Dissociation as a Mediator of Psychopathology Among Sexually Abused Children and Adolescents

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study investigated the role of dissociation as a mediator of mental health outcomes in children with a history of sexual abuse. METHOD: The study group consisted of 114 children and adolescents (ages 10–18 years) who were wards of the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services and were living in residential treatment centers. Interviews, provider ratings, and chart reviews were used to assess the relationship of childhood abuse history, dissociative responses, and psychopathology. RESULTS: Sexual abuse history was significantly associated with dissociation, whereas a history of physical abuse was not. Both sexual abuse and dissociation were independently associated with several indicators of mental health disturbance, including risk-taking behavior (suicidality, self-mutilation, and sexual aggression). Severity of sexual abuse was not associated with dissociation or psychopathology. Analysis of covariance indicated that dissociation had an important mediating role between sexual abuse and psychiatric disturbance. These results were replicated across several assessment sources and varied perspectives. CONCLUSIONS: The findings suggest a unique relationship between sexual abuse and dissociation. Dissociation may be a critical mediator of psychiatric symptoms and risk-taking behavior among sexually abused children. The assessment of dissociation among children may be an important aspect of treatment.

Childhood sexual abuse may be related to more deleterious long-term outcomes than physical abuse (1–4). However, no psychiatric profile or course of adjustment unique to the sexual abuse survivor has been identified. Depression, anxiety, and somatic and sexualized responses are frequently documented (5, 6). Risk-taking behaviors (e.g., suicidality, self-mutilation, physical and sexual aggression, substance abuse, and sexual revictimization) have also been noted (7–10). Yet symptoms can wax and wane or shift over the course of development (5, 11), making it difficult to interpret the “real” effect of sexual trauma (12).

While the symptomatic effects of sexual abuse are well-studied (6, 11), the possible mediators of the complex relationship between childhood abuse and psychopathology are currently a focus (11–14). Included is an emphasis on the coping responses of abuse survivors.

A number of studies have assessed the relationship between childhood abuse and dissociation among adult survivors (1–4, 10, 15–17), but this relationship has been less studied among children. The majority of studies suggest that sexual abuse, particularly severe sexual abuse, compared to physical abuse, has the predominant effect on dissociation (2–4, 10, 16). However, other studies have pointed to higher levels of dissociation among subjects with physical abuse or combined sexual and physical abuse (1, 15). Some of this inconsistency may be associated with differences in defining abuse or its severity as well as with difficulties substantiating reports of sexual abuse (16).

A natural, protective response to overwhelming traumatic experiences, dissociation can become an automatic response to stress. This can impair functioning and increase susceptibility to serious psychopathology (17, 18). Putnam (12) has suggested that aggressive, risk-taking behavior often occurs in the context of dissociative experiences, when individuals feel out of control and compelled to do something against their will. A hierarchical model of dissociation proposes that primary dissociation (e.g., forgetfulness, fragmentation, emotional numbing) often co-occurs with several symptom constellations (e.g., mood swings, aggressive behavior, substance abuse). These symptoms are considered secondary or tertiary responses to dissociation in which dissociation serves as a mediator (12). These observable symptoms or risks may not manifest until adolescence or early adulthood (18).

Dissociation and development appear related. Normative dissociation peaks during latency years (age 10) and declines through adolescence and adulthood (17). While some consider pathological dissociation to exist only in adults, adolescence may be a transition period critical to understanding the development of pathological dissociation (18). The early identification of dissociative responses, particularly in relation to risk-taking behavior, may provide important avenues for prevention.

The present study assessed the role of dissociation in the presence of psychiatric symptoms among a group of adolescents and pre-adolescent children with experiences of sexual and physical abuse. It was hypothesized that dissociation would have a mediating role between sexual abuse and mental health outcomes, particularly increasing the likelihood of behaviors that are harmful to self or others.

