Social Anxiety in Outpatients With Schizophrenia: A Relevant Cause of Disability

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Social anxiety is a frequent but often unrecognized feature in schizophrenia and is associated with a severe level of disability. To precisely define the assessment, impact, clinical correlates, and consequences of social anxiety in schizophrenia, the authors conducted a survey of schizophrenia patients and a comparison cohort of patients with social anxiety disorder. METHOD: A consecutively enrolled group of 80 outpatients with DSM-IV schizophrenia and a consecutive comparison group of 27 patients with social anxiety disorder were recruited from an institutional psychiatric practice and assessed with the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms, Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms, Social Adjustment Scale, and the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey. RESULTS: Social anxiety scores of schizophrenia patients with comorbid social anxiety disorder (N=29, 36.3%) did not differ from those of subjects with social anxiety disorder as their primary diagnosis. Schizophrenia patients without social anxiety disorder had significantly lower total scores on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale and lower social and performance anxiety subscale scores than did the other two groups. No differences in negative and positive symptom rates were found between schizophrenia patients with and without social anxiety disorder. Schizophrenia patients with social anxiety disorder had a higher lifetime rate of suicide attempts, greater lethality of suicide attempts, more past substance/alcohol abuse disorder, lower social adjustment, and lower overall quality of life. CONCLUSIONS: Social anxiety is a highly prevalent, disabling condition in outpatients with schizophrenia that is unrelated to clinical psychotic symptoms. The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale appeared adequate and reliable in assessing social anxiety disorder in patients with schizophrenia. If these data are confirmed, this study will make a contribution to the search for operational guidelines and adequate next-step treatments for social anxiety disorder in schizophrenia patients.

Although epidemiological studies report a high prevalence of anxiety disorders in schizophrenia, their clinical relevance is still underrecognized. The presence of anxiety in schizophrenia patients has been associated with a greater risk of suicide (1), poorer social functioning, and an increased risk of relapse (2). Bayle et al. (3) reported that 47.5% of schizophrenia patients had a lifetime history of panic attacks, that in 31.2% of cases the onset of panic disorder preceded the onset of schizophrenia, and that the treatment of panic disorder improved clinical and social outcome.

While comorbid panic (3) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (4) have been investigated in schizophrenia patients, social anxiety in schizophrenia has received much less clinical attention. In fact, comorbid anxiety disorders are reported in more than 50% of schizophrenia patients, and in epidemiological studies, the rate of social anxiety disorder ranges from 13% to 39% (5–8). In a 90-day follow-up study, Blanchard et al. (2) found that social anxiety disorder in schizophrenia was a stable phenomenon across assessments. However, it often remains unrecognized and therefore untreated because of its frequent confusion with negative symptoms in schizophrenia patients. This psychopathological debate was first discussed 40 years ago by Meehl in both his original (9) and revised (10) theories. He pointed out that anhedonia, a core negative symptom, could contribute to or be a consequence of what he described as “aversive drift” in schizophrenia, i.e., the tendency to take on a burdensome, threatening, gloomy, negative emotional charge (10). He suggested that this aversive drift is intense and pervasive in the interpersonal domain, manifesting itself as ambivalence and interpersonal fear (9).

People with social anxiety suffer considerable impairment in daily life activities, occupational role, and social relationships (11). Social anxiety is itself a disabling disorder, and individuals with social anxiety disorder as a comorbid condition have a more severe level of disability (12). Subjects with social anxiety disorder have a higher risk of developing substance/alcohol abuse or dependence, and in patients with schizophrenia, as in the general population, substance abuse or dependence appears to be associated with higher impulsivity and suicidality (13). Social anxiety disorder also contributes significantly to decreased quality of life in schizophrenia (14). Therefore, the assessment and treatment of social anxiety disorder comorbidity in schizophrenia patients should improve both clinical and social outcomes.

Penn et al. (15) described the phenomenon of social anxiety in schizophrenia through a role-playing assessment and proposed an instrument (the Ward Fear Scale) for social anxiety disorder in schizophrenia inpatients. To our knowledge, no attempt to assess social anxiety symptoms in schizophrenia outpatients has been made until now. We attempted to precisely define the assessment, clinical correlates, impact, and consequences of comorbid social anxiety disorder in schizophrenia. We studied a consecutively enrolled group of schizophrenia outpatients and a comparison group of patients with social anxiety disorder as their primary diagnosis. Our hypotheses were that schizophrenia patients with social anxiety disorder, compared with schizophrenia patients without social anxiety disorder, would have 1) a higher prevalence of other comorbid anxiety disorders, 2) a greater number of suicide attempts in their history and attempts of greater lethality, and 3) lower social adjustment and quality of life. Moreover, we hypothesized that the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale for social anxiety symptoms would reveal a similar profile for social anxiety disorder patients and schizophrenia patients with social anxiety disorder.

Method

Eighty outpatients diagnosed with schizophrenia according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV and 27 outpatients with a current primary diagnosis of social anxiety disorder were recruited consecutively at the Institute of Neurosciences during the period between December 2000 and November 2002. All the schizophrenia subjects were recruited from the outpatient unit of the institute. During the recruitment period, six subjects with schizophrenia and one patient with social anxiety disorder refused to be interviewed and to enter the study. These subjects have not been considered in the statistical analyses. All the recruited patients, after providing written informed consent, were evaluated for clinical symptoms, demographics, social adjustment, and quality of life. At the time of evaluation, all schizophrenia patients were receiving antipsychotic treatment (clozapine: N=19; olanzapine: N=21; risperidone: N=18; quetiapine: N=14; typical neuroleptics: N=8). Forty-one of the schizophrenia patients were women, 39 were men. They ranged in age from 19 to 45 years (mean=29.0, SD=5.9). Fifteen of the social anxiety disorder patients were women, and 12 were men. They ranged in age from 18 to 56 years (mean=33.4, SD=7.8).

The schizophrenia and social anxiety disorder patients were interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (16) and the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (17). Schizophrenia patients were also assessed with the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (18), the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (18), and the Social Adjustment Scale (19).

Suicide behavior was explored during the clinical interview with the subjects by asking whether they had ever attempted suicide and, if so, how often. A suicide attempt was defined as a self-destructive act carried out with the intention of ending one’s life. Ratings were based not only on the patient’s report but also on all available sources of information, including case notes and interviews with relatives and case managers.

The number of lifetime suicide attempts was ascertained, and the lethality of the suicide attempt was scored from 1 to 4 according to the medical/psychiatric treatment chosen by the clinicians to resolve the episode: 1=discharge from the emergency department without treatment; 2=psychiatric treatment recommended after discharge from emergency department; 3=psychiatric admission; 4=medical admission, including admission to the intensive care unit.

Quality of life was assessed with the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (20), which includes eight multi-item scales. The physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, and general health scales contribute to the composite physical health summary measure, while the vitality, mental health, role-emotional, and social functioning scales contribute to the mental health summary score. The raw scores on the eight Short-Form Health Survey scales range from 0 (worst possible health status as measured by the questionnaire) to 100 (best possible health status). The summary measures are scored by using norm-based methods for the general Italian population (21) and standardized to have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10.

Social anxiety disorder patients were given the evaluations immediately before the beginning of treatment for their disorder.

The two patient groups were compared by analysis of variance (alpha=0.05) and chi-square analyses. Interrater reliability was verified by a series of independent interviews conducted by the authors (S.P. and L.Q.); reliability for both the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale and the Social Adjustment Scale achieved interclass correlation values ranging from 0.80 to 0.92.

Results

Anxiety Disorder Comorbidity

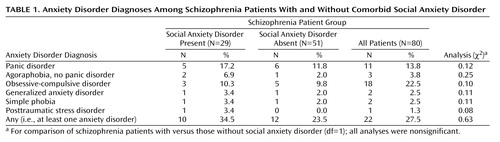

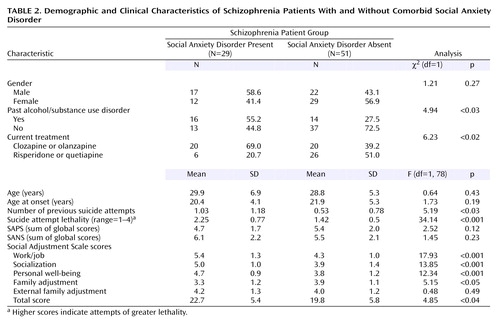

Forty-one (51.3%) schizophrenia patients had at least one anxiety disorder. Social anxiety disorder was diagnosed in 29 (36.3%) schizophrenia patients. Table 1 shows the prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorders, while Table 2 compares schizophrenia patients with and without social anxiety disorder with regard to demographic and clinical data. The subgroup of patients with schizophrenia and comorbid social anxiety disorder did not differ from those without social anxiety disorder in age, age at onset, or gender. The subgroup with schizophrenia plus social anxiety disorder had a significantly higher total number of suicide attempts, suicide attempts of greater lethality, and a higher ratio of past alcohol or substance abuse/dependence. Furthermore, patients with schizophrenia and comorbid social anxiety disorder were significantly more likely to receive clozapine or olanzapine treatment than those without social anxiety disorder, who were significantly more likely to receive risperidone or quetiapine treatment (Table 2).

The patients with schizophrenia and social anxiety disorder had significantly worse social adjustment as measured with the Social Adjustment Scale (Table 2). In particular, three of five areas of adjustment were significantly worse in patients with schizophrenia plus social anxiety disorder: work/job, socialization, and personal well-being. Patients with schizophrenia plus social anxiety disorder reported a higher family adjustment, and no difference was found in external family adjustment.

Comparison of Social Anxiety Severity

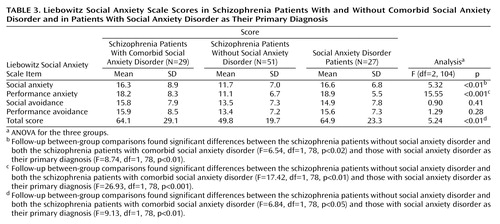

Relative to schizophrenia patients without social anxiety disorder, schizophrenia patients with comorbid social anxiety disorder had a significantly higher mean total score on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (Table 3) and a significantly higher score for total anxiety (mean=33.7 [SD=15.9] versus 22.8 [SD=7.54]) (F=17.27, df=1, 78, p<0.001) as well as a nonsignificantly higher score for total avoidance (mean=30.5 [SD=14.4] versus 26.9 [SD=14.49]). Both the performance anxiety and social anxiety scores appeared significantly higher in patients with schizophrenia plus social anxiety disorder than in those without social anxiety disorder, whereas no differences emerged for performance avoidance and social avoidance scores (Table 3). No differences were found between the two subgroups on the SAPS and SANS sum of global scores.

No significant differences were found between schizophrenia subjects with social anxiety disorder and subjects with social anxiety disorder as their primary diagnosis in total score on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale or the anxiety and avoidance scores (Table 3). As seen with the schizophrenia patients with comorbid social anxiety disorder, subjects with social anxiety disorder as their primary diagnosis had significantly higher total scores on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale than the schizophrenia patients without social anxiety disorder as well as significantly higher social anxiety and performance anxiety scores; there were no differences between the two groups in social avoidance and performance avoidance scores.

Quality of Life

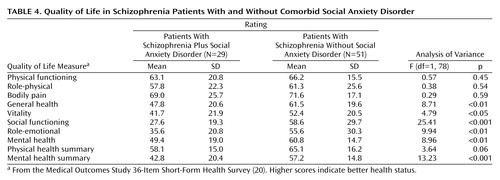

Mean scores obtained from the Short-Form Health Survey are displayed in Table 4. Significant differences in several areas of quality of life were found between schizophrenia patients with and without comorbid social anxiety disorder. In particular, schizophrenia patients with comorbid social anxiety disorder reported significantly lower levels of quality of life in the areas of general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health. They also had a significantly lower score on the “mental health summary” composite scale.

Discussion

Consistent with other studies, we found that 36.3% of schizophrenia patients have a comorbid social anxiety disorder. Our findings also showed that in our group of schizophrenia patients receiving medical treatment, social anxiety disorder is by far the most common anxiety disorder. Cosoff and Hafner (6) also found social anxiety disorder to be the most prevalent anxiety disorder in schizophrenia patients, but the rate that they found was about 17%. This difference of prevalence could be due to differences in subject recruitment: Cosoff and Hafner’s study was conducted in the open wards of an acute adult service, while all our subjects were in outpatient treatment.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to investigate social anxiety in outpatients with schizophrenia. All the schizophrenia subjects were recruited from the outpatient unit of the institute and were in a clinical remission or partial remission phase at the time of the assessment, as documented by the average low positive and negative symptom scale scores. It is noteworthy that social anxiety symptoms become evident when patients are in a phase free from schizophrenia symptoms; the former are a reflection of the patients’ greater efforts at social adaptation and increased expectations.

Our study was primarily a clinical and not an epidemiological investigation, and it involved clinical detection and assessment. This could enhance the accuracy of the assessment and could explain the prevalence of social anxiety disorder found in our group of schizophrenia patients.

The use of the Liebowitz scale for assessment of social anxiety seems adequate and reliable. No differences were found on any single item score between schizophrenia patients with social anxiety disorder and patients with social anxiety disorder as a primary diagnosis. In other words, no differences resulted in social anxiety phenomenology when it appears as a primary diagnosis or when comorbid with schizophrenia. The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale could also reliably distinguish these groups from schizophrenia patients without comorbid social anxiety disorder. It seems that social anxiety in patients with schizophrenia, related or unrelated to treatment, has a similar clinical profile to that experienced by social anxiety disorder patients without schizophrenia. In any case, it seems that the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale can be regarded as a reliable instrument to assess social anxiety in schizophrenia outpatients, in a similar way to the scale devised by Penn et al. (15) to measure social anxiety in inpatients.

In some preliminary assessments conducted with schizophrenia subjects before the beginning of the study, we found that the administration of the scale by a clinician ensures greater reliability than with self-administration. In particular, we found that the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale, SANS, and SAPS should be administered by the same clinician in order to avoid possible ambiguity between social anxiety symptoms and positive and negative symptoms. We observed a similar rate of positive and negative symptoms in both groups of schizophrenia patients, those with and without comorbid social anxiety disorder.

In the first attempt at a systematic study of social anxiety in schizophrenia, Penn et al. (15) found that negative symptoms were related to observational ratings of anxiety during role playing, while positive symptoms were not. Undoubtedly, the experience of paranoia and the social withdrawal found in schizophrenia can mimic social anxiety disorder symptoms. Clinical attention needs to focus on the presence of anxiety symptoms associated with avoidance behavior and on the level of insight, both of which are reduced when negative symptoms are predominant in the clinical picture. In schizophrenia, withdrawal behavior linked to negative symptoms is phenomenologically sustained by detachment, while social anxiety is related to interpersonal sensitivity. On the basis of our observation, a patient typology profile of the following kind could emerge: good familiar adaptation; low positive and negative symptom scores; difficulties relating to specific key social situations like those investigated by the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale, i.e., not related to paranoid experience but to stress-elicited anxiety. Although the distinction between social anxiety disorder and negative/positive symptom-related behavior remains somewhat difficult, clinical experience shows that this clinical distinction is easier in schizophrenia patients than in patients with social anxiety disorder as their primary diagnosis.

One limitation of the investigation was that the social anxiety and the schizophrenia groups differed with regard to whether or not they were receiving medication at the time of assessment. May this have confounded the results in some way? It cannot be excluded that social anxiety in schizophrenia subjects could be related to treatment, in accordance with findings described by our group in a previous study of 12 schizophrenia subjects where social anxiety disorder was induced by clozapine treatment (22, 23). It is also possible that antipsychotic treatments, particularly clozapine and olanzapine, contribute to make the prevalence of social anxiety disorder in our group higher than that reported by Cosoff and Hafner (6).

Previous anamnestic examination of the clinical reasons why an atypical neuroleptic treatment was chosen for each single patient revealed that in no case was the choice based on the fact that the individual exhibited anxiety. However, in this study, the potential effect of treatment (1084 mg in chlorpromazine equivalents) and the association between atypical antipsychotics and social anxiety symptoms have still to be defined, since the therapy was chosen and not randomly assigned, and neuroleptic treatments with significant extrapyramidal side effects could contribute to confound the differential diagnosis between negative symptoms and social anxiety-related behaviors. Our results are in line with those of Stern et al. (24), who found that social anxiety disorder symptoms are common, quite severe, and not correlated with psychotic symptom severity among schizophrenia outpatients. In our previous study of 12 schizophrenia subjects with social anxiety disorder induced by clozapine treatment (22, 23), we also found that fluoxetine augmentation improved social anxiety symptoms but not negative and positive symptoms.

Schizophrenia subjects with comorbid social anxiety disorder showed indexes of lower social adjustment and lower quality of life compared with patients without social anxiety disorder. This was expected, taking into account that social anxiety, especially when present as a comorbid condition, causes substantial impairment in quality of life, lower work productivity and earnings, and greater utilization of health services (25). The finding of a higher total number of suicide attempts and greater lethality of suicide attempts in patients with schizophrenia plus social anxiety disorder is also in line with the risk associated with social anxiety. Schneier et al. (26) reported no increase in suicide risk among “uncomplicated social anxiety” (0.1%, N=11 of 9,953) and a higher rate among those with “complicated social anxiety” (15.7%, N=39 of 249). Katzelnick et al. (25) found that suicide was attempted by 21.9% of subjects with noncomorbid generalized social anxiety disorder, a rate that is similar to that for current major depression. At the same time patients with schizophrenia plus social anxiety disorder had a higher rate of past alcohol or substance abuse/dependence.

In summary, social anxiety disorder is a common comorbid condition in schizophrenia, and it should be suspected in socially impaired subjects. Furthermore, its presence implies the need for both psychological and pharmacological therapeutic specificity and often a comprehensive treatment approach. Recently, Halperin et al. (14) studied the efficacy of an 8-week, group-based cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety in subjects with schizophrenia; they found clinically significant improvements in quality of life, social anxiety, and social phobia symptoms in the majority of treated patients. On the other hand, atypical neuroleptic treatments may accentuate the risk of the emergence of disorders like social anxiety (but also obsessive-compulsive disorder and panic symptoms); particular care is therefore required, especially when prescribing compounds like clozapine or olanzapine to schizophrenia patients.

If these observations are confirmed by further studies in larger samples, adequate next-step treatments will need to be sought. Currently there are no operational guidelines for the treatment of comorbid social anxiety disorder in schizophrenia. Fluoxetine augmentation of neuroleptic treatment has been shown to be effective in a previous study by our group (23), but trials in larger samples are needed. No data are available for other possible options for schizophrenia patients with social anxiety disorder, such as a dose reduction in atypical neuroleptic treatment or the switch to another neuroleptic compound. At the same time, psychological intervention has been indicated as a possible effective strategy in a study on 20 subjects (14). This observation needs to be confirmed.

|

|

|

|

Received Feb. 5, 2003; revision received July 3, 2003; accepted July 10, 2003. From the Department of Neurological and Psychiatric Sciences, University of Florence, Florence, Italy; Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York; and the Institute of Neurosciences, Florence, Italy. Address reprint requests to Dr. Pallanti, Istituto di Neuroscienze, Viale Ugo Bassi 1, 50137 Florence, Italy; [email protected] (e-mail).

1. Taiminen T, Huttunen J, Heila H, Henriksson M, Isometsa E, Kahkonen J, Tuominen K, Lonnqvist J, Addington D, Helenius H: The Schizophrenia Suicide Risk Scale (SSRS): development and initial validation. Schizophr Res 2001; 47:199–213Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Blanchard JJ, Mueser KT, Bellack AS: Anhedonia, positive and negative affect, and social functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1998; 24:413–424Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Bayle FJ, Krebs MO, Epelbaum C, Levy D, Hardy P: Clinical features of panic attacks in schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry 2001; 16:349–353Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Eisen JL, Beer DA, Pato MT, Venditto TA, Rasmussen SA: Obsessive-compulsive disorder in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:271–273Link, Google Scholar

5. Kendler KS, McGuire M, Gruenberg AM, Walsh D: Examining the validity of DSM-III-R schizoaffective disorder and its putative subtypes in the Roscommon Family Study. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:755–764Link, Google Scholar

6. Cosoff SJ, Hafner RJ: The prevalence of comorbid anxiety in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1998, 32:67–72Google Scholar

7. Cassano GB, Pini S, Saettoni M, Dell’Osso L: Multiple anxiety disorder comorbidity in patients with mood spectrum disorders with psychotic features. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:474–476Link, Google Scholar

8. Bermanzohn PC, Porto L, Arlow PB, Pollack S, Stronger R, Siris SG: Hierarchical diagnosis in chronic schizophrenia: a clinical study of co-occurring syndromes. Schizophr Bull 2000; 26:517–525Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Meehl PE: Schizotaxia, schizotypy, schizophrenia. Am Psychol 1962; 17:827–838Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Meehl PE: Toward an integrated theory of schizotaxia, schizotypy and schizophrenia. J Personal Disord 1990; 4:1–99Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Wittchen HU, Fuetsch M, Sonntag H, Muller N, Liebowitz M: Disability and quality of life in pure and comorbid social phobia—findings from a controlled study. Eur Psychiatry 1999; 14:118–131Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Wittchen HU, Fehm L: Epidemiology, patterns of comorbidity, and associated disabilities of social phobia. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2001; 24:617–641Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Gut-Fayand A, Dervaux A, Olie JP, Loo H, Poirier MF, Krebs MO: Substance abuse and suicidality in schizophrenia: a common risk factor linked to impulsivity. Psychiatry Res 2001; 102:65–72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Halperin S, Nathan P, Drummond P, Castle D: A cognitive-behavioural, group-based intervention for social anxiety in schizophrenia. Austr NZ J Psychiatry 2000; 34:809–813Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Penn DL, Hope DA, Spaulding W, Kucera J: Social anxiety in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1994; 11:277–284Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID), Clinician Version. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1996Google Scholar

17. Liebowitz MR: Social phobia, in Modern Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry: Anxiety. Edited by Klein DF. Basel, Switzerland, Karger, 1987, pp 141–173Google Scholar

18. Andreasen NC: Schizofrenia: Scale per la valutazione dei Sintomi Positivi e Negativi. Edited by Moscarelli M, Maffei C. Milan, Italy, Cortina, 1987Google Scholar

19. Schooler N, Hogarty GE, Weissman MM: Social Adjustment Scale II (SAS-II), in Resource Materials for Community Mental Health Program Evaluators. Edited by Hargreaves WA, Attkisson CC, Sorenson JE. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education and Welfare, 1979, pp 290–330Google Scholar

20. Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosisnki M, Gandek B: SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, Health Institute, 1993Google Scholar

21. Apolone G, Mosconi P: The Italian SF-36 health survey: translation, validation and norming. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51:1025–1036Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Pallanti S, Quercioli L, Pazzagli A: Social anxiety and premorbid personality in paranoid schizophrenic patients treated with clozapine. CNS Spectr 2000; 9:29–43Google Scholar

23. Pallanti S, Quercioli L, Rossi A, Pazzagli A: The emergence of social phobia during clozapine treatment and its response to fluoxetine augmentation. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:819–823Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Stern RG, Meiraj H, Ballou S: High social phobia scale scores in schizophrenia do not correlate with psychosis symptom severity scores, in 1999 Annual Meeting New Research Program and Abstracts. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1999, p 66Google Scholar

25. Katzelnick DJ, Kobak KA, DeLeire T, Henk HJ, Greist JH, Davidson JRT, Schneier FR, Stein MB, Helstad CP: Impact of generalized social anxiety disorder in managed care. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1999–2007Link, Google Scholar

26. Schneier FR, Johnson J, Hornig CD, Liebowitz MR, Weissman MM: Comorbidity and morbidity in an epidemiologic sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:282–288Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar