Interventions to Improve Medication Adherence in Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Although nonadherence with the antipsychotic medication regimen is a common barrier to the effective treatment for schizophrenia, knowledge is limited about how to improve medication adherence. This systematic literature review examined psychosocial interventions for improving medication adherence, focusing on promising initiatives, reasonable standards for conducting research in this area, and implications for clinical practice. METHOD: Studies were identified by computerized searches of MEDLINE and PsychLIT for the years between 1980 and 2000 and by manual searches of relevant bibliographies and conference proceedings. Key articles were summarized. RESULTS: Thirteen (33%) of 39 identified studies reported significant intervention effects. Although interventions and family therapy programs relying on psychoeducation were common in clinical practice, they were typically ineffective. Concrete problem solving or motivational techniques were common features of successful programs. Interventions targeted specifically to problems of nonadherence were more likely to be effective (55%) than were more broadly based treatment interventions (26%). One-half (four of eight) of the successful interventions not specifically focused on nonadherence involved an array of supportive and rehabilitative community-based services. CONCLUSIONS: Psychoeducational interventions without accompanying behavioral components and supportive services are not likely to be effective in improving medication adherence in schizophrenia. Models of community care such as assertive community treatment and interventions based on principles of motivational interviewing are promising. Providing patients with concrete instructions and problem-solving strategies, such as reminders, self-monitoring tools, cues, and reinforcements, is useful. Problems in adherence are recurring, and booster sessions are needed to reinforce and consolidate gains.

There is overwhelming evidence that antipsychotics can be effective in treating the symptoms of schizophrenia (1). However, the failure of many patients with schizophrenia to follow their prescribed medication regimen has significantly undermined the promise of antipsychotic medications. Rates of medication nonadherence among outpatients with schizophrenia have been found to approach 50% during the first year after hospital discharge (2, 3). The actual rate of nonadherence may be even higher, as the estimates do not account for individuals who refuse treatment or drop out of follow-up studies. Moreover, there is little evidence that progress has been made in increasing adherence, despite the advent of newer antipsychotic medications with less severe and disabling side effects (4).

Poor adherence with antipsychotic medications increases the risk of relapse. Nonadherent patients have an average risk of relapse that is 3.7 times greater than that of adherent patients (5). Relapse due to nonadherence may also be more severe and dangerous. One of the more disturbing consequences of medication nonadherence is an increased potential for assault and dangerous behaviors, especially during periods of psychosis (5).

A coherent approach for reducing nonadherence would benefit substantially from a theoretical model that organizes existing research findings and provides guidance to points of leverage for improving adherence. The traditional models dominant in the study of patient adherence, such as the Health Belief Model, are typically based on a rough cost-benefit calculus in which the patient considers the advantages and burdens of taking medications by weighing the probabilities of risks and benefits (6). While these models have been useful as organizing frames, they have had limited predictive value.

It has long been recognized that external influences independent of patient decision making also affect adherence. The Health Belief Model attempts to take such factors into account by considering cues to action represented, for example, by publicity affecting the illness revelations of public personalities such as Betty Ford and Magic Johnson. Other models focus specifically on the treatment and communication process and the extent to which patients understand and implement the treatment regimen (7). Still other models focus on parallel processing on the cognitive level through disease and treatment schemas and on the motivational level through emotional response (8). These models illustrate the importance of specific coping plans to implement intent.

It is clear that the highly rational assumptions of models such as the Health Belief Model are not helpful in understanding and predicting adherence in schizophrenia. Although not fully formulated, patient schemas and coping plans may offer more potential for improving adherence in schizophrenia. It is essential to go beyond the usual individual psychological focus of these models and give attention to contextual cues and reinforcements that are more amenable to intervention within treatment programs. The existing research literature is usually problem driven and atheoretical and is of limited use for explicating these theoretical ideas. In our review, however, we focus not only on the individual variables but wherever possible consider the contextual factors that may impede or encourage a higher rate of adherence.

Previous reviews have summarized and critiqued intervention efforts in the medical field, although we could find no published reviews that focused specifically on schizophrenia (9, 10). This review 1) provides a comprehensive summary of interventions that have sought to improve adherence to antipsychotic medications in patients with schizophrenia, 2) assesses the quality and effectiveness of these interventions, and 3) evaluates the state of knowledge and suggests avenues for future research.

Method

Study Selection Criteria

The review consisted of studies examining interventions to modify medication adherence in individuals with schizophrenia. It encompassed English-language published and unpublished studies and doctoral dissertations completed between 1980 and 2000.

In our initial selection criteria, studies chosen for this review included those with 1) a random-assignment design comparing two or more groups, at least one of which received psychosocial treatment; 2) study group size of at least 10 subjects; 3) participants with a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder; and 4) a measure of antipsychotic medication adherence either as a primary or secondary outcome variable.

While conducting the literature review we discovered several interesting and innovative studies that did not meet all of the aforementioned criteria. To avoid excluding these works, we broadened our criteria. Studies were included if 1) a majority of the participants had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and 2) there was a comparison of outcome between two or more groups, not necessarily with a random-assignment design.

Search Strategy

PsychLIT and MEDLINE covering the years 1980 through 2000 were searched for relevant studies. Dissertations were searched by means of Dissertation Abstracts International. Key search words included: adherence; compliance or noncompliance; schizophrenia, schizoaffective, or schizophreniform; neuroleptics, antipsychotics, or medication; random assignment, controlled, or double blind; and intervention or outcome. Bibliographies from primary sources, reviews, and recent issues of established psychiatric journals, including the American Journal of Psychiatry,Archives of General Psychiatry,Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica,British Journal of Psychiatry, and Schizophrenia Bulletin published between January 1995 and December 2000, were manually scanned for evidence of trials overlooked by the computerized search. Proceedings from recent professional meetings were examined for posters and presentations examining adherence. Authors of the studies included in the review were contacted for information about unpublished data or additional studies.

