Extent and Cost of Informal Caregiving for Older Americans With Symptoms of Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to obtain nationally representative estimates of the additional time and cost associated with informal caregiving for older Americans with depressive symptoms. METHOD: Data from the 1993 Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old Study, a nationally representative survey of people age 70 years or older (N=6,649), were used to determine the weekly hours and imputed costs of informal caregiving for elderly people with no depressive symptoms in the last week, one to three depressive symptoms in the last week, and four to eight depressive symptoms in the last week. RESULTS: Forty-four percent of survey respondents reported one to three depressive symptoms, and 18% reported four to eight depressive symptoms. In multivariate regression analyses that adjusted for sociodemographics, caregiver network, and coexisting chronic health conditions, respondents with no depressive symptoms received an average of 2.9 hours per week of informal care, compared with 4.3 hours per week for those with one to three symptoms and 6.0 hours per week for those with four to eight symptoms. Caregiving associated with depressive symptoms in elderly Americans represented a yearly cost of about $9 billion. CONCLUSIONS: Depressive symptoms in elderly persons are independently associated with significantly higher levels of informal caregiving, even after the effects of major coexisting chronic conditions are adjusted. The additional hours of care attributable to depressive symptoms represent a significant time commitment for family members and, therefore, a significant societal economic cost. Further research should evaluate the causal pathways by which depressive symptoms lead to high levels of caregiving and should examine whether successful treatment of depression reduces the need for informal care.

Symptoms of depression may cause or exacerbate physical disability in older individuals (1–7) and may do so to a greater extent than other common chronic diseases such as hypertension, arthritis, heart disease, and diabetes (8–12). The World Health Organization estimated that major depressive disorder was the fourth leading cause of disability in 1990, and it is projected to become the second leading cause of disability (behind heart disease) in the coming decades (13, 14). Depressive symptoms may also exacerbate cognitive impairment in elderly persons (15–17), leading to further limitations in independent functioning, and, therefore, increased need for caregiving and supervision from family members (18, 19).

Depressive symptoms are quite common among older individuals living in the community. Among individuals age 60 years or older, the reported prevalence of major depressive disorder ranges from 1% to 5% and the reported prevalence of significant but milder depression ranges from 7% to 23% (20–22). Compared to younger depressed adults, older individuals may be more likely to report “anhedonia” (i.e., markedly diminished interest or pleasure in usual activities) and somatic complaints (e.g., fatigue and pain) (23). These specific depressive symptoms may be less likely to be detected or treated by health care providers (24–26).

Depressive symptoms are associated with greater impairment and decreased quality of life among patients with coexisting chronic illnesses, such as emphysema (27), cancer (28), and diabetes (29). When depression coexists with other medical conditions, the resulting disability appears to be additive (10, 30).

In addition to their substantial negative effect on individuals’ independent functioning and quality of life, depressive symptoms are associated with high economic costs to both patients and insurers. Depressed individuals, including depressed elderly persons, use two to three times as many medical services as people who are not depressed (29, 31–33). Depressed individuals are also more likely to miss time from work, further increasing the societal economic burden attributable to depressive symptoms (8, 9, 11).

Little is known, however, about the extent to which depressive symptoms lead to increased use of unpaid care from family members and friends (informal caregiving). The economic value of such informal caregiving is substantial in other chronic medical conditions such as dementia (19, 34) and cancer (35), and the total economic value of informal caregiving in the United States in 1997 was estimated to be $196 billion, or more than twice the amount paid for nursing home care (36). If informal caregiving costs for depressive symptoms are substantial, their exclusion from analyses of the total cost of depression will result in an underestimation of the true societal impact of depression and an undervaluing of the cost-effectiveness of interventions to treat depressive symptoms (37, 38).

