Combination of a Mood Stabilizer With Risperidone or Haloperidol for Treatment of Acute Mania: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Comparison of Efficacy and Safety

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study assessed the efficacy and safety of risperidone as an adjunctive agent to mood stabilizers in the treatment of acute mania. METHOD: This 3-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study included 156 bipolar disorder patients with a current manic or mixed episode who received a mood stabilizer (lithium or divalproex) and placebo, risperidone, or haloperidol. The primary efficacy measure was the Young Mania Rating Scale. Other assessments used the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, the Clinical Global Impression scale, and safety measures. RESULTS: The trial was discontinued by 25 (49%) of the 51 placebo group patients, 18 (35%) of the 52 risperidone group patients, and 28 (53%) of the 53 haloperidol group patients. Mean modal doses were 3.8 mg/day (SD=1.8) of risperidone and 6.2 mg/day (SD=2.9) of haloperidol. Significantly greater reductions in Young Mania Rating Scale scores at endpoint and over time were seen in the risperidone group and in the haloperidol group, compared with the placebo group. Young Mania Rating Scale total scores improved with risperidone and with haloperidol both in patients with psychotic features and in those without psychotic features at baseline. Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale total scores at endpoint were significantly higher in the haloperidol patients than in the placebo patients. Antiparkinsonian medications were received by 8%, 17%, and 38% of patients in the placebo, risperidone, and haloperidol groups, respectively. CONCLUSIONS: Risperidone plus a mood stabilizer was more efficacious than a mood stabilizer alone, and as efficacious as haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer, for the rapid control of manic symptoms and was well tolerated.

Acute manic episodes can have devastating consequences (1; DSM-IV). Management of acute mania is directed at rapidly controlling the irritability, agitation, impulsivity, aggression, and psychotic symptoms that characterize the hyperaroused state in manic and mixed episodes. The primary goal of treatment for mania is to restore behavioral control as quickly as possible so as to minimize dangerousness to self and others and limit the high economic, social, and personal costs of manic episodes. Although many experts agree that combination therapy may offer an advantage over monotherapy (2), few controlled studies offering evidence for the advantages of this approach have been performed.

In the United States, mood stabilizers, principally lithium and divalproex, are standard treatment choices for the management of bipolar disorder (2–4). Double-blind studies have demonstrated the superior efficacy of these agents compared with placebo as monotherapy for mania (5). However, these studies have also indicated that many patients treated for up to 3 weeks with lithium or divalproex retain clinically significant manic symptoms. Higher serum levels of the mood stabilizers have been associated with greater efficacy but are complicated by more adverse effects and secondary noncompliance (5, 6).

Conventional antipsychotics have been used alone to achieve rapid control of acute manic symptoms (7), but their efficacy appears to be modest (8, 9). In addition, conventional antipsychotics are often poorly tolerated. Although atypical antipsychotics are generally better tolerated than the conventional agents (10), we are aware of only three controlled trials assessing the effects of atypical antipsychotics in patients with bipolar disorder. Risperidone, haloperidol, and lithium were equivalent in efficacy in a 28-day double-blind study involving 45 inpatients with mania (11). In a 3-week double-blind study, olanzapine was superior to placebo for treatment of symptoms of acute mania in 139 patients for whom treatment with mood stabilizers had failed (12). A 4-week replication study again found olanzapine monotherapy superior to placebo in 115 patients hospitalized for acute mania (13). These reports are encouraging and suggest that the efficacy of treatment with atypical antipsychotics as monotherapy appears to be of the same magnitude as that for mood stabilizer monotherapy.

Because rapid control of acute mania is desired, adjunctive agents, including combinations of two mood stabilizers or of a mood stabilizer with an antipsychotic agent, are widely used (14). Although this approach has been recommended in published treatment guidelines (2, 3), few well-controlled studies of combination therapies have been conducted. For patients with bipolar I disorder who were receiving lithium, adjunctive treatment with gabapentin was equivalent to placebo for treatment acute mania or hypomania (15). The combination of a mood stabilizer plus an antipsychotic agent has been widely used for rapid control of acute manic episodes (14, 16). Muller-Oerlinghausen et al. (17) reported that adjunctive valproate plus a conventional antipsychotic provided greater symptom reduction than placebo and at a lower mean dose of the antipsychotic agent. Concern about possible additive adverse effects (particularly extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia) with combination therapy has limited the use of conventional antipsychotics for patients with bipolar disorder (18).

