Differential Evolution of Cognitive Impairment in Nondemented Older Persons: Results From the Kungsholmen Project

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study was a prospective, population-based examination of the evolution of cognitive impairment, no dementia (CIND). METHOD: Subjects 75 years old or older living in Stockholm were assessed at baseline and 3 and 6 years later. The severity of CIND was based on age- and education-specific norms on the Mini-Mental State Examination and was classified as mild (N=212), moderate (N=96), or severe (N=57). Mortality, progression to dementia (DSM-III-R), cognitive stability, and cognitive improvement were studied as main outcomes. RESULTS: Of the individuals with mild CIND, 63 (34%) died, 65 (35%) progressed to dementia, 21 (11%) remained stable, and 46 (25%) improved between baseline and first follow-up. The relative risks of progressing to dementia by first follow-up in the subjects with mild, moderate, and severe CIND were 3.6, 5.4, and 7.0, respectively. The relative risk of death decreased with increasing severity of impairment. Individuals who improved at first follow-up did not have a significantly higher risk of later progressing to dementia than subjects who had never been impaired (relative risk=1.4). The absence of a subjective memory complaint predicted improvement (odds ratio=5.4). CONCLUSIONS: CIND is a heterogeneous condition: similar proportions of subjects progress to dementia, death, and cognitive improvement over 3 years. There is no increased future risk of progressing to dementia in CIND subjects who improve during that period.

Cognitive impairment, no dementia (CIND) can be defined as a state characterized by lower cognitive performance than would be expected given the age and educational attainment of the person (1). Recently, Ritchie and Touchon (2) reviewed the different classifications that have been used to describe subjects who are cognitively impaired but have no dementia diagnosis, and those authors found a large variation in concepts, inclusion criteria, and definitions. Irrespective of the different criteria, most studies have shown that these individuals have a more rapid rate of cognitive decline than unimpaired persons (3) and a high risk of progressing to dementia (4–14). Different progression rates have been reported, depending on the definition of impairment and the length of follow-up: 12%–38% over 1 year (4, 7), 36% over 2 years (12), 18% over 3 years (13), and 42% over 5 years (14).

The increasing interest in this topic is partly due to the fact that subjects with CIND may be a potential target population for pharmacological treatment to prevent or delay the onset of dementia (15, 16). However, some studies (6–14, 17, 18) have shown that a substantial number of subjects with CIND remain stable or improve in cognitive functioning over time. In a Finnish study (17), 22% of the subjects with CIND improved after 3 years. Similarly, Daly et al. (18) reported an improvement in 15%, with an additional 29% remaining stable after 3 years. Still, it remains unknown whether the observed improvement is stable over time.

We examined the progression of CIND over 3 and 6 years in a population-based longitudinal study. The aim was to characterize the evolution of CIND. Specifically, we sought to examine whether progression to dementia or improvement is time dependent and to determine the long-term evolution of the subjects with CIND who do not progress to dementia in the first 3 years.

Method

The data were taken from the Kungsholmen Project, a longitudinal study on aging and dementia that was initiated on Oct. 1, 1987, and included all inhabitants aged 75 and older in the Kungsholmen district of Stockholm. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. Three follow-up evaluations, about 3 years apart from each other, have been carried out so far.

Study Population

The study population consisted of the dementia-free cohort identified at baseline in the Kungsholmen Project (19, 20). At baseline, current dementia cases were identified through a two-phase study design and diagnosed by specialists according to DSM-III-R criteria. Of the 1,700 participants, 225 subjects were classified as having definite or questionable dementia, and 1,475 were classified as nondemented. In the present study, 31 subjects were excluded because of low cognitive performance at baseline, defined as a score of less than 20 on the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (21), and nine persons were excluded because of unknown educational background or age over 95 years. The remaining 1,435 nondemented subjects, with MMSE scores of 20 or higher and aged 75 to 95 years, constituted the study population.

Definition of CIND

CIND was defined on the basis of MMSE performance. The effects of age and education on MMSE score were taken into account by stratifying performance into age- and education-specific groups (22). The strata were chosen to minimize cohort effects and to allow sufficient numbers of subjects in each group. On the basis of previous reports (19), two education categories were used, low (2–7 years) and high (8 years or more), and seven age strata were defined (22).