Some studies conceptualized adherence as a mediating variable that might influence the relationship between the interventions and outcomes. These articles may not mention “adherence” or the other key words in the abstract. To maximize identification of these reports, we carefully reviewed all random-assignment studies with a psychosocial intervention for any reference to adherence. The authors of a meta-analysis on psychosocial treatments in schizophrenia provided a list of published studies that included adherence as an outcome (11).

Identification of Studies and Data Extraction

Three of the authors reviewed all extracted articles to ensure that they met inclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved in regular team meetings. A total of 362 articles were obtained, of which 288 did not address medication adherence. An additional 29 studies explored medication adherence as an outcome but were excluded for the following reasons: six did not specify a diagnosis or had few patients with schizophrenia; nine did not include a comparison group or did not compare results between intervention groups and comparison groups; eight described the measurement of medication adherence but did not report related results; and six measured behaviors conceptually related to adherence, such as medication knowledge, but not actual drug intake. We identified three unpublished studies where procedures were ongoing, but data were not available. A total of 45 articles that represented 39 studies were included in this review.

From the selected articles, we abstracted information about the type and duration of the intervention, the size and diagnostic composition of the study groups, method of measuring medication adherence, and adherence outcomes. Differences between intervention groups and comparison groups or among intervention groups are indicated if they reached statistical significance (p<0.05).

Results

General Findings

Thirty-nine studies were reviewed. Twenty-three studies met our original inclusion criteria, and 16 were identified during the second screening phase. In the latter group were 15 studies that included cohorts with mixed diagnoses and six studies that used quasi-experimental, nonrandom assignment.

Of the 23 studies that met our original inclusion criteria, six (26%) demonstrated significant effects for treatment adherence. Seven (44%) of the additional 16 studies also demonstrated significant effects.

A majority of the studies that reported significant effects found improved clinical outcomes in the intervention group at follow-up (69%; N=9). This clinical advantage was manifest in fewer psychiatric symptoms (12–17), fewer hospitalizations (18), fewer days in the hospital (18, 19), and prolonged or extended community tenure (20, 21).

Treatment Modalities

The studies were classified into five broad categories by treatment modality: individual, family, group, community, and mixed. Mixed-modality studies include those comparing one treatment modality with another (e.g., group versus family therapy) and those in which various modalities were integrated into one treatment program (e.g., individual sessions and family therapy).

Among the random-assignment studies (N=33), significant effects were found in two of four studies of individual interventions, three of 12 studies of family interventions, none of two studies of group interventions, three of six studies of community interventions, and three of nine studies with mixed treatment modalities. One of four community interventions and one of two group interventions with other than random assignment reported significant effects.

Therapeutic Orientation

While many of the interventions were multifaceted, some general classifications on the basis of therapeutic philosophy or orientation were possible. Psychoeducational interventions focused primarily on dissemination of knowledge about schizophrenia, treatment, and medications, without focusing on attitudinal and behavioral change to achieve medication adherence. Group therapy was based on the importance of peer support and shared identification. Family interventions derived from a belief in the family as a critical influence on the course of a patient’s illness.

Cognitive treatments targeted patients’ attitudes and beliefs toward medication. These interventions centered on the assumption that adherence is a coping behavior that is heavily determined by the personal construction of the meaning of medication and illness. Behavioral modification techniques assumed that behaviors are acquired through learning and conditioning and can be modified through rewards and punishment, reinforcement, provision of cues, and the promotion of self-management (22). In such interventions, a detailed behavioral analysis of the problem was often conducted, and treatment procedures were targeted at specific components of the behavior. Community programs typically involved a complex variety of supportive and rehabilitative services delivered to clients in the community rather than in a clinic.

Specificity and Intensity of Interventions

Medication adherence was a central goal in all four studies of individual interventions (20, 21, 23, 24), three studies of mixed interventions (22, 25–27), and two studies of group interventions (28, 29). The community studies emphasized extending client tenure in the community and improving daily function, and most of the group studies emphasized psychoeducational goals.

Interventions that made medication adherence the primary goal were more successful in increasing medication use than those that viewed adherence as a secondary outcome. Five (56%) of nine studies that focused on adherence found significant results. By contrast, only 27% of the studies that did not specifically concentrate on adherence found a significant change in medication adherence.

There was little relationship between the intensity of the interventions, as measured by duration or number of sessions, and effectiveness. Some interventions that included a relatively large number of sessions (e.g., 20 sessions [30]) or were extended in duration (e.g., 36 months [31]) were no more effective than usual care in reducing medication nonadherence. By contrast, some interventions that included relatively few sessions (e.g., four to six sessions [20, 21]) or were brief (e.g., 2 months [16]) were highly effective.

There was an interaction between specificity and duration. Three of the four short intervention studies that reported significant findings also had medication adherence as a central goal of the study (20, 22, 23), while many of the studies of longer-duration interventions did not.

Description of Interventions

Individual interventions

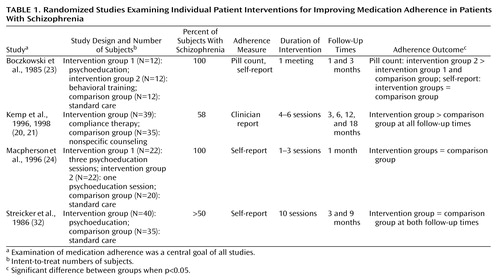

Four individual intervention studies that met our inclusion criteria were found (20, 21, 23, 24, 32) (Table 1). (The two references by Kemp et al. [20, 21] describe the same study.) Of the two studies that reported significant findings, one examined motivational interviewing, and the other compared behavioral treatment to a psychoeducational intervention and nonspecific counseling. The studies reporting positive results both examined psychoeducational interventions.