Evidence from several small trials (19–22) and a survey of a hospital database (23) have suggested that risperidone may be useful in patients with bipolar and affective disorders. In a 3-week double-blind, placebo-controlled study involving manic patients, we evaluated the effects of risperidone and haloperidol in combination with a mood stabilizer. To our knowledge, this study also provides the first controlled comparison of a typical and atypical antipsychotic in the treatment of mania.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were patients aged 18–65 years with a history of bipolar disorder and at least one prior manic episode who were hospitalized for treatment of a manic episode in one of 20 centers. Inclusion criteria included a minimum score of 20 on the Young Mania Rating Scale (24) and a DSM-IV diagnosis of bipolar disorder, with the most recent episode manic or mixed (296.4x, 296.6x). Patients had to be medically stable according to a pretrial physical examination, medical history, and electrocardiography. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Exclusion criteria included another DSM-IV axis I diagnosis that required psychopharmacologic treatment; use of disallowed concomitant therapy; history of drug or alcohol abuse or dependence within 1 month before study entry; seizure disorder requiring medication; participation in an investigational drug trial within 30 days before the start of the trial; known sensitivity to risperidone, lithium, divalproex, or carbamazepine; use of clozapine within 1 month before study entry; use of depot neuroleptics within one cycle before study entry; and laboratory values outside the normal range. Women of childbearing potential who were without adequate contraception were also excluded.

Procedure

Patients were randomly assigned to receive placebo, risperidone, or haloperidol under double-blind conditions in addition to a mood stabilizer (lithium or divalproex) for up to 3 weeks. Random assignment was stratified by mood stabilizer (lithium or divalproex) and was preceded by a washout period of up to 3 days for patients who had received any disallowed concomitant medications such as antipsychotics other than risperidone or haloperidol or mood stabilizers other than lithium or divalproex.

Patients who had completed either the 3-week double-blind study or at least 7 days of double-blind treatment but who terminated because of lack of efficacy or an adverse event were eligible to enter a 10-week open-label extension study. Data from the 10-week study will be reported elsewhere.

Assessments

All patients received a psychiatric evaluation to establish the diagnosis of bipolar disorder. During the double-blind phase, the Young Mania Rating Scale was completed at baseline screening and days 1, 8, 15, and 22. The Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale (25) was completed on days 1, 8, 15, and 22. Severity of extrapyramidal symptoms was rated with the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (26) on days 1, 8, 15, and 22. Information on adverse events was obtained on days 1, 3, 8, 15, and 22. Electrocardiography and standard laboratory tests were performed at screening and day 22. Vital signs were measured at screening and days 1, 8, 15, and 22. Serum levels of the mood stabilizer were measured at screening and days 1 and 22. Patients received a physical examination at screening and on day 22 and were weighed on days 1 and 22.

Dosing Schedule

The study employed a flexible dosing schedule for risperidone, haloperidol, and the mood stabilizers. In addition to receiving lithium or divalproex, on days 1 and 2 of the double-blind phase, patients received 2 mg/day of risperidone (2 tablets), 4 mg/day of haloperidol (2 tablets), or 2 tablets of placebo. On days 3 and 4, the doses could be maintained, reduced to 1 tablet, or increased to 4 mg/day of risperidone, 8 mg/day of haloperidol, or 4 tablets of placebo. On days 5 to 21, the doses could be increased to 6 mg/day of risperidone, 12 mg/day of haloperidol, or 6 tablets of placebo.

If a patient was not receiving lithium or divalproex at study entry, treatment with one or the other was started immediately after consent was provided. Mood stabilizers could not be switched for lack of efficacy. If a patient experienced an adverse event attributed to the mood stabilizer, the dose could be reduced. If the adverse event persisted, the mood stabilizer could be switched. For the data analyses, three patients who switched mood stabilizers remained in their original mood stabilizer group (mood stabilizer groups were used as strata).

Investigators were instructed to adjust doses of the mood stabilizers to obtain serum concentrations in the usual therapeutic range: for divalproex, 50–120 μg/ml (trough); for lithium, 0.6–1.4 meq/liter (12 hours after last dose).

Concomitant Medications

The following were not permitted during the trial: antipsychotics other than risperidone or haloperidol; mood stabilizers other than lithium or divalproex; benzodiazepines other than temazepam, oxazepam, or flurazepam for sleep; lorazepam for agitation after day 7 (however, up to 4 mg/day was permitted during days 1 to 7 for sleep); antiparkinsonian medication at baseline; and antidepressants at entry into the double-blind phase.

Efficacy Measures

Severity of the illness and psychopathology were measured with the Young Mania Rating Scale (range=0–60), the CGI severity scale (from 0, “not ill,” to 7, “extremely severe”), and the CGI change scale (from 1, “very much better,” to 7, “very much worse”). The primary measure of efficacy was the change in the mean Young Mania Rating Scale total score from baseline to endpoint. Endpoint was the last available postbaseline assessment. Secondary measures included changes from baseline in severity of illness as reflected in CGI change scale scores.

Statistical Analysis

All patients who were randomly assigned to treatment groups and had at least one postbaseline assessment were included in the efficacy analysis. All patients who were randomly assigned to treatment groups were included in the safety analysis. The primary time point was the endpoint of the double-blind phase (i.e., the last available observation for each patient during the double-blind phase), and the primary comparison was between risperidone and placebo. Haloperidol was included as an active comparator to assess the sensitivity of the trial. An analysis of covariance model was used to test differences between treatments at endpoint. The model included factors for treatment, investigator, and type of mood stabilizer and baseline score on the Young Mania Rating Scale as a covariate. Young Mania Rating Scale total scores at all time points in the double-blind treatment phase were analyzed jointly by means of a repeated-measures model. Investigator, type of mood stabilizer, and treatment over time were used as factors in the model, with an assumption that observations of each subject were correlated with an autoregression variance and covariance structure. Gehan’s generalized Wilcoxon test (27) was used to evaluate differences in time to discontinuation, and the Van Elteren test (28) (controlling for investigator) was used to evaluate differences in CGI change scores.

Results

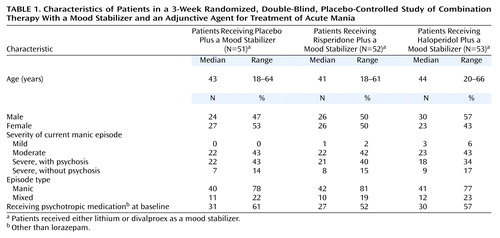

Characteristics of the patients in the three treatment groups are summarized in Table 1. The groups included equivalent proportions of men and women, all of whom received a DSM-IV diagnosis of bipolar disorder, manic or mixed episode. The severity specifier for the diagnosis was moderate or severe for most patients, and psychotic features were present in more than one-third of the patients. Differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between the groups at baseline were not significant.

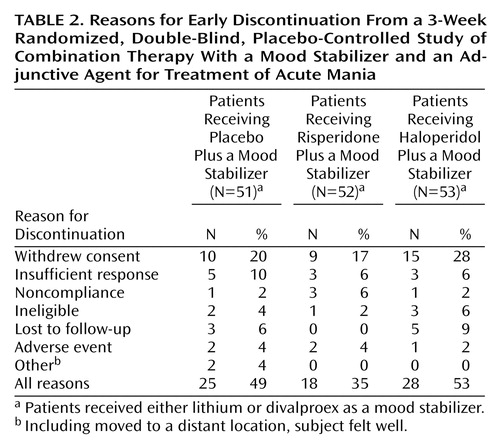

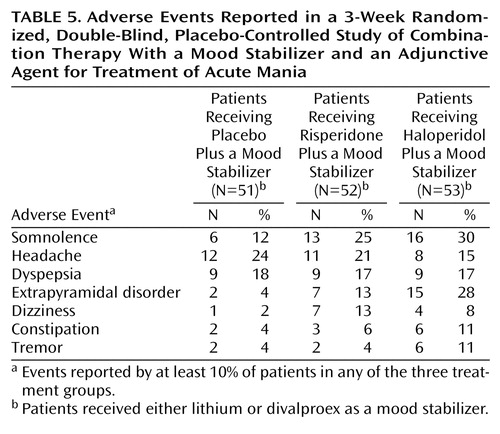

Of the 180 patients who were recruited, 158 were randomly assigned to a treatment group; 156 of these received at least one dose of study medication. The trial was discontinued by 25 (49%) of the 51 patients in the placebo plus mood stabilizer group, 18 (35%) of the 52 patients in the risperidone plus mood stabilizer group, and 28 (53%) of the 53 patients in the haloperidol plus mood stabilizer group (Figure 1). Reasons for early discontinuation are shown in Table 2. Time to premature discontinuation was significantly shorter for the patients who received placebo plus a mood stabilizer (25% had discontinued by day 9) than for the patients who received risperidone plus a mood stabilizer (25% had discontinued by day 15) (χ2=4.35, df=1, p<0.04; Wilcoxon test).

Medications

During the double-blind phase, the mean modal doses of medication were 3.8 mg/day (SD=1.8) of risperidone and 6.2 mg/day (SD=2.9) of haloperidol. The mean duration of exposure to medication was 17.1 days (SD=6.5) for the patients who received risperidone plus a mood stabilizer and 16.2 days (SD=6.6) for the patients who received haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer.

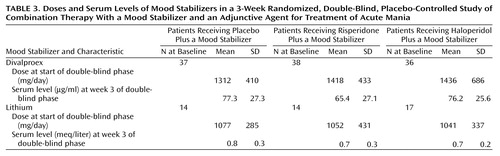

Before entering the trial, 63% of the patients (N=99 of 156) were receiving a mood stabilizer. At the start of the double-blind phase, 71% of the patients (N=111 of 156) received divalproex, and 29% (N=45 of 156) received lithium (Table 3). Blood levels of the medications at week 3 were within the targeted therapeutic range for all groups.

Lorazepam was received by 59% (N=30 of 51) of the patients in the placebo plus mood stabilizer group, 67% (N=35 of 52) in the risperidone plus mood stabilizer group, and 64% (N=34 of 53) in the haloperidol plus mood stabilizer group. Antiparkinsonian medications were received by four (8%) patients in the placebo plus mood stabilizer group, nine (17%) patients in the risperidone plus mood stabilizer group, and 20 (38%) patients in the haloperidol plus mood stabilizer group. The only significant between-group difference was in the use of antiparkinsonian medications between the placebo plus mood stabilizer group and the haloperidol plus mood stabilizer group (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel χ2=12.96, df=1, p<0.001).

Efficacy

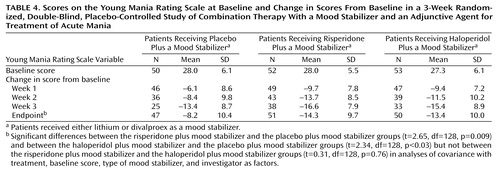

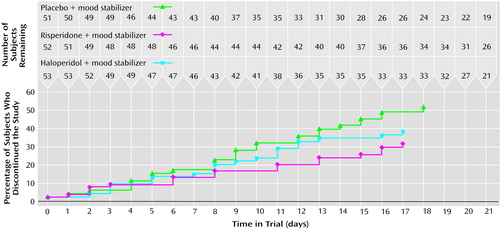

The mean total scores on the Young Mania Rating Scale for the three groups at baseline were comparable (Table 4). Significantly greater improvement in the mean total score on the Young Mania Rating Scale was seen in the risperidone plus mood stabilizer group than in the placebo plus mood stabilizer group at endpoint (–14.3 versus –8.2) (Table 4, Figure 2). In the haloperidol plus mood stabilizer group also, improvement in the mean total score on the Young Mania Rating Scale was significantly greater than in the placebo plus mood stabilizer group at endpoint (–13.4 versus –8.2). Significantly greater improvements in Young Mania Rating Scale total scores over time were seen in the risperidone plus mood stabilizer group and in the haloperidol plus mood stabilizer group than in the placebo plus mood stabilizer group (Figure 2).

An additional analysis compared treatment effects in the 99 patients (63%) who were receiving mood stabilizers when they entered the trial (patients with a “breakthrough episode”) and the 57 patients (37%) who started treatment with mood stabilizers on entering the trial. Among patients who were receiving mood stabilizers at the start of the trial (“breakthrough” patients), the mean total score on the Young Mania Rating Scale (higher scores indicate more severe symptoms) decreased by 7.4 (SD=10.8) in those who received placebo plus a mood stabilizer (N=28), 15.7 (SD=10.6) in those who received risperidone plus a mood stabilizer (N=34), and 14.9 (SD=9.5) in those who received haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer (N=33). Among patients who did not receive mood stabilizers until the start of the trial, the mean total score on the Young Mania Rating Scale decreased by 9.4 (SD=10.1) in the patients who received placebo plus a mood stabilizer (N=19), 11.3 (SD=6.9) in the patients who received risperidone plus a mood stabilizer (N=17), and 10.1 (SD=10.4) in the patients who received haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer (N=17).

A comparison was also made of patients with and without psychotic features at baseline. Of the 156 patients receiving at least one dose of study medication, 61 had psychotic features at baseline and 95 did not. The mean total score on the Young Mania Rating Scale had improved at endpoint with risperidone plus a mood stabilizer and with haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer both in patients with psychotic features (mean change=–15.4, SD=11.2, N=20; and mean change=–16.8, SD=10.1, N=18, respectively) and in patients without psychotic features (mean change=–13.5, SD=8.7, N=31; and mean change=–11.3, SD=9.5, N=32). For the patients who received placebo plus a mood stabilizer, the mean changes in score were –9.3 (SD=11.5) and –7.5 (SD=9.7) in patients with (N=20) and without (N=27) psychotic features, respectively.

The results were also analyzed in subgroups of patients with a manic or a mixed episode. In patients with pure mania, the improvement in the mean total score on the Young Mania Rating Scale was greater with risperidone plus a mood stabilizer (mean change=–14.4, SD=9.4, N=42) or haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer (mean change=–13.7, SD=10.9, N=38) than with placebo plus a mood stabilizer (mean change=–6.6, SD=10.2, N=37). Patients with a mixed episode showed similar improvements with risperidone plus a mood stabilizer (mean change=–13.6, SD=11.3, N=9), haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer (mean change=–12.1, SD=6.3, N=12), and placebo plus a mood stabilizer (mean change=–14.2, SD=9.5, N=10).

CGI severity scores were similar in the treatment groups at baseline, with severity of manic symptoms being rated as marked to moderate in most patients. At endpoint, significant between-group differences were noted on the CGI change scale: ratings of much or very much improved were reported in 30% (N=14 of 47) of the patients who received placebo plus a mood stabilizer, 53% (N=27 of 51) of those who received risperidone plus a mood stabilizer, and 50% (N=25 of 50) of those who received haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer (risperidone plus mood stabilizer versus placebo plus mood stabilizer: Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel χ2=9.7, df=1, p=0.002; and haloperidol plus mood stabilizer versus placebo plus mood stabilizer: Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel χ2=8.9, df=1, p=0.003). An endpoint rating of very much improved was achieved by none of the patients who received placebo plus a mood stabilizer, 25% of the patients who received risperidone plus a mood stabilizer, and 16% of the patients who received haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer.

A comparison of results for patients receiving lithium versus divalproex showed that improvements in the mean total scores on the Young Mania Rating Scale at endpoint were similar in the risperidone plus mood stabilizer group and the haloperidol plus mood stabilizer group (range of mean changes in score: –11.9, SD=9.6, to –14.4, SD=9.9). However, improvement was greater in patients who received placebo plus lithium (mean change=–12.5, SD=10.4) than in those who received placebo plus divalproex (mean change=–6.6, SD=10.1). These differences may not be related to the difference in mood stabilizers because the subjects were stratified in assignment to mood stabilizer group rather than randomly assigned and thus the characteristics of the patients in the two groups may not be comparable.

Adverse Events and Safety

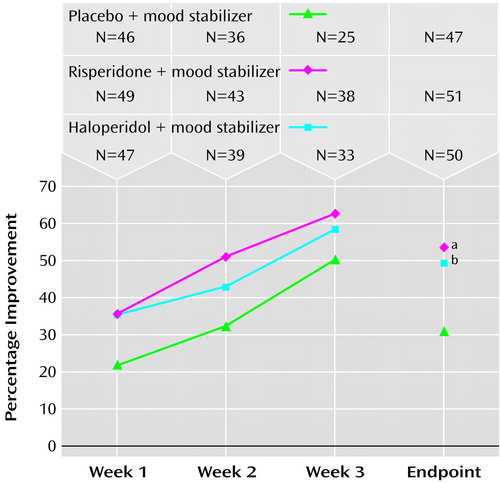

Severity of extrapyramidal symptoms (the mean total score on the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale) was similar in the placebo plus mood stabilizer group and in the risperidone plus mood stabilizer group at endpoint (Figure 3). Among patients who received haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer, however, the mean change in the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale total score from baseline to endpoint and the mean changes to the maximum score were significantly greater than in patients who received placebo plus a mood stabilizer.

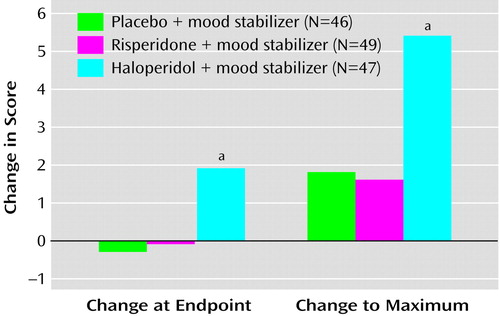

Adverse events were reported by 84% (N=43 of 51), 81% (N=42 of 52), and 92% (N=49 of 53) of patients in the placebo plus mood stabilizer, risperidone plus mood stabilizer, and haloperidol plus mood stabilizer groups, respectively. The most commonly reported adverse events are listed in Table 5. The class of adverse events most commonly reported was related to the central and peripheral nervous systems and included headache, extrapyramidal disorder, and tremor. These adverse events were more frequent in patients who received haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer (N=35; 66%) than in those who received placebo plus a mood stabilizer (N=21; 41%) or risperidone plus a mood stabilizer (N=22; 42%). The greatest between-treatment difference was in extrapyramidal disorder (28%, 13%, and 4% of the patients in the haloperidol plus mood stabilizer, risperidone plus mood stabilizer, and placebo plus mood stabilizer groups, respectively, experienced this adverse event). Antiparkinsonian medications were received by twice as many patients in the haloperidol plus mood stabilizer group (38%) than in the risperidone plus mood stabilizer group (17%). A manic reaction was reported in three patients who received placebo plus a mood stabilizer (6%), three patients who received haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer (6%), and none of the patients who received risperidone plus a mood stabilizer.

The mean weight of patients at baseline was 182.2, 191.9, and 196.9 lb in the placebo plus mood stabilizer, risperidone plus mood stabilizer, and haloperidol plus mood stabilizer groups, respectively. The mean weight change in the three groups at endpoint was 1.1 lb (SD=4.8), 5.3 lb (SD=7.0), and 0.3 lb (SD=5.4), respectively. The weight gain in the risperidone plus mood stabilizer group was significantly greater than in the placebo group (t=2.95, df=105, p<0.004).

No clinically significant changes in vital signs or laboratory values were noted in any group at endpoint. Among the 119 patients (76%) for whom baseline and endpoint ECG data were available, no clinically significant changes were observed in any patient. QTc prolongation (450–500 msec in men and 470–500 msec in women) at endpoint was reported in three patients who received placebo plus a mood stabilizer, three who received risperidone plus a mood stabilizer, and four who received haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer.

Discussion

The addition of risperidone to a mood stabilizer was a safe therapy and was more effective than a mood stabilizer alone in the treatment of acute bipolar mania. Reduction in the severity of mania (Young Mania Rating Scale total score) at endpoint was significantly greater in patients receiving risperidone and a mood stabilizer than in patients receiving a mood stabilizer alone (placebo plus a mood stabilizer). Patients receiving haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer also showed clinical improvement on most efficacy measures, but haloperidol was associated with substantially more extrapyramidal symptoms than risperidone. The overall results are consistent with those from several prior small studies and case reports that suggested antimanic efficacy of atypical antipsychotic medications such as risperidone in the treatment of bipolar disorder, particularly as adjunctive treatment (10, 19–23, 29–32).

The efficacy of risperidone plus a mood stabilizer and haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer was sustained during the 3-week study. The two combinations of medication were associated with significant improvement in the Young Mania Rating Scale total score at endpoint and over time, compared with placebo plus a mood stabilizer. Overall, the performance of the placebo plus mood stabilizer group in this study was comparable to that reported by Bowden et al. for patients receiving lithium or divalproex (5). Thus, the between-group difference appears attributable to the benefit of adjunctive therapy with risperidone rather than a lack of benefit from the mood stabilizer alone.

The present study reports several comparative subanalyses. Risperidone or haloperidol combined with a mood stabilizer was more efficacious than a mood stabilizer alone both in patients with psychosis and in those without psychosis, suggesting that these agents have antimanic properties that are independent of their antipsychotic properties. Among patients with a breakthrough episode (those receiving a mood stabilizer at entry into the trial), improvement was more robust with risperidone plus a mood stabilizer or haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer than with placebo plus a mood stabilizer (mean changes in the Young Mania Rating Scale total score were –15.7, –14.9, and –7.4, respectively). Similarly, among patients with a pure manic episode, a substantially better therapeutic effect was observed in the risperidone plus mood stabilizer group (mean change=–14.4, SD=9.4) and the haloperidol plus mood stabilizer group (mean change=–13.7, SD=10.9) than in the placebo plus mood stabilizer group (mean change=–6.6, SD=10.2). Among subjects with mixed episodes, similar improvements were observed in all three conditions.

We found no evidence of exacerbation of manic symptoms associated with risperidone. Earlier reports have suggested an association between risperidone use and subsequent manic or hypomanic episodes (33–39). Most of these reports were of isolated cases or series influenced by a variety of confounding factors (39). In most cases, patients who developed mania were not taking a primary mood stabilizer (i.e., lithium or divalproex) (40).

Treatment was generally well tolerated in all three groups, with one exception: severity of extrapyramidal symptoms (mean Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale total score) at endpoint was significantly greater in patients receiving haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer than in patients receiving placebo plus a mood stabilizer, while differences between the placebo plus mood stabilizer and the risperidone plus mood stabilizer groups were not significant (Figure 3). Among patients receiving haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer, 28% reported extrapyramidal symptoms and 38% required antiparkinsonian medications during the trial. These rates were greater than those seen in the risperidone plus mood stabilizer group (13% and 17%, respectively), even at the relatively low mean modal dose of haloperidol (mean=6.2 mg/day, SD=2.9) (risperidone mean=3.8 mg/day, SD=1.8).

The weight gain observed in the risperidone plus mood stabilizer group was similar to that in previous studies with risperidone, but over a shorter period of time. Data from the 10-week extension study (N=85) indicated a plateau effect on weight gain. After 10 weeks’ treatment with risperidone plus a mood stabilizer, mean weight gains were 3.1 lb (SD=7.0) in patients who had received placebo plus a mood stabilizer in the 3-week study, 2.6 lb (SD=8.3) in patients who had received risperidone plus a mood stabilizer and 2.9 lb (SD=7.2) in patients who had received haloperidol plus a mood stabilizer.

The study had several limitations. For ethical reasons, patients were permitted to leave the double-blind phase and enter the open-label phase any time after 7 days from the start of the double-blind phase. This did not have a substantial impact on the course of the study: only four patients in the placebo plus mood stabilizer group, four in the risperidone plus mood stabilizer group, and one in the haloperidol plus mood stabilizer group entered the open-label phase before completing the double-blind phase. Patients who were and were not receiving a mood stabilizer were allowed to enter the study: 37% initiated treatment with a mood stabilizer at the start of the study, while 63% were already receiving a mood stabilizer. We stratified patients based on their use of mood stabilizers at baseline to improve the generalizability of the results to the population of patients seen in routine practice.

Although the serum levels of mood stabilizers in this study were low relative to those reported by Bowden et al. (5) for monotherapy in similar patients, several lines of evidence have suggested that the levels were within an acceptable therapeutic range. The placebo plus mood stabilizer group responded as well in this study as those receiving lithium or valproate monotherapy in the previous study (5), and bloods levels of medication in this study were within the range reported to be effective.

The combination therapy design of this study allowed enrollment of more severely ill manic patients with bipolar I disorder than have generally been recruited for monotherapy placebo studies. Patients who might have declined participation in a study that offered an equal chance of receiving monotherapy active drug or placebo understood that they would continue, or start taking, lithium or divalproex. This design advantage is also consistent with practice guidelines, which suggest combination regimens for more severely ill patients (3).

This study does not conclusively address whether risperidone is a mood stabilizer. A mood stabilizer has been defined as “a drug that alleviates the frequency, intensity, or both, of manic, hypomanic, depressive, or mixed episodes in patients with bipolar disorder, and that does not increase the frequency or severity of any phase of bipolar disorder” (41). The current results are consistent with this definition and support the need for additional longer-term studies.

The results demonstrate that the combination of risperidone with a mood stabilizer was superior to a mood stabilizer alone for the rapid reduction of manic symptoms. The combination may also be associated with the need for lower blood levels of the mood stabilizer, thus diminishing dose-related side effects associated with these agents. The combined use of risperidone and a mood stabilizer was well tolerated in these acutely manic patients.

|

|

|

|

|

Received Nov. 15, 2000; revisions received June 15 and Nov. 26, 2001; accepted March 5, 2002. From the Bipolar Research Program, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Johnson and Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development, Titusville, N.J.; the Department of Psychiatry, Cambridge Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston; and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Address reprint requests to Dr. Sachs, 50 Staniford St., Suite 580, Boston, MA 02114; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by the Janssen Research Foundation.

Figure 1. Time to Study Discontinuation in a 3-Week Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Combination Therapy With a Mood Stabilizer and an Adjunctive Agent for Treatment of Acute Maniaa

aFor patients who discontinued the double-blind study to enter the open-label study, discontinuation was the first date of open-label enrollment. For patients who discontinued and did not enter the open-label study, discontinuation was the last date medication was administered in the double-blind study. Patients who completed 19 days or more of the double-blind study were considered completers.

Figure 2. Mean Percentage Improvement in the Young Mania Rating Scale Total Score in a 3-Week Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Combination Therapy With a Mood Stabilizer and an Adjunctive Agent for Treatment of Acute Mania

aSignificant difference between the risperidone plus mood stabilizer and the placebo plus mood stabilizer groups (t=–2.64, df=353, p<0.009, repeated-measures analysis).

bSignificant difference between the haloperidol plus mood stabilizer and the placebo plus mood stabilizer groups (t=–2.16, df=353, p<0.04, repeated-measures analysis).

Figure 3. Mean Change in Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale Total Score in a 3-Week Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Combination Therapy With a Mood Stabilizer and an Adjunctive Agent for Treatment of Acute Mania

aSignificant difference between the haloperidol plus mood stabilizer and the placebo plus mood stabilizer groups (χ2=4.60, df=1, p<0.05, Van Elteren test controlling for investigator and mood stabilizer).

1. Jamison KR: Suicide and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61(suppl 9):47-51Google Scholar

2. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151(Dec suppl)Google Scholar

3. Frances A, Docherty JP, Kahn DA: The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: Treatment of Bipolar Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 12A)Google Scholar

4. Janicak PG, Newman RH, Davis JM: Advances in the treatment of mania and related disorders. Psychiatr Annals 1992; 22:92-103Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Bowden CL, Brugger AM, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Janicak PG, Dilsaver PF, Davis JM, Rush AJ, Small JG: Efficacy of divalproex vs lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. JAMA 1994; 271:918-924Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Gelenberg AJ, Kane JM, Keller MB, Lavori P, Rosenbaum JF, Cole K, Lavelle J: Comparison of standard and low serum levels of lithium for maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:1489-1493Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Gelenberg AJ, Hopkins HS: Antipsychotics in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 9):49-52Google Scholar

8. Prien RF, Caffey EM, Klett CJ: A comparison of lithium carbonate and chlorpromazine in the treatment of acute mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1972; 26:146-153Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Janicak PG, Davis JM, Preskorn SH, Ayd FJ Jr: Principles and Practice of Psychopharmacotherapy, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Williams & Wilkins, 1997, pp 389-473Google Scholar

10. Ghaemi SN, Goodwin FK: Use of atypical antipsychotic agents in bipolar and schizoaffective disorders: review of the empirical literature. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1999; 19:354-361Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Segal J, Berk M, Brook S: Risperidone compared with both lithium and haloperidol in mania: double-blind randomized controlled trial. Clin Neuropharmacol 1998; 21:176-180Medline, Google Scholar

12. Tohen M, Sanger TM, McElroy SL, Tollefson GD, Chengappa KNR, Daniel DG, Petty F, Centorrino F, Wang R, Grundy SL, Greaney MG, Jacobs TG, David SR, Toma V (Olanzapine HGEH Study Group): Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:702-709Abstract, Google Scholar

13. Tohen M, Jacobs TG, Grundy SL, McElroy SL, Banov MC, Janicak PG, Sanger T, Risser R, Zhang F, Toma V, Tollefsen GD, Breier A: Efficacy of olanzapine in acute bipolar mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:841-849Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Freeman MP, Stoll AL: Mood stabilizer combinations: a review of safety and efficacy. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:12-21Link, Google Scholar

15. Pande AC, Crockatt JG, Janney CA, Werth JL, Tsaroucha G: Gabapentin in bipolar disorder: a placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive therapy. Bipolar Disord 2000; 2:249-255Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Tohen M, Zarate CA: Antipsychotic agents and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 1):38-48Google Scholar

17. Muller-Oerlinghausen B, Retzow A, Henn FA, Giedke H, Walden J: Valproate as an adjunct to neuroleptic medication for the treatment of acute episodes of mania: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 20:195-203Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Zarate CA: Antipsychotic drug side effect issues in bipolar manic patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 61(suppl 8):52-61Google Scholar

19. Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Baldassano CF, Truman CJ: Acute treatment of bipolar disorder with adjunctive risperidone in outpatients. Can J Psychiatry 1997; 42:196-199Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS: Long-term risperidone treatment in bipolar disorder: 6-month follow up. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 12:333-338Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Jacobsen FM: Risperidone in the treatment of affective illness and obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:423-429Medline, Google Scholar

22. Vieta E, Gasto C, Colom F, Martinez A, Otero A, Vallejo J: Treatment of refractory rapid cycling bipolar disorder with risperidone. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1998; 18:172-174Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Guille C, Sachs GS, Ghaemi SN: A naturalistic comparison of clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine in the treatment of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:638-642Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA: A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:429-435Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 218-222Google Scholar

26. Chouinard G, Ross-Chouinard A, Annable L, Jones BD: Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (abstract). Can J Neurol Sci 1980; 7:233Google Scholar

27. Gehan EA: A generalized Wilcoxon test for comparing arbitrarily single-censored samples. Biometrika 1965; 52:203-223Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Van Elteren PH: On the combination of independent two-sample tests of Wilcoxon. Bull Int Inst Stat 1960; 7:351-361Google Scholar

29. Frye MA, Ketter TA, Altshuler LL, Denicoff K, Dunn RT, Kimbrell TSA, Cora-Locatelli G, Post RM: Clozapine in bipolar disorder: treatment implications for other atypical antipsychotics. J Affect Disord 1998; 48:91-104Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Green AI, Tohen M, Patel JK, Banov M, DuRand C, Berman I, Chang H, Zarate C Jr, Posener J, Lee H, Dawson R, Richards C, Cole JO, Schatzberg AF: Clozapine in the treatment of refractory psychotic mania. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:982-986Link, Google Scholar

31. Suppes T, Webb A, Paul B, Carmody T, Kraemer H, Rush AJ: Clinical outcome in a randomized 1-year trial of clozapine versus treatment as usual for patients with treatment-resistant illness and a history of mania. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1164-1169Abstract, Google Scholar

32. Zarate CA Jr, Tohen M, Banov MD, Weiss MK, Cole JO: Is clozapine a mood stabilizer? J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:108-112Medline, Google Scholar

33. Barkin JS, Pais VM: Induction of mania by risperidone resistant to mood stabilizers. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 17:57-58Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Diaz SF: Mania associated with risperidone use. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57:41-42Medline, Google Scholar

35. Dwight MM, Keck PE, Stanton SP, Strakowski SM, McElroy SL: Antidepressant activity and mania associated with risperidone treatment of schizoaffective disorder. Lancet 1994; 344:554-555Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Koek RJ, Kessler CC: Probable induction of mania by risperidone. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57:174-175Medline, Google Scholar

37. O’Croinin F, Zibin T, Holt L: Re: hypomania associated with risperidone (letter). Can J Psychiatry 1995; 40:51Medline, Google Scholar

38. Schnierow BJ, Graeber DA: Manic symptoms associated with initiation of risperidone (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1235-1236Link, Google Scholar

39. Tomlinson WC: Risperidone and mania (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:132-133Medline, Google Scholar

40. Aubry J-M, Simon A, Bertschy G: Possible induction of mania and hypomania by olanzapine or risperidone: a critical review of reported cases. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:649-655Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Bowden CL: Treatment of bipolar disorder. Curr Rev Mood Anxiety Disord 1997; 1:167-176Google Scholar