The Longitudinal Course of Borderline Psychopathology: 6-Year Prospective Follow-Up of the Phenomenology of Borderline Personality Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The syndromal and subsyndromal phenomenology of borderline personality disorder was tracked over 6 years of prospective follow-up. METHOD: The psychopathology of 362 inpatients with personality disorders was assessed with the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R) and borderline personality disorder module of the Revised Diagnostic Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders. Of these patients, 290 met DIB-R and DSM-III-R criteria for borderline personality disorder and 72 met DSM-III-R criteria for other axis II disorders (and neither criteria set for borderline personality disorder). Most of the borderline patients received multiple treatments before the index admission and during the study. Over 94% of the total surviving subjects were reassessed at 2, 4, and 6 years by interviewers blind to previously collected information. RESULTS: Of the subjects with borderline personality disorder, 34.5% met the criteria for remission at 2 years, 49.4% at 4 years, 68.6% at 6 years, and 73.5% over the entire follow-up. Only 5.9% of those with remissions experienced recurrences. None of the comparison subjects with other axis II disorders developed borderline personality disorder during follow-up. The patients with borderline personality disorder had declining rates of 24 symptom patterns but remained symptomatically distinct from the comparison subjects. Impulsive symptoms resolved the most quickly, affective symptoms were the most chronic, and cognitive and interpersonal symptoms were intermediate. CONCLUSIONS: These results suggest that symptomatic improvement is both common and stable, even among the most disturbed borderline patients, and that the symptomatic prognosis for most, but not all, severely ill borderline patients is better than previously recognized.

Clinical experience suggests that some patients with borderline personality disorder get better symptomatically over time, some stay about the same, and some get worse. However, little is actually known about the course of the syndromal phenomenology of borderline personality disorder (i.e., rates of remission and recurrence), and almost nothing is known about the fate of the subsyndromal phenomenology or symptoms of borderline personality disorder.

To date, we know of 17 small-scale studies of the short-term course of borderline personality disorder that have been described in published reports (1–20). Surprisingly, only five of these studies (5, 7, 12, 13, 15, 20) assessed the rate of remission of borderline personality disorder for their study groups, and none assessed either the rate of recurrence or the course of the symptoms that constitute borderline personality disorder. Remission rates in these studies ranged from 4% to 53% 1–7 years after the initial assessment, with a median rate of remission of 33%.

Reports on four large-scale follow-back studies of the long-term course of borderline personality disorder have also been published (21–24). Only one of these studies assessed the remission rate as part of the follow-up. Paris and his colleagues (23) found that 75% of their traced borderline patients no longer met the criteria for borderline personality disorder a mean of 15 years after the index admission.

In general, the results of these six studies (five short-term and one long-term) have been interpreted to suggest that borderline patients do poorly symptomatically in the short run but well symptomatically in the long run. Yet it is difficult to generalize from the results of these studies, all of which dealt with treated groups of borderline patients, because of a number of methodological limitations found in these studies: use of chart review or clinical interviews to diagnose borderline personality disorder, use of only one postbaseline reassessment, variable number of years of follow-up in the same study, no comparison group or use of less than optimal comparison subjects, nonblind postbaseline assessments, failure to study a full range of borderline psychopathology, and reliance on small subject groups with high attrition rates.

The current study improves on the methods of these earlier studies in seven important ways. First, semistructured interviews of documented reliability were used to assess borderline psychopathology at baseline and at each of three successive 2-year follow-up waves. Second, the phenomenology of borderline personality disorder was assessed at three separate follow-up points. Third, the interwave intervals were equal in length, each of 2 years’ duration. Fourth, a well-diagnosed group of axis II comparison subjects was also studied at each time point. Fifth, the follow-up raters were blind to all previously collected information on each subject, including original diagnostic status. Sixth, both the syndromal phenomenology of borderline personality disorder—rates of remission and recurrence—and the subsyndromal phenomenology of borderline personality disorder—the affective, cognitive, impulsive, and interpersonal symptoms of borderline personality disorder—were assessed. Seventh, we began with a large, socioeconomically diverse group of borderline patients and maintained a high retention rate across all three waves of follow-up.