Three different levels of CIND were examined. CIND was classified as mild if the subject scored 1 standard deviation below the age- and education-specific mean on the MMSE. Moderate was defined as 1.5 standard deviations below the mean, and severe was defined as 2 standard deviations below the mean. Cutoff points on the MMSE increased with increasing severity of CIND, decreased with age, and were higher for persons with more years of education. Cutoff levels for mild CIND ranged from 23 for persons aged 90–95 with low education levels to 26 for individuals with high education levels in the 75–76 age category. Cutoff scores for moderate CIND ranged from 22 for subjects aged 90–95 with low education levels to 25 for persons with high education levels aged 75–76. For severe CIND the cutoffs ranged from 21 for persons aged 90–95 with low education levels to 25 for individuals with high education levels in the 75–76 age group. Persons scoring lower than these cutoff points on the MMSE were classified as impaired.

Baseline Independent Variables

Data on age, education, and sex were collected at baseline. Education was assessed as the maximum level achieved.

History of cerebrovascular and coronary disease and malignancy was derived from the Computerized Stockholm Inpatient Registry System, in which admission and discharge diagnoses from all hospitals in Stockholm are recorded, as previously described (23). Diseases were diagnosed according to ICD-8: codes 430–438 for cerebrovascular disease, 410 to 414 for coronary disease, and 140 to 208 and 230 to 239 for malignancy. Drug use was ascertained through interviews and by inspecting medicine bottles, prescriptions, and medicine lists (24). Psychotropic drugs included neuroleptics, benzodiazepines, other tranquilizers and hypnotics, and antidepressants.

The presence of current depressive symptoms was defined as the subjective report of often feeling lonely or often being in a low mood. Subjective memory was assessed by self-reported memory complaints at baseline.

Outcomes

Death, progression to dementia, cognitive stability, and cognitive improvement were studied as main outcomes. All participating survivors underwent an extensive clinical examination at follow-up that was similar to the protocol used at baseline. At the first follow-up examination, 3.4 years (SD=0.6) after baseline, 170 subjects (12%) refused to participate or had moved. Fifty-six (6%) of the surviving participants (N=974) at first follow-up dropped out before the second follow-up, which occurred 6.7 years (SD=0.5) after baseline.

Death reports were collected monthly from official registers. Subjects with a dementia diagnosis were included in this outcome category. Seventeen subjects with a dementia diagnosis died between baseline and the first follow-up, and there were 18 such cases between the first and second follow-ups.

Dementia at follow-up was diagnosed as definite (all DSM-III-R criteria fulfilled) or questionable (all but one DSM-III-R criteria fulfilled). A double diagnostic procedure was adopted (19, 20). The preliminary diagnosis was made by the examining physician and independently reviewed by a specialist. In the case of agreement, the diagnosis was accepted; otherwise, a second specialist was consulted and a final diagnosis was reached. Dementia diagnoses for deceased subjects were made by consulting hospital medical records and death certificates and using the same double diagnostic procedure. When only the death certificate or discharge diagnosis was available, the reported diagnosis was accepted.

The people with baseline CIND who still fulfilled the criteria for CIND at follow-up but did not progress to dementia were defined as stable. The same age- and education-specific cutoffs in MMSE scores used at baseline were used at follow-up. Participants who had CIND at baseline but whose follow-up MMSE scores rose above the age- and education-specific cutoff for CIND were categorized as cognitively improved.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out by using SPSS (25). Two-tailed chi-square or independent Student’s t tests were used for assessing the proportional and mean differences between persons with CIND and persons who were cognitively unimpaired at baseline.

All outcomes were studied in relation to the three levels of CIND. In studying the evolution of CIND, two time periods were examined: the interval between baseline and the first follow-up (3 years) and the interval between baseline and the second follow-up (6 years). The evolution of CIND was described by using three measures. First, the proportions of death, dementia, cognitive stability, and cognitive improvement were assessed at both follow-ups. Dead subjects with a dementia diagnosis were included in both the dementia and death categories; thus, the percentages reported in the tables do not total 100%.

Second, the relative risks and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of death and dementia were estimated from hazard ratios derived from Cox regression models. The statistical significance of coefficients was tested with Wald’s chi-square statistic (26). Time of observation was the period between baseline and follow-up assessment, with onset of dementia assumed as being midway between the baseline examination and the date of the follow-up examination or death. Adjustments for age, sex, and education were routinely made by introducing these variables in the different regression models.

Third, in subjects with mild baseline CIND, odds ratios from logistic regression models, with 95% CIs, were used to detect predictors of cognitive improvement at first follow-up, compared to progression to dementia. Sociodemographic characteristics, presence of other somatic diseases, presence of depressive symptoms, and subjective memory complaint at baseline were included as predictors. Statistical significance was tested by using the Wald’s chi-square statistic (26). In this case too, age, sex, and education were statistically controlled.

Results

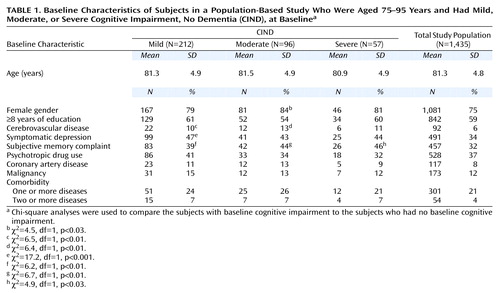

Of the 1,435 subjects in the baseline study population, 75% were female (Table 1). According to the CIND cutoff points used, 212 subjects were classified as having mild CIND at baseline and 1,223 were unimpaired. Ninety-six had moderate CIND and 1,339 were unimpaired at baseline according to this definition. Fifty-seven had severe CIND and 1,378 were unimpaired at this level of severity at baseline.

Table 1 shows that the subjects with CIND reported more subjective memory complaints at baseline than unimpaired individuals across all severity levels. The subjects with mild CIND were also more likely to have symptomatic depression, and individuals with mild or moderate CIND were more likely to have cerebrovascular disease than unimpaired subjects.

The analysis of the dropouts (12% at first follow-up and 6% at second follow-up) revealed that the proportion of those who refused to be reevaluated did not differ significantly between the subjects with CIND and those who were unimpaired. Further, there were no significant differences between participants and dropouts in level of education or sex. However, those who refused to participate were significantly younger (χ2=–2.6, df=1433, p<0.01) than the participants.

3-Year Outcome

The relative risks and proportion of deaths between baseline and first follow-up in subjects with CIND are shown in Table 2. Subjects with mild and moderate CIND had a statistically higher risk of dying in 3 years than the unimpaired subjects. However, subjects with severe CIND had no excess risk of dying. The relative risks of death decreased slightly with increasing severity of CIND, but there was no reliable difference among the three CIND groupings.

The risk of progressing to dementia in subjects with mild, moderate, and severe CIND was three, five, and seven times as high, respectively, as the risk for unimpaired subjects (Table 2). As the severity of CIND increased, the proportion of subjects that remained stable over 3 years decreased. In contrast, approximately one-quarter of the subjects with baseline CIND improved at first follow-up across all three severity levels.

6-Year Outcome

The relative risks of death over 6 years of follow-up were similar to the risks seen across the first 3-year follow-up. Compared to unimpaired persons, subjects with mild CIND had a higher risk of death (relative risk=1.8, 95% CI=1.5–2.2) (χ2=13.0, df=1, p<0.001) after adjustment for age, sex, and education. The relative risks for persons with moderate CIND were smaller than those seen for mild CIND (relative risk=1.6, 95% CI=1.2–2.1) (χ2=5.6, df=1, p<0.02). Compared to unimpaired persons, individuals with severe CIND did not have a significantly higher risk of death (relative risk=1.2, 95% CI=0.8–1.8) (χ2=1.3, df=1, p<0.30).

The relative risks of dementia observed at the 6-year follow-up among the CIND participants were all lower than those for dementia observed at 3 years, irrespective of the initial severity of CIND. The risk of progressing to dementia over 6 years was higher than for unimpaired persons among the participants with mild CIND (relative risk=1.7, 95% CI=1.3–2.2) (χ2=11.4, df=1, p<0.001), among those with moderate CIND (relative risk=1.5, 95% CI=1.0–2.1) (χ2=4.3, df=1, p<0.04), and among those with severe CIND (relative risk=1.8, 95% CI=1.2–2.7) (χ2=7.8, df=1, p<0.005). Of the subjects who progressed to dementia between baseline and second follow-up, 84% of those with mild CIND, 88% of those with moderate CIND, and 89% of those with severe CIND already had the diagnosis at first follow-up.