Kemp and colleagues (20, 21) tested compliance therapy, a combination of cognitive approaches and motivational interviewing to enhance medication adherence. Intervention sessions encouraged patients to articulate their beliefs and ambivalence about antipsychotic medications while focusing on adaptive behaviors and the importance of staying well. Therapists helped patients connect indirect benefits of medication, such as improved personal relations, to adherence and symptom reduction. Inpatients who received compliance therapy demonstrated sustained gains in medication adherence over 18 months after hospital discharge and better measures of insight and attitudes toward treatment (20).

The study by Boczkowski and colleagues (23) compared the efficacy of behavioral training versus psychoeducation or standard treatment. Participants who received behavioral training were more adherent at the 3-month follow-up than participants who received psychoeducation or standard treatment. The authors concluded that behavioral interventions were more effective because they acted directly on pill-taking behaviors through stimulus cues and feedback.

Group interventions

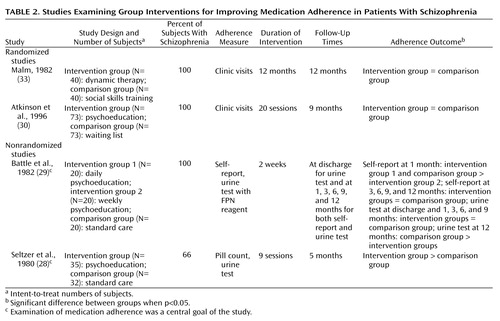

Of the four group interventions that met our inclusion criteria (28–30, 33), one program, which was primarily psychoeducational but also involved a behavioral component, was successful (Table 2). In the study by Seltzer and co-workers (28), patients in three intervention groups received nine lectures about their disorder and its pharmacological management along with reinforcement for desirable medication-taking routines. Group resources were used to help patients deal with fears and resistance that interfere with adherence. Patients who received the intervention were more adherent than the comparison patients at 5-month follow-up. Substantial loss of intervention group (28%) and comparison group (74%) patients raises concerns of attrition bias.

Family interventions

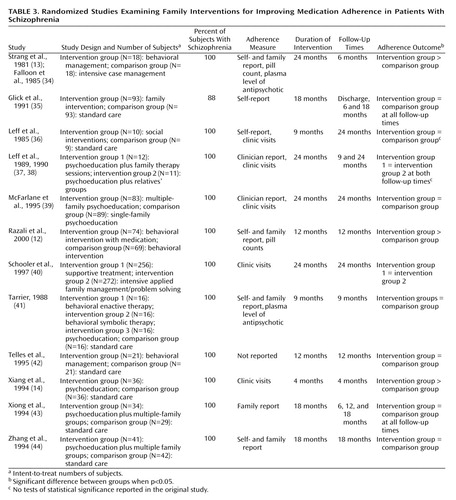

A variety of psychoeducational, behavioral, and problem-solving strategies have been employed to optimize families’ coping and promote better outcomes for patients. Some interventions involve patients’ participation, while others work exclusively with family members. Of the 12 family studies that were reviewed (12–14, 34–44), only three reported significant differences in adherence (Table 3). (The references by Strang et al. [13] and Falloon et al. [34] describe the same study. Two references by Leff et al. [37, 38] describe the same study.) Two of the three successful family interventions included a behavioral component.

Falloon et al. (34) compared experimental behavioral family therapy to individual supportive psychotherapy. The experimental treatment was home-based and focused on enhancing family functioning, while the individual sessions were conducted in the clinic and organized around the needs of the individual patients. After 6 months the family therapy group showed significantly less transition to depot medication and better adherence with oral medication. Most patients in individual therapy took less than one-half of their prescribed medications, while only about one-fifth of the patients in the family-based intervention were nonadherent (13).

Xiang and colleagues (14) investigated family therapy in a rural province of China. Families in the comparison group were given only a prescription, while families in the intervention group were provided basic information about mental diseases, training in problem-solving skills, and strategies for medication adherence. After 4 months, almost one-half of the patients in the intervention group were taking medication as prescribed, compared to only about 15% of the comparison subjects. Significantly more families in the intervention group recognized mental disorder as an illness and were willing to cooperate with treatment.

Razali and colleagues (12) studied the effectiveness of behavioral family therapy modified to emphasize close monitoring of adherence, reinforcement of the care provider’s role in supervising medication, practical information about taking medications, and respect for prevailing cultural beliefs concerning mental illness. At follow-up, the intervention group demonstrated significantly greater medication adherence, measured by pill counts and interviews with care providers, than the comparison group.

Community-based interventions

Different models of community-based care have been developed to meet the diverse needs of persons with severe mental illnesses and to optimize their social adjustment. Key components of community-based interventions include the provision of a strong and supportive social network; close monitoring of clinical status, including the medication regimen; and provision of stable housing and other supportive services (45). Only a small proportion of studies of community care, notably those involving assertive community treatment and intensive case management models, have included assessments of medication adherence, perhaps because of the peripheral role of psychiatrists in these programs (46).

