A Double-Blind Comparative Study of Clozapine and Risperidone in the Management of Severe Chronic Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This prospective, double-blind, multicenter, parallel-group study compared the efficacy and safety of therapeutic doses of clozapine and risperidone in patients with severe chronic schizophrenia and poor previous treatment response. METHOD: Male or female patients aged 18–65 years who met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia and study requirements for poor previous treatment response (N=273) were randomly assigned to double-blind treatment with either clozapine or risperidone administered over 12 weeks in increasing increments. The primary efficacy measures were the magnitude of improvement in Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scores. Adverse events were recorded throughout the study. RESULTS: The magnitude of improvement in mean BPRS and CGI scores from baseline to end of the study was significantly greater in the clozapine group than in the risperidone group. Statistically significant differences in favor of clozapine were also seen for most of the secondary efficacy measures (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, Calgary Depression Scale, Psychotic Depression Scale, and Psychotic Anxiety Scale). The adverse event profile was similar for both treatment groups, with a lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms in the clozapine group. CONCLUSIONS: Clozapine showed superior efficacy over risperidone in this patient population. Both treatments were equally well tolerated as demonstrated through their adverse event profiles, although as expected clozapine was associated with a lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms than risperidone.

Clozapine was the first major advance in the treatment of schizophrenia since the introduction of the classic antipsychotic agents chlorpromazine and haloperidol in the 1950s (1). Improved efficacy against the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia (2–5), a low propensity to cause extrapyramidal symptoms in both the short and long term (5–7), together with a lack of clinically relevant effects on serum prolactin (8) distinguished it from the classic agents and led to the concept of the “atypical” antipsychotic (9). The publication of two landmark comparative trials in the late 1980s unequivocally demonstrated the efficacy of clozapine for patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia (2, 10). In their 6-week, double-blind study of 268 patients who met strict criteria for treatment-resistance, Kane et al. (2) demonstrated that clozapine was significantly more effective than chlorpromazine (response rates of 30% and 4%, respectively; p<0.001). A more recent double-blind comparison of clozapine with haloperidol in 423 hospitalized patients with refractory schizophrenia showed that at follow-up, patients in the clozapine group had significantly lower symptom levels than did those in the haloperidol group (p=0.02) (3). The results from these trials have established clozapine’s position as the “gold standard” therapy for treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

Over the past 10 years, clozapine has become the reference compound for the development of new antipsychotics, and recently several new drugs have been developed with the hope that they will share the “atypical” properties of clozapine without the requirement for regular hematologic monitoring. Of these, risperidone has been the most widely studied. Risperidone has shown efficacy comparable or superior to that of haloperidol against positive and negative symptoms in short-term, fixed-dose studies of patients with acute and chronic schizophrenia (11–13). Speculation that the drug will also be effective in patients with treatment-resistant disease has been fueled by the finding of efficacy in a subgroup of patients from one of the pivotal trials that had not responded well to conventional neuroleptics over a prolonged period (14). However, direct comparisons of its efficacy with that of clozapine, derived from inadequately designed trials (15–17), have been inconclusive. The methods used in these trials have been criticized on the basis of several parameters, including insufficient sample size (15–17), open design (16), and use of suboptimal clozapine dosages (15) (for review, see reference 18).

To our knowledge, the present study is the first methodologically robust study of adequate size and duration to compare the efficacy and safety of therapeutic doses of clozapine and risperidone in patients with severe chronic schizophrenia and poor previous treatment response, which was chosen instead of treatment resistance to have patients more representative of those seen in current clinical practice.

Method

This prospective, double-blind, parallel-group study was conducted at 41 centers in France (N=29) and Canada (N=12) between October 1994 and January 1996, in accordance with the World Health Organization’s Good Clinical Research Practice Guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki (19). Local ethics committee approvals were obtained, and subjects gave their written informed consent after complete description of the study.

Patients

Male and female patients aged 18–65 years who met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia (disorganized, catatonic, paranoid, residual, or undifferentiated) were eligible for recruitment. Only those with baseline scores of at least 4 on the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale (20), at least 45 (total score) on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (21), and at least 4 on two or more of the four core symptoms (unusual thought content, hallucinations, conceptual disorganization, suspiciousness) were randomly assigned to treatment with either clozapine or risperidone. Both inpatients and outpatients were recruited to the study.