The proportion of subjects remaining stable at second follow-up was lower than the proportion at first follow-up. Only 7% of the subjects with mild CIND, 1% of those with moderate CIND, and 2% of those with severe CIND remained cognitively impaired but not demented. Improvement at second follow-up was seen in 12% of the subjects with mild CIND, 15% of those with moderate CIND, and 17% of those with severe CIND.

Improvement From CIND

We further examined progression to dementia and death between the first and second follow-ups by comparing the subjects with improvement from CIND to those who had never been impaired. Because of insufficient numbers of subjects, we could examine improvement only in the subjects with mild CIND. Of the 46 improvers with mild CIND, 27 (59%) increased by three or more points on the MMSE at first follow-up. Table 3 shows the relative risks of death and progression to dementia between the first and second follow-up examinations. The improvers did not have a significantly higher risk of dying or progressing to dementia than subjects who had never been classified as cognitively impaired.

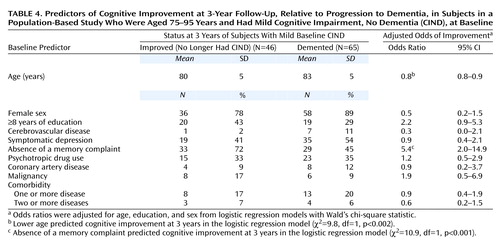

Using logistic regression analysis with a 95% CI, and Wald’s chi-square statistic (26) to test significance, we examined baseline predictors of cognitive improvement, compared to progression to dementia, in subjects with mild CIND (Table 4). Most of the factors did not reveal any significant differences, which may reflect low statistical power. However, the absence of a subjective memory complaint at baseline emerged as a statistically significant predictor of improvement.

To confirm the results concerning improvement after 3 years, we examined incident cases of CIND. Specifically, we sought to eliminate the possibility that the improvement observed in a sizable number of subjects with CIND may reflect exposure to the MMSE testing situation. There were 82 incident cases of CIND, i.e., subjects without impairment at baseline who had developed mild CIND at first follow-up, according to the same cutoffs that were defined at baseline. At the second follow-up, 78 of the subjects with incident CIND were evaluated. Between the first and second follow-ups, 25 (32%) died, 29 (37%) progressed to dementia, 15 (19%) remained stable, and 15 (19%) improved. In six (8%) of the cases, the subject died but also had a dementia diagnosis obtained from death certificates and medical records. The mean age of the subjects with mild incident CIND at the first follow-up examination was 84.9 years (SD=43.3) compared to the mean age of the subjects with mild baseline CIND, which was 81.3 (SD=4.9).

Discussion

The main finding from this study was that a large proportion of cognitively impaired subjects will progress to dementia in 3 years, although a substantial proportion will improve over the same time period without a higher risk of later progressing to dementia. Although the risks for the different outcomes (death, dementia, improvement) in the three severity levels of CIND varied, the pattern of evolution remained similar. Absence of a subjective memory complaint emerged as the only reliable predictor of improvement in CIND subjects. The comparison of our results with those from previous reports can be summarized in the following key points.

First, the progression to dementia appeared to be time dependent, occurring primarily within 3 years. The relative risks of progressing to dementia were substantially lower at the 6-year follow-up. A similar pattern was observed by Johansson and Zarit (12), who reported that rates of progression from mild cognitive disorder to dementia were higher over 2 years than over 7 years. Second, the proportions of subjects who improved were similar for the three severity levels. The improvement observed after 3 years in approximately one-quarter of the subjects with CIND is similar to the 22% reported by Helkala et al. (17) and slightly higher than the 15% found by Daly et al. (18). Third, the improvers in our study returned to a cognitively unimpaired state after 3 years without a significantly higher risk of later dementia than that of unimpaired subjects. To our knowledge, the present study is the first one that has followed CIND improvers during the 3 years after improvement and assessed the potential future excess risk of progressing to dementia.

The clinical relevance of this finding is indicated by three facts. First, the proportions of subjects who improved after 3 years were similar for the three CIND severity levels. Thus, even among subjects who were severely impaired, a quarter still improved after 3 years. Second, the majority of CIND improvers performed substantially better at follow-up, as many of them had a 3-point increase in score on the MMSE. Finally, this finding may not reflect learning effects, as similar rates of progression to dementia were found when incident cases of CIND were examined. At first follow-up, the subjects were acquainted with the MMSE, yet between the first and second follow-ups there was still an improvement in 19% of the individuals, compared to improvement in 25% of the subjects between baseline and first follow-up. This slight discrepancy can be explained by a higher mortality rate in the older population at second follow-up.

In addition, the absence of a subjective memory complaint at baseline was predictive of improvement 3 years later for subjects with mild CIND. Hogan and Ebly (14) found that informant-based report of memory loss predicted progression to dementia in subjects with CIND. Schofield et al. (7) reported that memory complaints were associated with cognitive decline but only in cognitively impaired individuals. These findings support the use of subjective memory complaints in the definition of “mild cognitive impairment” (4). Unexpectedly, no other factors were found to be associated with improvement in the present study. However, because of insufficient numbers of subjects with baseline disease, it was not possible to accurately assess somatic health as a potential predictor of improvement.

Finally, subjects with severe CIND had a higher relative risk of progressing to dementia, but a lower excess risk of death, than subjects with mild CIND. The latter finding may reflect the fact that there were higher percentages of baseline physical illnesses, such as coronary artery disease, malignancy, and cerebrovascular disease, in the subjects with mild CIND than in those with severe CIND. Thus, it is likely that the subjects with both mild CIND and other severe diseases were in a stage of terminal decline (27).

One limitation in the present study relates to the use of the MMSE to define CIND. The MMSE is regarded as a crude cognitive measure, but more sophisticated tools with higher sensitivity, and possibly lower specificity, would identify a higher number of false positives, thus reducing the power to predict progression to dementia. As the MMSE is a quick and simple tool, the proposed definition of CIND can be used in medical care at the primary level to identify high-risk individuals to be assessed further in a specialized clinical setting.

Another possible concern is that the definition of CIND was based on age-adjusted norms. The age stratification resulted in an even distribution of CIND subjects among the seven age groups. This method was specifically chosen because age and education affect MMSE performance (22). Thus, it would be inaccurate to define CIND according to a cutoff based on a global performance mean.

In addition, one could question the splitting of the CIND category into three severity levels, especially when the cutoff points were so close. In some age groups mild and severe CIND were differentiated by only one point on the MMSE. However, the results clearly support the current grading of impairment severity. Despite the closeness of the chosen cutoff points, the relative risks of progressing to dementia rose as a function of the severity of CIND.

Finally, the CIND definition in this study does not take into account the individual’s previous level of cognitive functioning. Some individuals may have had a low level of cognitive functioning throughout life, always functioning more than one standard deviation below the age- and education-based norms.

In conclusion, the present results show that although subjects with CIND have a higher risk of progressing to dementia, a large proportion of individuals in this category have lasting improvement, and the presence of a subjective memory complaint at baseline can help to differentiate between those individuals. Thus, although high rates of progression to dementia were observed, CIND appears to be a rather heterogeneous category. Further population-based studies are required to reliably identify the subgroup of individuals with CIND who are most likely to progress to dementia, so that pharmacological interventions can be applied as quickly and effectively as possible.

|

|

|

|

Received Jan. 16, 2001; revisions received June 18 and Aug. 27, 2001; accepted Sept. 20, 2001. From the Stockholm Gerontology Research Center and Division of Geriatric Epidemiology, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Occupational Therapy, and Elderly Care Research, Karolinska Institute; and the Department of Psychology, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden. Address reprint requests to Ms. Palmer, Stockholm Gerontology Research Center, Box 6401, S-11382 Stockholm, Sweden; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grants from the Foundation for Alzheimer and Dementia Research (SADF), the Gun and Bertil Stohnes Foundation, and the Swedish Research Council of Working Life and Social Sciences. The authors thank all participants of the Kungsholmen Project for data collection and management.

1. Ebly EM, Hogan DB, Parhad IM: Cognitive impairment in the non-demented elderly: results from the Canadian Study on Health and Aging. Arch Neurol 1995; 52:612-619Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Ritchie K, Touchon J: Mild cognitive impairment: conceptual basis and current nosological status. Lancet 2000; 355:225-228Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Cullum C, Huppert FA, McGee M, Dening T, Ahmed A, Paykel ES, Brayne C: Decline across different domains of cognitive functioning in normal ageing: results of a longitudinal population-based study using CAMCOG. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000; 15:853-862Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E: Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol 1999; 56:303-308Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Hanninen T, Hallikainen M, Koivisto K, Helkala E-L, Reinikainen KJ, Soininen H, Mykkanen L, Laakso M, Pyorala K, Riekkinen PJ: A follow-up study of age-associated memory impairment: neuropsychological predictors of dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995; 43:1007-1015Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Christensen H, Henderson AS, Korten AE, Jorm AF, Jacomb PA, Mackinnon AJ: ICD-10 mild cognitive disorder: its outcome three years later. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997; 12:581-586Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Schofield PW, Marder K, Dooneief G, Jacobs DM, Sano M, Stern Y: Association of subjective memory complaints with subsequent cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly individuals with baseline cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:609-615Link, Google Scholar

8. Bowen J, Teri L, Kukull W, McCormick W, McCurry SM, Larson EB: Progression to dementia in patients with isolated memory loss. Lancet 1997; 349:763-765Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Petersen RC, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Schaid DJ, Thibodeau SN, Kokmen E, Waring SC, Kurland LT: Apolipoprotein E status as a predictor of the development of Alzheimer’s disease in memory-impaired individuals. JAMA 1995; 273:1274-1278Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Howieson DB, Dame A, Camicioli R, Sexton G, Payami H, Kaye JA: Cognitive markers preceding Alzheimer’s dementia in the healthy oldest old. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997; 45:584-589Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Graham JE, Rockwood K, Beattie BL, Eastwood R, Gauthier S, Tuokko H, McDowell I: Prevalence and severity of cognitive impairment with and without dementia in an elderly population. Lancet 1997; 349:1793-1796Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Johansson B, Zarit SH: Early cognitive markers of the incidence of dementia and mortality: a longitudinal study of the oldest old. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997; 12:53-59Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Ritchie K, Ledesert B, Touchon J: Subclinical cognitive impairment: epidemiology and clinical characteristics. Compr Psychiatry 2000; 41:61-65Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Hogan DB, Ebly EM: Predicting who will develop dementia in a cohort of Canadian seniors. Can J Neurol Sci 2000; 27:18-24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Rogers SL, Farlow MR, Doody RS, Mohs R, Friedhoff LT (Donepezil Study Group): A 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1998; 50:136-145Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Rosler M, Anand R, Cicin-Sain A, Gauthier S, Agid Y, Dal-Bianco P, Stahelin HB, Hartman R, Gharabawi M: Efficacy and safety of rivastigmine in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: international randomised controlled trial. Br Med J 1999; 318:633-640Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Helkala EL, Koivisto K, Hanninen T, Vanhanen M, Kuusisto J, Mykkanen L, Laakso M, Riekkinen P: Stability of age-associated memory impairment during a longitudinal population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997; 45:120-122Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Daly E, Zaitchik D, Copeland M, Schmahmann J, Gunther J, Albert M: Predicting conversion to Alzheimer disease using standardized clinical information. Arch Neurol 2000; 57:675-680Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Fratiglioni L, Grut M, Forsell Y, Viitanen M, Grafstrom M, Holmen K, Ericsson K, Backman L, Ahlbom A, Winblad B: Prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in an elderly urban population: relationship with age, sex, and education. Neurology 1991; 41:1886-1892Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Fratiglioni L, Grut M, Forsell Y, Viitanen M, Winblad B: Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in a population survey: agreement and causes of disagreement in applying Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised Third Edition, criteria. Arch Neurol 1992; 49:927-932Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189-198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Frisoni GB, Fratiglioni L, Fastbom J, Viitanen M, Winblad B: Mortality in non-demented subjects with cognitive impairment: the influence of health-related factors. Am J Epidemiol 1999; 150:1031-1044Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Agüero-Torres H, Fratiglioni L, Guo ZC, Viitanen M, Von Strauss E, Winblad B: Dementia is the major cause of functional dependence in the elderly: 3-year follow-up data from a population-based study. Am J Public Health 1998; 88:1452-1456Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Fastbom J, Claesson CB, Cornelius C, Thorslund M, Winblad B: The use of medicines with anticholinergic effects in older people: a population study in an urban area of Sweden. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995; 43:1135-1140Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Norusis MJ: SPSS for Windows: Base System User’s Guide and Advanced Statistics, Release 6.1. Chicago, SPSS, 1994Google Scholar

26. Wald A: Tests of statistical hypotheses concerning several parameters when the number of observations is large. Transactions of the Am Mathematical Soc 1943; 54:426-482Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Small BJ, Backman L: Time to death and cognitive performance. Current Directions in Psychol Sci 1999; 8:161-172Crossref, Google Scholar