Right Prefrontal Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The efficacy of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) of the right prefrontal cortex for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) was studied under double-blind, placebo-controlled conditions. METHOD: Patients were randomly assigned to 18 sessions of real (N=10) or sham (N=8) rTMS. Treatments lasted 20 minutes, and the frequency was 1 Hz for both conditions, but the intensity was 110% of motor threshold for real rTMS and 20% for the sham condition. RESULTS: No significant changes in OCD were detected in either group after treatment. Two patients who received real rTMS, with checking compulsions, and one receiving sham treatment, with sexual/religious obsessions, were considered responders. CONCLUSIONS: Low-frequency rTMS of the right prefrontal cortex failed to produce significant improvement of OCD and was not significantly different from sham treatment. Further studies are indicated to assess the efficacy of rTMS in OCD and to clarify the optimal stimulation characteristics.

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) has been proposed as therapeutic for different psychiatric disorders, mainly depression, although the stimulation characteristics are still controversial (1–3). Concerning obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), Greenberg et al. (4) reported a significant reduction in compulsions during and 8 hours after a single session of right prefrontal rTMS.

This study was designed to assess whether prolonged stimulation of the right prefrontal cortex at low frequency would produce significant improvement in a group of OCD patients under double-blind, placebo-controlled conditions.

Method

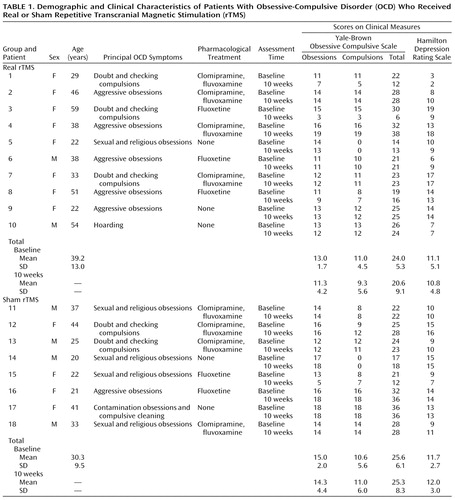

The study participants were 18 right-handed outpatients (12 female; mean age=35.2 years, SD=12.1) who met the DSM-IV criteria for OCD. Five of them were unmedicated, and the rest had been receiving stable pharmacological treatment for 12 weeks: fluoxetine, 80 mg/day (N=5), or clomipramine, 225 mg/day, combined with fluvoxamine, 300 mg/day (N=8) (Table 1). No patient met the DSM-IV criteria for any other axis I disorder. Individuals with a history of seizure or head trauma were not included. All patients gave written informed consent after complete description of the study.

The subjects were randomly assigned to real or sham rTMS and were blind to the expected effects of each condition. The rTMS was performed by using a Magstim Rapid stimulator (Magstim Company, Ltd., Whitland, U.K.). The brain target was the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. To encompass this relatively wide area, we used a 70-mm circular coil. Its distal end was positioned flat over the cortex superior to the inferior frontal sulcus and anterior to the precentral sulcus, centered over Brodmann areas 9 and 46 but also influencing areas 6, 8, 10, 44, and 45. Three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) models were used to establish the proper position of the coil. The MRI anatomical references were transposed to the patient’s head by using measured distances from the sulci scalp projection to external head landmarks. The sulci position was permanently marked for each patient by using an individualized cap.

The patients received 18 sessions (three sessions per week for 6 weeks), at a frequency of 1 Hz; each session lasted 20 minutes. For real rTMS, the intensity was 110% of the motor threshold. Motor threshold was determined over the right motor cortex by finding the minimum intensity that produced a visible motor response in the left thumb. Although high-intensity stimulation at low frequency has recently shown antidepressant effects with a lower risk of seizure induction (5), large numbers of sessions have rarely been tested in terms of safety. Consequently, we decided to administer rTMS three times per week instead of the more usual daily rate.

For sham treatment the coil was placed over the same area, perpendicular to the scalp. Patients received 18 sessions at 1 Hz, albeit with an intensity of 20% of the motor threshold. The rTMS was performed by a trained technician blind to the expected effects of each treatment condition. He was told which stimulation characteristics should be applied to each subject by one of the investigators (J.P.), who determined the threshold.

Assessments were performed at baseline and weekly until 10 weeks after rTMS by a psychiatrist (P.A.), also blind to treatment conditions. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (6) and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (7) were used.

We used a 2×8 factorial design (two groups, eight time points) with repeated measurements on the second factor (groups: real rTMS, sham rTMS; times: baseline, six weekly assessments, final 10-week assessment). We predicted that real rTMS would induce significantly greater improvement in OCD than would sham treatment.

Results

All patients completed the study. Only one patient, who received real rTMS, reported mild headache. There were no seizures, neurological complications, or complaints about cognitive difficulties.

Baseline and 10-week scores on the clinical measures are presented in Table 1. At baseline there was no significant difference between the groups receiving real and sham rTMS in scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (U=35.5, p=0.68) or Hamilton depression scale (U=35.0, p=0.65) (Mann-Whitney U test). For the total score on the Yale-Brown scale, two-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed no significant effect for group (F=0.07, df=1, 16, p=0.80) or time (F=1.31, df=7, 112, p=0.25) and no significant group-by-time interaction (F=0.52, df=7, 112, p=0.81). Similar results were obtained for the obsession and compulsion subscales.

For the Hamilton depression scale, ANOVA also showed no significant group effect (F=0.38, df=1, 16, p=0.54), time effect, (F=0.49, df=7, 112, p=0.84), or group-by-time interaction (F=0.31, df=7, 112, p=0.95).

Two patients who received real rTMS, both checkers, were considered responders, defined as having a global reduction in Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale score greater than 40%. This criterion was also met by a patient with sexual/religious obsessions in the group receiving sham treatment. Improvement appeared following the 5th week of treatment in all cases.

Discussion

Among the patients in this study, low-frequency right prefrontal rTMS failed to produce significant improvement in OCD or any difference from sham rTMS.

Differences induced by rTMS in the first hours, which were the main findings of Greenberg et al. (4), were not assessed. Furthermore, our stimulation characteristics differed from those used by Greenberg et al.: we used a circular coil, the frequency was 1 Hz, and the intensity was 110% of motor threshold.

Thirteen of our patients had previously undergone unsuccessful pharmacological treatment for OCD, even combined clomipramine and fluvoxamine therapy, and can therefore be considered to have resistant OCD. This point may have contributed to our negative results.

The selection of the right prefrontal cortex as the target cortical region for stimulation might also explain our findings. Our choice was based on the fact that rTMS of this area was associated in the study of Greenberg et al. (4) with significant reduction of compulsions. Furthermore, rTMS has recently demonstrated remote effects, with left prefrontal stimulation inducing changes in cerebral perfusion in the bilateral anterior cingulate and orbitofrontal cortex (8). The prefrontal cortex may be a starting point to induce remote stimulation of regions consistently involved in OCD, such as the anterior cingulate and orbitofrontal cortex, that cannot be directly stimulated with current rTMS techniques.

Although no significant differences between treatment groups were detected, the patients treated with real rTMS had a somewhat greater reduction in obsessions. Our negative findings may be related to type II error, since a minimum of 27 subjects in each treatment condition would have been necessary to reach an 80% power (alpha=0.05). Although the small group size did not allow us to study OCD subtypes, the fact that both of the responding patients in the group receiving real rTMS were checkers might be clinically relevant.

Further investigation involving larger groups of patients should be performed to clarify whether rTMS could be a useful therapy in OCD and determine the optimal stimulation characteristics for its delivery.

|

Received May 23, 2000; revisions received Oct. 18, 2000, and Jan. 11, 2001; accepted Feb. 1, 2001. From the Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Clinical and Research Unit, Department of Psychiatry, Bellvitge University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain; and the Magnetic Resonance Center of Pedralbes, Barcelona, Spain. Address reprint requests to Dr. Vallejo, Servicio de Psiquiatría, Ciudad Sanitaria y Universitaria de Bellvitge, c/o Feixa Llarga s/n, 08907 Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by grant FIS 00/0226 from the Spanish Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo and by grant 1999FI-00726 to Dr. Alonso from the Generalitat of Catalonia. The authors thank Joan Pau Soto for technical assistance and Gerald Fannon, Ph.D., for revision of the manuscript.

1. George MS, Lisanby SH, Sackeim HA: Transcranial magnetic stimulation: applications in neuropsychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:300-311Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Reid PD, Shajahan PM, Glabus MF, Ebmeier KP: Transcranial magnetic stimulation in depression. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 173:449-452Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Pascual-Leone A, Rubio B, Pallardó F, Català MD: Rapid-rate transcranial magnetic stimulation of left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in drug-resistant depression. Lancet 1996; 348:233-237Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Greenberg BD, George MS, Martin JD, Benjamin J, Schlaepfer TE, Altemus M, Wassermann EM, Post RM, Murphy DL: Effect of prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a preliminary study. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:867-869Link, Google Scholar

5. Klein E, Kreinin I, Chistyakov A, Koren D, Mecz L, Marmur S, Ben-Sachar D, Feinsod M: Therapeutic efficacy of right prefrontal slow repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in major depression: a double-blind controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:315-320Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, Heninger GR, Charney DS: The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, I: development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:1006-1011Google Scholar

7. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56-62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. George MS, Stallings LE, Speer AM, Nahas Z, Spicer KM, Vincent DJ, Bohning DE, Cheng KT, Molloy M, Teneback CC, Risch SC: Prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) changes relative perfusion locally and remotely. Human Psychopharmacology 1999; 14:161-170Crossref, Google Scholar