Method

The current study is part of the McLean Study of Adult Development, a multifaceted longitudinal study of the course of borderline personality disorder. All subjects were initially inpatients at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass., who were admitted during a 3-year period (1992–1995). Each patient was initially screened to determine that he or she 1) was between the ages of 18 and 35 years, 2) had a known or estimated IQ of 71 or higher, 3) had no history or current symptoms of an organic condition that could cause psychiatric symptoms, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar I disorder, and 4) was fluent in English.

After the study procedures were explained, written informed consent was obtained. Each patient then met with a master’s-level psychologist blind to the patient’s clinical diagnoses for a thorough diagnostic assessment. Three semistructured interviews were administered. These diagnostic interviews were the 1) Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Axis I Disorders (SCID) (25), 2) Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R) (26), and 3) Diagnostic Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (27). Excellent levels of interrater reliability were obtained during the first 6 months of data collection (i.e., pairwise kappa of >0.85 for the DIB-R and DSM-III-R diagnoses of borderline personality disorder) and maintained throughout the course of the study (26, 27). The test-retest reliability of these diagnoses was also found to be >0.85 (26, 27). Treatment history was also assessed at baseline by using the Background Information Schedule (28)—a semistructured interview specifically designed to assess the psychosocial functioning and treatment histories of borderline patients and patients with other axis II disorders. The interrater and test-retest reliability and the concurrent validity of the Background Information Schedule have been found to be good to excellent (28).

At each follow-up wave, diagnostic status and treatment history were reassessed through interview methods similar to the baseline procedures by staff members blind to the baseline diagnoses. After informed consent was obtained, our diagnostic battery was readministered (a change version of the SCID, the DIB-R, and the Revised Diagnostic Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders) along with the Revised Borderline Follow-Up Interview—the follow-up analogue to the Background Information Schedule.

The relationship between baseline demographic variables and diagnosis was assessed by using logistic regression modeling. Data pertaining to the subsyndromal phenomenology of borderline personality disorder were assembled in panel format (i.e., multiple records per patient, with one record for each assessment period for which data were available). Random effects regression modeling methods assessing the role of diagnosis and time and controlling for clinically important baseline covariates (gender, race, age, socioeconomic status, Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score, and number of previous treatment modalities) were used in all analyses of symptom-level data (29). In this modeling work, probit analyses of binary dependent variables (symptom present/absent) were used. The random effects were the subjects, and the fixed effects were diagnosis, time, and the six covariates just mentioned. Interactions between diagnosis and time and between diagnosis and significant covariates were checked in this modeling. Model fits were checked by examining partial residual plots. Because of the multiple comparisons involved in the analyses of symptom-level panel data, Bonferroni-type corrections were applied to the p values for the main effects of diagnosis and time. As there were 24 such comparisons, this resulted in an adjusted p value of 0.0021 (0.05/24).

Random effects regression modeling was also used to assess the relationship between treatment modalities and diagnostic status (borderline personality disorder versus other axis II disorders). As there were nine such comparisons, this resulted in an adjusted p value of 0.0056 (0.05/9).

Results

Baseline diagnostic interviews were administered to 378 consecutive inpatients at McLean Hospital who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of these patients, 290 met both the DIB-R and DSM-III-R criteria for borderline personality disorder, and 72 met the DSM-III-R criteria for at least one nonborderline axis II disorder (and neither criteria set for borderline personality disorder). Sixteen others were excluded from further study because either they met the criteria for schizophrenia (N=2) or bipolar I disorder (N=2) or they failed to meet the DSM-III-R criteria for any axis II disorder (N=12).

As previously reported (30), the possibility of patients being given a false positive diagnosis of borderline personality disorder because of a comorbid axis I disorder that overlapped with the phenomenology of borderline personality disorder was carefully assessed in this subject group, and no such diagnoses were found. Of the 72 comparison subjects, 4.2% (N=3) met the DSM-III-R criteria for a personality disorder in the “odd” cluster, 33.3% (N=24) had disorders in the “anxious” cluster, 18.1% (N=13) had diagnoses in the “dramatic” cluster, and 52.8% (N=38) met the DSM-III-R criteria for personality disorder not otherwise specified (which was operationally defined in the Revised Diagnostic Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders as meeting all but one of the required number of criteria for at least two of the 13 axis II disorders described in DSM-III-R).

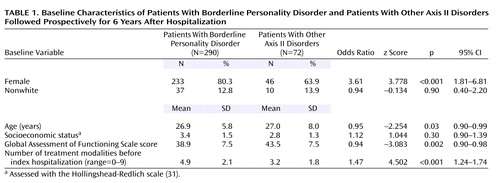

Baseline demographic data are presented in Table 1. As can be seen, the borderline patients were significantly discriminated from the axis II comparison subjects by the higher proportion of women, younger age, lower Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score, and more previous treatment modalities. In addition, the 362 patients came from a broad socioeconomic spectrum. More specifically, we found the following socioeconomic distribution using the 5-point Hollingshead-Redlich scale (31), in which I=highest, V=lowest: 17.7% were in level I (N=64), 16.0% were in level II (N=58), 19.1% were in level III (N=69), 18.0% were in level IV (N=65), and 29.3% were in level V (N=106).

At 2 years, 275 borderline patients and 67 axis II comparison subjects were reinterviewed, 269 and 64 were reinterviewed at 4 years, and 264 and 63 were assessed at 6 years. By this time, 26 borderline patients were no longer in the study: 11 committed suicide, three others died of natural causes, nine discontinued their participation, and three were lost to follow-up. Of the comparison subjects, one committed suicide, five discontinued their participation, and three were lost to follow-up. Of all surviving subjects, over 94% were reinterviewed at all three follow-up waves.

Syndromal Phenomenology

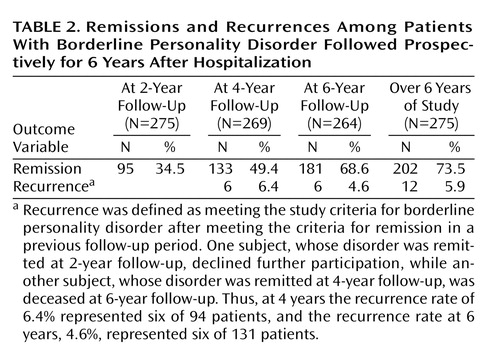

Table 2 summarizes the rates of remission and recurrence found in the borderline group over the 6 years of prospective follow-up. Remission was defined as no longer meeting either of our criteria sets for borderline personality disorder (DIB-R and DSM-III-R). Recurrence was defined as meeting both criteria sets for borderline personality disorder after meeting the criteria for a remission in a previous follow-up period.

About one-third of our borderline subjects met the criteria for remission at 2-year follow-up, about one-half at 4 years, about two-thirds at 6 years, and about three-quarters over the course of the entire 6 years of follow-up. Slightly less than 6% met the criteria for recurrence of borderline personality disorder after experiencing a remission in the previous follow-up period(s).

Of the 202 borderline patients who experienced a remission of borderline personality disorder, 47.0% (N=95) first experienced remission by the 2-year follow-up, 26.7% (N=54) first had a remission by the 4-year follow-up, and 26.2% (N=53) experienced remission by the 6-year follow-up. Recurrences were experienced by only 12 patients who had remissions: six experienced their first recurrence at 4-year follow-up, and another six had their first recurrence at 6-year follow-up. Four of the six borderline patients who experienced a recurrence of borderline personality disorder at year 4 had a second remission at year 6. In addition, no axis II comparison subject was found to satisfy the study criteria for borderline personality disorder at any time during the 6 years of follow-up.

Subsyndromal Phenomenology

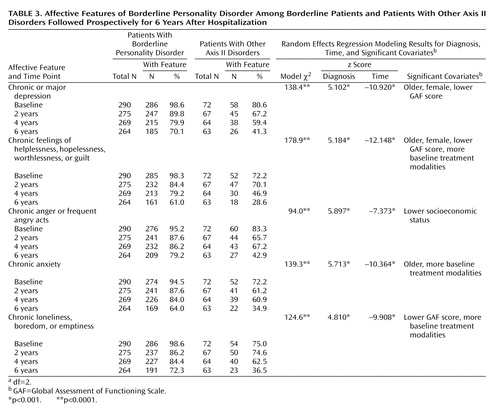

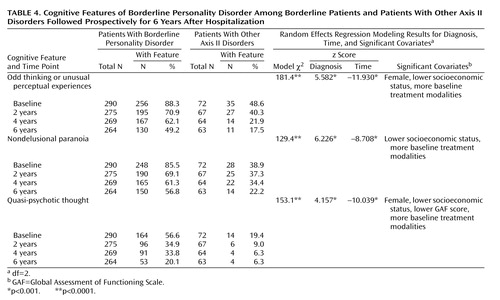

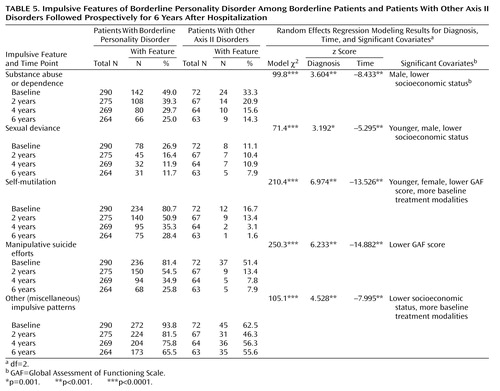

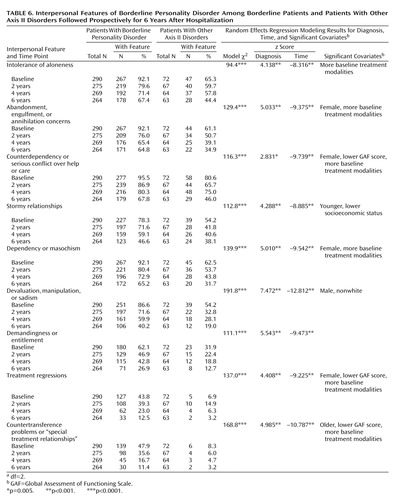

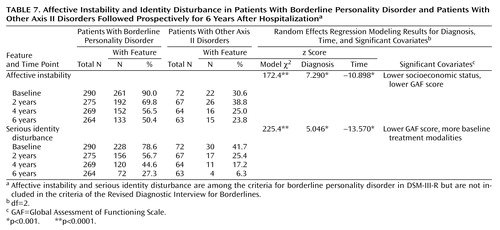

The subsyndromal phenomenology of borderline personality disorder was examined by determining the rates of 24 symptoms exhibited by the borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects over the 6 years of prospective follow-up. Of these 24 symptoms, 22 are contained in the DIB-R and fall into four general categories: affective features (Table 3), cognitive features (Table 4), impulsive features (Table 5), and interpersonal features (Table 6). Two DSM-III-R criteria are not assessed by the DIB-R: affective instability and serious identity disturbance (Table 7). The rates of all 24 symptoms declined significantly over time for all subjects considered together. In addition, 23 of the 24 symptoms (all but counterdependency) remained significantly more common among borderline patients than axis II comparison subjects.

Psychiatric Treatment

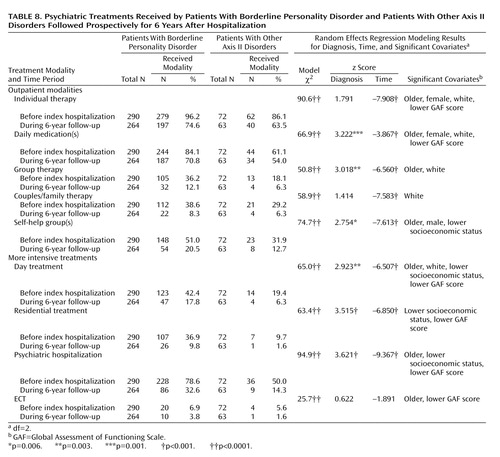

Table 8 details the rates of borderline patients and comparison subjects who participated in each of nine modalities during the first and last of the study’s four time periods. (Rates of each modality at the 2- and 4-year follow-ups, which declined from the prior time periods, are not shown but are available from the authors on request.) As can be seen, a high percentage of those in both groups had been in treatment before the index admission and remained in treatment, particularly outpatient treatment, during the 6-year follow-up period. The borderline patients were significantly more likely than the axis II comparison subjects to have participated in five of the nine modalities studied (pharmacotherapy, group therapy, day treatment, residential treatment, and psychiatric hospitalization). However, at the stringent Bonferroni-corrected significance level of p=0.0056, the rates of individual therapy, couples/family therapy, self-help groups, and ECT did not distinguish between the groups. In addition, the rates of all treatment modalities studied except ECT declined significantly over time for all subjects considered together.

Discussion

Major Findings

Three major findings emerged from this study. The first is that remissions were common, increasing over the course of 6 years of follow-up and eventually including almost three-quarters of the borderline patients who were reinterviewed at least once. The rate of remission that we found at 2-year follow-up (34.5%) is consistent with the 30%–40% found in most earlier studies that assessed the 2–3-year outcome of borderline personality disorder (5, 7, 12, 15). In addition, the approximately 50% remission rate that we found at 4-year follow-up is consistent with the 53% remission rate found by Links et al. (13) at 5–7-year follow-up. However, to our knowledge, the steady progression of remission rates across the three follow-up periods is a new finding. Also apparently new is the finding that about 75% of our borderline patients experienced a remission sometime during the 6 years of follow-up. This rate is almost identical to the remission rate found by Paris et al. (23) a mean of 15 years after their patients’ index admission. This finding suggests that the majority of borderline patients experience substantial reductions in their symptoms far sooner than previously known. In addition, it highlights the fact that borderline personality disorder has a dichotomous outcome, at least after 6 years of follow-up. While three-quarters of the borderline patients in the current study were in the ever-remitted group after 6 years of follow-up, one-quarter remained in the never-remitted group.

The second finding is that recurrences were rare. This also appears to be a new finding and suggests that once a borderline patient has met criteria for a remission of borderline personality disorder, the likelihood of a substantial and sustained recrudescence of symptoms is small. This finding contrasts with the high recurrence rates found in naturalistic studies of the course of episodic disorders, such as major depression (32) and bipolar disorder (33). The finding that borderline patients have a much longer time to first remission than is typical of patients with mood disorder (34, 35) also suggests that borderline personality disorder is a more stable disorder than episodic axis I disorders. The reasons for this relative stability of illness and robustness of improved health are not clear. Borderline patients typically suffer from a sense of being aggrieved that is difficult, but not impossible, to assuage (36). Once they feel better understood, they are often able to learn more adaptive ways of handling their many and varied symptoms. This learning seems to lead to true developmental change, and once this type of growth or maturity has been achieved, it is not likely to be easily lost. In this way and for these reasons, borderline patients with remissions may be relatively resistant to recurrences of their disorder.

The third finding is that borderline patients experienced declining rates of each of the 24 symptoms studied but remained symptomatically distinct from axis II comparison subjects over time. More specifically, the borderline patients were found to exhibit greater psychopathology than the axis II comparison subjects in 23 of the 24 symptom areas studied. These interrelated findings of symptomatic improvement and distinctness also appear to be new, as we know of no previous study that has assessed the longitudinal course of the symptoms of borderline personality disorder or compared them to those exhibited by a comparison group.

Course of Symptom Sectors

The results of this study also suggest that different sectors of borderline psychopathology have different longitudinal patterns. The affective symptoms of borderline personality disorder were the least likely to resolve for the borderline patients; they were present in 61.0% to 79.2% of these patients at 6-year follow-up. While this is a significant decline from the 94.5% to 98.6% found at baseline, it indicates that the majority of borderline patients continued to suffer from a range of dysphoric affects. Previously, we detailed the dysphoric states specific to borderline personality disorder (37), and the results of this study suggest that many of these states are relatively resistant to change. The clinical implications of this finding are unclear. The majority of borderline patients remained in treatment throughout the follow-up periods, and thus, this lack of symptom resolution is probably not due to a failure to treat these symptoms. Rather, it may be that these affective symptoms are core features of a borderline patient’s identity or temperament and, as such, are relatively resistant to change. Whether new treatments aimed at this sector of borderline psychopathology can be developed and would prove useful is an open question.

The impulsive symptoms of borderline personality disorder were the most likely to resolve for borderline patients. Both self-mutilation and suicide efforts were reported by about 81% of the borderline patients at baseline. By the 6-year follow-up, the rates for both of these forms of self-destructive behavior had declined to nearly 25%. In a like manner, substance abuse declined from a baseline high of 49.0% to 25.0% at 6-year follow-up, and sexual deviance (mostly promiscuity) had declined from 26.9% to 11.7%. In contrast, other forms of impulsivity, which included eating binges, verbal outbursts, and spending sprees, declined only from 93.8% at baseline to 65.5% at 6-year follow-up.

The cognitive and interpersonal symptoms of borderline personality disorder occupy an intermediate position in terms of longitudinal course. While all three cognitive and all nine interpersonal symptoms declined significantly over time, some declined to substantially lower levels than others. A history of quasi-psychotic thought was reported by over one-half of the borderline patients at baseline, but by 6-year follow-up only one-fifth reported experiencing such transitory, circumscribed delusions and hallucinations. Both odd thinking or unusual perceptual experiences (mostly overvalued ideas, recurrent illusions, depersonalization, and derealization) and nondelusional paranoia were much more common at baseline, being reported by over 85% of the borderline patients. After 6 years of follow-up, about one-half of the borderline patients still reported these symptoms.

As already noted, the DIB-R assesses the presence of nine interpersonal features. Two of these features, treatment regressions and countertransference problems, initially reported by fewer than 50% of the borderline patients, were reported by only about 10% of the borderline patients by 6-year follow-up. Three other patterns (stormy relationships, devaluation/manipulation/sadism, and demandingness/entitlement) were reported by about 60%–85% of the borderline patients at baseline and about one-quarter to less than one-half at 6-year follow-up. The third group of interpersonal symptoms (intolerance of aloneness, abandonment concerns, counterdependency, and dependency/masochism) were originally reported by over 90% of the borderline patients, and over 60% of these patients were still reporting these symptoms after 6 years of prospective follow-up.

Taken together, the results of this study suggest that borderline personality disorder is characterized by two distinct types of symptoms. One type, including self-mutilation, suicide efforts, quasi-psychotic thought, treatment regressions, and countertransference problems, is a manifestation of acute illness. These symptoms, which have been found to be particularly good markers for the borderline diagnosis (38) and which are often associated with treatment crises and/or the need for hospitalization, seem to resolve relatively quickly over time and were only present in a minority of borderline patients followed for 6 years. The other type of symptom represents the more temperamental or enduring aspects of borderline personality disorder. These symptoms, such as chronic feelings of anger or emptiness, suspiciousness, difficulty tolerating aloneness, and abandonment concerns, seem to resolve more slowly and were still reported by a majority of borderline patients 6 years after the index admission.

Relationship Between Symptoms and Treatment

It is clear from the treatment data that the current study concerns the natural history of a highly treated group of patients (both borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects). This is not surprising as clinical experience suggests that many, if not most, borderline patients with a history of psychiatric hospitalization have extensive treatment histories. However, the results of the current study also suggest that a high percentage of those with other forms of axis II pathology who were once hospitalized continue to participate in outpatient treatment (but not more intensive forms of treatment).

Unfortunately, the naturalistic design of this study prevents us from being able to determine whether treatment was helpful, harmful, or both at different points in time. This is so because the patients were not randomly assigned to treatment modalities or clinicians but, rather, chose the treatments they received. This, in turn, might have been influenced by a variety of factors, such as the severity of their symptoms, their psychological mindedness, and the type of insurance they had. In addition, the treatment approach and quality were not standardized, as hundreds of clinicians in the community provided most of the care received by the patients in this study.

Limitations and Directions for Further Research

The most important limitation of the current study is that the entire group of borderline patients originally comprised very disturbed inpatients. Whether these results would generalize to never-hospitalized outpatients is unclear. One might expect that less disturbed outpatients would do better symptomatically over time than recovering inpatients, but only longitudinal studies of this type of mildly to moderately disturbed patient with borderline personality disorder will answer this question.

Conclusions

Taken together, the results of this study suggest that symptomatic improvement is both common and stable among once highly disturbed (and typically heavily treated) borderline patients. These results also suggest that the symptomatic prognosis for most, but not all, borderline patients with illness of this severity is better than previously recognized.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Received July 13, 2001; revisions received Nov. 14, 2001, and March 26, June 20, Aug. 6, and Aug. 21, 2002; accepted Sept. 3, 2002. From the Laboratory for the Study for Adult Development, McLean Hospital; and the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Address reprint requests to Dr. Zanarini, McLean Hospital, 115 Mill Street, Belmont, MA 02478; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants MH-47588 and MH-62169.

1. Grinker RR, Werble B, Drye R: The Borderline Syndrome: A Behavioral Study of Ego Functions. New York, Basic Books, 1968Google Scholar

2. Werble B: Second follow-up study of borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1970; 23:3-7Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Gunderson JG, Carpenter WT Jr, Strauss JS: Borderline and schizophrenic patients: a comparative study. Am J Psychiatry 1975; 132:1257-1264Link, Google Scholar

4. Carpenter WT, Gunderson JG: Five year follow-up comparison of borderline and schizophrenic patients. Compr Psychiatry 1977; 18:567-571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Pope HG, Jonas JM, Hudson JI, Cohen BM, Gunderson JG: The validity of DSM-III borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:23-30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Akiskal HS, Chen SE, Davis GC, Puzantian VR, Kashgarian M, Bolinger JM: Borderline: an adjective in search of a noun. J Clin Psychiatry 1985; 46:41-48Medline, Google Scholar

7. Barasch A, Frances A, Hurt S, Clarkin J, Cohen S: Stability and distinctness of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:1484-1486Link, Google Scholar

8. Perry JC, Cooper SH: Psychodynamics, symptoms, and outcome in borderline and antisocial personality disorders and bipolar type II affective disorder, in The Borderline: Current Empirical Research. Edited by McGlashan TH. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1985, pp 19-41Google Scholar

9. Nace EP, Saxon JJ Jr, Shore N: Borderline personality disorder and alcoholism treatment: a one-year follow-up study. J Stud Alcohol 1986; 47:196-200Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Tucker L, Bauer SF, Wagner S, Harlam D, Sher I: Long-term hospital treatment of borderline patients: a descriptive outcome study. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:1443-1448Link, Google Scholar

11. Modestin J, Villiger C: Follow-up study on borderline versus nonborderline personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry 1989; 30:236-244Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Links PS, Mitton JE, Steiner M: Predicting outcome for borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry 1990; 31:490-498Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Links PS, Heslegrave RJ, Van Reekum R: Prospective follow-up study of borderline personality disorder: prognosis, prediction of outcome, and axis II comorbidity. Can J Psychiatry 1998; 42:265-270Google Scholar

14. Mehlum L, Friis S, Irion T, Johns S, Karterud S, Vaglum P, Vaglum S: Personality disorders 2-5 years after treatment: a prospective follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991; 84:72-77Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Stevenson J, Meares R: An outcome study of psychotherapy for patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:358-362Link, Google Scholar

16. Linehan MM, Heard HL, Armstrong HF: Naturalistic follow-up of a behavioral treatment for chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:971-974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Sandell R, Alfredsson E, Berg M, Crafoord K, Lagerlof A, Arkel I, Cohn T, Rasch B, Rugolska A: Clinical significance of outcome in long-term follow-up of borderline patients at a day hospital. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993; 87:405-413Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Antikainen R, Hintikka J, Lehtonen J, Koponen H, Arstila A: A prospective three-year follow-up study of borderline personality disorder inpatients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1995; 92:327-335Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Najavits LM, Gunderson JG: Better than expected: improvements in borderline personality disorder in a 3-year prospective outcome study. Compr Psychiatry 1995; 36:296-302Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Senol S, Dereboy C, Yuksel N: Borderline disorder in Turkey: a 2- to 4-year follow-up. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1997; 32:109-112Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Plakun EM, Burkhardt PE, Muller JP: 14-year follow-up of borderline and schizotypal personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry 1985; 26:448-455Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. McGlashan TH: The Chestnut Lodge follow-up study, III: long-term outcome of borderline personalities. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:20-30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Paris J, Brown R, Nowlis D: Long-term follow-up of borderline patients in a general hospital. Compr Psychiatry 1987; 28:530-536Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Stone MH: The Fate of Borderline Patients. New York, Guilford, 1990Google Scholar

25. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:624-629Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Vujanovic AA: The interrater and test-retest reliability of the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R). J Personal Disord 2002; 16:270-276Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR: Attainment and maintenance of reliability of axis I and II disorders over the course of a longitudinal study. Compr Psychiatry 2001; 42:369-374Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Khera GS, Bleichmar J: Treatment histories of borderline inpatients. Compr Psychiatry 2001; 42:144-150Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Green WH: Econometric Analysis, 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ, Prentice-Hall, 2000, pp 812-837Google Scholar

30. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo ED, Sickel AE, Trikha A, Levin A, Reynolds V: Axis I comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1733-1739Link, Google Scholar

31. Hollingshead AB: Two-Factor Index of Social Position. New York, Psychological Corp, 1957Google Scholar

32. Mueller TI, Leon AC, Keller MB, Solomon DA, Endicott J, Coryell W, Warshaw M, Maser JD: Recurrence after recovery from major depressive disorder during 15 years of observational follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1000-1006Abstract, Google Scholar

33. Coryell W, Endicott J, Maser JD, Mueller T, Lavori P, Keller M: The likelihood of recurrence in bipolar affective disorder: the importance of episode recency. J Affect Disord 1995; 14:201-206Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Shea MT, Warshaw M, Maser JD, Coryell W, Endicott J: Recovery from major depression: a 10-year prospective follow-up across multiple episodes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:989-991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Tohen M, Hennen J, Zarate CM Jr, Baldessarini RJ, Strakowski SM, Stoll AL, Faedda GL, Suppes T, Gebre-Medhin P, Cohen BM: Two-year syndromal and functional recovery in 219 cases of first-episode major affective disorder with psychotic features. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:220-228Link, Google Scholar

36. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR: Emotional hypochondriasis, hyperbole, and the borderline patient. J Psychother Pract Res 1994; 3:25-36Medline, Google Scholar

37. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, DeLuca CJ, Hennen J, Khera GS, Gunderson JG: The pain of being borderline: dysphoric states specific to borderline personality disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1998; 6:201-207Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL: Discriminating borderline personality disorders from other axis II disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:161-167Link, Google Scholar