Psychiatric Morbidity Following Injury

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Accurate information regarding the psychopathological consequences of surviving traumatic injury is of great importance for effective health service design and planning. Regrettably, existing studies vary dramatically in reported prevalence rates of psychopathology within this population. The aim of this study was to identify the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity following severe injury by adopting a longitudinal design with close attention to optimizing the research methodology. METHOD: Consecutive admissions (N=363) to a level 1 trauma service, excluding those with moderate or severe traumatic brain injury, were assessed at three time periods: just before discharge and 3 and 12 months after their injury. Structured clinical interviews were used to assess anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and substance use disorders. RESULTS: Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder were the most frequent diagnoses at both 3 and 12 months, with 10% of participants meeting diagnostic criteria for each disorder at 12 months. Over 20% of the group met criteria for at least one psychiatric diagnosis 12 months after their injury. Comorbidity was common, with the most frequent being PTSD with major depressive disorder. CONCLUSIONS: Psychopathology following injury is a frequent and persistent occurrence. Despite the adoption of a rigorous and potentially conservative methodology, one-fifth of participants met criteria for one or more psychiatric diagnoses 12 months after their injury. These findings have major implications for injury health care providers.

Physical injuries in civilian populations are frequent events. One-third of all emergency department admissions in the United States are due to injury (1). Every year in Australia, 10.5% of the population suffers an injury requiring admission to an emergency department (2). Furthermore, advances in injury care systems have seen an increase in the number of seriously injured people surviving their injuries (3). Given that physical injury has long been identified as a traumatic stressor (4), understanding the psychological impact of surviving an injury is important.

Although increasing interest has been devoted to the psychological consequences of surviving a physical injury, two things are apparent when reviewing the literature. First, most research has focused on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), with only a few studies investigating major depressive episode, and even fewer evaluating the incidence of other disorders. Second, prevalence rates vary dramatically across studies. While cross-cultural and population differences undoubtedly explain some of this variance, methodological problems inherent in research with this population may also contribute to the disparate findings (5). Thus, methodologically rigorous studies of psychiatric morbidity following serious physical injuries are urgently required.

This disparity in prevalence rates of injury-related psychiatric morbidity is apparent from a brief review of the literature. The prevalence of PTSD between 2 and 6 months after a trauma, for example, has been variously quoted as 17.5% (6), 23.1% (7), and 42% (8). PTSD prevalence rates at 12 months show even greater variation, with studies from various countries reporting 1.9% (9), 16.5% (7), and 33% (10). With acute stress disorder being a relatively new diagnosis, few studies to date have reported acute stress disorder prevalence rates. However, the Bryant and Harvey research group have reported several studies of injury survivors that identify acute stress disorder rates of 13% in consecutive hospital admissions (11), 14% in participants with minor traumatic brain injury (12), and 16% in motor vehicle accident survivors with nontraumatic brain injury (13). Mellman et al. (14) found a similar acute stress disorder prevalence of 16% in their study of hospitalized injury survivors. While the prevalence of depression was reported in only a few studies, rates for this condition also vary. Rates of depression in the early period after a trauma have been reported as 8% (14), 19% (6), and 60% (15), while 6–12 month prevalence data for depression include rates of 8.5% (9) and 31% (15). The reported prevalence of other anxiety disorders includes rates for travel anxiety (28%) (10) as well as panic disorder (6%), generalized anxiety disorder (4%), and simple phobia (4%) (14).

Few studies have examined psychiatric comorbidity in an injured population. It is well established that PTSD, particularly in more chronic forms, rarely occurs alone and is routinely associated with other psychiatric conditions. In the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being (16), for example, 85% of men and 80% of women with PTSD met criteria for another psychiatric diagnosis. Major depressive episode, generalized anxiety disorder, and substance abuse were the most common comorbid disorders with PTSD in male subjects, while major depressive episode and generalized anxiety disorder were most common in women (16). Shalev et al. (6) found that of the 18% of injury survivors with PTSD, 43% had a comorbid major depressive episode. Mayou and colleagues (17), in a study of motor vehicle accident survivors, found that 74% of those with PTSD also reported comorbid anxiety disorders.

Clearly, the discrepancies in psychiatric morbidity rates for this population are a cause for concern. Part of the explanation may lie in methodological limitations and inconsistencies across the various studies. First, many studies fail to use standardized and valid measures of psychiatric morbidity. For the purpose of identifying prevalence rates, stringent assessment methods should be utilized, with an emphasis on established structured clinical interviews. Second, characteristics of this population render it particularly difficult to assess. Specifically, the manner in which researchers address issues such as head injury and analgesia use, and the extent to which attempts are made to differentiate between symptoms of organic and psychogenic origin, may confound findings and lead to disparate prevalence rates. Third, much research in this area fails to obtain a representative sample. For example, the percentage of hospitalized physically injured male survivors (relative to female) in North America is approximately 65%–75% (18). However, many studies utilizing a treatment-seeking or other self-selected population have a higher female-to-male ratio. Thus, the psychopathology prevalence rates identified by these studies have limited generalizability to the broader injury survivor population. Specifically, given that women are more likely than men to develop psychopathology following trauma (19), a higher female-to-male ratio may overestimate levels of psychopathology. Consecutive admissions or random allocation should be utilized to obtain a representative sample.

The aim of the current study was to comprehensively assess in subjects consecutively admitted to a trauma service the nature and prevalence of psychiatric morbidity over the first 12 months following a severe injury.

Method

Participants

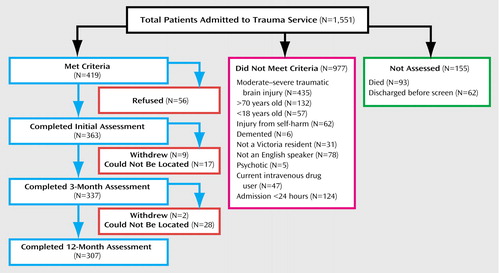

Subjects consecutively admitted (including those admitted on a weekend) to a level 1 trauma service in Victoria, Australia, were eligible for the study. Individuals were included in the current study if they 1) experienced a physical injury that required an admission of at least 24 hours to the Trauma Service; 2) experienced either no brain injury or mild traumatic brain injury (as defined by the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine [20]); 3) were between 18 and 70 years of age; and 4) had a reasonable comprehension of English. Participants were excluded if the injury was a result of deliberate self-harm, if they were currently abusing intravenous substances, or if they had a current psychotic disorder. Figure 1 presents a flow chart of those included and excluded from the study.

Participants were recruited over an 18-month period. During this time, 419 individuals met inclusion criteria and were approached to participate in the study. After a complete description of the study, written consent was obtained from 363 participants (87%). Interview and self-report data were collected just before discharge. Follow-up telephone assessments were conducted 3 and 12 months after the trauma. A total of 337 participants (93% of those who commenced the study) completed the 3-month assessment and 307 participants (85% of those who commenced the study) completed the 12-month assessment.

Individuals who refused to participate in the current study did not differ from those who participated in terms of gender (χ2=3.80, df=1, n.s.), age (t=1.00, df=410, n.s.), days in the hospital (t=1.79, df=409, n.s.), injury severity score (t=0.05, df=442, n.s.), the presence of a head injury (χ2=0.00, df=1, n.s.), or discharge destination (home or rehabilitation service) (χ2=1.20, df=1, n.s.).

Subjects who did not complete the 3-month diagnostic interviews did not differ from those who did in terms of gender (χ2=0.54, df=1, n.s.), mild traumatic brain injury (χ2=0.02, df=1, n.s.), discharge destination (χ2=0.01, df=1, n.s.), number of days in the hospital (t=1.34, df=361, n.s.), or injury severity (t=0.32, df=358, n.s.). Noncompleters did differ from completers in terms of age (t=2.14, df=361, p<0.05), with noncompleters more likely to be younger. On psychological variables, noncompleters did not differ significantly in terms of depression (t=0.61, df=24.58, n.s.) or anxiety levels (t=1.79, df=354, n.s.) just before discharge.

Individuals who failed to complete the 12-month assessment did not differ from 12-month completers in terms of gender (χ2=0.14, df=1, n.s.), mild traumatic brain injury (χ2=0.85, df=1, n.s.), discharge destination (χ2=0.48, df=1, n.s.), or injury severity (t=1.89, df=358, n.s.). However, they did differ in terms of age (t=3.92, df=87.08, p<0.001) and number of days in the hospital (t=1.98, df=360, p<0.05), with noncompleters being more likely to be younger and having spent fewer days in the hospital. Noncompleters also reported higher levels of both anxiety (t=3.14, df=354, p<0.05) and depression (t=3.29, df=354, p<0.001) just before discharge, suggesting that the reported 12-month prevalence rates may be a slight underestimate.

The majority of participants were male (N=273 [75%]), and the average age was 36 years (SD=13.43). The average injury severity score (21) was 12.80 (SD=9.73); 33% (N=121) of participants experienced a severe injury (injury severity score ≥15), 31% (N=113) had a moderate injury (injury severity score=10–14), and 36% (N=129) experienced a mild injury (injury severity score=0–9). Participants spent an average of 10.13 days (SD=9.64) in the Trauma Centre, with 31% (N=113) requiring an intensive care unit admission. Motor vehicle accidents were the principle mechanism of injury (74% [N=270]), while 9% (N=33) of injuries occurred at work, and 13% (N=47) were due to other accidents. Thirteen people (4%) were assaulted. A total of 202 participants (56%) met criteria for a mild traumatic brain injury (20): loss of consciousness of 30 minutes or less, a Glasgow Coma Scale (22) score of 13–15 after 30 minutes, or posttraumatic amnesia not greater than 24 hours. Approximately half the participants (53% [N=192]) were discharged home while the remainder were discharged to a rehabilitation facility.

The study sample resembled the characteristics of all trauma service admissions for the same time period with regard to gender (p=0.47, Fisher’s exact test) and mechanism of injury (p=0.43, Fisher’s exact test). The current study’s patient group, relative to the total population, was younger (mean=36 years [SD=13.43] versus 41 years [SD=21.06]; t=4.40, df=1912, p<0.001) and had a lower injury severity score (mean=12.80 [SD=9.73] versus 17.11 [SD=13.18]; t=5.87, df=1912, p<0.001). This is not surprising given that we excluded those over 70 years of age at admission, as well as all admissions with moderate to severe brain injury and, of course, those who were deceased.

Measures

The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-IV (23) was used to assess PTSD after 3 and 12 months. This structured clinical interview is one of the most widely used tools for diagnosing PTSD and measuring PTSD severity and has demonstrated excellent reliability and validity (24). The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale, with its additional dissociation questions, was used also to assess acute stress disorder. Following common practice, both acute stress disorder and PTSD were scored using the “1-2 rule” (i.e., diagnostic criteria were met for each symptom if frequency ≥1 and intensity ≥2) (25). Since the diagnosis of PTSD is, by definition, tied to a specific event, it was assessed in this study with specific reference to the injury-producing event.

After 3 and 12 months, anxiety disorders, affective disorders, and substance use disorders were assessed by using the relevant modules of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (26). The SCID is one of the most widely used and thoroughly researched psychiatric clinical interviews (27). At the 3-month assessment, participants were asked about the duration of any conditions that met diagnostic criteria; those that had been present for more than 3 months were deemed to have been present before the traumatic event.

Self-report measures of anxiety and depression were also obtained with the Beck Anxiety Inventory (28) and the Beck Depression Inventory (29).

Two trained mental health clinicians conducted all structured clinical interviews. One-third of all clinical interviews were audiotaped, and one-third of those (approximately 10% of all assessments) were randomly selected and rated for interrater reliability. A high level of interrater agreement on diagnosis was obtained (kappa=0.95).

Procedure

Since blood loss and pain can produce symptoms that could be misinterpreted as psychogenic in nature, initial assessment was conducted just before discharge from the acute hospital. At this time, patients were hemodynamically stable and were relatively pain free. Since narcotic analgesia has side effects that can mimic dissociative symptoms (e.g., CNS disturbances), assessments were conducted at least 24 hours after intravenous narcotic cessation (mean=2.53 days, SD=2.37). Fifteen participants (4%) were receiving oral narcotic analgesia at the time of the assessment. There were no significant differences in current dissociative symptom levels between those receiving and not receiving oral narcotic analgesia (t=1.07, df=361, n.s.). The mean time of assessment was 7.74 days (SD=6.52) after admission and 2.45 days (SD=4.92) before discharge.

A diagnosis of acute stress disorder per DSM-IV requires three of five peritraumatic dissociative symptoms (“while experiencing or after experiencing” the trauma) to be present. However, the measurement of peritraumatic dissociation is difficult with an injured population. Many injured individuals experience mild traumatic brain injury, are administered narcotic analgesia at the scene of the trauma, or are intoxicated at the time of the incident, all of which may produce dissociative-like symptoms (30). In the current study, most participants were administered narcotic analgesia at the scene of the trauma and over 50% experienced a mild traumatic brain injury, making retrospective reports of peritraumatic dissociative symptoms unreliable. To avoid this potential confound, at the initial assessment participants were asked about current dissociative symptoms by modifying the dissociative questions of the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. The dissociative questions were modified by asking “How often has that happened in the past ? days,” with the interviewer inserting the number of days since intravenous narcotic analgesia had ceased.

Given the potential overlap between organic and psychogenic symptoms, care was taken to ensure that symptoms were psychogenic in origin. Both clinical assessors were sensitive to the consequences of physical injury and mild traumatic brain injury and trained to ask appropriate probes to detect differential diagnoses (i.e., whether a symptom was best accounted for by a nonpsychiatric explanation). Symptoms that were better accounted for by, for example, pain, hospital environment, or the injuries themselves were not scored as psychiatric symptoms.

In the follow-up assessments, care was taken to differentiate between various conditions such that a disorder was diagnosed only if it was not better explained by another diagnosis. For example, the reexperiencing phenomena that are characteristic of PTSD (intrusive memories of the traumatic event) were differentiated from the general ruminative worry (often about the consequences of the injuries) that is more characteristic of depression or generalized anxiety disorder. Avoidance was accepted as a PTSD symptom if it was specifically associated with attempts to avoid reminders of the trauma (i.e., functionally aimed at reducing the likelihood of activating unpleasant traumatic memories). If avoidance was engaged to prevent the occurrence of a feared outcome, and thereby reduce anxiety, it was identified with another anxiety disorder (specific phobia or panic disorder). If the avoidance was more associated with a lack of motivation and energy, it was seen as depressive phenomenology. If the avoidance was related to the current environment or physical incapacity, it was not deemed to be a psychiatric symptom. Thus, prevalence estimates of psychiatric morbidity in this study are considered to be conservative.

Results

Initial Prevalence Rates

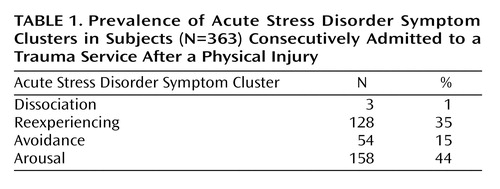

The incidence of acute stress disorder at the first assessment (i.e., around one week after the trauma) was 1% (N=3). The incidence of PTSD (excluding the duration criteria of 4 weeks) was 3% (N=9), which is consistent with the findings of Schnyder et al. (9). Given the low rates of acute stress disorder, analyses were conducted to identify the prevalence of each symptom cluster. Table 1 indicates the frequencies for each acute stress disorder symptom cluster.

This table demonstrates that while many participants met acute stress disorder criteria for reexperiencing, arousal, and avoidance, very few met criteria for dissociation (three or more dissociative symptoms). In fact, the three participants who met the dissociation criteria were also those who met diagnostic criteria for acute stress disorder.

It is worth noting that 17% (N=60) of participants reported moderate to severe levels of anxiety (score ≥19 on the Beck Anxiety Inventory), and 15% (N=53) reported moderate to severe levels of depression (score ≥19 on the Beck Depression Inventory) at this point. This suggests that despite few participants meeting criteria for acute stress disorder/PTSD, a significant proportion were experiencing high levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms just before discharge.

Prevalence Rates After 3 and 12 Months

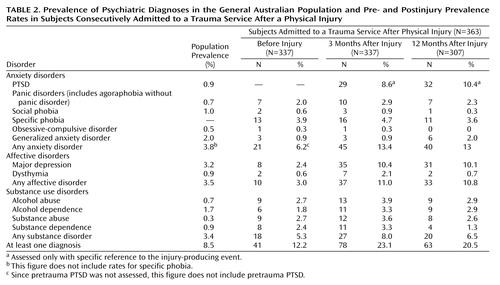

Table 2 shows the rates of key psychiatric conditions present before the traumatic event as well as 3 and 12 months after the injury. As a comparison, current prevalence rates for the general Australian population (31) are shown also.

Comorbidity

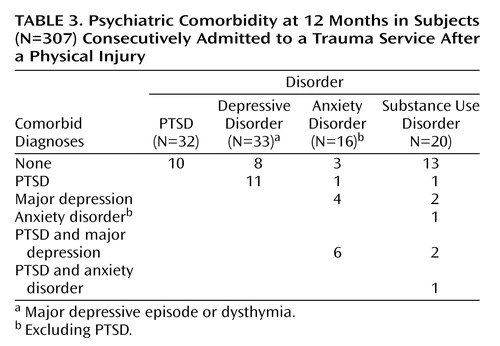

Table 3 displays the number of participants who met diagnostic criteria for a mental health condition after their injury and the level of comorbidity for each diagnosis. In examining comorbidity, the anxiety disorders (excluding PTSD) were grouped together under the heading of anxiety disorder (i.e., panic disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder). The substance use disorders were grouped together to form the substance use disorders category (i.e., substance abuse, substance dependence, alcohol use, alcohol dependence). Depressive disorders (dysthymia and major depression) were grouped together. In line with previous research, the most common comorbid condition with PTSD was a depressive disorder.

Table 2 shows that 20.5% (N=63) of all participants who completed the 12-month assessment met diagnostic criteria for at least one psychiatric disorder. Of those with at least one diagnosis, 46% (N=29) had a comorbid diagnosis. Specifically, 54% of participants with diagnosable psychopathology (N=34) had a single diagnosis, 32% (N=20) met criteria for two diagnoses, and 14% (N=9) met criteria for three diagnoses. Only 30% (N=10) of individuals with PTSD had PTSD as their only diagnosis, 24% (N=8) of those with a depressive disorder had depression as their only diagnosis, and 19% (N=3) of those with an anxiety disorder had this as their only diagnosis. It is interesting that many of those with a substance use disorder (65% [N=13]) had substance use disorder as their only diagnosis. Over half the participants with PTSD had comorbid depression (59% [N=19]).

Discussion

The percentage of participants meeting criteria for acute stress disorder according to DSM-IV was considerably lower than the rates of 16% (14) and 13% (11) found in other prospective studies utilizing similar populations. It is possible that the rigorous methodology in the current study may have contributed to this low rate, particularly given that many individuals failed to meet the three dissociative symptoms required for a diagnosis of acute stress disorder. The issue of measuring peritraumatic dissociation in the injured population is contentious. Not only is traumatic brain injury and paramedic-administered narcotic analgesia a potential confound, but much research shows that injured populations have high prevalence of alcohol and other substance intoxication at the time of the injury (32, 33). Our decision to measure current dissociation rather than peritraumatic dissociation was an attempt to avoid the above confounds. While there is increasing evidence that current dissociation is a better predictor of PTSD than peritraumatic dissociation (e.g., reference 34), in the current study it contributed to the low numbers of individuals reaching acute stress disorder diagnostic criteria. To date, studies that have measured peritraumatic dissociation in the injured population have not explained how they addressed these issues.

The rate of acute PTSD (excluding the duration criteria), which does not require dissociative symptoms, was also very low (relative to 3- and 12-month PTSD rates). However, the current rate is comparable with that found by Schnyder et al. (9) using a similar sample. It may be that the timing of the assessment contributed to these low diagnosis rates. Differences in symptom severity between those who develop chronic PTSD and those who do not have been shown to increase over the first 3 months (35–37). It may be that, within the acute hospital setting, psychological symptoms remain underdeveloped. For example, the patient may see the hospital as a “safe” environment because medical assistance is immediately available, social support is generally increased, and responsibilities are delayed. Furthermore, this is a time where the focus of recovery is on the physical self, which may impede or delay focus on the psychological self. Finally, some psychological symptoms may not yet have developed because of a lack of exposure to trauma triggers. For example, avoidant strategies may not have been engaged due to the lack of opportunities to confront anxiety-provoking situations (e.g., if injuries occurred as a consequence of a motor vehicle accident, a patient in the hospital has had no opportunity to travel in a vehicle).

The low rates of acute stress disorder just before discharge may also reflect problems with the acute stress disorder diagnostic criteria. Acute stress disorder was introduced into the DSM-IV taxonomy in 1994 with the aim of identifying individuals at high risk for developing PTSD (38, 39). Since that time, the diagnostic criteria have been criticized, particularly with regard to the dissociative criteria (40, 41). The current results suggest that the acute stress disorder diagnosis may not be an effective identifier of high risk in the acute trauma setting. That is, many individuals in our study who did not meet criteria for acute stress disorder went on to develop PTSD. Given that initial depression and anxiety symptoms have been associated with later PTSD development (e.g., references 6, 42, 43), the high rates of these problems in the current study (as measured by the Beck Depression Inventory and the Beck Anxiety Inventory) may be a better guide to subsequent PTSD prevalence.

The finding that over 20% of injury survivors met diagnostic criteria for at least one psychiatric diagnosis at 12 months is disturbing given the frequency with which injury occurs. PTSD and depressive disorders were the most frequent diagnoses, accounting for 53% of all diagnoses. Approximately half of those who were diagnosed with one psychiatric condition also met criteria for another diagnosis, with PTSD being most frequently comorbid with depression. These findings are consistent with the epidemiological literature that shows a close relationship between PTSD and depression. The occurrence of PTSD and depression as single diagnoses (i.e., not comorbid with another disorder) was relatively unusual, occurring in only approximately one-third of the cases. Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of investigating comorbid diagnoses when assessing individuals after a trauma. The high prevalence of comorbid disorders following injury may have important implications for expected outcomes of treatment (44).

Given that 75% of participants received their injuries through motor vehicle accidents, it is interesting to note the differences in our findings relative to those of Mayou et al. (17), who examined prevalence and comorbidity in motor vehicle accident survivors. Unlike their findings, the current study did not identify an increase in simple phobia (referred to as travel anxiety by Mayou et al.). One explanation for this is that in the current study, structured clinical interviews were used to diagnose psychopathology in contrast to the self-report questionnaires used by Mayou et al. Second, in the current study, if avoidance was better accounted for by a PTSD diagnosis, it was not then used for a phobic diagnosis. While several participants were avoidant of motor vehicle transportation after their injury, clinical inquiry identified this avoidance as an attempt to avoid reminders of the accident rather than a distinct phobic reaction. As these individuals were also experiencing intrusive and hyperarousal phenomena, these symptoms were seen as being better accounted for under a PTSD diagnosis.

Given the conservative methodology used in this study, it could be argued that psychopathology was underdiagnosed. While this may be the case, the relative dearth of studies examining psychopathology following injury and the difficulty in assessing injured populations necessitate establishment of a reliable baseline that accounts for potential confounds. Such studies are then useful standards on which to compare less methodologically rigorous studies (such as those utilizing self-report scales). This research represents one of the few attempts to rigorously evaluate the presence of a broad range of mental health conditions in a severely injured population.

While the current results implicate methodological differences between studies as a partial explanation for the variable prevalence rates, it is important to note that methodology is unlikely to fully explain the differential findings across studies. Although it is beyond the scope of this study to address all potential contributors to varying prevalence rates, cross-national differences warrant some discussion. Psychiatric research in other populations shows that cross-national differences can contribute significantly to prevalence differences (e.g., reference 45). With relevance to the current study is the finding that PTSD prevalence in the general community is known to vary across countries. The 12-month PTSD prevalence rate in the United States, for example, has been reported at 3.9% (46) compared to 1.3% in Australia (16). Cross-national differences in the trauma center population may have particular relevance in the current study. In our sample, less than 5% sustained their injuries through interpersonal violence as compared with studies conducted in the United States, where rates of intentional injury are much higher (e.g., 16% [8], 20% [14], and 35% [47]). Since interpersonal violence is associated with a higher risk of PTSD than, for example, accidental injury (16, 48), these population differences may go some way to explaining the variance in prevalence rates across studies.

In interpreting the current data, it is important to note that the prevalence of posttrauma substance use disorders may be an underestimation, since 47 individuals were excluded on the basis of current intravenous substance use at the time of admission. It is reasonable to speculate that a significant proportion of these individuals would have met diagnostic criteria for a substance use disorder in the 12 months following admission. Furthermore, dropouts before the 12-month assessment were more likely to have had higher depressive and anxiety symptoms at initial assessment. As depressive and anxiety characteristics are associated with vulnerability to psychopathology (e.g., references 6, 17), it is likely that these dropouts served to reduce subsequent prevalence rates. Thus, our psychopathology prevalence rates should be regarded as a minimum level of that which may be expected following severe physical injury. It is important to note that these data do not claim to be representative of all trauma center injury survivors, particularly with regard to the extent of head injury.

Despite these limitations, the high levels of psychopathology evident in the year following the trauma indicate that psychiatric disorders frequently and persistently occur following a physical injury. Health care systems targeted at traumatically injured populations have a responsibility to adopt an evidence-based approach both to early identification of high-risk individuals and to early psychiatric intervention.

|

|

|

Presented in part at the 17th annual meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, New Orleans, Dec. 4–8, 2001. Received Aug. 6, 2002; revision received March 19, 2003; accepted June 17, 2003. From the Departments of Psychology and Psychiatry, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia; the Australian Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health; and the Department of Trauma Services, The Alfred Hospital, Prahran, Australia. Address reprint requests to Dr. O’Donnell, Australian Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health, P.O. Box 5444, Heidelberg, Victoria 3081, Australia; [email protected] (e-mail). This study was supported by the Victorian Trauma Foundation, grant number V-11. The authors thank the patients and staff at the Alfred Hospital Trauma Service for their participation and assistance.

Figure 1. Study Progression of Subjects Consecutively Admitted to a Trauma Service After a Physical Injury

1. McCaig LF, Burt CW: National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey:1999 Emergency Department Summary. Advance Data From Vital and Health Statistics 320. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, 2001Google Scholar

2. Watson WL, Ozanne-Smith J: Injury surveillance in Victoria, Australia: developing comprehensive injury incidence estimates. Accid Anal Prev 2000; 32:277–286Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Shackford SR, Mackersie RC, Hoyt DB, Baxt WG, Eastman AB, Hammill FN, Knotts FB, Virgilio RW: Impact of a trauma system on outcome of severely injured patients. Arch Surgery 1987; 122:523–527Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Green BL: Defining trauma: terminology and generic stressor dimensions. J Appl Social Psychol 1990; 20(20, part 2):1632–1642Google Scholar

5. O’Donnell ML, Creamer M, Bryant RA, Schnyder U, Shalev A: Posttraumatic disorders following injury: an empirical and methodological review. Clin Psychol Rev 2003; 23:587–603Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Shalev AY, Freedman S, Peri T, Brandes D, Sahar T, Orr SP, Pitman RK: Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following trauma. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:630–637Link, Google Scholar

7. Ehlers A, Mayou RA, Bryant B: Psychological predictors of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder after motor vehicle accidents. J Abnorm Psychol 1998; 107:508–519Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Michaels AJ, Michaels CE, Moon CH, Smith JS, Zimmerman MA, Taheri PA, Peterson C: Posttraumatic stress disorder after injury: impact on general health outcome and early risk assessment. J Trauma 1999; 47:460–466Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Schnyder U, Moergeli H, Klaghofer R, Buddeberg C: Incidence and prediction of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in severely injured accident victims. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:594–599Link, Google Scholar

10. Mayou R, Bryant B: Outcome in consecutive emergency department attenders following a road traffic accident. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 179:528–534Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Harvey AG, Bryant RA: Acute stress disorder across trauma populations. J Nerv Ment Dis 1999; 187:443–446Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Bryant RA, Harvey AG: Relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder following mild traumatic brain injury. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:625–629Link, Google Scholar

13. Harvey AG, Bryant RA: Predictors of acute stress following motor vehicle accidents. J Trauma Stress 1999; 12:519–525Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Mellman TA, David D, Bustamante V, Fins AI, Esposito K: Predictors of post-traumatic stress disorder following severe injury. Depress Anxiety 2001; 14:226–231Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 . Holbrook TL, Anderson JP, Sieber WJ, Browner D, Hoyt DB: Outcome after major trauma: discharge and 6-month follow-up results from the trauma recovery project. J Trauma 1998; 45:315–323Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 . Creamer M, Burgess P, McFarlane AC: Post-traumatic stress disorder: findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being. Psychol Med 2001; 31:1237–1247Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Mayou R, Bryant B, Ehlers A: Prediction of psychological outcomes one year after a motor vehicle accident. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1231–1238Link, Google Scholar

18. National Center for Health Statistics: Health Statistics, United States, 1996–97. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, 1997Google Scholar

19. Breslau N, Davis G-C, Andreski P, Peterson E-L, Schultz L-R: Sex differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:1044–1048Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine: Definition of mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 1993; 8:86–87Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Baker SP, O’Neil B, Haddon W Jr, Long WB: The Injury Severity Score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma 1974; 14:187–196Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Teasdale G, Jennett B: Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness: a practical scale. Lancet 1974; 2:81–84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Charney DS, Keane TM: Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-IV. Boston, National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, 1998, pp 1–19Google Scholar

24. Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JRT: Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: a review of the first ten years of research. Depress Anxiety 2001; 13:132–156Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Weathers FW, Ruscio AM, Keane TM: Psychometric properties of nine scoring rules for the Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale. Psychol Assess 1999; 11:124–133Crossref, Google Scholar

26. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1996Google Scholar

27. Wilson JP, Keane TM (eds): Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD: A Practitioner’s Handbook. New York, Guilford, 1996Google Scholar

28. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA: An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988; 56:893–897Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK: Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd ed, Manual. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1996Google Scholar

30. Bryant RA: Posttraumatic stress disorder and mild brain injury: controversies, causes and consequences. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2001; 23:718–728Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Andrews G, Henderson S, Hall W: Prevalence, comorbidity, disability and service utilization: overview of the Australian National Mental Health Survey. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 178:145–153Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Gurney JG, Seguin D, Fligner CL, Ries R, Raisys VA, Copass M, Thal E: The magnitude of acute and chronic alcohol-abuse in trauma patients. Arch Surgery 1993; 128:907–913Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Soderstrom CA, Dischinger PC, Kerns TJ, Kufera JA, Mitchell KA, Scalea TM: Epidemic increases in cocaine and opiate use by trauma center patients: documentation with a large clinical toxicology database. J Trauma 2001; 51:557–564Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Murray J, Ehlers A, Mayou RA: Dissociation and post-traumatic stress disorder: two prospective studies of road traffic accident survivors. Br J Psychiatry 2002; 180:363–368Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Koren D, Arnon I, Klein E: Acute stress response and posttraumatic stress disorder in traffic accident victims: a one-year prospective, follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:367–373Abstract, Google Scholar

36. Shalev AY, Peri T, Canetti L, Schreiber S: Predictors of PTSD in injured trauma survivors: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:219–225Link, Google Scholar

37. Shalev AY, Sahar T, Freedman S, Peri T, Glick N, Brandes D, Orr SP, Pitman RK: A prospective study of heart rate response following trauma and the subsequent development of posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:553–559Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Koopman C, Classen C, Cardena E, Spiegel D: When disaster strikes, acute stress disorder may follow. J Trauma Stress 1995; 8:29–46Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Rothbaum BO, Foa EB: Subtypes of posttraumatic stress disorder and duration of symptoms, in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: DSM-IV and Beyond. Edited by Davidson JTR, Foa EB. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993, pp 23–35Google Scholar

40. Bryant RA, Harvey AG: Acute stress disorder—a critical review of diagnostic issues. Clin Psychol Rev 1997; 17:757–773Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Marshall RD, Spitzer R, Liebowitz MR: Review and critique of the new DSM-IV diagnosis of acute stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1677–1685Abstract, Google Scholar

42. Freedman SA, Brandes D, Peri T, Shalev A: Predictors of chronic post-traumatic stress disorder: a prospective study. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174:353–359Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Harvey AG, Bryant RA: The relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: a 2-year prospective evaluation. J Consult Clin Psychol 1999; 67:985–988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Shalev AY: Measuring outcome in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61(suppl 5):33–42Google Scholar

45. Simon GE, Goldberg DP, Von Korff M, Ustun TB: Understanding cross-national differences in depression prevalence. Psychol Med 2002; 32:585–594Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Kessler RC, Zhao S, Katz SJ, Kouzis AC, Frank RG, Edlund M, Leaf P: Past-year use of outpatient services for psychiatric problems in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:115–123Link, Google Scholar

47. Zatzick DF, Kang S-M, Müller H-G, Russo JE, Rivara FP, Katon W, Jurkovich GJ, Roy-Byrne P: Predicting posttraumatic distress in hospitalized trauma survivors with acute injuries. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:941–946Link, Google Scholar

48. Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:626–632Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar