Combined Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy as Maintenance Treatment for Late-Life Depression: Effects on Social Adjustment

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the effects of maintenance treatment for late-life depression on social adjustment. The authors hypothesized that elderly patients recovering from depression would have better social adjustment with medication and interpersonal psychotherapy than with medication or psychotherapy alone. METHOD: Patients aged 60 and older recovering from recurrent major depression were randomly assigned to one of four treatments: nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy, nortriptyline and clinic visits, placebo and psychotherapy, or placebo and clinic visits. The Social Adjustment Scale was administered every 3 months until illness recurrence. Combined treatment was compared to monotherapy on scores over 1 year among patients who remained in recovery (N=49). RESULTS: Patients receiving nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy maintained social adjustment, which declined in those receiving monotherapy. CONCLUSIONS: Treatment of late-life depression with nortriptyline and psychotherapy is more likely to maintain social adjustment than treatment with either alone. Combination therapy improves not only duration but quality of wellness.

Major depressive illness causes not only mood symptoms but also impairments in functional abilities, such as social adjustment. As a result, social function has been used as a measure of depression outcome (1), to measure quality of recovery with treatment. We have found that elderly subjects successfully treated for major depression with nortriptyline and interpersonal therapy showed large improvements in social adjustment (2).

The present study examined the social adjustment of these subjects during maintenance treatment for late-life depression. We have previously shown that these individuals were more likely to stay in recovery if they were maintained with combined medication and interpersonal psychotherapy than with nortriptyline alone, interpersonal psychotherapy and placebo, or placebo alone (3). We hypothesized that subjects who stayed in recovery would have better social adjustment if they received combined maintenance treatment, as compared to monotherapy.

Method

Subjects were required to be aged 60 and older, with recurrent, nonpsychotic nonbipolar major depression and a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (4) score of 17 or greater. They were recruited from clinical referrals and the community. The subjects had no unstable medical conditions or contraindications to nortriptyline and were required to score 27 or higher on the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (5). Written informed consent was obtained after a full description of the study was presented to the subjects.

The subjects received open acute treatment with combined nortriptyline and weekly interpersonal psychotherapy to achieve remission of depressive symptoms (6). Remitted subjects entered a 16-week continuation phase of open-label medication treatment and twice-monthly interpersonal psychotherapy. The subjects who completed continuation treatment with 3 consecutive weeks of Hamilton depression scale scores of 10 or lower were randomly assigned to maintenance treatment with nortriptyline and monthly interpersonal psychotherapy, nortriptyline plus medication clinic visits (no psychotherapy), placebo plus interpersonal psychotherapy, or placebo plus medication clinic visits. The subjects remained in maintenance treatment for 36 months or until a they experienced a recurrence of major depression, whichever occurred first. We limited the present analysis to subjects still in recovery after 12 months, because further recurrences in the subsequent 24 months greatly reduced the number of observations. Because most subjects receiving placebo and visiting the medication clinic had a recurrence of depression within the first 12 months, only the groups receiving combination therapy and monotherapy were compared in the present study (N=49).

We administered the Social Adjustment Scale (7) every 3 months during maintenance treatment. The Social Adjustment Scale examines four domains of functioning: performance (e.g., impaired performance, disinterest, and lost time), interpersonal behavior (e.g., reticence, hypersensitivity, and dependency), friction (e.g., tension or quarreling), and satisfaction (e.g., loneliness, inadequacy, and disinterest). Scores on the Social Adjustment Scale, which was developed as an outcome measure in studies of medication and psychotherapy in depression, were expressed as a value of 1–5, with higher scores indicating poorer social adjustment.

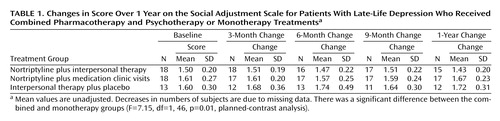

We evaluated the hypothesis that subjects receiving combined treatment would maintain Social Adjustment Scale scores, while the monotherapy groups would worsen over time. We used planned-contrast analysis (8) within a repeated-measures mixed model. (The planned-contrast approach allows a hypothesis to be precisely tested, unlike the omnibus F from analysis of variance, which tests only whether—but not exactly how—the groups differed over time.) The analysis controlled for residual depressive symptoms. The repeated-measures mixed-model analysis, with restricted maximum-likelihood estimation, used compound symmetry for the variance/covariance structure. The subjects’ mean scores on the four domains of the Social Adjustment Scale were also examined with planned contrasts. Additionally, scores on the Social Adjustment Scale are presented in Figure 1 as the mean percentage change in group scores.

Results

After 1 year of maintenance treatment, 49 subjects remained in recovery: 18 in the combined group, 18 in the nortriptyline group, and 13 in the interpersonal psychotherapy group. The three groups did not differ significantly in terms of age (all groups: mean=66.8 years, SD=4.7), the number of women (71% for all groups), the number of Caucasians (96% for all groups), years of education, whether or not they were employed, the number of previous major depressive episodes, or Hamilton depression scale scores at the start of maintenance treatment.

Mean scores on the Social Adjustment Scale improved in the combined therapy group, while the scores of the subjects receiving either type of monotherapy declined (F=7.15, df=1, 46, p=0.01, planned-contrast analysis) (Table 1). The effect size (9)—i.e., the degree to which the hypothesis, as embodied in the planned contrast, fit the data—was modest (r=0.18). (The effect size is the correlation between the contrast weights and the observed means, which were obtained from the planned-contrast analysis, and is interpreted as is any other Pearson’s r; i.e., the larger the r value, the better the planned contrast describes the specific pattern of differences among the means.)

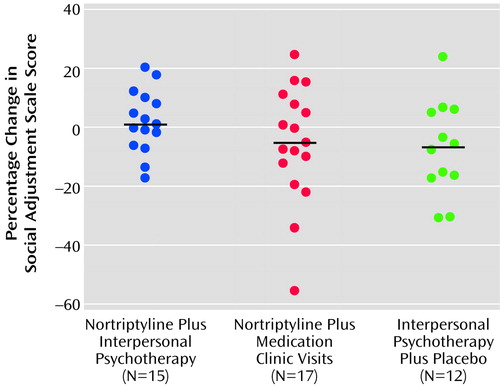

Figure 1 illustrates the clinical significance of the effect, comparing percentage changes in scores on the Social Adjustment Scale over the 1-year period among the combined therapy and the two monotherapy groups. Scores improved in the combined group, while they declined in the nortriptyline group and in the interpersonal psychotherapy group.

Within the four domains of the Social Adjustment Scale, we found a significant difference among the groups in the friction domain (F=4.71, df=1, 46, p=0.04, r=0.15), indicating stable mean scores in the combined group and worsening scores in the monotherapy groups over time. Effects were nonsignificant for the performance domain (F=3.75, df=1, 46, p=0.06, r=0.13), the interpersonal domain (F=2.63, df=1, 46, p=0.11, r=0.11), and the satisfaction domain (F=1.66, df=1, 46, p=0.20, r=0.09).

We also compared scores on the Social Adjustment Scale for the combined treatment group to scores for each of the monotherapy groups separately. Planned-contrast analysis yielded significant results for combined treatment versus nortriptyline monotherapy (F=6.55, df=1, 34, p<0.02, r=0.20) and for combined treatment versus interpersonal psychotherapy (F=7.21, df=1, 29, p<0.02, r=0.23).

Finally, we determined whether decline in social functioning during maintenance treatment predicted future recurrence. We compared the rate of recurrence across all three treatment groups in years 2–3 after maintenance treatment was begun on the basis of whether they maintained (or improved) their scores on the Social Adjustment Scale or whether scores declined during the year of maintenance therapy. Only one (5.3%) of 19 subjects who maintained his or her scores on the Social Adjustment Scale had a recurrence of depression in years 2–3, while of the 19 subjects who had a decline in scores on the Social Adjustment Scale during 1 year of therapy, five (26.3%) had a recurrence.

Discussion

We observed that elderly subjects in maintenance treatment for recurrent major depression maintained treatment-attributable improvements in social adjustment best with combined interpersonal psychotherapy and nortriptyline. To our knowledge, this is the first report concerning social function in a controlled randomized study of elderly patients receiving maintenance treatment for late-life depression. A prior report by our group (3) showed the advantages of combining medication and interpersonal psychotherapy in the maintenance treatment of depressed elderly patients in prolonging recovery. The present study shows that combination treatment enhances not only the length but also the quality of recovery.

Our results are comparable to those of a previous study in younger adults in maintenance treatment for depression (1), which found significant improvements in social adjustment attributable to combined interpersonal psychotherapy and maintenance medication. In contrast to that study, we did not find significant social adjustment improvements during maintenance treatment with combined therapy; however, such therapy provided better retention of the significant gains that had already been made during acute and continuation treatment. The greatest effect was in the domain of interpersonal conflict. We have previously observed that the three most common foci of interpersonal psychotherapy in acute treatment were role transitions, interpersonal disputes, and abnormal grief (10). That observation, together with the present study, suggests pathways by which interpersonal psychotherapy may work with medication to produce and maintain better social functioning in individuals with late-life depression.

|

Received Oct. 11, 2000; revisions received Feb. 13, May 2, and Aug. 13, 2001; accepted Sept. 13, 2001. From the Intervention Research Centers in Late-Life and Mid-Life Mood Disorders, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pa. Address reprint requests to Dr. Reynolds, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, 3811 O’Hara St., Rm. E1135, Pittsburgh, PA 15213; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants MH-52247, MH-30915, MH-00295, MH-43832, MH-37869, and MH-19986.

Figure 1. Percentage Changes in Score Over 1 Year on the Social Adjustment Scale for Patients With Late-Life Depression Who Received Combined Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy or Monotherapy Treatmentsa

aPercentages were adjusted for depressive symptoms. Mean values are represented by the black horizontal lines.

1. Weissman MM, Klerman GL, Paykel ES, Prusoff B, Hanson B: Treatment effects on the social adjustment of depressed patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974; 30:771-778Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Lenze EJ, Miller MD, Dew MA, Martire LM, Mulsant BH, Begley AE, Schulz R, Frank E, Reynolds CF: Subjective health measures as predictors and outcomes of acute treatment for late-life depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry (in press)Google Scholar

3. Reynolds CF, Frank E, Perel JM, Imber SD, Cornes C, Miller MD, Mazumdar S, Houck PR, Dew MA, Stack JA, Pollock BG, Kupfer DJ: Nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy as maintenance therapies for recurrent major depression: a randomized controlled trial in patients older than 59 years. JAMA 1999; 281:39-45Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56-62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189-198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Little JT, Reynolds CF III, Dew MA, Frank E, Begley AE, Miller MD, Cornes C, Mazumdar S, Perel JM, Kupfer DJ: How common is resistance to treatment in recurrent, nonpsychotic geriatric depression? Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1035-1038Link, Google Scholar

7. Weissman MM, Kasl SV, Klerman GL: Follow-up of depressed women after maintenance treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1976; 133:757-760Link, Google Scholar

8. Rosenthal R, Rosnow RL: Contrast Analysis: Focused Comparisons in the Analysis of Variance. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1985Google Scholar

9. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988Google Scholar

10. Wolfson LK, Miller M, Houck PR, Ehrenpreis L, Stack JA, Frank E, Cornes C, Mazumdar S, Kupfer DJ, Reynolds CF: Foci of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) in depressed elders: clinical and outcome correlates in a combined IPT/nortriptyline protocol. Psychotherapy Res 1997; 7:45-55Crossref, Google Scholar