Acute Porphyrias: A Case Report and Review

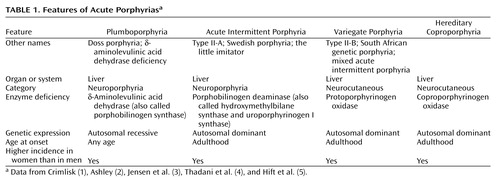

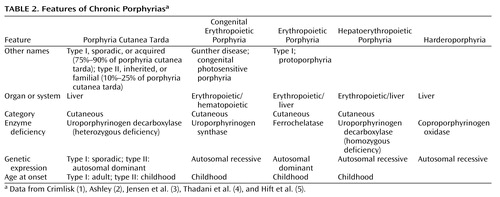

As befits a hematologic class of disorders, the word “porphyria” derives from the Greek word porphuros, which means red or purple (1). The porphyrias (Table 1 and Table 2) are a group of rare metabolic disorders arising from reduced activity of any of the enzymes in the heme biosynthetic pathway. The disorders may be either acquired (for instance, through a toxin acting on one of the enzymes) or inherited through a genetic defect in a gene encoding these enzymes. These deficiencies disrupt normal heme production, with symptoms especially prominent when increased heme is required. Porphyrin precursors, overproduced in response to synthetic pathway blockages, accumulate in the body (1–31), cause diverse pathologic changes, and become the basis for diagnostic tests.

In this review we focus on the two neuroporphyrias (acute intermittent porphyria and plumboporphyria) and the two neurocutaneous porphyrias (hereditary coproporphyria and variegate porphyria). These four entities, of all the porphyrias, are the only ones with neuropsychiatric manifestations. We use a case of variegate porphyria to illustrate how the manifestations may be broad, the relevance in neuropsychiatric disorders overlooked, and the diagnosis unsuspected. Given the variable and nonspecific clinical features, we emphasize the need to carefully interpret excretion patterns and concentrations of porphyrin precursors in urine and stool to make a specific diagnosis. The workup of any potential case needs to be individualized, taking into consideration both the history and the symptoms at the time of evaluation. We discuss the complexities of making a diagnosis of porphyria. Without carefully gathering a history and having a clear understanding of what laboratory tests can and cannot show, making the diagnosis will be delayed, possibly resulting in increased morbidity and use of medical and financial resources. When evaluating complicated neuropsychiatric cases of uncertain cause, we advocate maintaining a high degree of awareness for porphyria.

Case Presentation

Mr. A, a 47-year-old, married, male florist with no significant previous medical or psychiatric history, presented to a local neurologist with a 3-month history of symptoms of apparent neurologic origin. He had had progressive loss of memory and concentration, spells of confusion, and indeterminate jerking spasms of the upper extremities and facial muscles that lasted only seconds but occurred up to 30 times per day. The neurologic examination was normal; the neurologist did not make a specific diagnosis but did prescribe nefazodone, an antidepressant.

A few weeks later, psychiatric symptoms developed that were serious enough to warrant admission to a local hospital. Mr. A had paranoid delusions and auditory hallucinations. He heard animals in his room and thought the police wanted to harm him. He had hyponatremia, so before his transfer to the psychiatric ward, an internist evaluated him but offered no specific explanation for the hyponatremia. A psychiatric mood disorder was diagnosed, and Mr. A was prescribed sertraline, valproic acid, and perphenazine and dismissed after 5 days. Four days later, he was rehospitalized, still psychotic and hyponatremic. This time the hyponatremia was attributed to psychogenic polydipsia. Venlafaxine was substituted for sertraline, and his dismissal instructions recommended gradually discontinuing valproic acid and perphenazine.

Mr. A continued to display a peculiar mixture of neurologic, psychiatric, and medical symptoms. Spells of confusion and jerking spasms became longer and more frequent. Hyponatremia recurred several times, and his cognitive abilities worsened. Personality changes developed along with mood lability, intermittent suicidal ideation, and behavioral dyscontrol. At times he withdrew to his home, exhibiting anhedonia and psychomotor slowness. At other times he acted indecisive, irritable, physically agitated, and verbally aggressive. He showed disinhibited and inappropriate behavior (such as talking to strangers). He continued to have frequent ego-dystonic, increasingly complex, delusional attacks, although they lasted only minutes. He thought the police were after him for stealing from his workplace, and he declared in the absence of any evidence that he had been associating with prostitutes, both male and female, and that his wife had been trying to steal his money. The formerly isolated physical finding of hyponatremia was now accompanied by increased thirst and urination, nausea, fluctuating weight, occasional dizziness, shortness of breath, dysphagia, and decreased sexual drive and performance. Even so, his treating physicians continued to regard his entire syndrome as emanating from a functional psychiatric disorder.

Five months into his illness, during an amnestic spell, Mr. A had a car accident. His family wondered whether the accident represented an attempt at suicide. Again, he was admitted to a psychiatry service, the venlafaxine regimen was changed back to sertraline, and olanzapine was added. A month later he was hospitalized again for recurrence of hyponatremia.

Seven months after his initial presentation, Mr. A was referred to our institution’s outpatient neurology clinic. Although results of the neurologic examination were again normal, the neurologists thought that something was wrong. The quest for an explanation led to multiple hospitalizations on various services, including the inpatient epilepsy unit for extended video-EEG monitoring, the psychiatry unit for the Intensive Outpatient Program, and both inpatient neurology and inpatient psychiatry services. Subspecialists who offered opinions included behavioral neurologists, pulmonologists, endocrinologists, hematologists, geneticists, general internists, and psychologists. Numerous esoteric diagnoses were entertained, multiple procedures and tests ordered, and diverse medications prescribed without effect. Throughout this exhaustive evaluation, a functional psychiatric disorder continued to be considered the most likely explanation for Mr. A’s problem.

Although he scored 30 of 30 on the Folstein Mini-Mental Status Examination, Mr. A showed marked psychomotor slowness. More formal neurocognitive testing proved challenging, hindered by his spells and slowness. A neuropsychologist was able to determine, however, that the patient’s present cognitive status was lower than expected on the basis of his education and employment and that he had unexplained low scores for confrontational naming, semantic fluency, learning and memory skills, and the Adult Verbal Learning Test.

Later in Mr. A’s evaluation, an autoimmune disorder was suspected (results were positive for antinuclear antibody at 1:40 and for IgG phospholipid antibody at 1:64), but a 4-week trial of prednisone therapy that was instituted did not result in improvement. Although intriguing, nonspecific cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings and an EEG tracing abnormality did not suggest a particular diagnosis. Prolonged video-EEG monitoring showed neither EEG discharge abnormalities nor changes in consciousness during multiple behavioral spells that were videotaped. A rapid progressive frontotemporal degenerative process, as well as Kuf’s disease and acute porphyria, were considered. Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), electromyography (EMG), and 24-hour collection for urine and stool porphyrins were performed. Brain biopsy was contemplated but not performed. The SPECT scan showed abnormal cerebral cortical perfusion with moderate patchy reduction of flow in the temporal and postparietal lobes and more severe reduction in the superior occipital regions. EMG showed mildly slowed conduction velocities, suggestive of a mild, chronic, slowly progressive, dependent peripheral neuropathy.

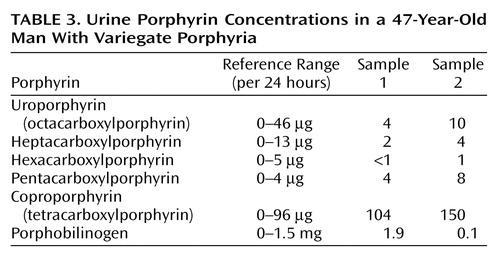

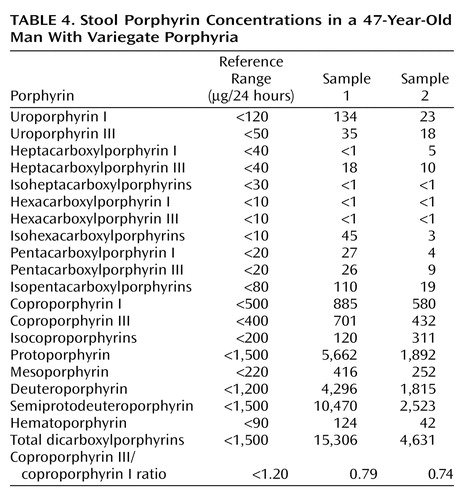

Finally, whereas concentrations of urine porphyrins in Mr. A were not suggestive of an acute porphyric attack (Table 3), increased stool porphyrin concentrations were consistent with mild expression of variegate porphyria (Table 4).

For Mr. A, acute porphyria was the only diagnosis that could encompass the protean clinical picture. A hematologist and a geneticist took over the patient’s care. The patient’s ineffective psychiatric medications were discontinued. Both patient and family were given supportive therapy and counseling about measures to prevent acute attacks, including proper diet and hydration and potential precipitants of acute attacks.

A specific precipitating factor was not identified for Mr. A, but we noted that his illness had emerged during a period of extreme job stress, complicated by excessive smoking and caffeine intake. We advised his not returning to work at the florist shop because of the pressure. We warned him that smoking 2 to 3 packs of cigarettes and drinking 8 to 10 cups of coffee per day could exacerbate his symptoms. We considered the possibility that chemicals used in the floral shop could be adding to his troubles, although this seemed unlikely, given his several years of working in the shop.

Genetic testing was considered in order to confirm the diagnosis, but a search for a laboratory that would analyze the samples was unsuccessful. Family counseling, including genetic counseling, was provided to this patient and his two children. Because variegate porphyria is autosomal dominant, a 50% possibility exists for the genetic defect to occur in Mr. A’s offspring (6). In the absence of symptoms in the children, however, porphyrin testing was not recommended because even if the offspring had inherited the defect, the chance of overt expression was low.

After dismissal from our medical center, Mr. A and his wife were bitter and angry about the emotional and financial strains of the disease. Therefore, they refused follow-up evaluation or further testing.

Discussion

Why are the porphyrias difficult to understand? Why is the literature about this illness confusing? First, each porphyria has been known by several names or classified from various perspectives (on the basis of the initial presentation, where the defective synthesis site is, or what the clinical manifestations are). Second, the defective enzyme may have been given more than one name (Table 1 and Table 2). Third, experts disagree about when to suspect acute porphyria, what to do to diagnose it, and how to interpret the results of diagnostic tests.

General Background

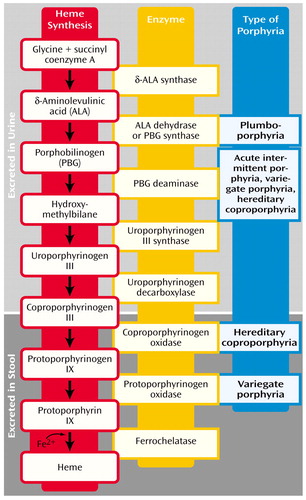

A specific enzyme catalyzes each step of the heme biosynthetic pathway (Figure 1). Eight enzymes are involved in the synthesis of heme and, except for the first enzyme (δ-aminolevulinate synthase), low activity of any of these can disrupt the normal pathway, especially when a stimulus occurs to increase heme production. The suboptimal activity of any one of these seven enzymes, because of either a defective gene or a toxic chemical effect, results in the overproduction and accumulation of the preceding intermediates, known as porphyrins or porphyrin precursors (1–31). Although these intermediates have no known useful physiologic function, they act as highly reactive oxidants (3, 31), and deficiencies of the seven enzymes are linked to specific types of porphyria (3, 4, 29, 31).

The term “acute porphyrias” subsumes both neuroporphyrias (acute intermittent porphyria and plumboporphyria) and neurocutaneous porphyrias (hereditary coproporphyria and variegate porphyria) (1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 19, 21, 33). Although all subtypes are rare, acute intermittent porphyria is the most common (1, 4, 5, 7, 20, 21, 31, 34–36). All four are characterized by recurrent acute attacks (1, 4, 6, 7), and their clinical manifestations are variable (1, 4, 34, 37). Symptoms may vary considerably in the same patient during different episodes, as well as among patients with the same porphyria subtype. Because the clinical course can vary from acute, self-limiting attacks to attacks that result in chronic or progressive deficits (1, 37), the attacks may mimic many other psychiatric or medical disorders, making the potential for misdiagnosis great (1, 4, 16, 34, 35, 37, 38).

The four acute porphyrias are clinically indistinguishable during acute attacks (1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 15, 17, 34, 39–42), particularly because patients with variegate porphyria and hereditary coproporphyria may not exhibit dermatologic changes (1, 4, 6, 7, 34, 37, 40, 43). Skin lesions accompany acute attacks in about one-half of the patients with variegate porphyria and in about one-third of the patients with hereditary coproporphyria (4, 40, 42). The variability of the clinical course, the lack of understanding of an appropriate diagnostic process, and the lack of a universally accepted standard for test result interpretation add to the difficulty of making a diagnosis (1, 37).

Clinical Manifestations

Reported clinical manifestations of acute porphyria include neuropsychiatric symptoms and clinical signs (hysteria, anxiety, depression, phobias, psychosis, agitation, delirium, restlessness, seizures, neuropathy, sensory involvement, and hyporeflexia), autonomic instability (hypertension, tachycardia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and constipation), dehydration and electrolyte imbalance (hyponatremia, hypokalemia, and hypocalcemia), and dermatologic features (photosensitivity, skin fragility, hypertrichosis, and hyperpigmentation) (1–8, 10, 11, 15, 18, 20, 22, 28–31, 34–36, 38, 39, 43–50).

Abdominal pain, peripheral neuropathy, and changes in mental status are the classic triad of an acute attack (37). Severe abdominal pain is the most commonly reported presenting symptom during acute attacks (4, 7, 8, 18, 31, 34, 51). A clinical presentation without abdominal pain is unusual in acute porphyria, and some authors suggest that initial screening tests should be limited to patients with this symptom (14, 52). However, such a criterion would have excluded our patient. Thus, we contend that the best approach is to make a careful, individualized assessment rather than to rely on dogmatic restrictions about which patients can be considered to have the disorder.

The peripheral neuropathy tends to be progressive and involves motor and sensory nerves. Muscular weakness can progress to quadriparesis and respiratory paralysis and arrest, which may resemble Guillain-Barré syndrome. Unlike in Guillain-Barré syndrome, however, results of CSF analysis in acute porphyria are usually normal (1, 3–6, 15, 22, 34, 39), as was the case in multiple CSF analyses for our patient.

Among patients with acute porphyria, 20%–58% have neuropsychiatric symptoms during acute exacerbations (34, 35, 37). Neuropsychiatric symptoms were predominant in our patient’s clinical presentation. The pathogenesis of the neuropsychiatric manifestations remains unclear and poorly understood (1, 4, 5, 16, 29, 31, 39, 44, 45), but multiple hypotheses have been proposed, including CNS metabolic abnormalities, ischemia, demyelination, oxidative stress, free radical damage (30), aminolevulinic acid direct neurotoxicity, and nervous tissue heme deficiency (1, 3, 4, 29, 31, 39, 44, 45). Postmortem CNS pathologic findings have not correlated with antemortem clinical features (1, 39, 45). One group of authors claimed that psychiatric disturbances and confusion are not a significant part of the acute attack; they cite no specific data to support their claim, however (5).

Our patient presented repeatedly with hyponatremia. Marked hyponatremia frequently complicates acute porphyrias (4, 5, 7, 31, 34, 45). Its mechanism is not fully understood, but the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (4, 7, 34, 45), with resultant dehydration (3, 4), nephrotoxicity (4), excess renal sodium excretion, and damage to the supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus, has been implicated in its pathogenesis (7). Hyponatremia may precipitate convulsions (5), but epilepsy is rarely the only presenting symptom of acute porphyria. One study reported that hyponatremia more often occurs with appropriate antidiuretic hormone levels (3).

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of acute porphyria is complicated and probably faulty because of its rarity. In general, the prevalence of porphyria varies from country to country, as do the types of porphyria (1, 4, 34, 35). Because the disease has variable expression, the estimated prevalence of gene carriers for acute intermittent porphyria in the general population of the United States is 1–2 per 10,000 people, with clinical disease manifesting in approximately 10% of these carriers (1, 7, 31, 34, 35, 37).

Some authors report that acute porphyria is more common in patients with psychiatric illness than in the general population (7, 34, 37, 45). This is not surprising because of the similar phenotypic presentations of general psychiatric illness and porphyria, as was the case with our patient. These authors evaluated patients who had psychiatric diagnoses (most with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or atypical psychosis with neuropsychiatric impairment) and reported a point prevalence for acute intermittent porphyria between 0.21% and 0.48% (1, 34). These estimates seem to represent an increased prevalence in both latent and manifest porphyria in psychiatric populations, although comparison groups are lacking. A limitation of earlier studies of both healthy and psychiatric populations is that they used only one test, the Watson-Schwartz test, which is now known to have low sensitivity (1, 42), thus underestimating the prevalence of this disorder.

Recovery of mental function often lags behind physical recovery, and some patients report functional disturbances indefinitely (3). This seems to have been the case in our patient, whose functional symptoms persisted.

Workup and Diagnosis

Most routine investigations may offer information but are not helpful in making a diagnosis, including a diagnosis of porphyria (1). For example, with our patient, abnormal EMG findings; nonspecific cranial MRI, SPECT, and EEG findings; and recurrent episodes of hyponatremia were not pathognomonic for a particular disorder.

Urine and stool samples were most likely obtained between attacks. The diagnosis of acute porphyria would have been confirmed by repeating the quantitation of urine porphyrin during an acute episode and finding elevated levels (2–5 times normal) of porphobilinogen. However, our patient did not have another acute episode in the hospital.

Diagnostic Algorithm

The biochemical distinction among the porphyrias resides with the measurement of porphyrins and their metabolites in urine and feces (9, 17, 22, 53–55). An algorithm for the diagnosis of porphyrias is based on an understanding of which porphyrin precursors to expect in urine or stool samples when evaluating for acute porphyria (Figure 1). Porphyrin intermediates in the first half of the heme biosynthetic pathway (porphobilinogen, aminolevulinic acid, and uroporphyrin) are water soluble and fat insoluble. Thus, excessive excretions occur in urine, not stool (5, 6). Terminal half porphyrin intermediates (coproporphyrin and protoporphyrin) are fat soluble and excreted through bile in the stool (1, 5, 6, 9). Because coproporphyrin is water soluble as well, it may also be present in the urine (5, 6).

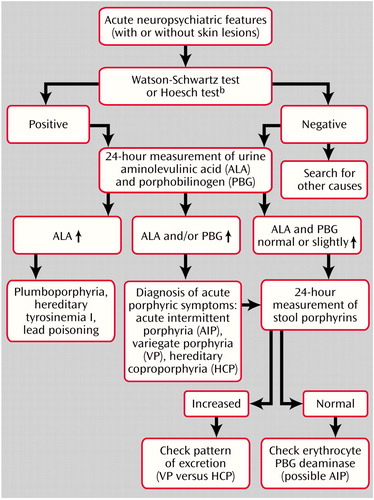

In the acute setting, particularly when symptoms suggest an acute porphyric syndrome, the critical need is to make a diagnosis rapidly (32, 53). The precise type of acute porphyria is of secondary importance, because the basic principles of management of the acute attack are the same, regardless of the specific diagnosis (Figure 2) (32).

Acute attacks for all four acute porphyrias are invariably associated with increased urinary excretion of aminolevulinic acid or porphobilinogen or both (4, 8, 15, 21, 31, 32, 36, 55–57). Therefore, some clinicians use qualitative rapid screening tests for porphobilinogen like the Watson-Schwartz test or the Hoesch test. Results of these tests are positive in most acute attacks, but the tests are unreliable (4, 32, 36, 53). These screening methods have a sensitivity of only 40%–69%, and the sensitivity is even lower (28%–53%) when the urine samples are concentrated. It is now recommended that Watson-Schwartz screening tests be abandoned and, ideally, all urine samples be analyzed by quantitative methods (33, 36, 42, 57). Measuring the 24-hour urinary excretion of porphobilinogen and aminolevulinic acid during a symptomatic period is the most helpful method of determining whether a particular set of symptoms and signs is due to acute porphyria (15).

If levels of urine porphobilinogen or aminolevulinic acid or both are increased, diagnosis of an acute porphyria attack can be made (1, 32, 34, 36, 43). When urine porphobilinogen is elevated more than 2 to 5 times its normal limits, an acute attack of acute intermittent porphyria, variegate porphyria, or hereditary coproporphyria should be suspected (6, 58). During an acute attack, acute intermittent porphyria is distinguished from variegate porphyria or hereditary coproporphyria by normal or near-normal levels of fecal porphyrin (42, 53). Reduced activity of erythrocyte porphobilinogen deaminase further supports the diagnosis of acute intermittent porphyria (4, 5, 53). The rare exception in which urine aminolevulinic acid but not porphobilinogen is increased is plumboporphyria (1, 32, 36), which is characterized by severe deficiency of hepatic 5-aminolevulinic acid dehydrase. Patients with hereditary tyrosinemia (type I tyrosinemia) or lead poisoning may also present with an elevation of only urinary aminolevulinic acid (1, 6, 32).

If levels of urine porphobilinogen and aminolevulinic acid are normal, the physician can be reassured that the patient is not having an acute attack of porphyria. The patient may still have porphyria, however, with symptoms and signs due to another cause (53), or the quantitation may have been performed between attacks (40, 59). If the patient’s clinical history suggests an acute porphyric syndrome, fecal porphyrin subtyping and quantitation can confirm its presence and distinguish among acute intermittent porphyria, variegate porphyria, and hereditary coproporphyria subtypes (4, 40, 42, 53, 60).

Variegate porphyria and hereditary coproporphyria, like acute intermittent porphyria, have decreased porphobilinogen deaminase activity and resultant increased levels of urinary porphobilinogen during acute attacks (1, 5–7, 40, 47). However, variegate porphyria is specifically distinguished by a deficiency of protoporphyrinogen oxidase, which leads to accumulation of both protoporphyrinogen and protoporphyrin in bile and feces (1, 2, 5, 7, 23, 31, 40–42, 47, 53, 61). In variegate porphyria, the preponderant stool porphyrin is protoporphyrin (6, 40, 62), with concentrations ranging from 3 to 7 times the normal value (53). Hereditary coproporphyria also has a distinct stool porphyrin pattern. Defective coproporphyrinogen oxidase leads to accumulation of coproporphyrin in both stool and urine (1, 2, 5–7, 31, 42, 47, 53). In hereditary coproporphyria, the concentration of stool coproporphyrinogen is at least 5 times normal. In our patient, concentrations of urine porphyrins were within normal limits, ruling out an acute attack (Table 1). However, the concentration of his stool protoporphyrin was three times normal, suggesting the diagnosis of variegate porphyria (Table 4).

False negative results of urine porphyrin quantitation may be caused by a time lag between sample collection and testing (13, 35). Since porphyrins are light sensitive, specimens must be stored in the dark and tested as soon as possible. When exposed to normal lighting, urine porphyrin concentration is reduced by 50% in 24 hours (1).

In summary, increased urinary excretion of porphobilinogen or aminolevulinic acid (or both) confirms an acute attack of one of the four acute porphyrias (5–7, 13, 34, 36, 40, 42, 53, 56). Between attacks of the neuroporphyrias (acute intermittent porphyria and plumboporphyria), concentrations of urine porphobilinogen and aminolevulinic acid can remain elevated (53, 56) or decrease below detection limits (1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 13, 42, 56). If the latter occurs, either diagnosis becomes particularly difficult to make because in neuroporphyrias, concentrations of stool porphyrins remain normal both during and between acute attacks (5–7, 13, 53, 56). In the neurocutaneous porphyrias (variegate porphyria and hereditary coproporphyria), the situation is less complicated: levels of urine porphobilinogen and aminolevulinic acid are often normal between attacks, but levels of stool porphyrins are always increased, both during and between attacks (1, 3, 6, 7, 13, 34, 40, 42, 53, 62, 63).

Treatment and Prophylaxis

Management strategies in acute episodes of porphyria are limited, and therapy is mainly supportive (2, 5, 7, 28, 37). Treatment mainstays include identifying and limiting possible precipitants, maintaining adequate intake of carbohydrates and fluids, and administering haem arginate (3–5, 7, 15, 16, 28, 29, 31, 34, 35, 43, 46, 48, 50, 64). Complications of the disease must also be managed with appropriate subspecialty consultation (5–7, 15, 28, 34, 43, 46).

Perturbations in both the external and internal environments are believed to greatly influence acute porphyria expression (2–4, 6, 10, 21, 22, 30). Environmental factors such as prescribed or illicit drugs, chemicals, a low-carbohydrate and low-calorie diet, dehydration, infection, psychologic stress, excessive alcohol intake, cigarette smoking, variations in levels of physiologic hormones (such as during menstrual cycling), sex hormone treatments, and sun exposure may precipitate acute attacks (2–4, 6, 11, 13, 15, 18, 20, 21, 30, 31, 34, 37, 46, 60, 65). Some authors deny the importance of stress, infection, and fasting (1, 5); however, we believe that our patient’s low caloric intake, excessive smoking and caffeine use, significant work stress, and use of multiple psychotropic medications contributed to the clinical expression of the disease. In women, relapses are more likely before menstruation (associated with the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle) and during pregnancy (2, 4, 5, 8, 30, 34, 37).

Medications can trigger or exacerbate acute attacks (9, 30, 34, 43, 49, 50, 65). Unfortunately, information for most drugs is insufficient to allow them to be classified as definitely harmful or safe, even as other drugs have been labeled harmful on the basis of inadequate evidence (4, 6, 30, 46). Little information exists about the safety of many psychotropic drugs, especially the newer antidepressants and atypical antipsychotics (30). A MEDLINE search from the 1960s to the present shed no light on medications that could have triggered acute porphyria attacks in our patient. We found no relevant information on any of his medications, including nefazodone, sertraline, valproic acid, perphenazine, venlafaxine, and olanzapine.

Hematin—most typically in the form of haem arginate—is the only form of heme currently approved for use in the United States during acute attacks (2, 4–7, 15, 18, 29, 32, 34). By negative feedback, heme suppresses aminolevulinic acid synthase, the rate-limiting enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway, with a resultant dramatic decline in porphyrin production (4, 5, 66, 67). Within hours of heme administration, the overproduction and overexcretion of aminolevulinic acid and porphobilinogen are normalized. Within 2 to 4 days, most patients with acute porphyria show clinical improvement (4, 5, 32, 66). As inhibitors of heme oxygenase, tin and zinc metalloporphyrins are alternatives to hematin. They have been shown to prolong remission when given with haem arginate (1, 4, 6, 24, 32). The metalloporphyrins’ side effects of cutaneous photosensitivity and potential toxicity limit their use; however, further evaluation is continuing (4). Our patient did not receive treatment with either hematin or metalloporphyrins because he did not have an acute attack at our medical center.

Genetics

Most of the porphyrias are inherited (2–4, 6, 10, 21, 30). Acute intermittent porphyria, variegate porphyria, and hereditary coproporphyria are inherited as autosomal dominant conditions with low penetrance (5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 18, 21, 31, 34, 35, 37, 38, 42–45). Therefore, 80%–90% of patients who have inherited the enzyme deficiency never have symptomatic disease and are considered to be “latent porphyrics” (1, 6, 8, 13, 30, 31, 34, 50). Only 10%–15% of the gene carriers have the clinical syndrome. One-third of patients have no family history, the condition probably having remained latent (inactive) or unidentified for several generations (4, 14, 34, 54). The autosomal recessive porphyrias (plumboporphyria and the homozygous counterparts of variegate porphyria and hereditary coproporphyria) are even rarer disorders than the autosomal dominant acute porphyrias (5, 7, 10, 31). The homozygous forms are often associated with more florid and severe clinical features (1, 10). Sequence analyses of the genes for all enzymes required for heme biosynthesis have revealed the porphyrias as highly heterogeneous, with multiple mutations underlying each type (5, 7, 10, 11, 23, 26, 31). For example, more than 120 mutations have been described for porphobilinogen deaminase (also called hydroxymethylbilane synthase or, in older literature, uroporphyrinogen I synthase) (31, 45), the enzyme involved in acute intermittent porphyria (20, 31). Therefore, DNA analysis is not yet of routine diagnostic value (4). It could provide a precise diagnosis of some of the porphyrias if the patient has one of the previously described point mutations, but this technique is currently confined to a few research laboratories (53, 54).

The only way to distinguish among the acute porphyrias is through biochemical analysis of urine and stool. Typically, patients with the autosomal dominant varieties present initially in adulthood, and those with homozygous variants present in early childhood. Symptomatic porphyria is thought to be more common in female than male patients (1, 2–4, 7, 10, 31, 34), with a female-male ratio of 5 to 1 (1, 4, 7, 10, 34).

Other Diagnostic Methods

Enzyme assays in erythrocytes or other cells or tissues are helpful in supporting the diagnosis but are best used to identify family members with latent disease (6, 7, 14, 22, 32, 62). The demonstration of decreased cellular enzyme activity proves the presence of the genetic defect but by itself is insufficient for implicating porphyria as the cause of a particular patient’s symptoms (1, 6, 14). Enzyme tests are often technically difficult and require tissues such as cultured fibroblasts, lymphocytes, or liver biopsy material; therefore, except for the use of erythrocyte porphobilinogen deaminase activity to confirm the diagnosis of acute intermittent porphyria, they are rarely used (32, 53, 54).

Plasma peak fluorescence is used with fecal porphyrin quantification for diagnosis of variegate porphyria (4, 32, 54, 68, 69). Plasma fluorescence emission scanning in variegate porphyria shows a characteristic peak between 621 and 628 nm (32, 53, 54, 68–71).

Conclusions

In retrospect, our patient’s clinical manifestations were strikingly similar to what is documented in the literature about the disease. He presented with a combination of neuropsychiatric and medical symptoms, all of which fit a diagnosis of porphyria but all of which are nonspecific (1). Diagnosis should be based on a high degree of awareness. In the present case, the diagnosis was entertained because of the following: 1) the etiologically obscure neurosis or psychosis after an extensive workup, 2) unexplained peripheral neuropathy, 3) indeterminate neurologic spells, 4) hyponatremia of unknown cause, and 5) a confusing constellation of symptoms. Results from quantitative tests for porphyrins in both urine and stool performed earlier may have proven valuable in making a diagnosis sooner.

|

|

|

|

Received May 13, 2002; revision received Oct. 12, 2002; accepted Oct. 15, 2002. From the Sleep Disorders Center and the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology, Mayo Clinic. Address reprint requests to Dr. Bostwick, Mayo Clinic, 200 First St., Rochester, MN 55905.

Figure 1. Urine and Stool Porphyrins in the Heme Biosynthetic Pathwaya

aEach step (arrow) is catalyzed by the enzyme named to the right of the step. The type of acute porphyria resulting from a deficiency of an enzyme is indicated to the right of that enzyme. Data are from Crimlisk (1), Ashley (2), Jensen et al. (3), Thadani et al. (4), Hift et al. (5), Scarlett and Brenner (7), Sassa and Kappas (31), and Bonkovsky and Barnard (32).

Figure 2. Diagnostic Algorithm for Possible Porphyric Syndromesa

aData from Bonkovsky and Barnard (32) and Hindmarsh et al. (53).

bQualitative screening tests should not be used.

1. Crimlisk HL: The little imitator—porphyria: a neuropsychiatric disorder. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997; 62:319-328Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Ashley EM: Anaesthesia for porphyria. Br J Hosp Med 1996; 56:37-42Medline, Google Scholar

3. Jensen NF, Fiddler DS, Striepe V: Anesthetic considerations in porphyrias. Anesth Analg 1995; 80:591-599Medline, Google Scholar

4. Thadani H, Deacon A, Peters T: Diagnosis and management of porphyria. Br Med J 2000; 320:1647-1651Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Hift RJ, Meissner PN, Kirsch RE: The clinical diagnosis, prevention and management of the hepatic porphyrias. Trop Gastroenterol 1997; 18:41-44Medline, Google Scholar

6. Tefferi A, Colgan JP, Solberg LA Jr: Acute porphyrias: diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc 1994; 69:991-995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Scarlett YV, Brenner DA: Porphyrias. J Clin Gastroenterol 1998; 27:192-198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Gazzaniga V: Uroporphyria: some notes on its ancient historical background. Am J Nephrol 1999; 19:159-162Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Hahn M, Bonkovsky HL: Multiple chemical sensitivity syndrome and porphyria: a note of caution and concern. Arch Intern Med 1997; 157:281-285Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Frank J, McGrath J, Lam H, Graham RM, Hawk JL, Christiano AM: Homozygous variegate porphyria: identification of mutations on both alleles of the protoporphyrinogen oxidase gene in a severely affected proband. J Invest Dermatol 1998; 110:452-455Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Frank J, Lam H, Zaider E, Poh-Fitzpatrick M, Christiano AM: Molecular basis of variegate porphyria: a missense mutation in the protoporphyrinogen oxidase gene. J Med Genet 1998; 35:244-247Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Harper P, Hybinette T, Thunell S: Large phlebotomy in variegate porphyria. J Intern Med 1997; 242:255-259Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Elder GH, Hift RJ, Meissner PN: The acute porphyrias. Lancet 1997; 349:1613-1617Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Mattern SE, Tefferi A: Acute porphyria: the cost of suspicion. Am J Med 1999; 107:621-623Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Kauppinen R: Management of the acute porphyrias. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 1998; 14:48-51Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Kauppinen R, Timonen K, Mustajoki P: Treatment of the porphyrias. Ann Med 1994; 26:31-38Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Lip GY, McColl KE, Moore MR: The acute porphyrias. Br J Clin Pract 1993; 47:38-43Medline, Google Scholar

18. Grandchamp B: Acute intermittent porphyria. Semin Liver Dis 1998; 18:17-24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Lim HW, Cohen JL: The cutaneous porphyrias. Semin Cutan Med Surg 1999; 18:285-292Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Petrides PE: Acute intermittent porphyria: mutation analysis and identification of gene carriers in a German kindred by PCR-DGGE analysis. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol 1998; 11:374-380Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Moore MR: Biochemistry of porphyria. Int J Biochem 1993; 25:1353-1368Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Ellefson RD, Ford RE: The porphyrias: characteristics and laboratory tests. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 1996; 24:S119-S125Google Scholar

23. Frank J, Poh-Fitzpatrick MB, King LE Jr, Christiano AM: The genetic basis of “Scarsdale Gourmet Diet” variegate porphyria: a missense mutation in the protoporphyrinogen oxidase gene. Arch Dermatol Res 1998; 290:441-445Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Straka JG, Rank JM, Bloomer JR: Porphyria and porphyrin metabolism. Annu Rev Med 1990; 41:457-469Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Sarkany RP: Porphyria: from Sir Walter Raleigh to molecular biology. Adv Exp Med Biol 1999; 455:235-241Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. McDonagh AF, Bissell DM: Porphyria and porphyrinology—the past fifteen years. Semin Liver Dis 1998; 18:3-15Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Poh-Fitzpatrick MB: The porphyrias. Dermatol Clin 1987; 5:55-61Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Laiwah AC, McColl KE: Management of attacks of acute porphyria. Drugs 1987; 34:604-616Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Bloomer JR, Bonkovsky HL: The porphyrias. Dis Mon 1989; 35:1-54Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Holroyd S, Seward RL: Psychotropic drugs in acute intermittent porphyria. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1999; 66:323-325Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Sassa S, Kappas A: Molecular aspects of the inherited porphyrias. J Intern Med 2000; 247:169-178Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Bonkovsky HL, Barnard GF: Diagnosis of porphyric syndromes: a practical approach in the era of molecular biology. Semin Liver Dis 1998; 18:57-65Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Djulbegovic B: Clinical problem-solving: still hazy after all these years (letter). N Engl J Med 1995; 332:333Medline, Google Scholar

34. Burgovne K, Swartz R, Ananth J: Porphyria: reexamination of psychiatric implications. Psychother Psychosom 1995; 64:121-130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Santosh PJ, Malhotra S: Varied psychiatric manifestations of acute intermittent porphyria. Biol Psychiatry 1994; 36:744-747Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Deacon AC, Peters TJ: Identification of acute porphyria: evaluation of a commercial screening test for urinary porphobilinogen. Ann Clin Biochem 1998; 35:726-732Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Regan L, Gonsalves L, Tesar G: Acute intermittent porphyria. Psychosomatics 1999; 40:521-523Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Boon FF, Ellis C: Acute intermittent porphyria in a children’s psychiatric hospital. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1989; 28:606-609Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Meyer UA, Schuurmans MM, Lindberg RL: Acute porphyrias: pathogenesis of neurological manifestations. Semin Liver Dis 1998; 18:43-52Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Mustajoki P: Variegate porphyria. Ann Intern Med 1978; 89:238-244Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Frank J, Christiano AM: Variegate porphyria: past, present and future. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol 1998; 11:310-320Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Deacon AC: Clinical problem-solving: still hazy after all these years. N Engl J Med 1995; 332:332-333Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Gonday G, Imbert Y, Maire JP, Leng B: [Variegata porphyria: up to date concerning a recent case.] Sem Hop Paris 1981; 57:397-403 (French)Medline, Google Scholar

44. Hamner MB: Obsessive-compulsive symptoms associated with acute intermittent porphyria. Psychosomatics 1992; 33:329-331Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Suarez JI, Cohen JL, Larkin J, Kernich CA, Hricik DE, Daroff RB: Acute intermittent porphyria: clinicopathologic correlation: report of a case and review of the literature. Neurology 1997; 48:1678-1683Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Gorchein A: Drug treatment in acute porphyria. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1997; 44:427-434Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Meissner P, Adams P, Kirsch R: Allosteric inhibition of human lymphoblast and purified porphobilinogen deaminase by protoporphyrinogen and coproporphyrinogen: a possible mechanism for the acute attack of variegate porphyria. J Clin Invest 1993; 91:1436-1444Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Hift RJ, Meissner PN, Corrigall AV, Ziman MR, Petersen LA, Meissner DM, Davidson BP, Sutherland J, Dailey HA, Kirsch RE: Variegate porphyria in South Africa, 1688-1996—new developments in an old disease. S Afr Med J 1997; 87:722-731Medline, Google Scholar

49. Meissner PN, Dailey TA, Hift RJ, Ziman M, Corrigall AV, Roberts AG, Meissner DM, Kirsch RE, Dailey HA: A R59W mutation in human protoporphyrinogen oxidase in decreased enzyme activity and is prevalent in South Africans with variegate porphyria. Nat Genet 1996; 13:95-97Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Khandheria U, Bhattacharya A: Acute intermittent porphyria: pathophysiology and treatment. Pharmacotherapy 1984; 4:144-150Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Lithner F: Could attacks of abdominal pain in cases of acute intermittent porphyria be due to intestinal angina? J Intern Med 2000; 247:407-409Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Tan CH, Yeow YK: Acute intermittent porphyria (AIP)—an unusual cause of acute confusional state: a case report. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1988; 17:451-453Medline, Google Scholar

53. Hindmarsh JT, Oliveras L, Greenway DC: Biochemical differentiation of the porphyrias. Clin Biochem 1999; 32:609-619Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Hindmarsh JT, Oliveras L, Greenway DC: Plasma porphyrins in the porphyrias. Clin Chem 1999; 45:1070-1076Medline, Google Scholar

55. Cripps DJ: Porphyria: genetic and acquired. IARC Sci Publ 1986; 77:549-566Medline, Google Scholar

56. Herrick AL, McColl KE: Lack of certainty on the diagnosis of acute intermittent porphyria: comment on the concise communication by Cohen et al (letter). Arthritis Rheum 1998; 41:188Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Buttery JE, Carrera AM, Pannall PR: Reliability of the porphobilinogen screening assay. Pathology 1990; 22:197-198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Schoenfeld N, Sztern M, Mamet R: Yeast, creatinine and false diagnosis of porphyria. Cell Mol Biol 1997; 43:81-88Medline, Google Scholar

59. Morton WE: Fecal porphyrin measurements are crucial for adequate screening for porphyrinopathy. Arch Dermatol 2000; 136:554-555Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Logan GM, Weimer MK, Ellefson M, Pierach CA, Bloomer JR: Bile porphyrin analysis in the evaluation of variegate porphyria. N Engl J Med 1991; 324:1408-1411Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Muhlbauer JE, Pathak MA, Tishler PV, Fitzpatrick TB: Variegate porphyria in New England. JAMA 1982; 247:3095-3102Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62. Herrick AL, Moore MR, Thompson GG, Ford GP, McColl KE: Cholelithiasis in patients with variegate porphyria. J Hepatol 1991; 12:50-53Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Brenner DA, Bloomer JR: The enzymatic defect in variegate porphyria: studies with human cultured skin fibroblasts. N Engl J Med 1980; 302:765-769Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Moore MR, McColl KE: Therapy of the acute porphyrias. Clin Biochem 1989; 22:181-188Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65. Bor M, Balogh K, Pusztai A, Tasnadi G, Hunyady L: Identification of acute intermittent porphyria carriers by molecular biologic methods. Acta Physiol Hung 1999; 86:147-153Medline, Google Scholar

66. McColl KE, Moore MR, Thompson GG, Goldberg A: Treatment with haematin in acute hepatic porphyria. Q J Med 1981; 50:161-174Medline, Google Scholar

67. Timonen K, Mustajoki P, Tenhunen R, Lauharanta J: Effects of haem arginate on variegate porphyria. Br J Dermatol 1990; 123:381-387Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

68. Long C, Smyth SJ, Woolf J, Murphy GM, Finlay AY, Newcombe RG, Elder GH: Detection of latent variegate porphyria by fluorescence emission spectroscopy of plasma. Br J Dermatol 1993; 129:9-13Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

69. Poh-Fitzpatrick MB: A plasma porphyrin fluorescence marker for variegate porphyria. Arch Dermatol 1980; 116:543-547Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

70. Da Silva V, Simonin S, Deybach JC, Puy H, Nordmann Y: Variegate porphyria: diagnostic value of fluorometric scanning of plasma porphyrins. Clin Chim Acta 1995; 238:163-168Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71. Enriquez de Salamanca R, Sepulveda P, Moran MJ, Santos JL, Fontanellas A, Hernandez A: Clinical utility of fluorometric scanning of plasma porphyrins for the diagnosis and typing of porphyrias. Clin Exp Dermatol 1993; 18:128-130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar