured interview schedule that measures personality dimensions. RESULTS: Cluster A as well as cluster C dimensional scores—in particular, the avoidant personality score—were higher for the schizophrenia patients, and cluster B dimensional scores were higher for the patients with nonschizophrenia psychoses. Cluster C dimensional scores, particularly the avoidant personality score, were highly intercorrelated with all cluster A dimensional scores. CONCLUSIONS: The observed association between avoidant personality and schizophrenia supports the recent literature on the comorbidity of nonspectrum personality disorders in schizophrenia. This association may be related to shared neurodevelopmentally mediated impairments in social cognition in schizophrenia and some cluster C personality dimensions.

Nearly a century ago, Hoch (1) proposed a relationship between a withdrawn, detached personality type and the development of schizophrenia. This dimension of personality was conceptualized as “schizoidea” or schizoid personality by Bleuler (2), Kraepelin (3) and Kretschmer (4). Schizoid temperament, according to Kretschmer, existed on a continuum ranging from being cold and insensitive to being “nervously sensitive.” Expanding beyond these conceptualizations of schizoid traits, Meehl (5) posited a model of personality organization reflecting the latent liability to schizophrenia, namely schizotypy, that included the four fundamental symptoms of cognitive slippage, interpersonal aversiveness, anhedonia, and ambivalence. Subsequently, a genetic basis for both schizotypal personality and schizophrenia was proposed (6–9), and the neurodevelopmental hypothesis took the center stage in explaining what came to be known as the spectrum concept of schizophrenia (7). Over the years, this spectrum has been variously defined. The broadest definition included, besides other entities, all the three cluster A personality disorders (schizoid, paranoid, and schizotypal), and the narrowest definition was restricted to schizotypal personality disorder (10).

A plethora of clinical lore exists on the association of schizophrenia with DSM-based cluster A personality disorders, especially schizoid personality disorder and schizotypal personality disorder. Although the occurrence of other “nonspectrum” personality disorders in schizophrenia had been anecdotally reported (11, 12), this area never garnered sufficient attention, presumably because the neurodevelopmental approach usually biased researchers to a priori select the so-called schizophrenia spectrum personality disorders for study. However, more recent literature associating cluster C personality disorders with schizophrenia has rekindled interest in exploring this area further (13). Only a handful of studies have examined personality disorders in the early course of schizophrenia, but these studies had methodologic limitations, including small numbers of subjects, lack of a healthy comparison group, nonblinding to axis I diagnoses, examination of a single diagnostic group (which precludes comment on specificity of the findings), and failure to use structured clinical interviews (for citations, see reference 14).

In an effort to overcome these shortcomings, we examined the patterns and specificity of personality disorders in first-episode schizophrenia patients, compared with patients with first-episode nonschizophrenia psychoses and healthy comparison subjects. By examining personality disorders in psychosis of recent onset, we hoped to avoid the potential confounding effect of chronic illness on personality traits. These patients were assessed in a semistructured interview with the Personality Disorder Evaluation (15, 16) after stabilization of their psychotic symptoms, typically after 3–4 weeks of antipsychotic drug treatment, in order to avoid the potential confounding influence of the psychotic state on the personality parameters. In keeping with previous reports, we hypothesized that more cluster A personality features would be found in patients with schizophrenia and more cluster B personality features would be found in patients with nonschizophrenia psychotic disorders, including bipolar disorder and depressive disorders. Another aim of this study was to test the reported association of cluster C personality disorders with schizophrenia (13). We gathered data from healthy comparison subjects to enhance the specificity of our findings.

Method

Subjects

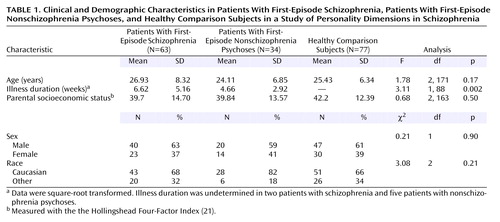

A series of 63 treatment-naive patients with first-episode schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders (schizophrenia [N=43], schizoaffective disorder [N=8], and schizophreniform disorder [N=12]), 34 treatment-naive patients with first-episode nonschizophrenia psychoses (delusional disorders [N=8], bipolar disorder with psychotic features [N=7], major depression with psychotic features [N=11], brief psychotic disorder [N=1], and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified [N=7]), and 77 healthy comparison subjects were included in the study. All subjects provided written informed consent after complete description of the study. Demographic data, including parental socioeconomic status, were collected by using a structured interview. The patients’ diagnoses were determined at consensus conference meetings of senior diagnostician/clinical researchers (M.S.K., G.L.H., C.C., N.R.S.) approximately 1 month after the patients’ study entry. All available clinical information and the data gathered with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (17) were used in making the diagnoses. All diagnoses were reconfirmed at consensus meetings by using DSM-IV criteria. During these meetings, each patient’s illness duration was also determined by consensus after a review of historical information about psychosis onset. Exclusion criteria were medical illness affecting the central nervous system function, prior neuroleptic treatment, and IQ lower than 75. None of the patients met the criteria for a DSM-IV substance use disorder currently or within the previous 6 months. These patients continue to participate in a longitudinal, prospective study that includes careful diagnostic rereview to evaluate diagnostic stability (18). Positive and negative symptoms were rated at baseline and at 4 weeks by using the Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) and the Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS), respectively (19). We also computed positive symptom, negative symptom, and disorganization dimensional scores derived from the SAPS and SANS, as done by other investigators (20). Interrater reliability (for ratings by N.M.M., D.M.M., and G.L.H) was maintained through monthly rater meetings led by a senior clinician (G.L.H.); the intraclass correlation coefficients for the various assessment scales used by these raters were >0.80.

The healthy comparison subjects were recruited by advertisement in local neighborhoods and communities in which the patients resided. Exclusion criteria were any lifetime history of axis I psychiatric disorder, any exposure to psychotropic drugs within the previous 6 months, history of neurologic disorders or any other chronic medical problems with potential to influence CNS function, and IQ less than 75. None of the comparison subjects had a lifetime history of substance abuse or dependence. After an initial telephone screening, these subjects were interviewed by a senior clinician (M.S.K., E.R., or G.L.H.) using the SCID (nonpatient version). Healthy comparison subjects were matched, as a group, with the schizophrenia patients for age, gender, race, and parental socioeconomic status measured with the Hollingshead Four-Factor Index (21).

Personality Assessments

Personality assessments were carried out by a trained clinician (N.M.M.) typically 3–4 weeks after the initial evaluation and after stabilization of the patient’s acute psychotic symptoms. The same clinician performed all the assessments. The Personality Disorder Evaluation (15), a semistructured instrument designed to systematically survey the phenomenology and life experiences relevant to the diagnosis of all the DSM-III-R personality disorders, was used. It is a comprehensive and reliable evaluation for assessing personality disorders (22, 23). The assessments were typically carried out before the consensus diagnostic conferences were held; the clinician was therefore unaware of the consensus diagnoses at the time of the personality assessment.

Statistical Analyses

First, the variables were examined for normality by using the Shapiro-Wilks test. Normally distributed data, such as age and socioeconomic status, were compared by using analysis of variance (ANOVA), and categorical measures, such as gender, were compared by using chi-square tests. Since the Personality Disorder Evaluation variables were not normally distributed (all Shapiro-Wilks W values >0.6, p<0.01), Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA was performed for each of the personality dimensions, with diagnostic group (patients with schizophrenia, patients with nonschizophrenia psychoses, and healthy comparison subjects) as the grouping variable. Post hoc comparisons (median test) were then used to examine pairwise group differences. Spearman’s correlations were carried out to examine the relationships between Personality Disorder Evaluation dimensional scores across clusters. To address multiple comparisons, the alpha was set at p<0.001. Two-tailed p values were computed in all analyses.

Results

Table 1 shows the clinical and demographic features of the three groups. As Table 2 shows, all three personality dimension clusters showed significant differences (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVAs and planned comparisons). Cluster A dimension scores were significantly higher in the schizophrenia group, and cluster B dimension scores were higher in the group with nonschizophrenia psychoses. Cluster C dimension scores were higher in both groups of patients but were more prominent in the schizophrenia group. In particular, the avoidant personality dimension score was significantly higher in the schizophrenia group, compared to the group with nonschizophrenia psychoses. We also looked at the frequency of axis II diagnostic categorizations derived from the Personality Disorder Evaluation data across the three groups. Schizotypal personality disorder and avoidant personality disorder were significantly more frequent in the schizophrenia patients, and borderline personality disorder was more frequent in the nonschizophrenia psychoses group (Table 3).

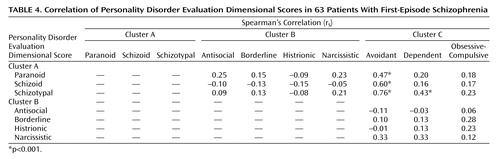

Significant intercluster correlations were found between schizoid and avoidant, schizotypal and avoidant, paranoid and avoidant, and schizotypal and dependent personality dimensions (Table 4). It is noteworthy that the avoidant personality dimension correlated with all cluster A personality dimensions.

None of the correlations between Personality Disorder Evaluation scores and baseline psychopathological measures reached significance in the schizophrenia group. However, the paranoid and schizotypal Personality Disorder Evaluation dimensional scores of schizophrenia group showed positive correlations with disorganization scores at week 4 (Table 5). For patients with any psychotic disorder (schizophrenia or a nonschizophrenia psychosis), positive correlations were found between paranoid personality dimensional scores and baseline positive symptoms scores and also between paranoid, schizotypal, and avoidant personality dimensional scores and week 4 disorganization scores (Table 5).

Discussion

The main findings of our study include the predicted higher level of cluster A characteristics among the first-episode schizophrenia patients and the predicted higher level of cluster B characteristics in the patients with first-episode nonschizophrenia psychoses. These findings are similar to those of earlier studies (14, 24–26). Our observations provide some validation of the current approach to classifying personality disorders. Of particular clinical interest was the higher level of cluster C personality disorder characteristics in schizophrenia patients. In concert with previous developments in this area of research (13), the main focus of our discussion is on personality disorders in first-episode/recent-onset schizophrenia and the association of cluster C personality disorders with schizophrenia.

Although previous studies have examined personality dimensions in first-episode schizophrenia, to our knowledge our study is the first study to examine these traits in patients with psychotic disorders in comparison with healthy comparison subjects. It is difficult to compare our results with those of the few other studies that have carried out structured assessment of personality disorders in first-episode/recent-onset schizophrenia, primarily because of differences in illness characteristics (duration of illness, medication status), methods of collecting the data (patient versus informant interviews), dimensional and categorical approaches to personality, and the instruments used for assessing the personality domains. Cuesta el al. (27) recently reported on personality dimensions in first-episode psychosis but used different tools to assess both personality dimensions and psychopathology. Hogg et al. (28) showed that schizotypal, antisocial, and borderline personality disorders were the most common personality disorders in schizophrenia on the basis of informant interviews with the Structured Interview for DSM-III Personality Disorders but that dependent, narcissistic, and avoidant personality disorders were the most common personality disorders on the basis of data from a self-report inventory. However, the authors found little agreement between the two instruments. Another study that used the Structured Interview for DSM-III Personality Disorders reported an association of schizotypal and antisocial personality disorders with schizophrenia (29). One limitation of these previous studies was that the investigators were not blind to the main psychiatric diagnosis and/or to clinical information about the patients. This limitation assumes importance in light of the finding of Bernstein et al. (30) that the prevalence of cluster A personality disorders was significantly lower when the rater was blind to patients’ clinical information than when the rater was not. A study from the United Kingdom that used a semistructured interview to rate premorbid personality according to ICD-9 classifications demonstrated that premorbid schizoid, paranoid, and explosive traits were more common in patients with schizophrenia than in patients with other nonorganic psychoses (14). However, the instrument used did not cover all items included in the DSM-III/DSM-III-R conceptualization of personality disorders. Using a structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R personality disorders, Solano and DeChavez (13) showed that the most common personality disorders in patients with schizophrenia, in order of frequency, were avoidant, schizoid, paranoid, dependent, and schizotypal personality disorders. They also showed that almost 50% of the 40 schizophrenia patients in their study had two or more personality disorders. In addition, avoidant personality disorder significantly correlated with schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders, as shown by our study. One limitation of this study was the lack of comparison with patients with nonschizophrenia psychoses or with healthy subjects.

Another finding of our study was the correlation between paranoid, schizotypal, and avoidant personality dimensions and the disorganization dimension of psychosis 4 weeks after intake. Thought disorder, which is a part of the disorganization dimension, has been proposed as a marker of familial vulnerability to schizophrenia (a trait marker) (31), and thus it may have persisted after the stabilization of acute psychotic symptoms. The correlation between cluster C personality dimensions and the disorganization dimension of psychosis has been shown in a previous study (32). This study showed that passive-dependent personality dimensions (which have some similarity to cluster C traits) were associated with the disorganization dimension of psychosis. However, our finding of a lack of correlation between personality dimensions and negative symptoms differs from that of a previous study of personality dimensions in first-episode psychosis, in which higher scores on the schizoid dimension were related to more severe negative symptoms (27). This difference may be due to difference in the scales used to assess psychopathology, as the disorganization dimension is better represented by the SAPS and SANS than by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, which was used in the previous study (27, 33).

In light of the literature on personality disorders in schizophrenia, the finding of a higher frequency of nonspectrum personality disorders in schizophrenia raises some interesting questions. First, is there a theoretical basis for the occurrence of nonspectrum personality disorders in schizophrenia? Second, can the neurodevelopmental hypothesis, which has traditionally supported schizophrenia as an extension of schizoid or schizotypal personality disorders (7, 32), explain the occurrence of nonspectrum personality disorders in this disorder? Addressing the first issue, we take a brief look at the historical concept of schizoid personality disorder. Kretschmer’s conceptualization of schizoid temperament consisted of two variants: the hyperaesthetic type and the anesthetic type characterized by hypersensitivity and insensitivity in social context, respectively (4). These categories have some similarities with the present-day avoidant and schizoid personality disorders. Kretschmer also reported combinations of these variants and transition from one to another. This relationship between some cluster A and cluster C personality types also existed before DSM-III, as the conceptualization of schizoid personality disorder then included features of what are now known as schizotypal and avoidant personality disorders. Later, the core feature promulgated to differentiate schizoid personality disorder from avoidant personality disorder was the extent to which the individual desired social contact versus the extent to which the individual was indifferent to social contact. However, this trait is considered by some authors to exist on a continuum (34), which is consistent with our and others’ observations of an association between these two personality disorders (13, 35, 36). This association between cluster A and cluster C personality disorders is further bolstered by a factor analytic study of personality traits in which the DSM-III-R-defined schizoid, schizotypal, and avoidant personality disorders were found to be represented by a single common factor—social avoidance (37). Together, these findings suggest that nonspectrum personality disorders, especially cluster C avoidant personality disorder, may be an important axis-II comorbidity in schizophrenia-like psychosis. This comorbidity may occur because of similarities between the symptoms of cluster A personality disorders and those of avoidant personality disorder. However, if similarity were the sole explanation of the comorbidity, we would have expected the strongest correlation between the schizoid personality and avoidant personality dimensions, as these two differ mainly in the aspect of desire (or lack of desire) to have social contact. The strong correlation between the dimensions of schizotypal personality, which is regarded as the core spectrum personality type associated with schizophrenia, and the avoidant personality dimensions may indicate that the latter possesses trait-like characteristics similar to the traditional spectrum personality disorders. Deciphering this relationship would require more elaborate studies involving relatives of patients with schizophrenia and high-risk populations.

A theoretical framework for the occurrence of nonspectrum personality disorders in schizophrenia is better understood by the dimensional concept of schizotypy, wherein positive schizotypy represents the psychosis-like traits, while negative schizotypy represents the schizoid-avoidant traits (38). This relationship is also supported by the finding from the Roscommon Family study that avoidant symptoms were the only factor in schizotypy to distinguish relatives of probands with schizophrenia from relatives of probands with psychotic affective illness (35). Meehl’s conceptualization of schizotypy (5) includes the symptom of “social aversiveness,” characterized by social fear, expectation of rejection, and conviction of one’s unlovability, which is reminiscent of the present-day conceptualization of avoidant and dependent personality disorders. An alternative explanation of cluster C comorbidity in schizophrenia is one of etiological heterogeneity in schizophrenia, with the “nongenetic” type preceded by a normal premorbid personality or associated with nonspectrum personality disorders and the “genetic” type preceded by spectrum personality disorders (13, 39). However, to date, the search for such etiological subtypes of schizophrenia has not been fruitful (10, 40).

Literature on the interaction between the contemporary psychosocial and neurobiological models of the pathogenesis of schizophrenia suggest neurodevelopmental insults to brain regions responsible for social cognition, including the basal ganglia, amygdala, and orbitofrontal cortex (41). The concept of social cognition includes dimensions of attachment, social anxiety, sensitivity, and social avoidance, which represent the very domains affected in avoidant and dependent personality disorders (37). Thus, there exists some evidence to support a neurodevelopmental basis for the occurrence of some cluster C personality disorders in schizophrenia. A hypothetical mechanism could be that the neurodevelopmentally induced cognitive deficits related to social tasks may overwhelm a vulnerable individual when the latter meets the demands of “secondary socialization” (42), which occurs during adolescence and early adulthood, the typical age for the shaping of adult personality and also for the onset of schizophrenia. This interpretation is supported by the association of certain personality domains with poor performance on cognitive tasks. For instance, patients with psychosis who have passive-dependent traits have been shown to have poorer cognitive performance on memory tasks (43). Another study showed that first-degree relatives of schizophrenia patients who scored high on the disorganization dimension of schizotypy had more incorrect responses on a continuous performance test (44). This cognitive deficit occurs because of failure to suppress the incorrect responses, a feature of orbitofrontal dysfunction, which is also implicated in impaired social cognition in schizophrenia (41, 44). Taken together, these findings suggest that the putative association of cognitive dysfunction and personality dimensions favors a neurobiological basis of personality-cognitive impairment in psychosis, as hypothesized by some authors (43). Because our study had a cross-sectional design, we cannot speculate about whether personality dimensions have a pathogenetic influence on the development of psychosis, although compelling evidence gleaned from longitudinal studies, studies of high-risk populations, and family studies suggests that personality dimensions may be a predisposing factor for psychosis (see references 30 and 32). Other competing models pertaining to the relationship between personality and psychosis include personality disorder as an attenuated form of psychotic disorder, the pathoplastic effects of personality on psychopathology, and personality disorder as a complication of a psychotic disorder. Several authors have discussed these models at length (27, 45).

Although this discussion has mainly focused on cluster C personality disorders in schizophrenia, some investigators have found associations involving other personality disorders, particularly an association between antisocial personality disorder/sociopathic traits and schizophrenia (20, 28, 29). Our observations are also consistent with these findings. We observed higher levels of the cluster B dimensions in the schizophrenia group, compared to the healthy subjects, but the patients with nonschizophrenia psychoses had significantly higher scores in all the cluster B dimensions except antisocial personality, compared to the schizophrenia patients. The differential association of cluster A dimensions with schizophrenia-like psychosis and of cluster B dimensions with affective psychosis may partly be explained by commonalities in the neurobiology of these conditions. For example, increased dopaminergic function in schizotypal personality disorder has been related to psychosis-like symptoms in this personality disorder, and abnormalities in the serotonergic system have been found in individuals with borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder (46). More studies are needed to decipher any neurobiological similarities between cluster C personality types and schizophrenia.

The strengths of our study consist of the inclusion of a relatively large, well-characterized group of first-episode schizophrenia patients, the inclusion of both a group of patients with first-episode nonschizophrenia psychoses and a healthy comparison group, and the use of a standard approach to personality assessments by a rater who was blind to diagnostic categorization. This study also has some potential limitations. First, it is difficult to be certain that the clinician who administered the Personality Disorder Evaluation was completely blind to the diagnostic group of the interviewee. However, personality evaluations were typically conducted before the consensus diagnostic meetings. Second, although the condition of many patients had stabilized, some continued to have psychotic symptoms, which raises the question of whether the Personality Disorder Evaluation ratings were “colored” by concomitant symptoms of an axis I disorder. To overcome this potential problem of confounding “trait” and “state,” Personality Disorder Evaluation dimensions were correlated with psychopathology assessed at baseline and also at 4 weeks, when we expected the acute psychotic symptoms to start remitting. A better strategy to separate the influence of axis I disorders on the presentation of axis II symptoms, however, is to prospectively study subjects with high risk for schizophrenia. However, besides being time consuming and laborious, such a strategy may not result in the full distinction of prodromal symptoms from premorbid personality traits, because symptoms of the schizophrenia prodrome overlap with those of schizotypal personality disorder (47). Third, the possibility of biased retrospective recall and the lack of corroborative information from subjects’ relatives, as highlighted in previous studies of personality disorders (30, 45, 48), is also relevant to this study. Fourth, we did not have the data to ascertain the duration of personality traits experienced by the subjects, and none of the existing personality inventories allows quantification of the individual traits. In future studies, such data should be carefully collected from patients early in the course of psychotic disorders. Finally, the observed association of cluster B traits in nonschizophrenia psychoses needs to be interpreted with caution because of the comparatively small number of subjects and heterogeneity of the group.

In conclusion, this study confirms and extends the previously reported association of nonspectrum personality disorders with schizophrenia and attempts to explore the theoretical and pathophysiological bases for the correlation between nonspectrum personality disorders and the traditional schizophrenia spectrum personality disorders. More systematic research is required to replicate these findings and to further elucidate the relationship of some cluster C personality disorders with psychopathology, cognitive functioning, and outcome in schizophrenia.

|

|

|

|

|

Received Nov. 17, 2003; revision received Feb. 19, 2004; accepted March 4, 2004. From the Department of Psychiatry, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine; and the Psychiatry Research Department, Zucker-Hillside Hospital, Glen Oaks, N.Y. Address correspondence and reprint requests Dr. Keshavan, UPMC Health System-Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Room 441, 3811 O’Hara St., Pittsburgh, PA., 15213; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by NIMH grants MH-45203, MH-01180, and MH-45156 (Dr. Keshavan) and NIH general clinical research center grant M01 RR-00056. The authors thank Kevin Eklund, Dr. Cameron Carter, and Dr. Elizabeth Radomsky for help with subject recruitment and clinical assessment.

1. Hoch A: Constitutional factors in the dementia praecox group. Rev Neurol Psychiatry 1910; 8:463–474Google Scholar

2. Bleuler E: Textbook of Psychiatry. New York, Macmillan, 1924Google Scholar

3. Kraepelin E: Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia (1919). Translated by Barclay RM; edited by Robertson GM. New York, Robert E Krieger, 1971Google Scholar

4. Kretschmer E: A Textbook of Medical Psychology. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 1934Google Scholar

5. Meehl PE: Schizotaxia, schizotypy, schizophrenia. Am Psychol 1962; 17:827–838Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Kety SS, Rosenthal D, Wender PH, Schulsinger F: The types and prevalence of mental illness in the biological and adoptive families of adopted schizophrenics. J Psychiatr Res 1968; 1:345–362Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Mednick SA, Parnas J, Schulsinger F: The Copenhagen High-Risk Project, 1962–1986. Schizophr Bull 1987; 13:485–495Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Gottesman II, Shields J: Schizophrenia and Genetics: A Twin Study Vantage Point. New York, Academic Press, 1972Google Scholar

9. Kendler KS, McGuire M, Gruenberg AM, Spellman M, O’Hare A, Walsh D: The Roscommon Family Study, II: the risk of nonschizophrenic nonaffective psychoses in relatives. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:645–652Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Lichtermann D, Karbe E, Maier W: The genetic epidemiology of schizophrenia and of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2000; 250:304–310Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Arieti S: Interpretation of Schizophrenia, 2nd ed. New York, Basic Books, 1974Google Scholar

12. Bleuler M: The Schizophrenia Disorders: Long-Term Patient and Family Studies. New Haven, Conn, Yale University Press, 1978Google Scholar

13. Solano JJ, DeChavez MG: Premorbid personality disorders in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2000; 44:137–144Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Dalkin T, Murphy P, Glazebrook C, Medley I, Harrison G: Premorbid personality in first-onset psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 164:202–207Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Loranger AW, Susman VL, Oldham JM, Russakoff LM: The Personality Disorder Examination: a preliminary report. J Personal Disord 1987; 1:1–13Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Loranger A, Lenzenweger M, Gartener A, Susman V, Herzig J, Zammit G, Gartner J, Abrams R, Young R: Trait-state artifacts and the diagnosis of personality disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:720–728Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P), version 2. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

18. Keshavan MS, Schooler NR: First-episode studies of schizophrenia: criteria and characterization. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:491–513Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Andreasen NC: Methods for assessing positive and negative symptoms. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry 1990; 24:73–88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Cuesta MJ, Peralta V, Caro F: Premorbid personality in psychoses. Schizophr Bull 1999; 25:801–811Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Hollingshead AB: Four-Factor Index of Social Status. New Haven, Conn, Yale University, Department of Sociology, 1975Google Scholar

22. Lenzenweger MF: Psychometric high-risk paradigm, perceptual aberrations, and schizotypy: an update. Schizophr Bull 1994; 20:121–135Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Zimmerman M: Diagnosing personality disorders: a review of issues and research methods. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:225–245Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Akiskal HS, Hirschfeld RM, Yerevanian BI: The relationship of personality to affective disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:801–810Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Pica S, Edwards J, Jackson HJ, Bell RC, Bates GW, Rudd RP: Personality disorders in recent-onset bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry 1990; 31:499–510Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Turley B, Bates GW, Edwards J, Jackson HJ: MCMI-II personality disorders in recent-onset bipolar disorders. J Clin Psychol 1992; 48:320–329Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Cuesta MJ, Gil P, Artamendi M, Serrano JF, Peralta V: Premorbid personality and psychopathological dimensions in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res 2002; 58:273–280Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Hogg B, Jackson HJ, Rudd RP, Edwards J: Diagnosing personality disorders in recent-onset schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis 1990; 178:194–199Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Jackson HJ, Whiteside HL, Bates GW, Bell R, Rudd RP, Edwards J: Diagnosing personality disorders in psychiatric inpatients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991; 83:206–213Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Bernstein DP, Kasapis C, Bergman A, Weld E, Mitropoulou V, Horvath T, Klar HM, Silverman J, Siever LJ: Assessing axis II disorders by informant interview. J Personal Disord 1997; 11:158–167Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Hain C, Maier W, Hoeschst-Janneck S, Franke P: Subclinical thought disorder in first-degree relatives of schizophrenic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1995; 92:305–309Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Peralta V, Cuesta MJ, deLeon J: Premorbid personality and positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991; 84:336–339Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Cuesta MJ, Peralta V: Psychopathological dimensions in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1995; 21:473–482Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Alden LE, Laposa JM, Taylor CT, Ryder AG: Avoidant personality disorder: current status and future directions. J Personal Disord 2002; 16:1–29Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Kendler KS, McGuire M, Gruenberg AM, Walsh D: Schizotypal symptoms and signs in the Roscommon Family Study: their factor structure and familial relationship with psychotic and affective disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:296–303Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Jorgensen A, Parnas J: The Copenhagen High-Risk Study: premorbid and clinical dimensions of maternal schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis 1990; 178:370–376Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Schroeder ML, Livesley WJ: An evaluation of DSM-III-R personality disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991; 84:512–519Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Venables PH, Rector NA: The content and structure of schizotypy: a study using confirmatory factor analysis. Schizophr Bull 2000; 26:587–602Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Meehl PE: Toward an integrated theory of schizotaxia, schizotypy, schizophrenia. J Personal Disord 1990; 4:1–99Crossref, Google Scholar

40. Tsuang M: Schizophrenia: genes and environment. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 47:210–220Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Keshavan MS, Hogarty GE: Brain maturational processes and delayed onset in schizophrenia. Dev Psychopathol 1999; 11:525–543Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Carter MJ, Flesher S: The neuro-sociology of schizophrenia: vulnerability and functional disability. Psychiatry 1995; 58:209–224Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Cuesta MJ, Peralta V, Zarzuela A: Are personality traits associated with cognitive disturbance in psychosis? Schizophr Res 2001; 51:109–117Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Vollema MG, Postma B: Neurocognitive correlates of schizotypy in first degree relatives of schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Bull 2002; 28:367–377Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Hulbert CA, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD: The relationship between personality and course and outcome in early psychosis: a review of literature. Clin Psychol Rev 1996; 16:707–727Crossref, Google Scholar

46. Phillips KA, Yen S, Gunderson JG: Personality disorders, in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Clinical Psychiatry, 4th ed. Edited by Hales RE, Yudofsky SC. Arlington, Va, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2003, pp 803–832Google Scholar

47. Squires-Wheeler E, Skodol AE, Erlenmeyer-Kimling L: The assessment of schizotypal features over two points in time. Schizophr Res 1992; 6:75–78Crossref, Google Scholar

48. Zimmerman M, Pfohl B, Coryell W, Stangl D, Corenthal C: Diagnosing personality disorder in depressed patients: a comparison of patient and informant interviews. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:733–737Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar