Cost-Utility Analysis Studies of Depression Management: A Systematic Review

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Depression is common, costly, treatable, and a major influence on quality of life. Cost-utility analysis combines costs with quantity and quality of life into a metric that is meaningful for studies of interventions or care strategies and is directly comparable to measures in other such studies. The objectives of this study were to identify published cost-utility analyses of depression screening, pharmacologic treatment, nonpharmacologic therapy, and care management; to summarize the results of these studies in an accessible format; to examine the analytic methods employed; and to identify areas in the depression literature that merit cost-utility analysis. METHOD: The authors selected articles regarding cost-utility analysis of depression management from the Harvard Center for Risk Analysis Cost-Effectiveness Registry. Characteristics of the publications, including study methods and analysis, were examined. Cost-utility ratios for interventions were arranged in a league table. RESULTS: Of the 539 cost-utility analyses in the registry, nine (1.7%) were of depression management. Methods for determining utilities and the source of the data varied. Markov models or cohort simulations were the most common analytic techniques. Pharmacologic interventions generally had lower costs per quality-adjusted life year than nonpharmacologic interventions. Psychotherapy alone, care management alone, and psychotherapy plus care management all had lower costs per quality-adjusted life year than usual care. Depression screening and treatment appeared to fall within the cost-utility ranges accepted for common nonpsychiatric medical conditions. CONCLUSIONS: There is a paucity of literature on cost-utility analysis of depression management. High-quality cost-utility analysis should be considered for further research in depression management.

Depression is a common and costly problem. In the United States, major depressive disorder affects 16.2% of adults in the course of their lifetimes (1). The World Health Organization’s report of 2001 ranked depression as “the fourth leading cause of burden among all diseases, accounting for 4.4% of total disability-adjusted life years, and the leading cause of years lived with disability, accounting for 11.9% of disability years” (2).

Research has demonstrated the effectiveness of several types of depression intervention. Depression frequently goes unrecognized in primary care, but screening has been shown to increase detection and can lead to improved outcomes when linked to adequate treatment (3). The efficacy of both cognitive behavior therapy and pharmacologic treatment is established (4–6). Care management such as the collaborative care model, a system-based intervention using education, consultation, and follow-up, has been shown to improve the quality and outcomes of pharmacologic treatment (7–9).

The direct costs of depression are related to diagnostic and therapeutic contacts (e.g., visits to physicians) and treatment, both medication and counseling. Treatment is costly, as either person time is required for counseling or medications must be purchased. The latter is of particular concern, as use of antidepressant medications, particularly newer agents, is on the rise (10–13). Most of these newer agents do not have generic alternatives and are among the more expensive of the top 200 drugs prescribed (14). There are also substantive indirect costs of depressive illness. Unemployment and loss of income are more likely among those suffering from depression (15). Nearly half of lost productivity in the United States is due to major depression, with an estimated cost of $44 billion annually (16). Depression is also associated with increased medical utilization (17), increased costs for other health conditions (17, 18), worse long-term outcomes (19–23), and worse adherence to medication regimens (24).

Cost-utility analysis is a type of cost-effectiveness analysis that examines the costs and effectiveness of therapies by using the quality-adjusted life year as its unit of effectiveness. Cost-utility analyses examine the effects of interventions on both quantity and quality of life, allowing not only comparison across a broad array of interventions for the same condition but also comparison of interventions across different conditions. Cost-utility analyses therefore are considered the gold standard both for reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses in the literature and for informing policy decisions on the broader allocation of health care resources (25–28). Determining the cost-utility of depression care can shed light on alternative strategies for managing the condition. Cost-utility data can also inform debates on policy and financing issues, such as proposed legislation establishing parity in coverage between mental health and other types of medical care. The examination of cost per quality-adjusted life year in a cost-utility analysis is particularly relevant to depression because of the marked impact of the disorder on quality of life (29–33).

To our knowledge, no systematic review of the peer-reviewed cost-utility literature in depression has been published to date. We undertook this systematic review 1) to identify published cost-utility analyses of depression management (i.e., screening, pharmacologic treatment, psychotherapy, care management), 2) to summarize the results of these studies in an accessible format, 3) to examine the analytic methods employed, and 4) to identify areas in the depression literature that merit further study with cost-utility analysis.

Method

This review was done as part of a larger project to systematically review cost-utility analyses in medicine (34). All 539 cost-utility analyses published in the medical literature from 1976 through 2001 have been compiled into a cost-effectiveness analysis registry that is available on the Internet as a public use file (http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/cearegistry). The method by which studies were identified, selected, and evaluated for the registry is reported elsewhere (34–36). The current study focuses on cost-utility analyses of depression management in the registry database.

Data Collection and Presentation

For each cost-utility analysis, the descriptive characteristics collected were year of publication, country of origin, intervention type, publication journal type, and study funding source. The methodological and analytic characteristics included the study perspective, sources of preference (or utility) data, discounting of future costs and quality-adjusted life years, inclusion of productivity costs, consideration of patient adherence to the intervention, and performance of sensitivity analyses.

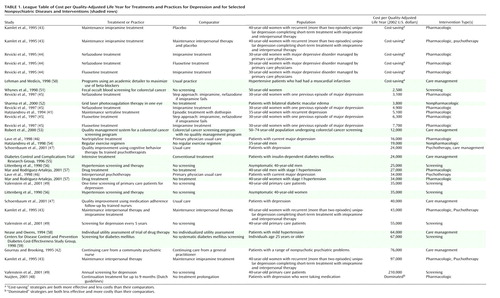

A league table is an easily accessible means of presenting cost-utility ratios for comparison (34). The league table includes a description of the intervention, the comparator (the alternative treatment), the target population, and the cost-utility ratio in dollars per quality-adjusted life year. We created a league table of the cost-utility ratios presented in the published cost-utility analyses for depression. All of the ratios were standardized to 2002 U.S. dollars by using foreign exchange factors (37–39) and the general consumer price index (40).

In addition to depression cost-utility analyses, we also wanted to provide some reference by including some cost-utility analyses of other diseases and practices. To do this, we reviewed the cost-effectiveness analysis registry for studies of screening, pharmacologic treatments, nonpharmacologic treatments, and care management efforts for coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes, and colon cancer in which the comparator was placebo or usual care. We then chose ratios that we felt would be most useful for putting the depression cost-utility analyses into a broader perspective.

Definitions of Terminology in Cost-Utility Analysis

It is important to distinguish between cost-effectiveness and cost-utility. Cost-effectiveness analysis is a technique by which the cost and effects of an intervention and an alternative are presented in a ratio of incremental cost to incremental effect, whereas cost-utility analyses are a subset of cost-effectiveness analyses that combine both the quality of life and the mortality benefits of an intervention in one common metric, the quality-adjusted life year. Quality of life is measured in utilities, which are preferences (or values) for health states. The utilities for a given health state can be measured by different populations, such as patients, proxies, clinicians, or a sample of the general public. Of note, as with cost-effectiveness analysis, lower ratios for cost-utility analysis are more favorable; the most favorable is cost saving, where the intervention is more effective and costs less than the alternative. “Dominated” strategies are both less effective and more costly than their comparators.

Perspective refers to the viewpoint from which costs and effects are valued. The gold standard in the literature is to report cost-utility analyses from the societal perspective, valuing all costs and effects in order to best guide the allocation of societal resources (25, 27). Discounting is the conversion to their present value of future dollars spent and future health outcomes accrued. Last, it is important to determine the impact of changing one or several variables in a model or analysis on the outcome of the analysis. A sensitivity analysis allows a range of plausible inputs to be considered when there is uncertainty about the true value of an input.

Results

Systematic review of the cost-utility literature identified 539 studies published between 1976 and 2001 that examined cost per quality-adjusted life year. However, only nine (1.7%) of these 539 cost-utility analyses examined the management of depression (41–49). In the aggregate, these nine analyses presented 21 cost-utility ratios. The earliest publication of a cost-utility analysis of depression management was in 1994. Five of the articles came from the United States, two from the United Kingdom, and one each from Canada and the Netherlands. They were published in a variety of journals; four were published in general medical journals, two in clinical specialty journals, and three in methodological or economic journals. Five studies were government funded; one of these was cofunded by a foundation. Pharmaceutical companies funded three cost-utility analyses. For one study the funding source was not stated.

There was a great deal of variety in the analytic methods employed in the nine cost-utility analyses. Three took a societal perspective, three took a health care sector or third-party payer perspective, and three did not state their perspectives. The preference determinations for the utilities were not mutually exclusive in the reviewed studies: three used those derived from the community, five from patients, and three from the authors or clinicians. Preference determination was not stated in one study. Of the nine analyses, seven discounted future costs and quality-adjusted life years, four included productivity costs, and six considered patient adherence to the interventions. Sensitivity analysis was tested for effectiveness in eight studies, for cost in six, for discount rate in six, and for quality of life in four. One study did not perform any sensitivity analysis. Markov models or cohort simulations were the most common analytic techniques.

The 21 cost-utility ratios for depression interventions are found in Table 1. In addition, selected cost-utility ratios for other diseases and interventions included for comparison are displayed with shading. For the depression cost-utility analyses, three ratios involved screening, 14 evaluated pharmacologic strategies, five examined psychotherapy, and three tested care management strategies. One-time screening for depression in primary care had a favorable cost-utility ratio, but screening every 5 years was at a marginally high cost per quality-adjusted life year ($55,000), and annual screening came at a high cost per quality-adjusted life year ($210,000). All but two of the ratios for comparisons of pharmacologic interventions to other interventions (e.g., placebo, psychotherapy, an older antidepressant agent) had costs per quality-adjusted life year below the often-used cutoff of $50,000 per quality-adjusted life year. Psychotherapy alone or as part of a case management effort was superior to usual care (at $24,000 to $34,000 per quality-adjusted life year), but maintenance imipramine treatment had a favorable cost per quality-adjusted life year when compared to maintenance psychotherapy plus placebo. Care management efforts, when compared to usual practice, had costs per quality-adjusted life year ranging from $24,000 to $76,000.

Discussion

Despite the well-documented impact of depression on health outcomes and costs, we found few published depression cost-utility analyses, representing only 1.7% of the 539 cost-utility analyses in health and medicine published over 25 years. The 2001 report of the World Health Organization projected that by 2020, only ischemic heart disease will account for more lost disability-adjusted life years than depression (2). As of 2001, the number of cost-utility analyses of treatments for ischemic heart disease far outnumbered those for depression.

Interest in data on the value of health services is growing, as demonstrated by the recent consideration in the U.S. Congress of the use of comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness to determine reimbursement (60). For this reason, disease-specific comparative league tables, along with assessments of the methodological rigor employed by the included studies, will be more common practice as we determine how best to care for patients. Examination of our league table indicates that compared to no screening, one-time screening came at a relatively low cost per quality-adjusted life year, while screening every 5 years and annual screening did not. Pharmacologic therapies had the lowest cost per quality-adjusted life year among depression interventions in the cost-utility analysis literature. Psychotherapy had a lower cost per quality-adjusted life year than usual care. However, pharmacologic treatment, either alone or in combination with psychotherapy, had a lower cost per quality-adjusted life year than psychotherapy alone. Of the care management strategies, all of which were compared to usual or typical care, quality improvement using trained psychotherapists and medication follow-up with trained nurses came at a reasonable cost per quality-adjusted life year, while continuing care from a community psychiatric nurse had a high cost per quality-adjusted life year.

Cost-utility ratios for active interventions in depression screening or care may be difficult to consider in the same context as ratios from cost-utility analyses for other disease areas. However, by focusing on ratios based on a comparator of placebo or usual care, we can get a sense of how the cost-effectiveness of some practices for depression compares to that for other diseases. Although not meant to represent definitive comparisons of depression screening, treatment, and management with practices for such conditions as coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes, and colon cancer, we feel these selected ratios give some context to the cost-utility ratios for depression. Examination of these ratios gives a sense that the costs per quality-adjusted life year for screening, pharmacologic treatment, nonpharmacologic treatment, and care management for depression are well within the acceptable range for screening or care of these other diseases. Comparative cost-utility data that place the management of depression in the context of other medical illnesses will help inform public and private sector debates about parity in insurance coverage for psychiatric conditions and could promote greater use of screening, care management, and other methods of improving care.

Limitations of our analysis of the cost-utility literature must be acknowledged; some specific to our methods have been discussed elsewhere (34, 35, 61). Our review included only studies conducted through 2001, but we have identified only one further study of cost-utility in depression after 2001 (62). Comparison of the practices and treatments may not have been apt given the potentially wide variation in characteristics, such as duration of follow-up, source of costs, source of utilities, and country of origin. While the strategy for identification, review, and inclusion in the cost-utility registry was rigorous, it is possible that some studies were not included. It is important to note that for many studies examining the cost-effectiveness of treatments for depression, the investigators did not consider or report on utilities in their analyses, while others mentioned cost-utility analysis in their discussion sections but did not provide the detail required to include them in the registry (63, 64). We focused on cost-utility analysis, as this is the recommended method for economic evaluation of health care (27), so reports on cost-effectiveness analyses that did not explicitly present cost per quality-adjusted life year were not included in the registry. The review of the articles included in the registry was not blinded, so bias could have been introduced. Last, the ratios we present are not static, as changes in the costs of the interventions can substantially alter their cost per quality-adjusted life year. These might occur with changes such as policy shifts, use of generic as opposed to branded medications, and alterations in pharmacy benefits management.

Given the high burden of disease due to depression and the small number of cost-utility analyses in this area, more research using cost-utility analysis is needed. The cost-effectiveness of newer antidepressant agents, such as mirtazapine and venlafaxine, has been reported to be superior to that of tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (65–67), but these studies were done without consideration of utilities. Such a finding from cost-utility analysis would be of particular interest, given that use of some newer antidepressants may be associated with more frequent and more rapid remission of depression (68), which in turn might lead to better long-term outcomes, including quality of life, at better value. Similarly, other antidepressants may have fewer drug-drug interactions (69), a property that might lower the cost of depression treatment among patients who take other medications. There has been increasing appreciation of the significance of the interaction of depression and chronic medical illness (70). Some work has indicated increased costs in other chronic illnesses that are attributable to depression (71), but we know of no published cost-utility analyses of depression treatment in patients with chronic comorbid medical illness. Novel strategies for depression, such as self-help strategies (72) and stepped behavioral models, are other areas to which cost-utility analysis might be extended.

Given the variability in the methods of the work we reviewed, future cost-utility analyses in depression would benefit from adoption of standards that would both raise the quality of the studies and allow for easier comparison of cost-utility ratios. Among these should be study design based on a societal perspective, a standard approach to determining utilities with weights representing patient or community preferences, including net costs, reporting of incremental comparisons, and discounting of costs and quality-adjusted life years (25–28). Use of a target population from whom findings could be applied to a more general population might also be considered. As in any research, it is important to have an impartial funding source so as to maintain the integrity of the work. All cost-utility analyses would benefit from following these quality recommendations. However, the cost-utility analysis literature on depression management stands to benefit even more because so little currently exists. Therefore, each new cost-utility analysis of depression management that applies rigorous methods and standards will assure that the majority of this body of literature will be of high quality, allowing for even better assessment and comparison of cost-effective practices in depression.

Depression is common, costly, treatable, and a major influence on the quality of life. Cost-utility analysis combines these characteristics into a metric that is both meaningful for a sole study of a practice or treatment and allows direct comparison to other such studies. We have reviewed the literature on cost-utility analyses of screening and treatment of depression, and we found that pharmacologic treatments appear to be the interventions with the lowest cost per quality-adjusted life year. Broadly speaking, depression screening and care appeared to fall within the cost-utility ranges accepted for other common nonpsychiatric medical diseases. Perhaps most striking is the paucity of cost-utility research in depression. Given the suitability of cost-utility analysis for assessing depression care, this finding represents a call to action among those doing depression research to seriously consider including such analyses in the design of future work.

|

Received Nov. 24, 2003; revision received Feb. 23, 2004; accepted March 10, 2004. From the Division of General Internal Medicine, Rhode Island Hospital, Brown Medical School; the Program on the Economic Evaluation of Medical Technology, Harvard Center for Risk Analysis, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston; the Division of General Medicine and Primary Care, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston; and the Department of Psychiatry, the Health Institute, Tufts-New England Medical Center, Boston. Address reprint requests to Dr. Pirraglia, Rhode Island Hospital, 593 Eddy St., MPB-1, Providence, RI 02903; [email protected] (e-mail).

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang PS: The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003; 289:3095–3105Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. The World Health Report 2001: Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2001, p 30Google Scholar

3. US Preventive Services Task Force: Screening for Depression: Recommendations and Rationale. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, May 2002. http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/3rduspstf/depression/depressrr.htmGoogle Scholar

4. Steffens DC, Krishnan KR, Helms MJ: Are SSRIs better than TCAs? comparison of SSRIs and TCAs: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety 1997; 6:10–18Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. DeRubeis RJ, Galfand LA, Tang TZ, Simons AD: Medications versus cognitive behavior therapy for severely depressed outpatients: mega-analysis of four randomized comparisons. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1007–1013Abstract, Google Scholar

6. MacGillivray S, Arroll B, Hatcher S, Ogston S, Reid I, Sullivan F, Williams B, Crombie I: Efficacy and tolerability of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors compared with tricyclic antidepressants in depression treated in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br Med J 2003; 326:1014–1017Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Walker E, Simon GE, Bush T, Robinson P, Russo J: Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA 1995; 273:1026–1031Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Boudreau DM, Capoccia KL, Sullivan SD, Blough DK, Ellsworth AJ, Clark DL, Katon WJ, Walker EA, Stevens NG: Collaborative care model to improve outcomes in major depression. Ann Pharmacother 2002; 36:585–591Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Hedrick SC, Chaney EF, Felker B, Liu CF, Hasenberg N, Heagerty P, Buchanan J, Bagala R, Greenberg D, Paden G, Fihn SD, Katon W: Effectiveness of collaborative care depression treatment in Veterans’ Affairs primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2003; 18:9–16Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Sclar DA, Robinson LM, Skaer TL, Galin RS: Trends in the prescribing of antidepressant pharmacotherapy: office-based visits, 1990–1995. Clin Ther 1998; 20:871–884, 870Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Pincus HA, Tanielian TL, Marcus SC, Olfson M, Zarin DA, Thompson J, Magno Zito J: Prescribing trends in psychotropic medications: primary care, psychiatry, and other medical specialties. JAMA 1998; 279:526–531Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, Elinson L, Tanielian T, Pincus HA: National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA 2002; 287:203–209Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Pirraglia PA, Stafford RS, Singer DE: Trends in prescribing of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors and other newer antidepressant agents in adult primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 5:153–157Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Pharmaceutical Care Network:2002 Pharmacy Benchmarks: Trends in Pharmacy Benefit Management for Commercial Plans. http://www.pharmcarenet.com/pdf/benchmarks_commercial_2002.pdfGoogle Scholar

15. Whooley MA, Kiefe CI, Chesney MA, Markovitz JH, Matthews K, Hulley SB: Depressive symptoms, unemployment, and loss of income: the CARDIA Study. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162:2614–2620Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Hahn SR, Morganstein D: Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. JAMA 2003; 289:3135–3144Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Karlsson H, Lehtinen V, Joukamaa M: Psychiatric morbidity among frequent attender patients in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1995; 17:19–25Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Luber MP, Hollenberg JP, Williams-Russo P, DiDomenico TN, Meyers BS, Alexopoulos GS, Charlson ME: Diagnosis, treatment, comorbidity, and resource utilization of depressed patients in a general medical practice. Int J Psychiatry Med 2000; 30:1–13Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Berkman LF, Berkman CS, Kasl S, Freeman DH Jr, Leo L, Ostfeld AM, Cornoni-Huntley J, Brody JA: Depressive symptoms in relation to physical health and functioning in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol 1986; 124:372–388Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Wassertheil-Smoller S, Applegate WB, Berge K, Chang CJ, Davis BR, Grimm R Jr, Kostis J, Pressel S, Schron E (Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Cooperative Research Group): Change in depression as a precursor of cardiovascular events. Arch Intern Med 1996; 156:553–561Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Whooley MA, Browner WS (Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group): Association between depressive symptoms and mortality in older women. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158:2129–2135Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Juneau M, Talajic M, Bourassa MG: Gender, depression, and one-year prognosis after myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med 1999; 61:26–37Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Peterson JC, Charlson ME, Williams-Russo P, Krieger KH, Pirraglia PA, Meyers BS, Alexopoulos GS: New postoperative depressive symptoms and long-term cardiac outcomes after coronary artery bypass surgery. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 10:192–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW: Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:2101–2107Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Gold M: Panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. Med Care 1996; 34(12 suppl):DS197-DS199Google Scholar

26. Siegel JE, Weinstein MC, Russell LB, Gold MR (Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine): Recommendations for reporting cost-effectiveness analyses. JAMA 1996; 276:1339–1341Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Weinstein MC, Siegel JE, Gold MR, Kamlet MS, Russell LB: Recommendations of the Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA 1996; 276:1253–1258Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Russell LB, Gold MR, Siegel JE, Daniels N, Weinstein MC (Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine): The role of cost-effectiveness analysis in health and medicine. JAMA 1996; 276:1172–1177Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Atkinson M, Zibin S, Chuang H: Characterizing quality of life among patients with chronic mental illness: a critical examination of the self-report methodology. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:99–105Link, Google Scholar

30. Leidy NK, Palmer C, Murray M, Robb J, Revicki DA: Health-related quality of life assessment in euthymic and depressed patients with bipolar disorder: psychometric performance of four self-report measures. J Affect Disord 1998; 48:207–214Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Simon GE, Katon W, Rutter C, VonKorff M, Lin E, Robinson P, Bush T, Walker EA, Ludman E, Russo J: Impact of improved depression treatment in primary care on daily functioning and disability. Psychol Med 1998; 28:693–701Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Ormel J, Vonkorff M, Oldehinkel AJ, Simon G, Tiemens BG, Ustun TB: Onset of disability in depressed and non-depressed primary care patients. Psychol Med 1999; 29:847–853Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Ravindran AV, Matheson K, Griffiths J, Merali Z, Anisman H: Stress, coping, uplifts, and quality of life in subtypes of depression: a conceptual frame and emerging data. J Affect Disord 2002; 71:121–130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Chapman RH, Stone PW, Sandberg EA, Bell C, Neumann PJ: A comprehensive league table of cost-utility ratios and a sub-table of “panel-worthy” studies. Med Decis Making 2000; 20:451–467Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Bell CM, Chapman RH, Stone PW, Sandberg EA, Neumann PJ: An off-the-shelf help list: a comprehensive catalog of preference scores from published cost-utility analyses. Med Decis Making 2001; 21:288–294Medline, Google Scholar

36. Neumann PJ, Stone PW, Chapman RH, Sandberg EA, Bell CM: The quality of reporting in published cost-utility analyses, 1976–1997. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132:964–972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Federal Reserve: Foreign Exchange Rates. http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/H10/hist/default1999.htmGoogle Scholar

38. Saint Louis Federal Reserve: Economic Data—FRED II. http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred/data/exchange.html#exchangeGoogle Scholar

39. x-rates.com. http://www.x-rates.comGoogle Scholar

40. US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics: Consumer Price Indexes. http://www.bls.gov/cpi/home.htmGoogle Scholar

41. Hatziandreu EJ, Brown RE, Revicki DA, Turner R, Martindale J, Levine S, Siegel JE: Cost utility of maintenance treatment of recurrent depression with sertraline versus episodic treatment with dothiepin. Pharmacoeconomics 1994; 5:249–268Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Gournay K, Brooking J: The community psychiatric nurse in primary care: an economic analysis. J Adv Nurs 1995; 22:769–778Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Kamlet MS, Paul N, Greenhouse J, Kupfer D, Frank E, Wade M: Cost utility analysis of maintenance treatment for recurrent depression. Control Clin Trials 1995; 16:17–40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Revicki DA, Brown RE, Palmer W, Bakish D, Rosser WW, Anton SF, Feeny D: Modelling the cost effectiveness of antidepressant treatment in primary care. Pharmacoeconomics 1995; 8:524–540Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Revicki DA, Brown RE, Keller MB, Gonzales J, Culpepper L, Hales RE: Cost-effectiveness of newer antidepressants compared with tricyclic antidepressants in managed care settings. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:47–58Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Lave JR, Frank RG, Schulberg HC, Kamlet MS: Cost-effectiveness of treatments for major depression in primary care practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:645–651Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Schoenbaum M, Unutzer J, Sherbourne C, Duan N, Rubenstein LV, Miranda J, Meredith LS, Carney MF, Wells K: Cost-effectiveness of practice-initiated quality improvement for depression: results of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001; 286:1325–1330Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Nuijten MJ: Assessment of clinical guidelines for continuation treatment in major depression. Value Health 2001; 4:281–294Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Valenstein M, Vijan S, Zeber JE, Boehm K, Buttar A: The cost-utility of screening for depression in primary care. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134:345–360Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Lehmann D, Medicis J: A pharmacoeconomic model to aid in the allocation of ambulatory clinical pharmacy services. J Clin Pharmacol 1998; 38:783–791Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Whynes D, Neilson A, Walker A, Hardcastle J: Faecal occult blood screening for colorectal cancer: is it cost-effective? Health Econ 1998; 7:21–29Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Sharma S, Brown G, Brown M, Hollands H, Shah G: The cost-effectiveness of grid laser photocoagulation for the treatment of diabetic macular edema: results of a patient-based cost-utility analysis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2000; 11:175–179Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Robert G, Brown J, Garvican L: Cost of quality management and information provision for screening: colorectal cancer screening. J Med Screen 2000; 7:31–34Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Hatziandreu E, Koplan J, Weinstein M, Caspersen C, Warner K: A cost-effectiveness analysis of exercise as a health promotion activity. Am J Public Health 1988; 78:1417–1421Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group: Lifetime benefits and costs of intensive therapy as practiced in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. JAMA 1996; 276:1409–1415; correction, 1997; 278:25Google Scholar

56. Littenberg B, Garber A, Sox HJ: Screening for hypertension. Ann Intern Med 1990; 112:192–202Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Mar J, Rodriguez-Artalejo F: Which is more important for the efficiency of hypertension treatment: hypertension stage, type of drug or therapeutic compliance? J Hypertens 2001; 19:149–155Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Nease RJ, Owens D: A method for estimating the cost-effectiveness of incorporating patient preferences into practice guidelines. Med Decis Making 1994; 14:382–392Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Diabetes Cost-Effectiveness Study Group: The cost-effectiveness of screening for type 2 diabetes. JAMA 1998; 280:1757–1763; correction, 1999; 281:325Google Scholar

60. Pear R: Congress weighs drug comparisons. New York Times, Aug 24, 2003, p 18Google Scholar

61. Stone PW, Teutsch S, Chapman RH, Bell C, Goldie SJ, Neumann PJ: Cost-utility analyses of clinical preventive services: published ratios, 1976–1997. Am J Prev Med 2000; 19:15–23Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62. Pyne JM, Rost KM, Zhang M, Williams DK, Smith J, Fortney J: Cost-effectiveness of a primary care depression intervention. J Gen Intern Med 2003; 18:432–441Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Simon GE, Manning WG, Katzelnick DJ, Pearson SD, Henk HJ, Helstad CS: Cost-effectiveness of systematic depression treatment for high utilizers of general medical care. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:181–187Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Simon GE, Katon WJ, VonKorff M, Unützer J, Lin EHB, Walker EA, Bush T, Rutter C, Ludman E: Cost-effectiveness of a collaborative care program for primary care patients with persistent depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1638–1644Link, Google Scholar

65. Brown MC, Nimmerrichter AA, Guest JF: Cost-effectiveness of mirtazapine compared to amitriptyline and fluoxetine in the treatment of moderate and severe depression in Austria. Eur Psychiatry 1999; 14:230–244Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

66. Doyle JJ, Casciano J, Arikian S, Tarride JE, Gonzalez MA, Casciano R: A multinational pharmacoeconomic evaluation of acute major depressive disorder (MDD): a comparison of cost-effectiveness between venlafaxine, SSRIs and TCAs. Value Health 2001; 4:16–31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67. Morrow TJ: The pharmacoeconomics of venlafaxine in depression. Am J Manag Care 2001; 7(11 suppl):S386-S392Google Scholar

68. Thase ME, Entsuah AR, Rudolph RL: Remission rates during treatment with venlafaxine or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 178:234–241Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

69. Spina E, Scordo MG: Clinically significant drug interactions with antidepressants in the elderly. Drugs Aging 2002; 19:299–320Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

70. Koike AK, Unützer J, Wells KB: Improving the care for depression in patients with comorbid medical illness. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1738–1745; correction, 2003; 160:204Google Scholar

71. Sullivan M, Simon G, Spertus J, Russo J: Depression-related costs in heart failure care. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162:1860–1866Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

72. Bower P, Richards D, Lovell K: The clinical and cost-effectiveness of self-help treatments for anxiety and depressive disorders in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2001; 51:838–845Medline, Google Scholar