Method

Study Group and Procedure

One hundred fourteen subjects, ages 10 to 18, were recruited from a group of children who were wards of the State of Illinois Department of Children and Family Services. The group was recruited on the basis of the following five criteria: 1) removal from family and placement into Department of Children and Family Services custody, 2) current placement in residential treatment, 3) age, 4) proximity to Chicago, and 5) agreement to participate. Each child lived in one of five state-supervised residential treatment centers. Two of the residential treatment centers included groups of children treated specifically for sexual aggression. The child’s primary residential treatment caseworker was asked to participate in the study as the caregiver, i.e., an informant who knew the child well. Subjects were not recruited on the basis of any specific abuse history. Children were screened for their ability to participate by staff at each site and were then selected for the study if they agreed to participate. Written informed consent was obtained from both the child and the Public Guardian in Illinois.

The study group included 59 male (52%) and 55 female (48%) subjects. The majority were African American (69%), with 24% Caucasian and 5% Hispanic. The average length of stay in the residential treatment center was 15.2 months (SD=12.2). The mean full-scale IQ was 82 (SD=15), but the range of IQ scores (range=50–125) suggests that the mean score likely was not reflective of the overall study group.

Children were administered the Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale (18) by a clinically trained interviewer and were asked to complete the Youth Self-Report (19). Caregivers were asked to complete the Child Dissociative Checklist (20), the Child Behavior Checklist (21), the Child Acuity of Psychiatric Illness scale (22), and the History of Abuse Form. Trained raters used the Child Severity of Psychiatric Illness scale (22) to review residential charts.

Measures

Dissociation

Two measures of dissociation were used. The Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale (18) is a 30-item self-report measure developed as a screening tool for serious dissociative and posttraumatic disorders. Each item is rated on a scale of 0 (never) to 10 (always) on the basis of adolescents’ self-report of symptoms. The total score for the scale is the average of all item scores. Psychometric data on the Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale indicate excellent reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=0.93; split-half=0.92). A mean score of 4 or above on the Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale signifies pathological dissociation.

The Child Dissociative Checklist (20) is a 20-item observer-report checklist with a 3-point scale (0=not true, 1=sometimes true, 2=frequently true). The Child Dissociative Checklist is a clinical screening instrument that assesses dissociation on the basis of ratings given by caregivers or adults in close contact with the child. A score of 12 or higher on the Child Dissociative Checklist is evidence of pathological dissociation. The Child Dissociative Checklist shows good 1-year test-retest stability (r=0.65) and internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha=0.86) (20). Good convergent and discriminant validity have been indicated (20).

Traumatic experiences

The History of Abuse Form was completed by caregivers. The History of Abuse Form included items abbreviated from another measure (23) and incorporated variables associated with severity of sexual abuse in the literature (5, 6), including type of sexual abuse, age at onset, frequency and duration, relationship and emotional closeness of the perpetrator, and use of force. These data were reported secondhand by the primary caseworker and, therefore, must be interpreted with caution. Asking the youth directly was seen as too intrusive. File review was seen as insufficiently detailed. Information on physical abuse and neglect was also collected.

Mental health outcomes

The Child Behavior Checklist (21) is a 113-item, 0–2 point, observer-report measure. The items comprise several factor-analytically derived problem scales, competence scales, two broadband groupings (internalizing and externalizing problems), and a total problem scale. The Child Behavior Checklist is widely used, with excellent reliability and validity (21). The counterpart to the Child Behavior Checklist, the Youth Self-Report (19), is a child self-report measure with the same scale format and content. The Youth Self-Report exhibits adequate reliability and validity (19).

The Child Acuity of Psychiatric Illness scale (22) is a 21-item, 4-point measure designed to rate acute mental health symptoms, subject to change on the basis of interventions. The Child Acuity of Psychiatric Illness scale includes dimensions of risks, symptoms, functioning, and systems support. The Child Severity of Psychiatric Illness scale (22) is a 25-item, 4-point measure, similar in nature and format to the Child Acuity of Psychiatric Illness scale. It is a chart review measure used to gather recent and historical information on psychiatric functioning.

Results

Eight of the 114 subjects were missing data because of either the child’s unwillingness to complete certain measures or the caregiver’s failure to return the questionnaires (despite multiple requests). This accounts for the variation in number of subjects across measures.

Types of Childhood Abuse Experiences

According to the chart review, 97% of the study group had a history of any type of abuse (sexual, physical, neglect), and 84% of the subjects had an abuse history that was considered moderate to severe. According to the History of Abuse Form, most of the group (92%) experienced some neglect, with 42% experiencing severe neglect or abandonment. Sixty-one percent had a history of sexual abuse, 47% experienced physical abuse, and 39% had both. Children who experienced only sexual abuse without physical abuse made up 22%, while 16% had a history of physical abuse alone, and 49% witnessed the physical abuse of family members.

Among those who reported a history of sexual abuse, the following types of sexual contact were reported: sexual kissing or fondling (11%), touching genitals/digital penetration (16%), oral sex (9%), and genital or anal intercourse (64%). The age at onset of sexual abuse fell into one of four ranges: 0–2 years (4%), 3–6 years (46%), 7–11 years (43%), or 12 years and above (7%). The length of abuse varied: 0–1 year (29%), 1–3 years (36%), 3–5 years (19%), 5 years or more (16%). The frequency of the abuse ranged from either one occasion (8%) or rarely but more than once (26%) to monthly (15%), weekly (38%), and daily (13%). The majority of victims were related to their abuser (who was either an immediate family member [44%] or extended family member [29%]); 4% of the abusers were strangers to the victim, and 23% were unrelated but known. The degree of emotional closeness to the perpetrator was described as follows: no relationship (16%), distant relationship (23%), moderately close (41%), and extremely close (20%). The prototypical picture of sexual abuse was weekly genital or anal intercourse by a family member to whom the child was at least moderately emotionally close, lasting between 1 and 3 years. When multiple types of sexual abuse were reported for a given child, the most severe type was used.

Dissociation

The scores from the Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale (mean=3.2, SD=2.2) and Child Dissociative Checklist (mean=7.6, SD=6.2) were positively correlated with each other (r=0.28, df=100, p<0.01). The magnitude of this correlation suggests that these constructs may not be highly related. It is unclear whether these two measures assess the same phenomenon: children’s report of their own internal experience versus adults’ perception of this experience. Therefore, for the purposes of distinction, we refer to the Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale score as “experienced dissociation” and the Child Dissociative Checklist score as “perceived dissociation.”

There were no significant findings for age and dissociation. There were some gender differences in dissociation: female subjects reported significantly higher levels of experienced dissociation (t=1.95, df=105, p<0.05).

Abuse and Dissociation

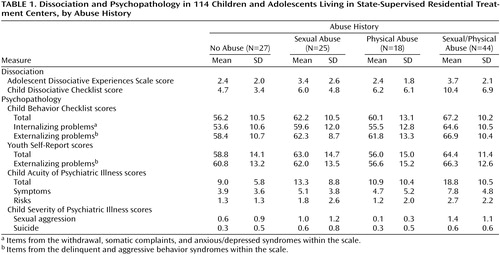

In order to identify the differential effects of sexual and physical abuse experiences, a two-by-two analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. Main effects were tested for sexual abuse (yes versus no) and physical abuse (yes versus no). Statistical interactions between sexual and physical abuse were also tested to determine whether the co-occurrence of sexual abuse and physical abuse had differential effects greater than the occurrence of either sexual abuse or physical abuse alone. Mean scores on the dissociation measures for the 114 subjects grouped by abuse history (no abuse, sexual abuse only, physical abuse only, both sexual and physical abuse) are presented in Table 1.

For experienced dissociation (i.e., scores on the Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale), there was only a main effect for sexual abuse: children with sexual abuse histories reported significantly higher levels of dissociation (F=6.88, df=1, 103, p<0.01). There was no effect for physical abuse and no interaction effect. For perceived dissociation (i.e., scores on the Child Dissociative Checklist), both main effects were significant: higher levels of perceived dissociation were seen in children with a history of either physical abuse (F=6.40, df=1, 103, p<0.05) or sexual abuse (F=5.54, df=1, 103, p<0.05). There was no interaction effect. There was also no relationship between circumstances or severity of sexual abuse and dissociation.

Abuse and Psychiatric Status

Again, two-by-two ANOVAs were conducted across the measures of symptomatic functioning, with physical abuse and sexual abuse as main effects. Mean scores on the symptom measures for the 114 subjects grouped by abuse history are presented in Table 1.

Most of the significant main effects for the Child Behavior Checklist were related to sexual abuse. Higher total scores were seen in children with histories of physical abuse (F=4.13, df=1, 105, p<0.05) and sexual abuse (F=9.0, df=1, 105, p<0.01). Children with a history of sexual abuse also had higher scores for internalizing problems (F=10.8, df=1, 105, p<0.01) and externalizing problems (F=4.32, df=1, 105, p<0.05), whereas there was no main effect for physical abuse and no interaction effect for either subscale. On the Youth Self-Report, there were only main effects for sexual abuse: children with a history of sexual abuse had higher total scores (F=4.81, df=1, 106, p<0.05) and externalizing problem scores (F=4.11, df=1, 106, p<0.05).

On the Child Acuity of Psychiatric Illness scale, there was a main effect for sexual abuse: children with a history of sexual abuse had higher total scores (F=9.26, df=1, 91, p<0.01), indicating more acute problems, and higher symptom (F=5.48, df=1, 100, p<0.05) and risk (F=5.18, df=1, 104, p<0.05) scores. There were no main effects for physical abuse or interaction effects for these scores.

On the Child Severity of Psychiatric Illness scale, there was a main effect for sexual abuse and an interaction effect for sexual aggression scores: higher scores were seen in children with a history of sexual abuse (F=17.51, df=1, 105, p<0.001) and both sexual and physical abuse (F=4.64, df=1, 105, p<0.05). There was no main effect for physical abuse. There was also a main effect for sexual abuse on suicide scores (F=6.16, df=1, 107, p<0.05) but no effect for physical abuse and no interaction effect. No associations between sexual abuse severity and any measure of psychiatric status were seen.

Finally, a multivariate ANOVA was run across all dependent variables to test the overall significance of physical and sexual abuse. There was a significant multivariate main effect for sexual abuse (Wilks’s lambda=3.82, df=13.0, p<0.0001) but not for physical abuse or the sexual/physical abuse interaction.

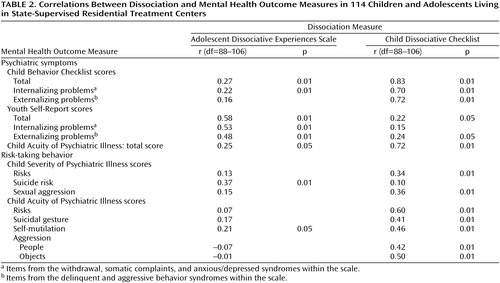

Dissociation and Psychiatric Status

Several significant relationships were found between the measures of dissociation and mental health outcome (Table 2). There were significant inverse correlations between perceived dissociation (Child Dissociative Checklist score) and several of the competence scales from the Child Behavior Checklist, such as activities (r=–0.30, df=106, p<0.01), social functioning (r=–0.38, df=106, p<0.01), and school performance (r=–0.29, df=106, p<0.01). The activities score was also inversely correlated with experienced dissociation (Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale score) (r=–0.25, df=106, p<0.05).

Dissociation as a Mediator

Analyses of covariance were performed to determine whether the relationship between sexual abuse and mental health outcomes was mediated by dissociation. Sexual and physical abuse were used as factors, with experienced and perceived dissociation as covariates.

For the Child Behavior Checklist total score, perceived dissociation was significant as a covariate (F=153.4, df=1, 95, p<0.001). Previously significant main effects for sexual and physical abuse were no longer significant. Perceived dissociation was a significant covariate for the internalizing (F=66.7, df=1, 95, p<0.001) and externalizing (F=80.2, df=1, 95, p<0.001) problem scores. The main effect for sexual abuse on these scores was eliminated after we controlled for dissociation.

Experienced dissociation was a significant covariate for both total score (F=40.9, df=1, 93, p<0.001) and the externalizing problems score (F=18.8, df=1, 93, p<0.001) from the Youth Self-Report. Previously significant main effects for sexual abuse on both scores disappeared after we controlled for dissociation.

For scores on the Child Acuity of Psychiatric Illness scale, perceived dissociation was a significant covariate (total: F=86.6, df=1, 83, p<0.001; risks: F=49.4, df=1, 95, p<0.001; symptoms: F=74.6, df=1, 92, p<0.001). The previously significant main effect for sexual abuse on all three indices disappeared.

For scores on the Child Severity of Psychiatric Illness scale, experienced dissociation was a significant covariate for suicide risk (F=7.36, df=1, 94, p<0.01). The previously significant main effect for sexual abuse was again not present. However, a slightly different pattern emerged for sexual aggression: while perceived dissociation was again a significant covariate (F=5.0, df=1, 93, p<0.05), a significant main effect remained for sexual abuse (F=8.64, df=1, 93, p<0.01) and the physical and sexual abuse interaction (F=4.43, df=1, 93, p<0.05).

Discussion

The primary finding of this study is that dissociation appears to have a mediating role between sexual abuse and a variety of mental health outcomes. Higher levels of dissociation were found among sexually abused children than among physically abused children. Dissociation was associated with more symptoms, more frequent risk-taking behaviors, and less competent functioning. Consistent with other research, sexually abused children exhibited more symptoms and acute disturbance, including suicidality, sexual aggression, and self-mutilation (6–9). Associations between severity of sexual abuse, dissociation, and outcomes were not found, likely because of the consistently severe abuse histories within this study group. Overall, these findings suggest a unique relationship between sexual abuse and dissociation (1, 9) and the potential importance of dissociation as a mediator of symptoms, particularly destructive and harmful behaviors, among sexually abused children (14). These findings are compelling and may have clinical implications for work with traumatized children.

This study has a number of strengths, including its multimethod design, mixed gender sample, and replication of findings across several measures and perspectives. There are also limitations and questions to consider. One important issue concerns the measures of dissociation: the Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale, referred to as “experienced dissociation,” and the Child Dissociative Checklist, a “perceived dissociation” measure. While associated with each other, these variables were not highly correlated, perhaps reflecting separate constructs. The dissociation measures were primarily associated with outcomes of the same informant (e.g., child-reported dissociation to child-reported symptoms), yet some significant cross-informant relationships still existed. Thus, the findings cannot be attributed solely to method variance.

It is possible that children, particularly adolescents, are better able to describe their internal experience; adult observations of dissociation may reflect external behaviors related to dissociation. This could represent a central difficulty in measuring dissociation in children. Pathological dissociation may be clinically inferred by the degree of problematic (e.g., destructive or harmful) behavior that is present. Alternately, if a child’s behavior is sufficiently disruptive and dissociation is not assessed in a particular setting, it may be overlooked. In fact, the Child Dissociative Checklist, the adult-report measure, includes an item on sexual behavior in its rating of dissociation. This could have presented a confound for this study as dissociation was hypothesized to mediate risk behaviors.

In this study, dissociation was measured on a continuum as it relates to abuse history and mental health outcome. While the dissociation scores for this group were similar to those of other samples of abused children, the average scores were not within the pathological or diagnostic range for dissociation (18, 20).

Evidence for a relationship among abuse history, dissociation, and psychopathology was quite compelling, but the data only suggest that these variables are associated at the present time. Causal effects and directional relationships cannot be inferred given the cross-sectional design of this study.

This was an extreme sample of the child psychiatric population. All of the subjects were in state protective custody and receiving long-term psychiatric services. Therefore, direct responses to abuse were not assessed, and symptoms may have shifted over time as a result of other experiences. With a significant subset of children exhibiting some history of sexual aggression, the generalizability of these findings to other populations may be limited.

Conclusions

Dissociation has been considered a mediator of psychopathology and risk-taking behavior in previous studies of childhood sexual abuse (2, 3, 12, 14) and adult sexual trauma (24). This study supports these findings and may have implications for treatment. Assessing dissociation may be an important aspect of clinical care among traumatized children. However, fully understanding these relationships requires further empirical studies with multiple and varied methods and measurement among individuals at different developmental stages. It would be useful to assess children and their dissociative responses closer to the time of abuse and across development to understand how dissociation relates to psychiatric outcomes over time. It is also important to consider how pathological levels of dissociation relate to symptoms and risk. Longitudinal studies are critical for assessing how dissociation is adaptive in the short term and when and how it becomes maladaptive. Future research is needed in these areas to better understand these complex phenomena, forestall inappropriate diagnosis and treatment, and prevent further trauma in the lives of abused children.

|

|

Received July 12, 1999; revisions received March 2 and Nov. 13, 2000; accepted Jan. 9, 2001. From the Wellesley Centers for Women, Wellesley College; and the Mental Health Services and Policy Program, Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago. Address reprint requests to Dr. Kisiel, The Wellesley Centers for Women, Wellesley College, 756 Washington St., Waban House, Wellesley, MA 02481.Supported in part by a grant from the Philanthropic Educational Organization. The authors thank Drs. Richard Carroll, Geri Donenberg, and Karen Gouze for their help in the conceptualization and design of this study and Dr. Drew Westen for his editorial comments on an earlier draft of this article.

1. Chu JA, Dill DL: Dissociative symptoms in relation to childhood physical and sexual abuse. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:887-892Link, Google Scholar

2. Waldinger RJ, Swett C, Frank A, Miller K: Levels of dissociation and histories of reported abuse among women outpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis 1994; 182:625-630Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Zlotnick C, Begin A, Shea MT, Pearlstein T, Simpson E, Costello E: The relationship between characteristics of sexual abuse and dissociative experiences. Compr Psychiatry 1994; 35:465-470Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Chu JA, Frey LM, Ganzel BL, Matthews JA: Memories of childhood abuse: dissociation, amnesia, and corroboration. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:749-755Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Beitchman JH, Zucker KJ, Hood JE, DaCosta GA, Akman D: A review of the short-term effects of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl 1991; 15:537-556Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Kendall-Tackett KA, Williams LM, Finkelhor D: Impact of sexual abuse on children: a review and synthesis of recent empirical studies. Psychol Bull 1993; 113:164-180Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kaplan ML, Asnis GM, Lipschitz DS, Chorney P: Suicidal behavior and abuse in psychiatric outpatients. Compr Psychiatry 1995; 36:229-235Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Gladstone G, Parker G, Wilhelm K, Mitchell P, Austin M-P: Characteristics of depressed patients who report childhood sexual abuse. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:431-437Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Singer MI, Petchers MK, Hussey D: The relationship between sexual abuse and substance abuse among psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents. Child Abuse Negl 1989; 13:319-325Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Draijer N, Langeland W: Childhood trauma and perceived parental dysfunction in the etiology of dissociative symptoms in psychiatric inpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:379-385Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Pynoos RS, Steinberg AM, Wraith R: A developmental model of childhood traumatic stress, in Developmental Psychopathology, vol 2: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation. Edited by Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ. New York, Wiley & Sons, 1995, pp 72-95Google Scholar

12. Putnam FW: Dissociation in Children and Adolescents: A Developmental Perspective. New York, Guilford Press, 1997Google Scholar

13. Finkelhor D, Browne A: The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: a conceptualization. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1985; 55:530-541Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Long PJ, Jackson JL: Childhood coping strategies and the adult adjustment of female sexual abuse victims. J Child Sex Abuse 1993; 2:23-39Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Sanders B, Giolas MH: Dissociation and childhood trauma in psychologically disturbed adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:50-54Link, Google Scholar

16. McElroy LP: Early indicators of pathological dissociation in sexually abused children. Child Abuse Negl 1992; 16:833-846Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Putnam FW: Dissociative disorders in children: behavioral profiles and problems. Child Abuse Negl 1993; 17:39-45Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Armstrong J, Putnam FW, Carlson EB, Libero DZ, Smith SR: Development and validation of a measure of adolescent dissociation: the Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale (A-DES). J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:491-497Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Achenbach TM: Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. Burlington, University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, 1991Google Scholar

20. Putnam FW, Helmers K, Horowitz LA, Trickett PK: Development, reliability, and validity of a child dissociation scale. Child Abuse Negl 1993; 17:731-741Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C: Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, 1983Google Scholar

22. Lyons JS: The Severity and Acuity of Psychiatric Illness, Child and Adolescent Version. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp (Harcourt), 1998Google Scholar

23. Wolfe VV, Gentile C, Bourdeau P: History of Victimization Questionnaire. London, Ont., Canada, Children’s Hospital of Western Ont., 1986Google Scholar

24. Feeny NC, Zoellner LA, Foa EB: Anger, dissociation, and posttraumatic stress disorder among female assault victims. J Trauma Stress 2000; 13:89-100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar