Suicide Among New York City Police Officers, 1977–1996

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors assessed the suicide rates of New York City police officers during a recent period. METHOD: The authors reviewed death certificates of active New York City police officers who died from 1977 through 1996 (N=668); age-, gender-, and race-specific suicide rates among New York City police officers and the city’s residents were determined. RESULTS: The police suicide rate was 14.9 per 100,000 person-years, compared with a demographically adjusted suicide rate of New York City residents of 18.3 per 100,000 person-years. Suicide rates among male police officers were comparable to their reference population. Female police officers had a higher risk of suicide than female residents of New York, but the number of suicides of female police officers was small. CONCLUSIONS: The rate of suicide among New York City police officers is equal to, or even lower than, the suicide rate of the city’s resident population.

For the 738,000 law enforcement officers in the United States, suicide has been considered an occupational hazard, resulting from job stress, high rates of alcoholism and marital discord, and the availability of firearms (1–5). Although police officers are thought to have a very high suicide rate, few studies have systematically assessed this rate. Therefore, we sought to determine if the suicide rate of New York City police officers exceeded that of the general population or showed changes over a recent period.

Method

The New York City Police Department provided the names, dates, and locations of death for all officers who died during the study period, 1977–1996, along with the annual numbers of active police officers stratified by age category, gender, and race. Death certificates from the certifying jurisdiction were reviewed. Only deaths certified as suicide (ICD codes 950–959) were used to calculate suicide rates. The New York City Health Department provided the annual numbers of city residents who committed suicide, stratified demographically. The annual suicide rate for police officers was calculated as the number of police suicides per year, divided by the number of officers on the force as of July 1 each year, expressed per 100,000 person-years. Annual crude rates of suicide were calculated as the annual number of city residents who committed suicide, divided by the city’s resident population (provided by the 1980 and 1990 U.S. census), expressed per 100,000 person-years. The suicide rate among city residents was adjusted to the demographic characteristics of the city’s police force. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the rates.

To account for misclassification bias (6) we calculated an additional mortality rate comprising all police officer deaths that involved methods typically used in suicides—specifically, carbon monoxide poisoning, hanging, falling from a height, or use of firearms—but that had been certified as accidental or undetermined in manner. This rate used the sum of these deaths per year as the numerator and the same police force denominator used in calculating the suicide rate for police officers. We added this rate to the suicide rate to yield an upper range for the estimate of police suicides.

Results

Among the 668 deaths of police officers from 1977 to 1996, 80 were certified suicides (mean age=33.5 years, SD=9.7, range=21–59). Firearms were used in 75 of these (93.8%); other methods included hanging (N=3), carbon monoxide poisoning (N=1), and falling from a height (N=1).

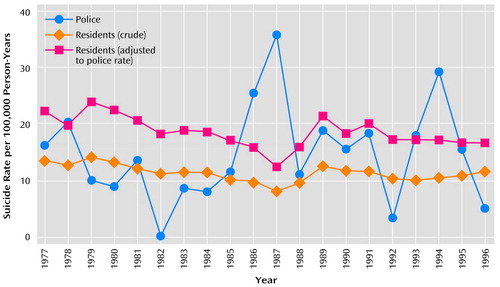

The overall suicide rate among police officers during the period was 14.9 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI=11.9–18.6), compared with the demographically adjusted suicide rate for the New York City population (18.3 per 100,000 person-years, 95% CI=18.0–18.6). The suicide rate for the upper end of the range, which included the 80 police officer suicides plus 22 additional deaths by methods usually seen in suicides, was 19.0 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI=15.5–23.1). The annual number of suicides ranged from 0 in 1982 to 10 in 1987 (mean=4.0, SD=2.6). Although the annual rates varied (Figure 1), there were no trends. For 17 of the 20 years examined, the police officer suicide rate remained below that of the demographically adjusted rate of the city’s population.

The 62 suicides among white male police officers yielded a rate of 16.8 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI=13.9–23.2), which was lower than that of white men of comparable age in the New York City population (21.4 per 100,000 person-years, 95% CI=20.8–22.0). The 11 suicides among nonwhite male police officers yielded a suicide rate of 12.0 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI=7.7–27.1), which was approximately the same as that of the reference group in the population (12.4 per 100,000 person-years, 95% CI=11.9–13.0). In contrast, there were seven suicides among female police officers. Female police officers were about four times as likely to die by suicide as women of comparable age in the general population (13.1 versus 3.4 per 100,000 person-years, 95% CI=5.7–28.2 and 3.2–3.7, respectively).

Discussion

We found that the suicide rate among New York City police officers was no higher than the adjusted suicide rate of the city’s population and the rates had not risen recently. Even the upper range of the estimate—which likely includes some police suicides that had been misclassified as accidents—did not exceed the demographically adjusted suicide rate of the general population. The notion that police are at a substantially higher risk of suicide than the average individual may, in part, result from the publicity surrounding a police suicide. However, with one exception (7), studies have shown police suicide rates to be lower than those of the general population (8–11). Our study, however, should not be interpreted to mean that suicide is not a problem among police officers. Since recruits undergo psychological screening, it could be argued that a police suicide rate that is not substantially lower than that of the general population is effectively high (12, 13).

Police suicides likely have multiple determinants. Job stresses often include an officer’s exposure to trauma and death, including suicide; difficult administrative policies, changing assignments, and irregular work hours; poor equipment; public mistrust; governmental criticism of police actions; and judicial decisions that undermine police work (1, 7). Almost all police suicides result from firearms; the easy access and socialization of officers to handguns undoubtedly contribute to the suicide rate (14, 15).

Marital problems, alcoholism, and job suspensions are the most important individual characteristics associated with police suicides (16). Age, race, years of service, and rank were not associated with this risk. Although the suicide rate among female police officers exceeds that of women in the general population, both the number of suicides of female police officers and the number of women in the New York City Police Department are low. Nevertheless, a gender-associated risk bears further investigation.

Police departments, with their tight organizational structures, offer both opportunities and challenges for suicide-prevention programs. The New York City Police Department and its police union have sponsored counseling programs for officers (17). However, barriers for officers seeking psychiatric care remain formidable, since officers worry that psychiatric evaluation can result in job sanctions, reassignment, restriction of firearm privileges, missed promotions, and stigmatization. Although it is difficult to assess the efficacy of intervention programs, we believe that these programs may be effective if started early during officer training and delivered regularly throughout an officer’s career to keep the rate of suicide among police as low as possible.

Received Nov. 21, 2001; revision received July 16, 2002; accepted July 23, 2002. From the Department of Psychiatry, Weill Medical College of Cornell University. Address reprint requests to Dr. Marzuk, Office of Curriculum and Educational Development, Joan and Sanford I. Weill Medical College of Cornell University, 1300 York Ave., New York, NY 10021; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a grant from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and the Reader’s Digest Foundation/New York Community Trust.

Figure 1. Annual Suicide Rates in 1977–1996 for New York City Police Officers and Residents

1. McCafferty FL, McCafferty E, McCafferty MA: Stress and suicide in police officers: paradigm of occupational stress. South Med J 1992; 85:233-243Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Danto BL: Police suicide. Police Stress 1978; 1:32-40Google Scholar

3. Violante JM: Trends in police suicide. Psychol Rep 1995; 77:688-690Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Territo L, Vetter HJ: Stress and police personnel. J Police Sci and Administration 1981; 9:195-208Google Scholar

5. Friedman P: Suicide among police: a study of ninety-three suicides among New York City policemen 1934-1940, in Essays in Self-Destruction. Edited by Shneidman E. New York, Science House, 1968, pp 414-449Google Scholar

6. Violante JM, Vena JE, Marshall JR, Petralia S: A comparative evaluation of police suicide rate validity. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1996; 26:79-85Medline, Google Scholar

7. Nelson Z, Smith W: The law enforcement profession: an incident of high suicide. Omega (Westport) 1970; 1:293-299Google Scholar

8. Heiman MF: Police suicides revisited. Suicide 1975; 5:5-20Medline, Google Scholar

9. Dash J, Reiser M: Suicide among police in urban law enforcement agencies. J Police Sci and Administration 1978; 6:18-21Google Scholar

10. Josephson RL, Reiser M: Officer suicide in the Los Angeles Police Department: a twelve-year follow-up. J Police Sci and Administration 1990; 17:227-229Google Scholar

11. Loo R: Suicide among police in a federal force. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1986; 16:379-388Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Hill KQ, Clawson M: The health hazards of “street level” bureaucracy: mortality among the police. J Police Sci and Administration 1988; 16:243-248Google Scholar

13. Violante JM, Vena JE, Marshall JR: Disease risk and mortality among police officers: new evidence and contributing factors. J Police Sci and Administration 1986; 14:17-23Google Scholar

14. Heiman MF: Suicide among police. Am J Psychiatry 1977; 134:1286-1290Link, Google Scholar

15. Heiman MF: The police suicide. J Police Sci and Administration 1975; 3:267-273Google Scholar

16. Janik J, Kravitz HM: Linking work and domestic problems with police suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1994; 24:267-274Medline, Google Scholar

17. Ivanoff A: The New York City Police Suicide Project: Evaluation of Film and Training. New York, Police Foundation, 1974Google Scholar