Symptomatic and Functional Recovery From a First Episode of Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disorder

Abstract

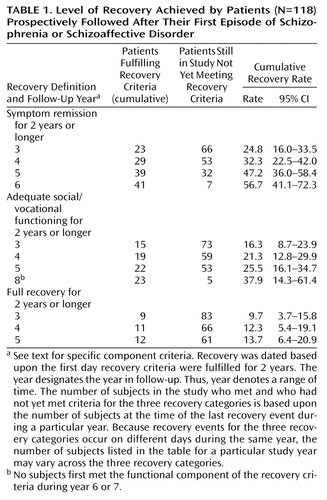

OBJECTIVE: Follow-up studies have found that a substantial number of patients with schizophrenia achieve full recovery (i.e., sustained improvement in both symptoms and social/vocational functioning) when examined decades after an index admission. This study addressed recovery during the crucial early course of the illness. METHOD: Subjects in their first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (N=118) were assessed at baseline and then treated according to a medication algorithm. Full recovery required concurrent remission of positive and negative symptoms and adequate social/vocational functioning (fulfillment of age-appropriate role expectations, performance of daily living tasks without supervision, and engagement in social interactions). RESULTS: After 5 years, 47.2% (95% CI=36.0%–58.4%) of the subjects achieved symptom remission, and 25.5% (95% CI=16.1%–34.7%) had adequate social functioning for 2 years or more. Only 13.7% (95% CI=6.4%–20.9%) of subjects met full recovery criteria for 2 years or longer. Better cognitive functioning at stabilization was associated with full recovery, adequate social/vocational functioning, and symptom remission. Shorter duration of psychosis before study entry predicted both full recovery and symptom remission. More cerebral asymmetry was associated with full recovery and adequate social/vocational functioning; a schizoaffective diagnosis predicted symptom remission. CONCLUSIONS: Although some patients with first-episode schizophrenia can achieve sustained symptomatic and functional recovery, the overall rate of recovery during the early years of the illness is low.

Follow-up studies (1, 2) examining outcome decades after an index episode have been the primary source of data about full recovery (i.e., sustained improvement in both symptoms and social/vocational functioning) among patients with schizophrenia. These studies provided the important information that about half of patients eventually recover or have only mild impairment. However, these investigations were limited by their reliance on retrospective information. In addition, because the initial evaluations were done decades ago, data were not available for many biological and clinical measures of current interest. There have been no follow-up studies of recovery during the crucial early phase of the illness.

Our study addressed the following questions. How frequently do patients recover during the early course of schizophrenia? What are the predictors of early recovery? Do predictors of full recovery differ from predictors of symptom remission and predictors of adequate social/vocational functioning? In order to study recovery prospectively, subjects must be assessed frequently in multiple domains over a long period of time. We were able to address our questions about recovery using data from a prospective study conducted from January 1986 until February 1999 that assessed patients for a period of up to 9 years from their first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

Method

The parent study has been described in detail elsewhere (3–5). Study conduct conformed to the guidelines of the Long Island Jewish Medical Center Institutional Review Board. After a complete explanation of the study, subjects and available family members provided written informed consent. Subjects (N=118) who met Research Diagnostic Criteria (6) for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and who had no more than 12 weeks of lifelong antipsychotic treatment were assessed at baseline, treated according to a standardized medication algorithm, and evaluated prospectively. Subjects progressed from one medication in the algorithm to the next until they responded. The sequence of medications was as follows: fluphenazine, haloperidol, haloperidol plus lithium, either molindone or loxapine, and clozapine. Adjuvant medications (sertraline or lithium) for mood stabilization were used as clinically indicated. Benztropine, lorazepam, and propranolol were prescribed as needed for side effects. The treatment settings were an inpatient unit, day and partial hospital programs, and an outpatient department. In each setting, treatment was administered by the study treatment team (psychiatrist, research social worker, and nurse). In addition to clinical management, there was a psychoeducation program for subjects and family members. Group and individual psychotherapy were provided as needed. Subjects also had access to an extensive range of ancillary services (e.g., rehabilitation services) provided by Zucker Hillside Hospital, a large psychiatric center. Initially, there was no limitation on study duration; later the length of treatment in the study was set at 5 years.

Assessments and Measures

The parent study included many measures; those used in the current analyses were as follows.

Diagnosis

At baseline, patients were interviewed with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) (7). Final study RDC diagnosis for each subject was assigned when the initial episode remitted (or after 1 year of study participation for patients who did not remit). Information sources used were the baseline SADS interview, interviews with family members, longitudinal psychopathology ratings, and clinical data from the treatment team.

Psychopathology

The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Change Version (SADS-C) with psychosis and disorganization items (8) was completed at baseline, every 2 weeks during treatment of acute episodes, and every 4 weeks at other times. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (9) was employed at baseline and every 4 weeks.

Premorbid social adjustment

The Premorbid Adjustment Scale (10) was completed at baseline from information provided by both patients and family members. “Premorbid” was defined as the period ending 6 months before the first psychiatric contact or hospitalization or 6 months before any evidence of florid psychotic symptoms.

Neuropsychological assessments

After stabilization of the initial psychotic episode, subjects were tested with a comprehensive cognitive battery that included 41 tests (11). Tests were grouped to characterize six domains: language, memory, attention, executive function, motor function, and visuospatial function. The mean of these six scales was employed as the global scale. A premorbid cognitive functioning scale was also constructed that was based upon the hypothesis that certain tests of general knowledge, vocabulary, and reading skill are less liable to deteriorate (12, 13). The contribution of test variables to scales was based on an a priori assessment of content validity, similar to methods previously described (12, 14, 15). Scores for each scale were computed by averaging z scores on contributing variables. These z scores were based on the performance of a healthy comparison group (N=36). Higher values on the cognitive scales indicate better performance.

Social adjustment

The Social Adjustment Scale II (16) was used every 6 months to assess this variable.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Brain scans were obtained during the index episode using a 1.0-T whole-body MRI system (Magnetom, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). Images acquired by a three-dimensional gradient echo sequence (coronal acquisition, 3.1-mm thick contiguous slices, with 256×256 matrix in a 24-cm field of view; number of excitations=1; TR=40 msec, TE=15 msec, flip angle=50°) were used for morphometric analysis. A semiautomated mensuration system was used for assessing whole brain, cortical, ventricular, caudate, superior temporal gyrus, and hippocampal volumes (methods described in references 15, 17–19). To examine the effects of regional cerebral volume asymmetry, volumes for prefrontal, premotor, sensorimotor, occipitoparietal, and temporal lobes in each hemisphere were calculated (as described elsewhere [20]). Asymmetry indexes were computed for each region using the formula: ([right volume minus left volume] divided by [right volume plus left volume]) multiplied by 100. Torque, a composite index of cortical asymmetry, was calculated as prefrontal index plus premotor index plus temporal index minus occipitoparietal index minus sensorimotor index. In the calculation formula, the sensorimotor and occipitoparietal indexes were subtracted so that higher positive values of torque indicate a more healthy pattern of asymmetry.

Recovery Criteria

Our recovery measures were derived from the University of California at Los Angeles recovery criteria (21). Full recovery required that subject ratings covering the same period fulfill criteria for both symptom remission and adequate social/vocational functioning. We operationalized the definitions for these components as follows. Symptom remission criteria required both 1) a rating of no worse than “mild” (score=3) for all of the following SADS-C psychosis items: severity of delusions, severity of hallucinations, impaired understandability, derailment, illogical thinking, and bizarre behavior and 2) a rating of no worse than “moderate” (score=3) for the SANS global ratings of affective flattening, alogia, avolition-apathy, and anhedonia-asociality. Adequate social/vocational functioning criteria had three components derived from ratings on the Social Adjustment Scale interview; all components had to be fulfilled to meet criteria. The first component was appropriate role function, defined as paid employment, attending school at least half-time or, if a homemaker, performing that role adequately or better. The second component was the ability to perform day-to-day living tasks without supervision. This entailed personal appearance and grooming that was “reasonable, neat, clean and appropriate” or better and at least adequate functioning as a homemaker or, if not the primary homemaker for the family, a rating of “usually carries out most chores with little difficulty” or better on the performance adequacy (chores) item. The third component was social interactions with a peer outside of the family, defined as social interactions once a week or more with friends or romantic contacts.

Data Analysis

Each subject rating was classified as meeting criteria for full recovery and, separately, for the recovery components of symptom remission and adequate social/vocational functioning.

Recovery rates

Subjects were classified as meeting criteria for symptom remission, adequate social/vocational functioning, or full recovery if their ratings met the appropriate criteria for 2 consecutive years. Cumulative recovery rates were determined by survival analyses that adjusted for differences in duration of follow-up among subjects; 95% confidence intervals (CI) are provided to indicate the precision of these estimated rates.

Predictors of recovery

The recovery rate definitions provide an easy-to-understand summary of clinically meaningful outcomes. However, to explore predictors of recovery, continuous measures of recovery (rather than the dichotomous variables used for the recovery rate analysis) were used in order to minimize information loss. We constructed these continuous measures for the predictor analyses using the entire array of each individual’s ratings and did not require that criteria be maintained for 2 years. For each subject we calculated the proportion of all of their ratings that met the cross-sectional criteria for full recovery. We also calculated the same proportions separately for the symptom remission component and for the adequate social/vocational functioning component of the recovery criteria.

Regression analysis (backward elimination) was used to study the relative contributions of various predictors to the percent of the total number of ratings for each subject that met criteria for symptom remission, adequate social/vocational functioning, and full recovery. The set of potential explanatory variables consisted of demographic, clinical, cognitive, and MRI measures. Selection of variables for the regression models was based on correlational analyses. Variables were included in the models if they were significantly correlated at the p<0.05 level with symptom remission, adequate social/vocational functioning, or full recovery.

Results

Subject Characteristics

Fifty-two percent of the 118 subjects were men. Mean age at study entry was 25.2 years (SD=6.6). Subjects were from diverse ethnic backgrounds (Caucasian: 41% [N=48]; African American: 37% [N=44]; Hispanic: 12% [N=14]; Asian: 7% [N=8]; mixed background: 3% [N=4]). They came primarily from the middle class or below. The mean parental social position on the Hollingshead Redlich scale (22) was 3.4 (SD=1.3). Seventy percent of subjects were diagnosed with schizophrenia and 30% with schizoaffective disorder. They were severely ill at study entry (mean score on the Global Assessment Scale [23] at study entry was 27.1, SD=9.0). Subjects were treated in the study for a mean of 221 weeks (SD=106).

Recovery Rates

Cumulative recovery rates are presented in Table 1. Approximately half of the subjects experienced symptom remission for 2 years or more by the end of 5 years of follow-up. However, only one-quarter of subjects achieved sustained adequate social and vocational functioning, and only about one-eighth met full recovery criteria for 2 years or more during their time in the study. The mean percent of each subject’s ratings meeting the cross-sectional symptom remission criteria, adequate social/vocational functioning criteria, and full recovery criteria was 65.7% (SD=32.4%), 38.0% (SD=31.8%), and 30.3% (SD=31.1%), respectively.

Predictors of Recovery

The same set of variables was used in the three regression analyses to predict the recovery outcomes because we wished to be able to compare the predictors across outcomes. Because of protocol modifications during the long course of the study or subject refusal, data on potential predictor variables were not available on all subjects. The cognitive variables had the sparsest data (N=94), constraining the observations used in the regression analyses. (The Ns ranged from 108 to 118 for the demographic variables, 101 to 118 for the clinical variables, and 96 to 107 for the MRI variables.)

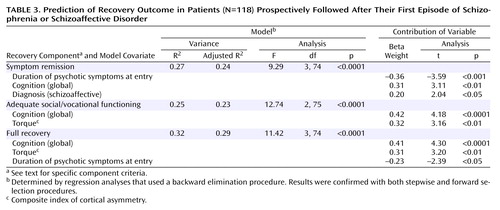

Pearson correlations between the recovery measures and the predictor variables are presented in Table 2. Many of the cognitive variables were highly correlated with the outcome variables. The high raw correlations for the cognitive variables, multicollinearity analyses, and parsimony led us to choose the global measure of cognition as the only cognitive predictor variable in our analyses. In making this selection, we were guided by our interest in determining the relative contributions of predictors from different domains, not simply that cognitive variables are significant predictors of recovery. The final set of variables used in the model for the prediction of each recovery outcome were: gender, best premorbid social functioning, duration of psychotic symptoms before study entry, diagnosis, mean severity of hallucinations and delusions after 4 weeks of antipsychotic treatment, percentage of time taking antipsychotic medication, global cognition score, lateral ventricle volume (total), superior temporal gyrus volume (total), and torque (the use of either total or right lateral ventricle volume did not change the final models). The results of the backward elimination procedure were confirmed with both stepwise and forward selection procedures.

The results of these analyses are presented in Table 3. R2 values for these analyses are quite substantial, ranging from R2=0.25 to 0.32 (adjusted R2=0.23 to 0.29). Better cognitive functioning predicted symptom remission, adequate social/vocational functioning, and full recovery. Shorter duration of psychosis before study entry predicted both symptom remission and full recovery. More normal cerebral asymmetry was associated with adequate social/vocational functioning and full recovery. A schizoaffective diagnosis predicted symptom remission.

Discussion

Our subjects did well in terms of control of positive and negative symptoms, the usual measure of response in treatment studies. Approximately half had symptom remission for 2 years or longer. However, only a quarter of the subjects achieved sustained social/vocational recovery, and only 13.7% met criteria for full recovery. Direct comparison of our rates with those from the long-term follow-up studies is precluded by the very substantial differences in study design and outcome criteria. However, our data are consistent with the findings from the long-term studies in that some patients with schizophrenia can achieve both symptom remission and appropriate social/vocational functioning.

In evaluating our recovery rates, it is important to consider that the level of vocational and social functioning required by our criteria would not be met by some members of the general public who do not have a psychiatric disorder. Further, although early course may predict long-term course (2), long-term follow-up studies (1, 2) have consistently found a subgroup of subjects who recover after many years of severe illness. Our recovery rates may therefore underestimate the percentage of our subjects who eventually recover. Nonetheless, the very low rate of full recovery during our study observational period, despite what we believe was excellent treatment in a research team setting, highlights the importance of continuing efforts to develop treatments designed to improve the initial course of patients with schizophrenia.

We found specific predictors of recovery. Better cognitive performance was associated with full recovery and both the adequate social/vocational functioning and symptom remission components of recovery. The other two variables associated with full recovery, torque and duration of psychotic symptoms at study entry, were associated with only one of the recovery components. More cerebral asymmetry was associated with adequate social/vocational functioning, and duration of psychotic symptoms at study entry was associated with symptom remission. Elucidating the mechanisms underlying these associations may provide a basis for later development of interventions to promote recovery.

Our findings about the association between cognition and recovery are consistent with data from other studies relating cognitive performance and social/vocational outcome (reviewed in references 24, 25). However, relationships between cognitive performance and symptom outcomes have been much less recognized. In previous analyses of data from our parent study, relationships between cognitive performance and symptom outcomes were not consistent. Measures of attention were related to acute treatment response (4), but cognitive performance was not related to relapse following initial symptom remission (5). What may have contributed to our ability to detect the relationships between cognitive variables and symptom remission in the current analyses? One possibility is that our symptom remission criteria differed from most symptom outcome measures in 1) requiring a fixed level of improvement in both positive and negative symptoms and 2) assessing outcome over an extended period.

Regarding our other predictors, our finding of a relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and symptom remission is consistent with findings from many, but not all, studies of duration of untreated psychosis and treatment response (reviewed in reference 26). Our findings also indicate an association with full recovery. The association between symptom remission and the diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder is consistent with earlier studies (2, 27, 28) that found that patients with schizoaffective disorder have less severe residual symptoms than patients with schizophrenia. Abnormalities in brain asymmetries have been found in many studies of schizophrenia (reviewed in reference 29) and have been postulated to be a core feature of the disorder by some investigators (30). Neurodevelopmental abnormalities have been implicated as the cause of the decrease in cerebral volume asymmetry found in schizophrenia. In a previous analysis (20) of a subset of the current sample, measures of torque were not associated with acute treatment response, but lower torque values were associated with more negative symptoms at baseline in men. Our results suggest an association with full recovery and longer-term social/vocational functioning.

Two variables not associated with our recovery measures deserve mention. Medication discontinuation was strongly associated with relapse in earlier analyses with our sample (5). Although many subjects stopped medication at some point in our study, long-term medication adherence was very high, since subjects usually resumed medication following staff interventions or the return of symptoms. This limited our ability to detect medication effects on outcome and probably accounts for the lack of association between medication use and symptom remission in the current analyses. Ho and colleagues (31) found that baseline negative symptoms predicted social/vocational outcomes at 2-year follow-up in a sample of 50 subjects with first-episode schizophrenia. In our analyses, more severe baseline negative symptoms were associated with poorer outcomes, but the correlations were not significant. The divergent findings from the two studies may result from differences in the outcome measures and the period covered by the assessments. The assessment period may be critical in studies of negative symptoms in first-episode schizophrenia, since the pattern of negative symptoms may still be evolving at this stage of the illness. This was highlighted by an earlier analysis (32) of the first 70 subjects in our sample. Severity of baseline negative symptoms did not predict which subjects later developed persistent negative symptoms.

In summary, patients with first-episode schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder can recover. However, the low rate of recovery during the early years of the illness highlights the need for continued efforts to develop better treatments to promote recovery by patients with schizophrenia.

|

|

|

Presented in part at the 41st annual meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, San Juan, Puerto Rico, December 8–12, 2002. Received Feb. 11, 2003; revision received Aug. 11, 2003; accepted Aug. 14, 2003. From the Department of Psychiatry Research, the Zucker Hillside Hospital; the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, N.Y.; and the Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. Address reprint requests to Dr. Robinson, Research Department, Zucker Hillside Hospital, 75-59 263rd St., Glen Oaks, NY 11004; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants MH-41646, MH-00537, MH-60004, and MH-41960 for the Hillside Center for Intervention Research in Schizophrenia and by NIH General Clinical Research Center grant RR-018535 for the North Shore-Long Island Jewish Research Institute. The authors thank the research staff members who contributed to the project and provided the data for the analyses. They also thank the project subjects and their family members for their study participation and Nina Schooler, Ph.D., Gwenn Smith, Ph.D., and Martin Lesser, Ph.D., for providing comments about the manuscript. The principal investigators for this project were Jeffrey Lieberman, M.D. (1986–1996) and John Kane, M.D. (1996–1999). Jose Ma. J. Alvir, Dr.P.H., devised the original database structure for the study.

1. Harding CM: Course types in schizophrenia: an analysis of European and American studies. Schizophr Bull 1988; 14:633–643Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T, Laska E, Siegel C, Wanderling J, Dube KC, Ganev K, Giel R, an der Heiden W, Holmberg SK, Janca A, Lee PW, Leon CA, Malhotra S, Marsella AJ, Nakane Y, Sartorius N, Shen Y, Skoda C, Thara R, Tsirkin SJ, Varma VK, Walsh D, Wiersma D: Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 178:506–517Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, Woerner M, Degreef G, Bilder RM, Ashtari M, Bogerts B, Mayerhoff DI, Geisler SH, Loebel A, Levy DL, Hinrichsen G, Szymanski S, Chakos M, Koreen A, Borenstein M, Kane JM: Prospective study of psychobiology in first-episode schizophrenia at Hillside Hospital. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:351–371Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Alvir JMJ, Geisler S, Koreen A, Sheitman B, Chakos M, Mayerhoff D, Bilder R, Goldman R, Lieberman JA: Predictors of treatment response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:544–549Link, Google Scholar

5. Robinson D, Woerner M, Alvir JMJ, Bilder R, Goldman R, Geisler S, Koreen A, Sheitman B, Chakos M, Mayerhoff D, Lieberman JA: Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:241–247Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) for a Selected Group of Functional Disorders, 3rd ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1977Google Scholar

7. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:837–844Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Spitzer RL, Endicott J: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Change Version, 3rd ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1978Google Scholar

9. Andreasen NC, Olsen S: Negative v positive schizophrenia: definition and validation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:789–794Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Cannon-Spoor HE, Potkin SG, Wyatt RJ: Measurement of premorbid adjustment in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1982; 8:470–484Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Bilder RM, Goldman RS, Robinson D, Reiter G, Bell L, Bates JA, Pappadopulos E, Willson DF, Alvir JMJ, Woerner MG, Geisler S, Kane JM, Lieberman JA: Neuropsychology of first-episode schizophrenia: initial characterization and clinical correlates. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:549–559Link, Google Scholar

12. Bilder RM, Degreef G, Pandurangi AK, Rieder RO, Sackeim HA, Mukherjee S: Neuropsychological deterioration and CT-scan findings in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1988; 1:37–45Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Bilder RM, Lipschutz-Broch L, Reiter G, Geisler SH, Mayerhoff DI, Lieberman JA: Intellectual deficits in first-episode schizophrenia: evidence for progressive deterioration. Schizophr Res 1992; 18:437–448Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Bilder RM, Mukherjee S, Rieder RO, Pandurangi AK: Symptomatic and neuropsychological components of defect states. Schizophr Res 1985; 11:409–419Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Bilder RM, Bogerts B, Ashtari M, Wu H, Alvir JM, Jody D, Reiter G, Bell L, Lieberman JA: Anterior hippocampal volume reductions predict “frontal lobe” dysfunction in first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1995; 17:47–58Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Schooler NR, Hogarty GE, Weissman MM: Social Adjustment Scale II (SAS), in Resource Materials for Community Health Program Evaluations, 2nd ed. Publication ADM 79–328. Edited by Hargreaves WP, Attkisson CC, Sorenson JE. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health, Education and Welfare, 1979, pp 290–302Google Scholar

17. Lieberman JA, Jody D, Alvir JM, Ashtari M, Levy D, Bogerts B, Degreef G, Mayerhoff DI, Cooper T: Brain morphology, dopamine, and eye-tracking abnormalities in first-episode schizophrenia: prevalence and clinical correlates. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:357–368Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Degreef G, Ashtari M, Bogerts B, Bilder RM, Jody DN, Alvir JMJ, Lieberman JA: Volumes of ventricular system subdivisions measured from magnetic resonance images in first-episode schizophrenic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:531–537Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Chakos MH, Lieberman JA, Bilder RM, Borenstein M, Lerner G, Bogerts B, Wu H, Kinon B, Ashtari M: Increase in caudate nuclei volumes of first-episode schizophrenic patients taking antipsychotic drugs. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1430–1436Link, Google Scholar

20. Bilder RM, Wu H, Bogerts B, Degreef G, Ashtari M, Alvir JM, Snyder PJ, Lieberman JA: Absence of regional hemispheric volume asymmetries in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1437–1447Link, Google Scholar

21. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, Gutkind D: Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry 2002; 14:256–272Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Hollingshead AB: Two-Factor Index of Social Position. New Haven, Conn, Yale University, 1965Google Scholar

23. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:766–771Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J: Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophr Bull 2000; 26:119–136Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:321–330Link, Google Scholar

26. Norman RM, Malla AK: Duration of untreated psychosis: a critical examination of the concept and its importance. Psychol Med 2001; 31:381–400Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Opjordsmoen S: Long-term course and outcome in unipolar affective and schizoaffective psychoses. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989; 79:317–326Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Grossman LS, Harrow M, Goldberg JF, Fichtner CG: Outcome of schizoaffective disorder at two long-term follow-ups: comparisons with outcome of schizophrenia and affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1359–1365Link, Google Scholar

29. Petty RG: Structural asymmetries of the human brain and their disturbance in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1999; 25:121–139Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Crow TJ, Ball J, Bloom SR, Brown R, Bruton CJ, Colter N, Frith CD, Johnstone EC, Owens DG, Roberts GW: Schizophrenia as an anomaly of development of cerebral asymmetry: a postmortem study and a proposal concerning the genetic basis of the disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:1145–1150Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Ho B-C, Nopoulos P, Flaum M, Arndt S, Andreasen NC: Two-year outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: predictive value of symptoms for quality of life. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1196–1201Link, Google Scholar

32. Mayerhoff DI, Loebel AD, Alvir JMJ, Szymanski SR, Geisler SH, Borenstein M, Lieberman JA: The deficit state in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1417–1422Link, Google Scholar