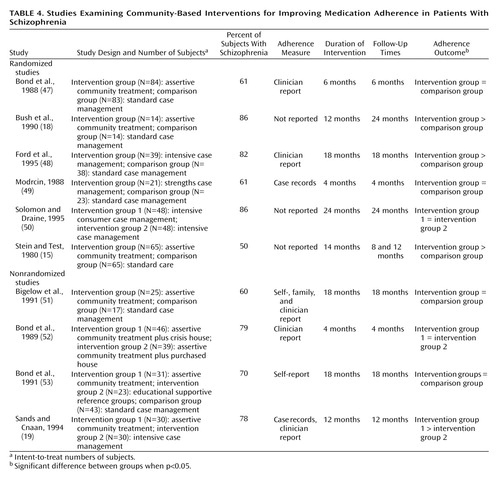

Most studies of assertive community treatment or intensive case management involved comparisons with less intensive or standard models of care. Of the 10 community studies that met our selection criteria (15, 18, 19, 47–53), four reported that the intervention was associated with significantly greater medication adherence than was a comparison condition (Table 4). None of the studies included a rigorous assessment of medication adherence. Two of the four studies demonstrating an effect (15, 18) provided no information on their method for measuring adherence. Sands and Cnaan (19) used medical records and interviews with case managers to assess medication adherence. Ford and colleagues (48) measured medication adherence at baseline and 18 months with two Likert-type response items completed by case managers.

Despite the uneven quality of research on the effects of community care programs on medication adherence, many programs closely monitored patients with a history of nonadherence and considered regular medication use an important treatment goal (54). The reduction in hospitalization widely associated with community models of care may be a consequence of improved medication adherence.

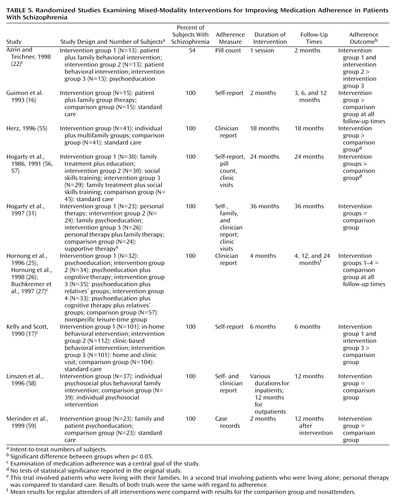

Mixed-modality interventions

Mixed-modality studies tested the efficacy of one treatment modality versus another (e.g., group versus family therapy) and/or included interventions with various modalities integrated into one treatment program (e.g., individual sessions and family therapy). Of the nine studies of mixed modalities that met our inclusion criteria (16, 17, 22, 25–27, 31, 55–59), five showed positive effects, but only three of these studies reported significance tests (Table 5). (Two references by Hogarty et al. [56, 57] describe the same study. Two references by Hornung et al. [25, 26] and a reference by Buchkremer et al. [27] describe the same study.)

Azrin and Teichner (22) evaluated the effectiveness of a behavioral intervention for patients versus a combined patient and family intervention. The two intervention groups were taught detailed behavioral guidelines for each step of the medication-taking sequence. In the combined approach, family members collaborated with patients in implementing behavioral strategies. The comparison group received an information packet describing psychotropic medications. The intervention groups showed significantly greater adherence than the comparison group, although no differences were found between the two intervention conditions and no improvements were found in clinical symptoms.

Kelly and Scott (17) tested a combined family and individual intervention that emphasized individualized concrete behavioral “compliance plans,” with less emphasis given to attitudes and beliefs. In the first condition, the study staff collaborated with patients and their families in devising an individualized behavioral plan for improving adherence. These plans ranged in complexity from simple positive reinforcement to increased family involvement in outpatient programs. In the second intervention, study staff helped patients identify concerns, formulate goals, and evaluate the success of treatment during meetings with their doctors. The third intervention group received both interventions, and the comparison group received standard care alone. Six months after completion of the intervention, the intervention groups were found to have superior adherence and lower symptom and hospital readmission rates. Those who received both interventions had the best outcomes.

Guimon and colleagues (16) studied a patient and family approach that involved group discussion of medication attitudes and behaviors. During group sessions, patients discussed their conflicts about taking medication, while therapists and other group members provided suggestions addressing these conflicts. Family members participated in similar groups. Compared with a group receiving a time-equivalent standard care, the intervention group exhibited superior medication adherence, less severe symptoms, and more favorable attitudes toward their medications after 12 months.

Cultural Context

Although most studies were conducted at urban mental health centers in the United States, some variation in cultural context existed. Three studies were conducted in China during the early 1990s (14, 43, 44). One of these studies reported significant effects of family psychoeducation on medication adherence. During this period, only minimal community-based mental health facilities were available in China. Earlier research suggested that among Chinese outpatients educational deficits about psychotropic medications are common and closely correlated with medication nonadherence (60). These factors might have increased the effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions, beyond what would be achieved in clinical settings in the United States.

In Malaysia, where mental illness is commonly believed to be caused by supernatural agents, counselors who were applying the intervention were specifically instructed not to challenge this belief while conveying a positive attitude toward antipsychotic medications and confidence in modern treatments (12, 61). Incorporating local concepts of illness may have helped to avoid conflict, strengthen the clinical relationship, and promote improved management.

Methods of Defining and Assessing Adherence

Substantial variability existed across studies in the definition and measurement of medication nonadherence. The most common definition involved a dichotomous (all or none) variable measured by the subjective reports of patients, family members, physicians, or case managers. Single ratings of adherence were sometimes used to cover periods spanning as long as 18 months (48). Comparatively few studies involved corroboration of global subjective reports with objective measures such as pill counts (12, 22, 23, 28, 34, 56, 57) or physiological data (13, 28, 29, 34). Few community studies described the methods used to monitor or evaluate medication nonadherence.

Summary of Intervention Results

No one specific modality demonstrated overwhelming success in improving adherence, although some modalities were represented by only a few studies. Psychoeducational interventions that did not focus on attitudinal and behavioral change were largely unsuccessful in improving adherence. With the exception of the study conducted in China (14), none of the studies in which psychoeducational interventions were administered to individuals or families found significantly altered medication adherence (24, 32, 37–39, 41, 44). One (28) of three (28–30) studies of psychoeducational interventions administered to patient groups reported improved medication adherence. None of the multimodal studies including a psychoeducational component reported significant results (25–27, 31, 59).

Family therapy alone did not have a large effect on adherence. Of the three family studies that reported positive effects, one took place in China and one in Malaysia. One study showed that a behavioral intervention was not made more effective by the addition of family therapy (22).

A number of studies that used behavioral interventions were successful in promoting adherence (12, 17, 22, 23). Two studies (22, 23) compared psychoeducational techniques with behavioral interventions and found the latter to be superior in promoting adherence.

Programs that used cognitive techniques and targeted patients’ attitudes toward medication were often effective in improving medication adherence (16, 20, 21). In these interventions, the patient’s desire to comply was not assumed, and a personal construction of meaning was emphasized. The work of Kemp and colleagues (20, 21) on “compliance therapy” has provided a promising illustration of this approach.

Finally, there was modest evidence that the assertive community treatment and intensive case management models of community care were effective in promoting medication adherence. Four of the 10 studies of these models included in this review reported positive results (15, 18, 19, 48).

Discussion

Important differences existed across the reviewed studies, and many of the interventions were complex and multifaceted, making it difficult to identify elements that contributed to the success or failure of interventions. The conclusions we derived are necessarily tentative.

Our review suggests that psychoeducation for patients with schizophrenia and their families is largely ineffective in improving adherence with antipsychotic medications. However, psychoeducation programs are quite variable in their emphasis on medication treatment, making general statements difficult. Psychoeducation interventions without medication adherence as a key treatment element were generally less likely to improve adherence.

We did not assess the effects of psychoeducation on other important outcomes such as patient and family knowledge about schizophrenia or its treatment. Several interventions that were effective in reducing nonadherence included psychoeducation but also incorporated behavioral aspects of medication taking or motivational approaches that link medication adherence to personal goals. For some patients, increasing knowledge about their illness and about medication and its side effects may actually be disturbing (62). In other contexts, interventions that impart information associated with a high level of fear have been shown to reduce adherence and activate defensive avoidance (63).

Behavioral interventions assume that adherence is modified by frequent repetition and behavioral modeling. Common behavioral strategies include providing patients with detailed instructions and concrete problem-solving strategies such as reminders, self-monitoring tools, cues, and reinforcements. In one intervention, patients were also taught how to negotiate treatment issues with mental health providers (17). Similar methods have been found to improve the management of diabetes and hypertension (64, 65) and to reduce high-risk HIV behaviors among adults with severe mental illness (66).

Family therapy programs were generally ineffective in improving adherence. Those programs that incorporated a behavioral component were somewhat more promising (12, 34).

Interventions developed to address medication nonadherence were more likely to succeed than programs covering a wider range of problem areas. Behavioral improvement in adherence may require a more intensive and concentrated approach than is commonly available in less specialized interventions. In this regard, assertive community treatment may be an important exception. Medication adherence is often a key clinical goal in assertive community treatment within a broad-based and vigorous program to deliver relevant psychiatric and rehabilitative services. Although the literature suggests that assertive community treatment promotes medication adherence (15, 18), little is known about how it achieves these effects.

Interventions specifically targeting medication nonadherence tended to select inpatients or other groups at high risk for stopping their medications (16, 20, 21). By contrast, several studies that were not specifically focused on medication nonadherence included patients at relatively low risk for nonadherence. High rates of medication adherence were common in the intervention and comparison groups of the family and group studies (33, 37–39), as programs typically require family members to be involved in the care of their ill relatives. This requirement may make it difficult to detect an increase in adherence. Families who are ambivalent about antipsychotic medications or who initially refuse to participate in treatment may offer a greater opportunity to observe intervention effects because patients from such families are at high risk for stopping their medications (67).

Patients with a strong history of nonadherence are underrepresented in outcome research. Because medication nonadherence is closely associated with treatment dropout, patients who are prone to nonadherence are difficult to recruit and retain in clinical care and research protocols. For this reason, inpatient units provide a reasonable setting to initiate efforts to promote adherence and study high-risk patients. Because inpatients typically assume greater control over taking their medications after hospital discharge, interventions should be adapted to the changing realities of medication management outside the highly controlled hospital setting.

In the months after hospital discharge, patients are particularly vulnerable to drug default, with half of first-episode patients with psychosis discontinuing treatment during the first 6 months (3). This may be a critical period for providing services to ensure continuity of pharmacological treatment. Clinical experience suggests that problems with medication adherence are recurring, making booster sessions necessary to reinforce and consolidate gains made during short-term, more intensive interventions. Although we found little relation between the duration of the interventions and their effectiveness, several interventions did not extend beyond a few months. Given the long course of recovery of symptom exacerbations in schizophrenia (68), we recommend that clinical interventions targeting nonadherence continue for at least 18 months with quarterly assessments to identify patient cycling and response to treatment and to assess medication-related behaviors.

There is no generally accepted definition of medication nonadherence in schizophrenia. Ideally, nonadherence should be defined in a manner that is empirically informed and clinically meaningful. We suggest defining nonadherence with oral antipsychotics as complete cessation of medication for at least 1 week (17, 67). A majority (91%) of patients with schizophrenia who stop taking medication for more than 1 week continue not to take medication until they relapse (69).

Clinicians often become aware of dosage deviations that fall short of persistent cessation. Although it is commonly assumed that patients who frequently miss doses are at risk for subsequent relapse, the clinical significance of dosage deviation remains unknown. A few studies in our review used continuous subjective measures of adherence with well-defined anchor points to capture dosage deviation. Novel techniques for measuring adherence are being tested. For example, Cramer and Rosenheck (70) used a microelectronic device (MEMS) (Aprex, Union City, Calif.) to monitor adherence to antipsychotic medication. The MEMS unit is attached to the medication bottle and records the date and time of each bottle opening, providing close monitoring of dosage deviations. Pharmaceutical companies have developed accurate and easy to administer urine tests (point-of-care assays) to assess antipsychotic levels. These tests are capable of detecting subtle changes in pill taking behavior or drug metabolism.

Despite these promising trends, most studies in our review relied on dichotomous subjective reports of pill taking to measure adherence, an approach that overestimates adherence (5) and reduces the likelihood of detecting intervention effects. A majority (62%) of the studies in our review that employed specific, objective measures of adherence such as pill counts and plasma levels found improved adherence in the intervention group, even when the intervention was not specifically targeted toward adherence. Objective measures may enhance the chance of detecting dosage deviations and subtle, but clinically relevant, differences in medication-taking behavior, but the greater accuracy of objective measures must be weighed against their higher cost and the risk of lowering study participation among patients of greatest clinical interest.

With improved measurement, various common subtypes of nonadherence, such as intentional versus accidental mistakes in timing or dosing, could be defined and these categories could be used to assign patients to appropriate interventions. Interventions that target motivation (20, 21) may be indicated for patients who intentionally stop taking medications, while those that emphasize reminders and behavioral reinforcements (17, 22) could be targeted to patients with cognitive deficits.

Although the various conceptual models (6–8) provide some guideposts for variables to be considered in future research, further theoretical development is needed. It is unlikely that we will learn sufficiently from research that is simply empirically driven and that does not build on the theoretical foundations available from varying approaches to behavioral change. While the importance of attaining adherence is widely recognized, it is typically seen as an individual treatment challenge rather than one that is amenable to contextual influences and various service strategies. The complexity of these influences also complicates theory development in this area.

The development of interventions to reduce nonadherence cannot overlook the risk factors associated with this behavior. Although knowledge about medications has not been consistently correlated with actual medication use, psychoeducation continues to be a cornerstone of many adherence interventions. In addition, a poor therapeutic alliance has been linked frequently to nonadherence; however, this knowledge has only recently been applied to interventions that seek to improve the therapeutic relationship and avoid confrontation (20, 21). The literature linking medication side effects to medication nonadherence suggests that the newer atypical antipsychotic medications, which generally have milder side effects profiles, may make adherence easier to achieve and maintain (71, 72), but nonadherence can still be substantial (73).

Our progress in understanding how to improve adherence lags well behind the striking advances in psychopharmacology. There are many shortcomings in the research, and it is apparent that no single strategy has yielded impressive results. Greater attention must be given to this common and often overlooked problem if we are to take full advantage of current pharmacological therapies.

|

|

|

|

|

Received June 29, 2001; revision received April 16, 2002; accepted April 18, 2002. From the Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research and the Center for Research on the Organization and Financing of Care for the Severely Mentally Ill, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J.; the Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University, New York; and New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York. Address reprint requests to Dr. Zygmunt, Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research, Rutgers University, 30 College Ave., New Brunswick, NJ 08901-1293; [email protected] (e-mail). This work was conducted at Rutgers University, Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, & Aging Research, Center for Research on the Organization and Financing of Care for the Severely Mentally Ill, 30 College Ave., New Brunswick, N.J. 08901-1293. Supported by NIMH grant MH-43450 (Dr. Mechanic).

1. Thornley B, Adams C: Content and quality of 2000 controlled trials in schizophrenia over 50 years. Br Med J 1998; 317:1181-1184Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Babiker IE: Noncompliance in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Dev 1986; 4:329-337Medline, Google Scholar

3. Weiden PJ, Olfson M: Cost of relapse in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1995; 21:419-429Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Young JL, Spitz RT, Hillbrand M, Daneri G: Medication adherence failure in schizophrenia: a forensic review of rates, reasons, treatments and prospects. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 1999; 27:426-442Medline, Google Scholar

5. Fenton WS, Blyler C, Heinssen RK: Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophr Bull 1997; 23:637-651Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Rosenstock IM: Why people use health services. Milbank Mem Fund Q 1966; 44:94-127Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Svarstad BL: Patient-practitioner relationships and compliance with prescribed medical regimens, in Applications of Social Science to Clinical Medicine and Health Policy. Edited by Aiken LH, Mechanic D. New Brunswick, NJ, Rutgers University Press, 1986, pp 438-459Google Scholar

8. Leventhal E, Robitaille C, Leventhal H, Brownlee S: Psycho-social factors in medication adherence: a model of the modler, in Processing of Medical Information in Aging Patients: Cognitive and Human Factors Perspectives. Edited by Park DC, Morrell R, Shifren K. Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1999, pp 145-165Google Scholar

9. Haynes RB, McKibbon KA, Kanani R: Systematic review of randomised trials of interventions to assist patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Lancet 1996; 348:383-386Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Haynes RB, McKibbon KA, Kanani R, Brouwers MC, Oliver T: Interventions to help patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, vol 2, 1999Google Scholar

11. Mojtabai R, Nicholson RA, Carpenter BN: Role of psychosocial treatments in management of schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review of controlled outcome studies. Schizophr Bull 1998; 24:569-587Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Razali SM, Hasanah CI, Khan A, Subramaniam M: Psychosocial interventions for schizophrenia. J Ment Health 2000; 9:283-289Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Strang JS, Falloon IR, Moss HB, Razani J, Boyd JL: The effects of family therapy on treatment compliance in schizophrenia. Psychopharmacol Bull 1981; 17:87-88Medline, Google Scholar

14. Xiang M, Ran M, Li S: A controlled evaluation of psychoeducational family intervention in a rural Chinese community. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 165:544-548Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Stein LI, Test MA: Alternative to mental hospital treatment, I: conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980; 37:392-397Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Guimon L, Eguiluz I, Bulbena A: Group pharmacotherapy in schizophrenics: attitudinal and clinical changes. Eur J Psychiatry 1993; 7:147-154Google Scholar

17. Kelly GR, Scott JA: Medication compliance and health education among outpatients with chronic mental disorders. Med Care 1990; 28:1181-1197Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Bush CT, Langford MW, Rosen P, Gott W: Operation outreach: intensive case management for severely psychiatrically disabled adults. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990; 41:647-649Abstract, Google Scholar

19. Sands RG, Cnaan RA: Two models of case management: assessing their impact. Community Ment Health J 1994; 30:441-457Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Kemp R, Hayward P, Applewhaite G, Everitt B, David A: Compliance therapy in psychotic patients: randomised controlled trial. Br Med J 1996; 372:345-349Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Kemp R, Kirov G, Hayward P, David A: Randomized controlled trial of compliance therapy—18-month follow-up. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 172:413-419Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Azrin NH, Teichner G: Evaluation of an instructional program for improving medication compliance for chronically mentally ill outpatients. Behav Res Ther 1998; 36:849-861Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Boczkowski JA, Zeichner A, DeSanto N: Neuroleptic compliance among chronic schizophrenic outpatients: an intervention outcome report. J Consult Clin Psychiatry 1985; 53:666-671Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Macpherson R, Jerrom B, Hughes A: A controlled study of education about drug treatment in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168:709-717Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Hornung WP, Kieserg A, Feldmann R, Buchkremer G: Psychoeducational training for schizophrenic patients: background, procedure and empirical findings. Patient Educ Couns 1996; 29:257-268Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Hornung WP, Klingberg S, Feldmann R, Schonauer K, Schulze Monking H: Collaboration with drug treatment by schizophrenic patients with and without psychoeducational training: results of a 1-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998; 97:213-219Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Buchkremer G, Klingberg S, Holle R, Schulze Monking H, Hornung WP: Psychoeducational psychotherapy for schizophrenic patients and their key relatives or care-givers: results of a 2-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997; 96:483-491Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Seltzer A, Roncari I, Garfinkel P: Effect of patient education on medication compliance. Can J Psychiatry 1980; 25:638-645Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Battle EH, Halliburton A, Wallston KA: Self medication among psychiatric patients and adherence after discharge. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 1982; 20:21-28Medline, Google Scholar

30. Atkinson JM, Coia DA, Gilmour WH, Harper JP: The impact of education groups for people with schizophrenia on social functioning and quality of life. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168:199-204Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Hogarty GE, Kornblith SJ, Greenwald D, DiBarry AL, Cooley S, Ulrich RF, Carter M, Flesher S: Three-year trials of personal therapy among schizophrenic patients living with or independent of family, I: description of study and effects on relapse rates. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1504-1513Link, Google Scholar

32. Streicker SK, Amdur M, Dincin J: Educating patients about psychiatric medications: failure to enhance compliance. Psychosoc Rehabil J 1986; 4:15-28Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Malm U: The influence of group therapy on schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1982; 297:1-65Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Falloon IR, McGill CW, Boyd JL, Pederson J: Family management in the prevention of morbidity of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:887-896Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Glick ID, Clarkin JF, Haas GL, Spencer JH: A randomized clinical trial of inpatient family intervention, VI: mediating variables and outcome. Fam Process 1991; 30:85-99Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Leff J, Kuipers L, Berkowitz R, Sturgeon D: A controlled trial of social interventions in the families of schizophrenia patients: two year follow-up. Br J Psychiatry 1985; 146:594-600Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Leff J, Berkowitz R, Shavit N, Strachan A, Glass I, Vaughn C: A trial of family therapy v a relatives group for schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 154:58-66Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Leff J, Berkowitz R, Shavit N, Strachan A, Glass I, Vaughn C: A trial of family therapy versus a relatives’ group for schizophrenia: two-year follow-up. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 157:571-577Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. McFarlane WR, Lukens E, Link B, Dushay R, Deakins SA, Newmark M, Dunne EJ, Horen B, Toran J: Multiple-family groups and psychoeducation in the treatment of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:679-687Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Schooler NR, Keith SJ, Severe JB, Matthews SM, Bellack AS, Glick ID, Hargreaves WA, Kane JM, Ninan PT, Frances A, Jacobs M, Lieberman JA, Mance R, Simpson GM, Woerner MG: Relapse and rehospitalization during maintenance treatment of schizophrenia: the effects of dose reduction and family treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:453-463Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Tarrier N: The community management of schizophrenia: a controlled trial of a behavioral intervention with families to reduce relapse. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 153:532-542Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Telles C, Karno M, Mintz J, Paz G, Arias M, Tucker D, Lopez S: Immigrant families coping with schizophrenia: behavioral family intervention v case management with a low-income Spanish-speaking population. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 167:473-479Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Xiong W, Phillips MR, Xiong H, Ruiwen W, Quinquing D, Kleinman J, Kleinman A: Family-based intervention for schizophrenic patients in China: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 165:239-247Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Zhang M, Wang M, Li J, Phillips MR: Randomised-control trial of family intervention for 78 first-episode male schizophrenic patients: an 18-month study in Suzhou, Jiangsu. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1994; 24:96-102Medline, Google Scholar

45. Marshall M, Lockwood A: Assertive community treatment for people with severe mental disorders (Cochrane review). Cochrane Library 2002; 2Google Scholar

46. Teague GB, Bond GR, Drake RE: Program fidelity in assertive community treatment: development and use of a measure. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1998; 68:216-232Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Bond GR, Miller LD, Krumwied RD, Ward RS: Assertive case management in three CMHCs: a controlled study. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1988; 39:411-418Abstract, Google Scholar

48. Ford R, Beadsmore A, Ryan P, Repper J, Craig T, Muijen M: Providing the safety net: case management for people with serious mental illness. J Ment Health 1995; 1:91-97Crossref, Google Scholar

49. Modrcin M, Rapp CA, Poertner J: The evaluation of case management services with the chronically mentally ill. Eval Program Plann 1988; 11:307-314Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Solomon P, Draine J: The efficacy of a consumer case management team: 2-year outcomes of a randomized trial. J Ment Health Adm 1995; 22:135-146Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Bigelow DA, McFarland BH, Gareau MJ, Young DJ: Implementation and effectiveness of a bed reduction project. Community Ment Health J 1991; 27:125-133Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Bond GR, Witheridge TF, Wasmer D, Dincin J, McRae SA, Mayes J, Ward RS: A comparison of two crisis housing alternatives to psychiatric hospitalization. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1989; 40:177-183Abstract, Google Scholar

53. Bond GR, McDonel EC, Miller LD, Pensec M: Assertive community treatment and reference groups: an evaluation of their effectiveness for young adults with serious mental illness and substance abuse problems. Psychosoc Rehabil J 1991; 15:30-43Google Scholar

54. Dixon L, Weiden P, Torres M, Lehman A: Assertive community treatment and medication compliance in the homeless mentally ill. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1302-1304Link, Google Scholar

55. Herz MI: Psychosocial treatment. Psychiatr Annals 1996; 26:531-535Crossref, Google Scholar

56. Hogarty GE, Anderson CM, Reiss DJ, Kornblith SJ, Greenwald DP, Javna CD, Madonia MJ: Family psychoeducation, social skills training, and maintenance chemotherapy in the aftercare treatment of schizophrenia, I: one-year effects of a controlled study on relapse and expressed emotion. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:633-642Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Hogarty GE, Anderson CM, Reiss DJ, Kornblith SJ, Greenwald DP, Ulrich RJ, Carter M: Family psychoeducation, social skills training, and maintenance chemotherapy in the aftercare treatment of schizophrenia, II: two-year effects of a controlled study on relapse and adjustment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:340-347Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Linszen D, Dingemans P, Van Der Does JW, Nugter A, Scholte P, Lenior R, Goldstein MJ: Treatment, expressed emotion, and relapse in recent onset schizophrenic disorders. Psychol Med 1996; 26:333-342Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Merinder LB, Viuff AG, Laugesen HD, Clemmensen K, Misfelt S, Espensen B: Patient and relative education in community psychiatry: a randomized controlled trial regarding its effectiveness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1999; 34:287-294Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Chan DW: Medication compliance in a Chinese psychiatric out-patient setting. Br J Med Psychol 1984; 57:81-89Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Razali SM, Hasanah CI, Khan UA: Belief in supernatural causes of mental illness among Malay patients: impact on treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996; 94:221-223Crossref, Google Scholar

62. Perkins RE, Repper JM: Compliance or informed choice. Br J Ment Health 1999; 2:117-129Google Scholar

63. Zimmerman RS, Olson K: AIDS-related risk behavior and behavior change in a sexually active, heterosexual sample: a test of three models of prevention. AIDS Educ Prev 1994; 6:189-204Medline, Google Scholar

64. Smith A, Mucklow JC, Wandless I: Compliance with drug treatment. Br Med J 1979; 1:1335-1336Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65. Epstein LH, Cluss PA: A behavioral medicine perspective on adherence to long-term medical regimes. J Consult Clin Psychol 1982; 50:950-971Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

66. Kelly KA: HIV risk reduction interventions for persons with severe mental illness. Clin Psychol Rev 1997; 17:293-309Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67. Olfson M, Mechanic D, Hansell S, Boyer CA, Walkup J, Weiden PJ: Predicting medication noncompliance after hospital discharge among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2000; 51:216-222Link, Google Scholar

68. Marengo JT, Harrow M: Longitudinal courses of thought disorder in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr Bull 1997; 23:273-285Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

69. Weiden PJ, Dixon L, Frances A, Appelbaum P, Haas G, Rankin B: Neuroleptic noncompliance in schizophrenia, in Advances in Neuropsychiatry and Psychopharmacology: Schizophrenia Research, vol 1. Edited by Tamminga CA, Schulz SC. New York, Raven Press, 1991, pp 285-296Google Scholar

70. Cramer JA, Rosenheck R: Enhancing medication compliance for people with serious mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis 1999; 187:53-55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71. Leucht S, Pitschel-Walz G, Abraham D, Kissling W: Efficacy and extrapyramidal side-effects of the new antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and sertindole compared to conventional antipsychotics and placebo: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Res 1999; 35:51-68Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

72. Rosenheck R, Chang S, Choe Y, Cramer J, Xu W, Thomas J, Henderson W, Charney D: Medication continuation and compliance: a comparison of patients treated with clozapine and haloperidol. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:382-386Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

73. Dolder CR, Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Jeste DV: Antipsychotic medication adherence: is there a difference between typical and atypical agents? Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:103-108Link, Google Scholar