Patients were excluded if they had a history of medical conditions or drug treatment that might put them at special risk or bias the assessment of their clinical or mental status (e.g., epilepsy requiring continuous treatment, active blood dyscrasias, leukopenia, chronic obstructive lung disease or pulmonary emphysema, cardiovascular disease or recent myocardial infarction, significantly impaired renal or hepatic function, active problems with urinary retention or narrow angle glaucoma, toxic psychosis, chemical dependence, or moderate to severe mental retardation). Those previously treated with clozapine or risperidone were excluded from the trial. Patients likely to require continuous treatment with other psychotropic agents, anticholinergics, or drugs likely to lower white blood cell count were also excluded, as were women of childbearing potential who were not practicing a medically approved form of birth control.

Poor Previous Treatment Response

Patients were additionally required to meet the following minimum criteria for poor response to previous treatment.

1. The patient’s current episode had been treated continually with a neuroleptic for at least the preceding 6 months without significant clinical improvement.

2. The patient had undergone one unsuccessful trial of antipsychotic medication equivalent to 20 mg/day of haloperidol for at least 6 weeks (less if the patient was experiencing dose-limiting adverse events) since the onset of the current episode. If several drugs had been prescribed simultaneously, the final equivalence dosage could be calculated by adding the individual equivalencies.

3. The patient had experienced no period of good functioning for at least 24 months despite a sufficient period of use of two antipsychotics from at least two chemical classes, or no period of good functioning for 5 years despite the use of three antipsychotics.

Poor previous treatment response as defined in the current study differs from treatment resistance by having a less stringent criterion for the previous drug history than did the study by Kane et al. (2), enabling patients to be more representative of those seen in current clinical practice compared with previous clinical trials.

Study Design

The study was divided into three periods. In the first period, a screening examination (consisting of a review of medical and drug histories, physical and laboratory examinations, and an electrocardiogram) was followed by a single-blind placebo run-in of at least 3 days during which all psychotropic and anticholinergic medication was withdrawn. For patients treated with depot neuroleptics, the placebo period started on the day they would otherwise have received their next injection. Patients who satisfied the eligibility criteria were then randomly assigned to double-blind treatment (balanced by country, with a block size of six) with either clozapine or risperidone on a twice-daily basis.

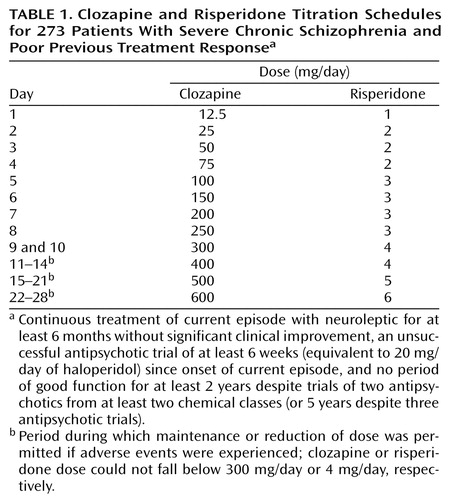

In the second period, study drug dose was titrated over 4 weeks according to a fixed schedule (Table 1). Starting daily doses of 12.5 mg for clozapine and 1 mg for risperidone were increased to 300 mg/day and 4 mg/day, respectively, over 9 days; patients unable to tolerate these doses on the 10th day were withdrawn from the study. Further incremental increases to 600 mg/day and 6 mg/day, respectively, were scheduled, but if dose-limiting adverse events were experienced, the dose could be maintained or reduced without necessitating withdrawal from the study, provided that the clozapine or risperidone dose did not fall below 300 mg/day or 4 mg/day, respectively.

The third period was an 8-week, flexible-dose period during which the daily dose was adjusted clinically at 2-week intervals within the range of 200–900 mg/day for clozapine or 2–15 mg/day for risperidone. An increase in dose was recommended if response criteria were not reached. Prescription of any antipsychotic other than the study drug was prohibited for the duration of the study.

Efficacy Assessments

The primary efficacy measures were the magnitude of improvement in BPRS and CGI scores. The BPRS was extracted from 18 items of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, an evaluation scale of 30 items scored from 1 (normal) to 7 (severely ill) (22). Treatment response was explored by using the criteria of an improvement in BPRS total score of 20%, 30%, 40%, or 50% and also by the definition of Kane et al. (2) (reduction of ≥20% in BPRS total score together with either a posttreatment CGI ≤3 or a posttreatment BPRS total score ≤35). Secondary efficacy measures included the total, positive symptom, negative symptom, and general psychopathology scores of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, the Psychotic Anxiety Scale (23), Psychotic Depression Scale (24), and the Calgary Depression Scale (25). A psychiatric interview was performed at baseline; primary efficacy measures were administered every 2 weeks and secondary measures every 4 weeks throughout the study.

Safety Assessments

Blood counts were performed weekly, and vital signs were measured daily for the first 11 days and then on days 14, 15, 22, 28 and every 2 weeks thereafter. Extrapyramidal symptoms rated by the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (26) were recorded every 2 weeks. Adverse events were recorded throughout the study.

Statistical Analysis

Initial calculations indicated that 150 patients per treatment group were required to guarantee power of 0.90 in detecting a difference (alpha=0.05) when comparing therapies with underlying success rates of 40% and 20%. Power was reduced to 0.70 when comparing success rates of 35% and 20%.

Three patient populations were defined for the purposes of analysis. The safety population comprised all patients who received at least one dose of study medication and had at least one postdose safety assessment. The intent-to-treat population consisted of all randomly assigned patients with at least one postdose BPRS evaluation. The per-protocol population comprised all patients in the intent-to-treat population who completed the first 28 days of the study without major protocol violation (i.e., insufficient documentation of poor response to treatment, prior treatment with either clozapine or risperidone, or inadequate dosing at day 28). Both intent-to-treat and per-protocol populations were described in the efficacy analysis, with intent-to-treat being the population of primary interest.

The primary endpoint for efficacy analysis was the end of the third period (i.e., after 12 weeks of treatment), obtained by carrying forward the last observation in the study for each patient. A secondary endpoint was the end of the second period, obtained by carrying forward the last observation up to the end of the titration schedule (week 4) for each patient. Data were also described at each visit, from baseline to week 12, based on observed cases at the visit of interest. Descriptive statistics were presented and the two treatment groups were compared at each of these time points; however, p values at individual visits are purely exploratory.

Randomization was designed to be balanced by country, not by center, as there were a large number of centers that recruited very few patients, making it difficult to control for a possible center effect. Control for country effect and its interaction with treatment were investigated through response rates per the definition of Kane et al. (2). A sensitivity analysis was carried out on centers that had recruited at least six patients and used the same criteria. Control for language (French versus American English) was not addressed because 84% of patients were French speaking.

Response rates, per the definition of Kane et al. (2), were compared between treatment groups at the end of the second and third periods by using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, adjusting for country. The treatment-by-country interaction was tested by means of the Breslow-Day pseudohomogeneity test, based on the Mantel-Haenszel statistic, for the intent-to-treat population at the end of the third period.

In terms of other efficacy measures, improvements from baseline in quantitative variables (total and subscale scores of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, BPRS core item scores, CGI score, Calgary Depression Scale, Psychotic Anxiety Scale, and total and subscale scores of the Psychotic Depression Scale) were analyzed by means of t tests. For BPRS total score, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with treatment as factor and baseline value as covariate was used because of the initial imbalance between the two treatment groups. Chi-square tests were used for between-group comparisons on qualitative criteria (20%–50% decrease in BPRS score, 1–2 point decrease in CGI score, 20%–50% decrease in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale score).

The frequency of newly occurring adverse events was compared between treatment groups by using Fisher’s exact test for events reported by more than five patients (within the safety population). Episodes of hypotension (diastolic blood pressure <50 mm Hg or systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg) were analyzed by means of frequency tables.

ANCOVA was used to assess the change from baseline in Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale score at the end of the study (with treatment factor and baseline as a covariate), while chi-square tests were used in analyzing frequency tables of the proportion of improved/worsened/unchanged patients by treatment group. Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale evaluations were censored at first intake of anticholinergic medication; patients with no symptoms (scores of zero) from baseline to the end of study were not taken into account in the analysis.

Results

Patients

A total of 273 patients were randomly assigned to one of the two treatment groups (clozapine, N=138; risperidone, N=135), and 201 patients completed the study (clozapine, N=100; risperidone, N=101). Reasons for premature discontinuation are shown in Table 2. Demographic and baseline characteristics for the intent-to-treat and per-protocol populations are shown in Table 3. Except for the BPRS scores, which were significantly higher in the clozapine group, there were only minor differences between the two treatment groups in terms of chronicity and severity of disease. Patients in the clozapine group tended to have a greater number of previous episodes and hospitalizations, while those in the risperidone group tended to have a longer duration of disease and time since last episode of good function.

At the end of the 8-week flexible dose period, median daily doses of clozapine and risperidone were 600 mg and 6 mg, respectively, for the intent-to-treat population. For patients who completed all 12 weeks of the study, median final daily doses were 600 mg and 9 mg, respectively. Dosages for the per-protocol population were comparable. On an observed-patient basis, the mean dose for patients completing the study was 642 mg/day (SD=212) for clozapine and 9 mg/day (SD=4) for risperidone.

Efficacy

Magnitude of response, as determined by mean changes in the primary efficacy measures (BPRS total score and CGI score) from baseline to end of study, was significantly greater in the clozapine group than in the risperidone group for both the intent-to-treat and per-protocol populations (Table 4). For the per-protocol population, the significant difference between treatments emerged at week 6 and was maintained at all subsequent time points. Statistically significant differences in favor of clozapine in terms of changes from baseline to end of study were seen for most of the secondary efficacy measures (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total and subscale scores, Psychotic Anxiety Scale score) for both the intent-to-treat and per-protocol populations (Table 5). Absolute values for the Calgary Depression Scale significantly favored clozapine at the end of the study (baseline scores were similar). For the Psychotic Depression Scale, the total score and psychotic and mood subscale scores were significantly reduced from baseline for the per-protocol population (Table 5).

An exploratory analysis to examine the efficacy of the treatments in those patients who had completed 12 weeks from baseline was carried out. In the intent-to-treat population, changes in the BPRS (ANCOVA F=2.54, df=1, 199, p=0.10) and CGI score (t=1.54, df=201, p=0.10) were not significant, but those for the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale were (t=2.08, df=195, p=0.04). In the per-protocol population, all changes in efficacy measures were significant: BPRS (ANCOVA F=4.20, df=1, 167, p=0.04), CGI (t=2.02, df=169, p=0.04), and Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (t=2.32, df=163, p=0.02).

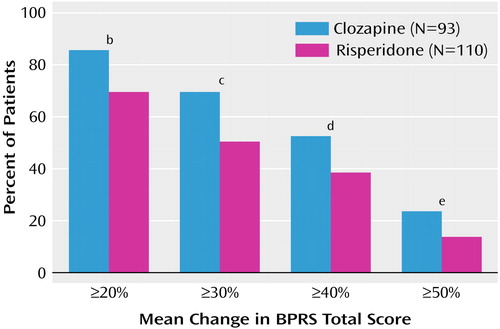

The proportions of patients with decreases in mean BPRS total score of ≥20% and ≥30% at the end of the study were significantly higher in the clozapine group than in the risperidone group for both the intent-to-treat and per-protocol populations (Figure 1), as was the proportion of patients with decreases of ≥40% in the per-protocol population. At study close, per the criteria of Kane et al. (2), 61 patients (48.4%) in the clozapine intent-to-treat group and 56 (43.1%) in the risperidone intent-to-treat group were classified as responders (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test: χ2=0.78, df=1, p<0.38). There was no effect on treatment by country (Breslow-Day pseudohomogeneity test statistic=1.34, df=1, p=0.25). The response rates calculated for the per-protocol population were 53.8% (N=50) for the clozapine group and 44.5% (N=49) for the risperidone group (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test: χ2=1.65, df=1, p<0.20). A sensitivity analysis carried out on centers with at least six patients recruited to the study showed similar results: 39 (52.7%) out of 74 patients were classified as responders, per the criteria of Kane et al. (2), in the clozapine group compared with 33 (42.9%) out of 77 patients in the risperidone group (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test: χ2=1.31, df=1, p<0.23). Overall, at the end of the study, 94 (75.8%) patients in the clozapine group and 81 (64.3%) patients in the risperidone group no longer met the severity of psychopathology inclusion criteria (χ2=3.95, df=1, p<0.05).

Significantly more patients in the risperidone group withdrew from the study because of treatment failure (Table 2). However, no difference in the time to study discontinuation was observed between the two groups (t=0.56, df=271, p=0.57).

Tolerability

Withdrawals due to adverse events occurred with similar frequency in both treatment groups (Table 2). Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 78.7% (N=107) of patients in the clozapine group and 82.8% (N=111) of patients in the risperidone group (p=0.44, Fisher’s exact test). In terms of individual adverse events, convulsions, dizziness, sialorrhea, tachycardia, and somnolence occurred significantly more frequently in the clozapine group, whereas extrapyramidal symptoms and insomnia occurred significantly more frequently in the risperidone group (Table 6). Dry mouth was also significantly greater in the risperidone group, although the incidence was <5% (clozapine 0%, risperidone 4%).

The results of two Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale subscales favored clozapine: reduction from baseline for CGI parkinsonism score (ANCOVA F=4.82, df=1, 167, p<0.03) and improvement/worsening of hyperkinesia (χ2=6.08, df=2, p<0.05).

Granulocytopenia reported as an adverse event occurred with a similar low incidence in both treatment groups (1% clozapine, 2% risperidone), whereas low neutrophil counts (<2000/mm3) detected by routine laboratory analysis were significantly more frequent in the risperidone group (clozapine: 2.9%, risperidone: 11.2%; p<0.01, Fisher’s exact test). Low leukocyte counts (<3500/mm3) occurred with a similar low incidence in both treatment groups (clozapine: 0.7%, risperidone: 3.7%; p<0.12, Fisher’s exact test), but significantly more patients in the risperidone group had leukocytes reduced by 50% or more between two consecutive evaluations (clozapine: 2.2%, risperidone: 5.2%; p<0.01, Fisher’s exact test). No case of agranulocytosis was observed during the study.

The incidence of convulsions was significantly higher in the clozapine group (Table 6) and was higher than expected in both groups. Of the 12 convulsions reported in conjunction with clozapine therapy, 10 occurred at high doses (in excess of 600 mg/day).

While there was no significant difference between treatment groups in the incidence of hypotension reported as an adverse event (Table 6), hypotension detected from measurement of vital signs (systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure <50 mm Hg) was significantly more frequent in the risperidone group (clozapine: 2.9%, risperidone: 11.2%; p<0.01, Fisher’s exact test). The increase in mean body weight from baseline to the end of study was significantly greater for the clozapine treatment group (clozapine: 2.4 kg, risperidone: 0.2 kg; t=3.14, df=198, p<0.002).

Discussion

The magnitude of response, determined by the change in both primary efficacy measures (total BPRS and CGI scores), was significantly in favor of clozapine irrespective of the population under evaluation. Similarly, response was significantly greater in the clozapine group for the majority of secondary efficacy measures, with the exception of the Psychotic Depression Scale (where significant differences were found for the per-protocol population only) and the Calgary Depression Scale.

The superiority of clozapine in improving Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total and subscores and CGI scores confirms the preliminary results of an open comparison of clozapine and risperidone in 86 patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia for a mean treatment duration of 12 weeks (16). Although the previous trial was small in size and of open design, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total and positive subscores, general psychopathology subscores, and CGI score showed significantly greater improvement with clozapine than risperidone.

Although the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale and CGI efficacy data from both this present study and that of Flynn et al. (16) contrast with data from an earlier comparative 8-week study (15), this latter study has received strong criticism for its design. First, because of its small sample size (N=86), it lacked the power to show a statistical difference between the two drugs. Furthermore, the target dose chosen for clozapine in the titration period (300 mg) was too low, and plasma levels were lower than those found to be optimal in previous studies (27–29). The use of a subtherapeutic dose of clozapine by Bondolfi et al. (15) is likely to explain why the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale score changes reported in their study for clozapine were markedly lower than those reported in this present study (–23.2 versus –37.5, respectively), while risperidone-treated patients had similar Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale score changes (–27.4 versus –29.9, respectively). Finally, the authors acknowledged that the 8-week duration of treatment may not have been sufficient to achieve optimal response.

During the study, there was an increase in antipsychotic dosage for risperidone while the clozapine dosage remained constant. This was a consequence of the protocol guidelines in which the dosage had to be increased if the response criteria were to be reached (decrease of BPRS >20%). These criteria were attained more often in the clozapine group. The dosing titration schedule employed for risperidone was in keeping with the current thinking at the time that this trial was designed (1994). The upper dosage of risperidone may also, in terms of current practice, be considered slightly high. However, it is common for patients with more treatment-resistant forms of schizophrenia to be treated with a higher medication dosage (30). Although there were no significant differences between the groups in favor of risperidone, risperidone was effective in treating the symptoms of schizophrenia, with improvements from baseline in both the BPRS and CGI scores (Table 4).

According to the most usual measure of response in severe chronic schizophrenia, ≥20% reduction in BPRS total score, the response rate in the present study was significantly in favor of clozapine. The respective figures for responders were 86.0% for clozapine and 70.0% for risperidone (Figure 1). Furthermore, a significant difference in favor of clozapine was also apparent when the proportion of patients with decreases in mean BPRS total score of ≥30% and ≥40% were evaluated. Similarly, per the criteria of Kane et al. (2), there was a nonsignificant difference in favor of clozapine. However, the response rate for clozapine in the present study may appear higher than the response rate of 30% seen in the pivotal study of Kane et al. (2), and the 31% rate of response (defined as ≥20% reduction in symptoms) seen at the equivalent time point in the Veterans Affairs study (3). This inconsistency probably reflects the different inclusion criteria used in the present study, chosen to recruit patients more representative of those seen in clinical practice. Clozapine is not used in clinical practice in Europe and Canada at a dose equivalent to 1000 mg of chlorpromazine. The criteria for treatment resistance in this study were in accordance with clozapine labeling in France. Hence, this study was more likely to include patients with severe chronic schizophrenia with a poor treatment response rather than those with treatment resistance, as evaluated by the two earlier studies (2, 3). Poor response to treatment in the current study was verified with an unsuccessful prospective treatment with 60 mg of haloperidol. It must also be noted that since the BPRS total score in the present study was extracted from the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, these results are not directly comparable to those of the study by Kane et al. (2).

Both treatments were generally well tolerated and there were no significant between-group differences either in withdrawals due to adverse events or in the proportion of patients experiencing at least one adverse event. The types of adverse events experienced were consistent with the known side effect profiles of the two drugs. As expected, the incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms in the clozapine group was significantly lower than that reported in the risperidone group. A subsequent detailed review revealed that of the cases of extrapyramidal symptoms diagnosed, 72% of those reported in association with clozapine therapy were deemed to be transient compared with 58% in the risperidone group. It is likely that for both treatment groups, too short a duration of neuroleptic washout (3 days versus 2 weeks in the study by Kane et al. [2]) may have been responsible for the occurrence of residual extrapyramidal symptoms during the initial treatment phase. Results from two controlled studies of psychosis related to Parkinson’s disease have provided conclusive confirmation of the mildness of the extrapyramidal impact of clozapine (31, 32). The lack of any significant difference in the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale hypokinesia subscale in the current study can perhaps be explained by an incorrect assessment of sialorrhea; scoring should have been restricted to cases of sialorrhea as a consequence of facial rigidity, but this was not the case. Sialorrhea is also included as a factor in the hypokinesia score. As a result, there may have been a degree of potential bias for both subscores and for total use. The incidence of seizures was significantly higher in the clozapine group and higher than expected in both groups, which may be a reflection of the dosage used or the speed of titration; the 9% incidence seen in the clozapine group is comparable with the 7% incidence found in an analysis of clinical trials in the United States, where the average daily dose of clozapine was 444 mg (33). Of the 12 convulsions reported in conjunction with clozapine therapy, 10 occurred at doses in excess of 600 mg/day. Agranulocytosis was not reported, and hematologic toxicity was comparable in both treatment groups. Hypotension was noted significantly more frequently in the risperidone group.

Conclusions

In this population of patients with severe chronic schizophrenia and poor previous treatment response, clozapine exhibited clear therapeutic superiority over risperidone for the majority of efficacy measures. Both atypical antipsychotics were equally well tolerated and demonstrated their expected adverse event profiles, although, as expected, clozapine was associated with less risk of extrapyramidal symptoms but a higher risk of convulsions than risperidone.

Acknowledgments

The French/Canadian Clozapine Study Group involved the participation of the following investigators: (France) O. Blin, D. Bonnaffoux, R. Bouquet, P. Bujon-Pinard, P. Calvet, H. Chevrier-Garrigoux, R. De Beaurepaire, C. De Brito, V. Dreyfus, J.M. Dubroca, M. Fortier, J.C. Galidie, F. Gekiere, I. Jalenques, F. Khidichian, B. Lachaux, J. Louvrier, J. Monié, M. N’Guyen, M. Passamar, F. Petitjean, J.P. Provoost, J. Tignol, Y. Tyrode, and M.A. Zimmerman; (Canada) D. Addington, S. Altman, S. Beshai, E. Chow, D. Cliché, A. Labelle, W. Lit, J. Meller, L.K.O. Oyewumi, P. Silverstone, and E. Stip.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Received Feb. 8, 2000; revision received Nov. 16, 2000; accepted Dec. 21, 2000. From the French/Canadian Clozapine Study Group. Address reprint requests to Dr. Azorin, Hôpital St Marguerite, 270 Boulevard Ste Marguerite, 13274 Marseille, Cedex 09, France; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a grant from Novartis Pharma S.A.

Figure 1. Improvement in Total BPRS Score for Patients With Severe Chronic Schizophrenia and Poor Previous Treatment Responsea After 12 Weeks of Clozapine or Risperidone Therapy Among Those Receiving Adequate Doses After 28 Days (Per-Protocol Population)

aContinuous treatment of current episode with neuroleptic for at least 6 months without significant clinical improvement, an unsuccessful antipsychotic trial of at least 6 weeks (equivalent to 20 mg/day of haloperidol) since onset of current episode, and no period of good function for at least 2 years despite trials of two antipsychotics from at least two chemical classes (or 5 years despite three antipsychotic trials)

bSignificant difference between groups (χ2=7.38, df=1, p<0.01).

cSignificant difference between groups (χ2=7.54, df=1, p<0.01).

dSignificant difference between groups (χ2=3.76, df=1, p<0.05).

eNearly significant difference between groups (χ 2=3.39, df=1, p<0.06).

1. Johnson AL, Johnson DAW: Peer review of “Risperidone in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia: a multi-national, multi-centre, double-blind, parallel-group study versus haloperidol.” Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:727-733Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H: Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic: a double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:789-796Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Rosenheck R, Cramer J, Xu W, Thomas J, Henderson W, Frisman L, Fye C, Charney D (Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Clozapine in Refractory Schizophrenia): A comparison of clozapine and haloperidol in hospitalized patients with refractory schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:809-815Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Miller DD, Perry PJ, Cadoret RJ, Andreasen NC: Clozapine’s effect on negative symptoms in treatment-refractory schizophrenics. Compr Psychiatry 1994; 35:8-15Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Buchanan RW: Clozapine: efficacy and safety. Schizophr Bull 1995; 21:579-591Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Borison RL: Clinical pharmacology of clozapine (abstract). Pharmacology 1984; 26:179Google Scholar

7. Gerlach J, Peacock L: Intolerance to neuroleptic drugs: the art of avoiding extrapyramidal syndromes. Eur Psychiatry 1995; 10(suppl 1):27S-31SGoogle Scholar

8. Casey DE: Side effect profiles of new antipsychotic agents. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 1):40-45Google Scholar

9. Kinon BJ, Lieberman JA: Mechanisms of action of atypical antipsychotic drugs: a critical analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996; 124:2-34Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Claghorn J, Honigfeld G, Abuzzahab FS Sr, Wang R, Steinbook R, Tuason V, Klerman G: The risks and benefits of clozapine versus chlorpromazine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1987; 7:377-384Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Chouinard G, Jones B, Remington G, Bloom D, Addington D, MacEwan GW, Labelle A, Beauclair L, Arnott W: A Canadian multicenter placebo-controlled study of fixed doses of risperidone and haloperidol in the treatment of chronic schizophrenic patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1993; 13:25-40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Marder SR, Meibach RC: Risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:825-835Link, Google Scholar

13. Peuskens J (Risperidone Study Group): Risperidone in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia: a multi-national, multi-centre, double-blind, parallel-group study versus haloperidol. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:712-726Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Gutierrez-Esteinou R, Grebb JA: Risperidone: an analysis of the first three years in general use. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 12(suppl 4):S3-S10Google Scholar

15. Bondolfi G, Dufour H, Patris M, May JP, Billeter U, Eap CB, Baumann P: Risperidone versus clozapine in treatment-resistant chronic schizophrenia: a randomized double-blind study. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:499-504Link, Google Scholar

16. Flynn SW, MacEwan GW, Altman S, Kopala LC, Fredrikson DH, Smith GN, Honer WG: An open comparison of clozapine and risperidone in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Pharmacopsychiatry 1998; 31:25-29Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Breier AF, Malhotra AK, Su TP, Pinals DA, Elman I, Adler CM, Lafargue RT, Clifton A, Pickar D: Clozapine and risperidone in chronic schizophrenia: effects on symptoms, parkinsonian side effects, and neuroendocrine response. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:294-298Abstract, Google Scholar

18. Fleischhacker WW: Clozapine: a comparison with other novel antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60(suppl 12):30-34Google Scholar

19. Declaration of Helsinki: Recommendations Guiding Medical Doctors in Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects. Adopted by the 18th World Medical Assembly, Helsinki, Finland, June 1964, and amended by the 29th World Medical Assembly, Tokyo, Japan, October 1975, the 35th World Medical Assembly, Venice, Italy, October 1983, and the 41st World Medical Assembly, Hong Kong, September 1989Google Scholar

20. Guy W, Bonato R (eds): Manual for the ECDEU Assessment Battery, 2nd ed. Chevy Chase, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1970Google Scholar

21. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 1962; 10:799-812Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987; 13:261-276Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Blin O, Azorin JM, Lecrubier Y, Souche A, Fondarai J: The Psychotic Anxiety Scale (PAS): evaluation of inter-rater reliability and correspondence factorial analysis. Encephale 1989; 15:543-547Medline, Google Scholar

24. Azorin JM, Philippot P, Blin O: Discrimination between depressive, positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia: construction and study validation of the Psychotic Depression Scale (abstract). Neuropsychopharmacology 1994; 10(suppl 2):56SGoogle Scholar

25. Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E: Assessing depression in schizophrenia: the Calgary Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1993; 22:39-44Medline, Google Scholar

26. Chouinard G, Ross-Chouinard A, Annabel L, Jones BD: The Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (letter). Can J Neurol Sci 1980; 7:233Google Scholar

27. Kane JM: Treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 9):35-40Google Scholar

28. Potkin SG, Bera R, Gulasekaram B, Costa J, Hayes S, Jin Y, Richmond G, Carreon D, Sitanggan K, Gerber B: Plasma clozapine concentrations predict clinical response in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55(Sept suppl B):133-136Google Scholar

29. Miller DD: The clinical use of plasma clozapine concentrations in the management of treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1996; 8:99-109Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Marder SR: An approach to treatment resistance in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 37(suppl):19-22Google Scholar

31. The French Clozapine Parkinson Study Group: Clozapine in drug-induced psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 1999; 353:2041-2042Google Scholar

32. The Parkinson Study Group: Low-dose clozapine for the treatment of drug-induced psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med 1999; 340:757-763Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Fleischhacker WW, Hummer M, Kurz M, Kurzthaler I, Lieberman JA, Pollack S, Safferman AZ, Kane JM: Clozapine dose in the United States and Europe: implications for therapeutic and adverse effects. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55(Sept suppl B):78-81Google Scholar