Given the high prevalence of depressive symptoms among older individuals, the negative effect of those symptoms on independent functioning, the existence of effective treatments for depressive symptoms (39), and the rapidly aging U.S. population, a fuller understanding of the extent to which depressive symptoms among older persons may lead to informal caregiving is needed. We used data from a nationally representative population-based sample of older Americans to determine the association of depressive symptoms with limitations in independent functioning and to calculate the additional time and related costs associated with informal caregiving to address those limitations. To our knowledge, this is the first study of the extent and costs of informal caregiving for depressive symptoms in older Americans.

Method

Data Source

We used data from the baseline survey (1993) of the Asset and Health Dynamics among the Oldest Old (AHEAD) cohort of the Health and Retirement Study (40). The Health and Retirement Study is a nationally representative longitudinal survey of adults conducted by the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan with funding from the National Institute on Aging. AHEAD respondents included 7,443 people age 70 years or older at the time of the baseline interview (i.e., born in 1923 or before). Interviews were conducted in person or over the telephone in English or Spanish. Proxy respondents were interviewed if the selected respondent was unable to answer the survey questions independently. A response rate of 80.4% was achieved.

Identification of Depressive Symptoms

Each respondent was asked to answer “yes” or “no” to the following eight statements taken from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D Scale) (41): Much of the time during the past week: 1) I felt depressed, 2) I felt that everything I did was an effort, 3) my sleep was restless, 4) I was happy, 5) I felt lonely, 6) I enjoyed life, 7) I felt sad, and 8) I could not “get going.” For each respondent, the number of “yes” responses to statements 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8 and the number of “no” responses to statements 4 and 6 were summed to arrive at a total depressive symptom score that ranged from 0 to 8. Survey respondents were then sorted into three mutually exclusive categories on the basis of their total depressive symptom score: 1) no depressive symptoms, 2) one to three depressive symptoms, and 3) four to eight depressive symptoms. This abbreviated 8-item version of the CES-D Scale has comparable reliability and validity to the widely used and validated 20-item CES-D Scale (41–43). Further information regarding the comparability of the 20-item and 8-item CES-D Scales has been published previously (44).

The AHEAD study identified proxy respondents for individuals unable or unwilling to complete the survey by themselves (40). Approximately 10% of AHEAD respondents were represented by a proxy and so could not be asked the CES-D Scale questions. This analysis includes only self-respondents (N=6,649), since answers to the CES-D Scale items were not available for respondents represented by a proxy.

Identifying Limitations in Independent Functioning

An individual was considered to have a limitation in activities of daily living (i.e., eating, transferring, toileting, dressing, bathing, walking across a room) if he or she reported having “difficulty,” using mechanical assistance (e.g., a walker or wheelchair) or receiving help with any of the six activities of daily living. An individual was considered to have a limitation in instrumental activities of daily living (i.e., preparing meals, grocery shopping, making phone calls, taking medications, managing money) if he or she reported needing help with or not performing an instrumental activity of daily living because of a health problem (45).

Caregiving Hours

Respondents were identified as recipients of informal care if 1) a relative or unpaid nonrelative (with no organizational affiliation) provided in-home assistance with any activity of daily living “most of the time” and/or 2) a relative or unpaid nonrelative (with no organizational affiliation) provided in-home assistance with any instrumental activity of daily living because of a health problem (45).

The number of hours per week of informal care was calculated by using the average number of days per week and the average number of hours per day that the respondent reported receiving assistance from informal caregivers during the prior month. The method used for calculating weekly hours of care from the AHEAD data has been described previously (46, 47).

Potential Confounding Variables

Since the goal of the analysis was to quantify the additional hours of informal caregiving attributable to depressive symptoms, we controlled for the presence of other comorbid chronic health conditions that might independently lead to the receipt of informal care, as well as for sociodemographic characteristics (age, race, gender, net worth) and the availability of informal caregivers (having a spouse present, having a living adult child). The chronic (self-reported) health conditions controlled for in the study included heart disease, stroke, diabetes, hypertension, lung disease, urinary incontinence, cancer, and arthritis. In addition, we controlled for the presence of visual impairment (corrected eyesight reported as fair, poor, or legally blind) and hearing impairment (corrected hearing reported as fair or poor). Finally, we also adjusted for the presence of cognitive impairment consistent with dementia as measured by a previously validated cognitive status instrument (19, 48).

Although we examined the bivariate relationship of depressive symptoms with limitations in activities of daily living and in instrumental activities of daily living, we did not control for the number of those limitations in the multivariate regression analysis. Limitations in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living were considered the mediating factors between depressive symptoms and informal caregiving (i.e., depressive symptoms led to the limitations, which, in turn, led to the receipt of informal caregiving to address the limitations), so controlling for these variables in the regression analysis would result in an underestimation of the true effect of depressive symptoms on the quantity of informal caregiving (49). To control for limitations in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living related to other chronic conditions besides depression, we included variables in the analysis to indicate the presence of these coexisting illnesses.

Calculating the Cost of Informal Care

The “opportunity cost” associated with informal caregiving for activities of daily living is often estimated by using the average wage for a home health aide (36, 37), on the basis of the assumption that this wage represents the cost of purchasing similar caregiving activities in the market. We used this method to estimate the yearly cost of informal caregiving for respondents in each depressive symptom category by multiplying the 2000 median national wage for a home health aide ($8.23 per hour [50]) by the adjusted weekly hours of care and then multiplying by 52 (weeks per year). We then used the national prevalence estimates of depressive symptoms available from the AHEAD study to determine an estimate of the yearly national cost of informal caregiving associated with depressive symptoms. To provide a reasonable range of costs for informal caregiving, we performed a sensitivity analysis for annual national caregiving costs using the 10th percentile wage for a home health aide ($6.14 per hour) as a more conservative estimate of the opportunity cost of caregiver time and the 90th percentile wage ($11.93 per hour) as a more generous estimate (50).

Data Analysis

Descriptive data were analyzed with the Wald test and with the design-based F test (51), a modification of the Pearson chi-square test. The results of both statistical tests were adjusted to account for the complex sampling design of the AHEAD study.

Because a substantial proportion of the respondents received no informal care and because the distribution of hours among recipients of care was highly skewed, we constructed a two-part multivariate regression model using both logistic and ordinary least squares regression (52, 53). Details of the use of this analysis strategy with AHEAD caregiving data have been published previously (19, 47).

Analyses were weighted and adjusted for the complex sampling design (stratification, clustering, and nonresponse) of the AHEAD study (40). We tested for significant interaction effects among the independent variables and performed regression diagnostics to check for influential observations and heteroscedasticity in the residuals. All analyses were performed by using STATA Statistical Software: release 7.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, Tex.). The Health and Retirement Study/AHEAD study was approved by an institutional review board at the University of Michigan. The data used for this analysis contained no unique identifiers, so respondent anonymity was maintained.

Results

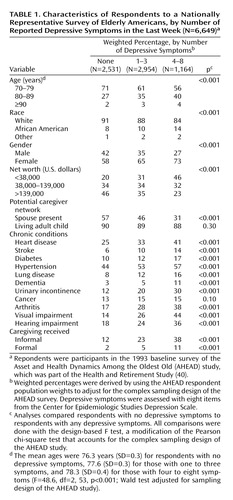

Descriptive information about the study sample is shown in Table 1. About 44% of the respondents reported one to three depressive symptoms in the last week, and 18% reported four to eight depressive symptoms. Compared to respondents without depressive symptoms, respondents with depressive symptoms were older; more likely to be African American, female, and have low net worth; and less likely to be living with a spouse (p<0.001, design-based F test). The presence of depressive symptoms was associated with significantly higher rates of all chronic medical conditions (p<0.001, design-based F test) except cancer (p=0.10, design-based F test). Depressive symptoms were also related to significantly higher rates of both informal and formal (paid) caregiving (p<0.001, design-based F test).

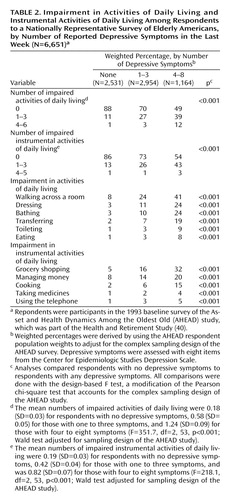

Table 2 shows rates of limitations in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living, by depressive symptom category. The number of depressive symptoms was strongly associated with the number of limitations. Only 12% of the respondents without depressive symptoms reported one or more limitations in activities of daily living (group mean of 0.18 limitations), while 51% of the respondents with four to eight depressive symptoms reported at least one limitation (group mean of 1.24 limitations) (p<0.001, design-based F test). A similar pattern was found for limitations in instrumental activities of daily living.

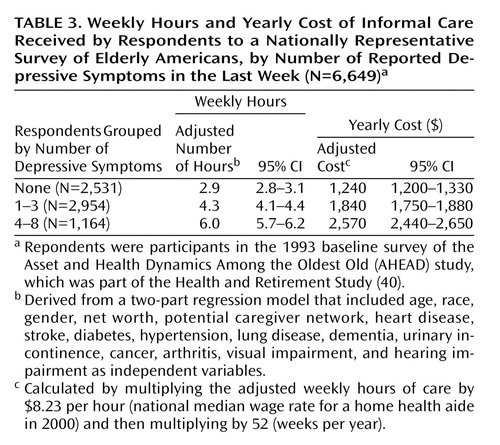

Results for informal caregiving hours and cost, after adjustment for all other covariates by using the two-part regression analysis, are shown in Table 3. Elderly individuals with no depressive symptoms received, on average, 2.9 hours per week of informal care, while those with one to three symptoms received 4.3 hours per week (or 1.4 additional hours of informal care, compared to those with no symptoms), and those with four to eight symptoms received 6.0 hours per week (or 3.1 additional hours of informal care, compared to those with no symptoms) (p<0.001, Wald test).

We tested the interaction of depressive symptoms and each of the other 11 chronic conditions for a significant effect on caregiving hours. None of these interaction terms achieved statistical significance in both parts of the two-part regression model. Inclusion of the interaction terms resulted in no significant effects on the estimate of caregiving hours for any of the depressive symptom categories.

In calculations that used the 2000 median home health aide wage ($8.23 per hour), the 1.4 additional weekly hours of informal care for respondents with one to three symptoms resulted in an additional yearly informal caregiving cost of about $600 per person ($8.23/hour × 1.4 hours/week × 52 weeks/year). For respondents with four to eight depressive symptoms, the additional yearly informal caregiving cost was about $1,330 per person.

Given the nationally representative sample of the AHEAD study, an estimate of the total informal caregiver time and cost associated with depressive symptoms among community-dwelling elderly individuals age 70 years or older in the United States could be calculated. Our results suggested that approximately 8.3 million older individuals had one to three depressive symptoms and that 3.1 million individuals had four to eight depressive symptoms. Multiplying these prevalence estimates by the additional cost per person yielded an additional yearly caregiving cost of about $5.0 billion for elderly persons with one to three depressive symptoms and $4.1 billion for elderly persons with four to eight depressive symptoms, for a total additional yearly caregiving cost in the United States of about $9.1 billion. By using the 10th percentile home health aide wage ($6.14 per hour) as an estimate of the cost of caregiver time, the total annual additional national cost would be about $6.8 billion; using the 90th percentile wage ($11.93 per hour) yielded an estimate of about $13.2 billion per year.

Discussion

This study of a nationally representative sample of older Americans confirmed that depressive symptoms are extremely common, are associated with significantly higher levels of disability, and are independently associated with higher levels of informal caregiving, even after adjustment for major coexisting chronic conditions. The additional hours of care found attributable to depressive symptoms in this study represent a significant time commitment for family members and, therefore, a significant societal economic cost.

The relationships among depressive symptoms, limitations in activities of daily living and in instrumental activities of daily living, and caregiving are likely complex. Longitudinal studies have demonstrated a bidirectional relationship between depressive symptoms and functional limitations, with depression at baseline associated with functional impairment at follow-up and functional limitations at baseline associated with depression at follow-up (4, 54–58). Depression and poor physical functioning may be mutually reinforcing, with each making the other more likely and each increasing the likelihood of poor outcomes (including the need for caregiving) among older individuals (4).

The association between depressive symptoms and functional limitations that we found in the AHEAD study was similar to that seen in earlier studies, with a continuous positive relationship between depressive symptoms and disability. Similarly, we found that informal care hours increased with increases in the number of depressive symptoms. In the AHEAD study, respondents with a score of 4 or more on the 8-item CES-D Scale, who had the highest probability of meeting the criteria for major depression, also had the highest levels of caregiving. It is interesting to note that the quantity of caregiving remained relatively constant for individuals with four to eight depressive symptoms (data not shown), suggesting that this cutoff point may indeed be useful in screening for major depression.

The fact that women were more likely than men to report depressive symptoms may put women at especially high risk of having unmet needs for informal care and social support. In a previous study, we showed that women with functional limitations received significantly fewer hours of informal care than men with similar levels of impairment (59). This difference was related to women’s greater likelihood of living alone, but even women who lived with a spouse received significantly less care than was provided to men with functional limitations. Older women were also much more likely than men to have low net worth, which perhaps made it more difficult to obtain paid home care or other necessary medical services. Given these realities, clinicians should be especially vigilant in determining whether older women with depressive symptoms have adequate levels of social support.

We note several potential limitations of this study. First, we used methods that likely led to conservative estimates of informal caregiving time and cost. The AHEAD data include only caregiving that was provided for help with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. The time required for caregivers to perform other activities that might be associated with depressive symptoms, such as transportation to physician appointments or providing expressive rather than instrumental support, were not included in the analysis. In addition, negative effects on paid employment, such as increased absenteeism or taking early retirement because of caregiving responsibilities, were not accounted for. Caregiving may cause negative health effects (60) or even increased mortality (61) among caregivers; the costs related to such possible outcomes were not included in this study. However, even with the conservative measures and the low-range opportunity cost estimate we used, the estimated national annual cost associated with caregiving for depressive symptoms still reached about $7 billion per year.

Second, as with all observational studies, the possibility existed that a variable omitted from our analysis (e.g., another comorbidity) that was correlated with both the presence of depressive symptoms and the presence of informal caregiving was the “true cause” of the higher rate of caregiving for respondents with depressive symptoms. However, we controlled for key sociodemographic measures, the extent of the potential caregiver network, and the presence of common comorbidities that have been shown to influence the level of informal care for older individuals. Since our estimate of the time and cost associated with informal caregiving for depressive symptoms was a conservative one, it is unlikely that we significantly overestimated the cost of caregiving for depression because we omitted a variable. Finally, it should also be noted that the wage of a home health aide might underestimate the societal economic cost of informal caregiving if the quality and effectiveness of paid home care were lower than that of the care provided by a committed spouse or child and since other costs associated with paid home care (e.g., administrative costs and employee benefits) were not included in the wage rate.

Clinicians and policy makers should be cognizant of the potential increased need for informal caregiving among older individuals with depressive symptoms. Clinicians should inquire about the adequacy of social support for their elderly patients with depressive symptoms and should also be alert to potential caregiver “burden” among the family members who provide care (and who are themselves likely to be elderly). When making decisions regarding the allocation of medical resources, policy makers should consider the substantial costs of informal caregiving for depressive symptoms, in addition to the clear effects of those symptoms on individuals’ independent functioning and quality of life. Including the costs of caregiving for older individuals with depressive symptoms will further improve the already favorable cost-effectiveness ratio of many broad-based collaborative interventions for the treatment of depression (62, 63).

|

|

|

An earlier version was presented at the national meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, Atlanta, May 2–4, 2002. Received Aug. 21, 2002; revision received May 29, 2003; accepted Aug. 1, 2003. From the Division of General Medicine, the Department of Psychiatry, the Institute for Social Research, the Patient Safety Enhancement Program, and the Society of General Internal Medicine Collaborative Center for Research and Education in the Care of Older Adults, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.; and the Department of Veterans Affairs Center for Practice Management and Outcomes Research, Ann Arbor, Mich. Address reprint requests to Dr. Langa, Division of General Medicine, University of Michigan Health System, 300 North Ingalls Building, Room 7E01, Box 0429, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-0429; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by Career Development Award K08 AG-19180 from the National Institute on Aging, a New Investigator Grant from the Alzheimer’s Association, and a Paul Beeson Physician Faculty Scholar Award to Dr. Langa; VA Health Services Research and Development Career Development Awards to Dr. Valenstein and Dr. Vijan; and grant U01 AG-09740 from the National Institute on Aging for the Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old (AHEAD) study, which was the source of the data used in this analysis.

1. Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LK, Tse CK: Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA 1990; 264:2524–2528Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL: Service utilization and social morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in the community. JAMA 1992; 267:1478–1483Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Bruce ML, Seeman TE, Merrill SS, Blazer DG: The impact of depressive symptomatology on physical disability: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Am J Public Health 1994; 84:1796–1799Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Penninx BW, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Deeg DJ, Wallace RB: Depressive symptoms and physical decline in community-dwelling older persons. JAMA 1998; 279:1720–1726Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Lyness JM, King DA, Cox C, Yoediono Z, Caine ED: The importance of subsyndromal depression in older primary care patients: prevalence and associated functional disability. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47:647–652Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Cronin-Stubbs D, de Leon CF, Beckett LA, Field TS, Glynn RJ, Evans DA: Six-year effect of depressive symptoms on the course of physical disability in community-living older adults. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:3074–3080Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Spertus JA, McDonell M, Woodman CL, Fihn SD: Association between depression and worse disease-specific functional status in outpatients with coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 2000; 140:105–110Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Ormel J, VonKorff M, Ustun TB, Pini S, Korten A, Oldehinkel T: Common mental disorders and disability across cultures: results from the WHO Collaborative Study on Psychological Problems in General Health Care. JAMA 1994; 272:1741–1748Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Linzer M, Hahn SR, Williams JBW, deGruy FV III, Brody D, Davies M: Health-related quality of life in primary care patients with mental disorders: results from the PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA 1995; 274:1511–1517Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Ormel J, Kempen GI, Deeg DJ, Brilman EI, van Sonderen E, Relyveld J: Functioning, well-being, and health perception in late middle-aged and older people: comparing the effects of depressive symptoms and chronic medical conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998; 46:39–48Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Simon GE, Katon W, Rutter C, VonKorff M, Lin E, Robinson P, Bush T, Walker EA, Ludman E, Russo J: Impact of improved depression treatment in primary care on daily functioning and disability. Psychol Med 1998; 28:693–701Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Penninx BW, Leveille S, Ferrucci L, van Eijk JT, Guralnik JM: Exploring the effect of depression on physical disability: longitudinal evidence from the established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. Am J Public Health 1999; 89:1346–1352Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Murray C, Lopez A: The Global Burden of Disease. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar

14. Williams J, Noel P, Cordes J, Ramirez G, Pignone M: Is this patient clinically depressed? JAMA 2002; 287:1160–1170Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Katon W, Robinson P, Von Korff M, Lin E, Bush T, Ludman E, Simon G, Walker E: A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:924–932Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Gallo JJ, Rabins PV, Anthony JC: Sadness in older persons: 13-year follow-up of a community sample in Baltimore, Maryland. Psychol Med 1999; 29:341–350Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Yaffe K, Blackwell T, Gore R, Sands L, Reus V, Browner WS: Depressive symptoms and cognitive decline in nondemented elderly women: a prospective study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:425–430Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Boaz RF, Hu J: Determining the amount of help used by disabled elderly persons at home: the role of coping resources. J Gerontol 1997; 52B:S317-S324Google Scholar

19. Langa KM, Chernew ME, Kabeto MU, Herzog AR, Ofstedal MB, Willis RJ, Wallace RB, Mucha L, Straus W, Fendrick AM: National estimates of the quantity and cost of informal caregiving for the elderly with dementia. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16:770–778Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Blazer D, Hughes DC, George LK: The epidemiology of depression in an elderly community population. Gerontologist 1987; 27:281–287Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Gallo JJ, Lebowitz BD: The epidemiology of common late-life mental disorders in the community: themes for the new century. Psychiatr Serv 1999; 50:1158–1166Link, Google Scholar

22. Beekman AT, Copeland JR, Prince MJ: Review of community prevalence of depression in later life. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174:307–311Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Gallo JJ, Anthony JC, Muthen BO: Age differences in the symptoms of depression: a latent trait analysis. J Gerontol 1994; 49:251–264Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Kirmayer LJ, Robbins JM, Dworkind M, Yaffe MJ: Somatization and the recognition of depression and anxiety in primary care. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:734–741Link, Google Scholar

25. Weich S, Lewis G, Donmall R, Mann A: Somatic presentation of psychiatric morbidity in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 1995; 45:143–147Medline, Google Scholar

26. Kerr LK, Kerr LD Jr: Screening tools for depression in primary care: the effects of culture, gender, and somatic symptoms on the detection of depression. West J Med 2001; 175:349–352Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Kim HF, Kunik ME, Molinari VA, Hillman SL, Lalani S, Orengo CA, Petersen NJ, Nahas Z, Goodnight-White S: Functional impairment in COPD patients: the impact of anxiety and depression. Psychosomatics 2000; 41:465–471Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Beckham JC, Burker EJ, Lytle BL, Feldman ME, Costakis MJ: Self-efficacy and adjustment in cancer patients: a preliminary report. Behav Med 1997; 23:138–142Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE: Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:3278–3285Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Daniels M, Berry S, Greenfield S, Ware J: The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 1989; 262:914–919Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Simon GE, VonKorff M, Barlow W: Health care costs of primary care patients with recognized depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:850–856Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Unutzer J, Patrick DL, Simon G, Grembowski D, Walker E, Rutter C, Katon W: Depressive symptoms and the cost of health services in HMO patients aged 65 years and older. JAMA 1997; 277:1618–1623Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM, Rosenheck RA: Depressive symptoms and health costs in older medical patients. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:477–479Abstract, Google Scholar

34. Ernst RL, Hay JW: Economic research on Alzheimer disease: a review of the literature. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1997; 11(suppl 6):135–145Google Scholar

35. Hayman JA, Langa KM, Kabeto MU, Katz SJ, DeMonner SM, Chernew ME, Slavin MB, Fendrick AM: Estimating the cost of informal caregiving for elderly patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19:3219–3225Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Arno PS, Levine C, Memmott MM: The economic value of informal caregiving. Health Aff (Millwood) 1999; 18:182–188Crossref, Google Scholar

37. Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC: Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

38. Valenstein M, Vijan S, Zeber JE, Boehm K, Buttar A: The cost-utility of screening for depression in primary care. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134:345–360Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Whooley M, Simon G: Managing depression in medical outpatients. N Engl J Med 2000; 343:1942–1950Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Soldo BJ, Hurd MD, Rodgers WL, Wallace RB: Asset and health dynamics among the oldest old: an overview of the AHEAD Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1997; 52(special number):1–20Google Scholar

41. Radloff LS: The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. J Applied Psychol Measurement 1977; 1:385–401Crossref, Google Scholar

42. Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, Allen NB: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol Aging 1997; 12:277–287Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Turvey CL, Wallace RB, Herzog R: A revised CES-D measure of depressive symptoms and a DSM-based measure of major depressive episodes in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr 1999; 11:139–148Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Steffick DE: Documentation of Affective Functioning Measures in the Health and Retirement Study, 2000. http://www.umich. edu/~hrswww/docs/userg/dr-005.pdfGoogle Scholar

45. Norgard TM, Rodgers WL: Patterns of in-home care among elderly black and white Americans. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1997; 52(special number):93–101Google Scholar

46. Wolf DA, Freedman V, Soldo BJ: The division of family labor: care for elderly parents. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1997; 52(special number):102–109Google Scholar

47. Langa KM, Chernew ME, Kabeto MU, Katz SJ: The explosion in paid home health care in the 1990s: who received the additional services? Med Care 2001; 39:147–157Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Brandt J, Spencer M, Folstein M: The telephone interview for cognitive status. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1988; 1:111–117Google Scholar

49. Gujarati DN: Basic Econometrics, 2nd ed. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1988Google Scholar

50. Bureau of Labor Statistics:2000 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates, 2001. http://www.bls.gov/oes/2000/oes311011.htmGoogle Scholar

51. Rao JNK, Scott AJ: On chi-squared tests for multiway contingency tables with cell proportions estimated from survey data. Annals of Statistics 1984; 12:46–60Crossref, Google Scholar

52. Duan N, Manning WG, Morris CN, Newhouse JP: A comparison of alternative models for the demand for medical care. J Business and Economic Statistics 1983; 1:115–126Google Scholar

53. Kemper P: The use of formal and informal home care by the disabled elderly. Health Serv Res 1992; 27:421–451Medline, Google Scholar

54. Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Smit JH, van Tilburg W: Predicting the course of depression in the older population: results from a community-based study in The Netherlands. J Affect Disord 1995; 34:41–49Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Armenian HK, Pratt LA, Gallo J, Eaton WW: Psychopathology as a predictor of disability: a population-based follow-up study in Baltimore, Maryland. Am J Epidemiol 1998; 148:269–275Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Prince MJ, Harwood RH, Thomas A, Mann AH: A prospective population-based cohort study of the effects of disablement and social milieu on the onset and maintenance of late-life depression: the Gospel Oak Project VII. Psychol Med 1998; 28:337–350Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Penninx BW, Deeg DJ, van Eijk JT, Beekman AT, Guralnik JM: Changes in depression and physical decline in older adults: a longitudinal perspective. J Affect Disord 2000; 61:1–12Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Geerlings SW, Schoevers RA, Smit JH, van Tilburg W: Emergence and persistence of late life depression: a 3-year follow-up of the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. J Affect Disord 2001; 65:131–138Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Katz SJ, Kabeto MU, Langa KM: Gender disparities in the receipt of home care for elderly people with disability in the United States. JAMA 2000; 284:3022–3027Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Schulz R, O’Brien AT, Fleissner K: Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: prevalence correlates, and causes. Gerontologist 1995; 35:771–791Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Schulz R, Beach SR: Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the caregiver health effects study. JAMA 1999; 262:2215–2219Crossref, Google Scholar

62. Schoenbaum M, Unutzer J, Sherbourne C, Duan N, Rubenstein LV, Miranda J, Meredith LS, Carney MF, Wells K: Cost-effectiveness of practice-initiated quality improvement for depression: results of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001; 286:1325–1330Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Simon GE, Katon WJ, VonKorff M, Unützer J, Lin EHB, Walker EA, Bush T, Rutter C, Ludman E: Cost-effectiveness of a collaborative care program for primary care patients with persistent depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1638–1644Link, Google Scholar