Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Bulimia Nervosa

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The effects of dialectical behavior therapy adapted for the treatment of binge/purge behaviors were examined. METHOD: Thirty-one women (averaging at least one binge/purge episode per week) were randomly assigned to 20 weeks of dialectical behavior therapy or 20 weeks of a waiting-list comparison condition. The manual-based dialectical behavior therapy focused on training in emotion regulation skills. RESULTS: An intent-to-treat analysis showed highly significant decreases in binge/purge behavior with dialectical behavior therapy compared to the waiting-list condition. No significant group differences were found on any of the secondary measures. CONCLUSIONS: The use of dialectical behavior therapy adapted for treatment of bulimia nervosa was associated with a promising decrease in binge/purge behaviors.

Cognitive behavior therapy is generally considered the treatment of choice for bulimia nervosa (1). Yet, after completing cognitive behavior therapy, approximately 50% of patients continue to binge eat and purge (2). Considerable evidence, including experimental studies, links negative emotions with bulimic behaviors (3–5). Initial support has been reported for a treatment specifically developed to target these difficulties with affect regulation in bulimia nervosa (6) and binge eating disorder (7).

Dialectical behavior therapy, developed by Linehan to treat borderline personality disorder (8, 9), is currently the most comprehensive and empirically validated affect regulation treatment. In light of preliminary evidence of positive findings from the application of dialectical behavior therapy to bulimia nervosa (10–12), we conducted a randomized controlled study comparing the outcome of 20 weeks of dialectical behavior therapy with 20 weeks of a wait-list condition in patients with binge/purge behaviors.

Method

Thirty-one women (age 18–65 years) with, on average, at least one binge/purge episode per week over the previous 3 months were recruited through newspaper advertisements and clinic referrals. All gave written consent before study participation. The rationale for using modified DSM-IV criteria for bulimia nervosa (one binge/purge episode per week rather than the two episodes required in the full DSM-IV criteria ) was to broaden the study’s applicability. Patients seen in general clinic settings commonly complain of considerable bulimic symptoms, but, because the symptoms do not meet the full criteria, such patients are often excluded from research.

Twenty-five participants (80.6%) met the full DSM-IV criteria for bulimia nervosa, and six met the modified DSM-IV criteria. Exclusionary criteria included 1) body mass index <17.5, 2) psychosis or severe depression with suicidal ideation, 3) active drug/alcohol abuse, and 4) concurrent participation in psychotherapy or concurrent use of antidepressants or mood stabilizers. Participants in the 20-week waiting-list condition were reassessed by phone regarding any therapeutic involvement during the 20-week period. Only one subject in the waiting-list group indicated that she was unable to comply with the request to avoid concomitant therapy. In the intent-to-treat analysis, this subject’s baseline scores were carried forward.

Enrolled participants were randomly assigned to the treatment condition or the waiting-list condition in blocks of eight to ensure balanced numbers of participants in each condition. For random assignment of each block of participants, eight sealed envelopes (four that contained assignment to the treatment condition and four to the waiting-list condition) were shuffled, numbered 1 through 8, and given to the participants on entry into the study.

The participants who were assigned to the waiting-list condition were offered dialectical behavior therapy after they completed the assessments at the end of the 20-week waiting-list condition. Baseline and posttreatment measures included the Eating Disorder Examination (13), the Negative Mood Regulation Scale (14), the Beck Depression Inventory, the Emotional Eating Scale (15), the Multidimensional Personality Scale (16), the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (17), and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (18).

The interviewers who used the Eating Disorder Examination received training by Dr. Christopher Fairburn, who developed this measure. A recent study demonstrated interrater agreement above 0.90 for all Eating Disorder Examination subscales and behavior items and test-retest agreement above 0.70, except for the item on subjective bulimic episodes (0.40) (19). In the study reported here, all interviews with the Eating Disorder Examination were audiotaped. The consistency of the examiners’ interviewing techniques was checked by an independent rater who reviewed randomly selected audiotapes.

Treatment involved 20 sessions of weekly 50-minute individual psychotherapy specifically aimed at teaching emotional regulation skills to reduce rates of binge eating and purging. The treatment manual was adapted for the treatment of bulimia nervosa from Linehan’s Skills Training Manual for Treating Borderline Personality Disorder (9). Treatment was delivered by one female psychiatrist (D.L.S.).

Briefly, the dialectical behavior therapy model of bulimia nervosa views emotional dysregulation as the core problem in bulimia nervosa, with binge eating and purging understood as attempts to influence, change, or control painful emotional states. Patients are taught a repertoire of skills to replace dysfunctional behaviors. (See Wiser and Telch [20] for a detailed description of the treatment.)

Results

The participants’ mean age was 34 years (SD=11, range=18–54). Most were white (N=27, 87.1%), were either employed (N=16, 51.6%) or full-time students (N=7, 22.6%), were either single (N=12, 38.7%) or married (N=12, 38.7%), and had at least some college education (N=24, 77.4%). Their mean age when beginning bulimic behaviors was 22.3 years (SD=7.0, range=14.5–41.5), and these behaviors had continued for 12.2 years (SD=8.6, range=0.5–29.5). Their mean body mass index was 23.7 (SD=5.6, range=17.8–42.1). At baseline, they had had a median of 25 objective binge episodes and 32 purge episodes over the past 28 days. (An objective binge episode consists of a large amount of food eaten with loss of control, as defined by the Eating Disorder Examination [13]). No significant differences were found between the participants who were randomly assigned to dialectical behavior therapy (N=14) or to the waiting-list condition (N=15) on any of the baseline variables except the pretreatment Negative Mood Regulation Scale score (t=2.46, df=29, p=0.02).

Three patients did not complete the study; one dropped out from the waiting-list group and two were withdrawn from treatment (owing to pregnancy, for one patient, and to new-onset psychosis, for the other patient).

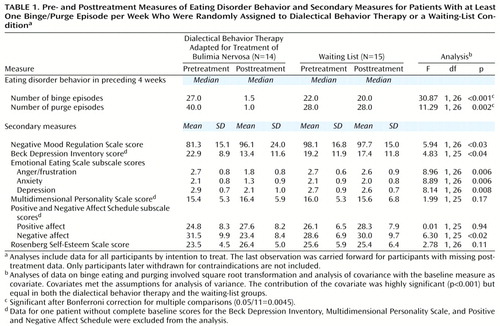

The results on the primary and secondary outcome measures are presented in Table 1. Calculating effect sizes according to Cohen’s method (21), we found significant treatment effects in the intent-to-treat analysis for the frequency of both binge eating (effect size=1.15) and purging behaviors (effect size=0.61). Although there are no absolute standards for interpreting effect sizes, an effect size of 0.2 is generally considered small, 0.5 is considered moderate, and 0.8 is considered large. For the secondary measures, effect sizes greater than 0.5 were found for the three subscales of the Emotional Eating Scale (anger/frustration, effect size=0.89; anxiety, effect size=0.78; and depression, effect size=0.56) and for the negative affect subscale of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (effect size=0.70).

At 20 weeks, four participants in the dialectical behavior therapy group (28.6%) were abstinent from binge eating/purging behaviors, compared with no participants in the waiting-list group (p<0.05, Fisher’s exact test). Five patients in the dialectical behavior therapy group (35.7%) had mild symptoms, reducing their number of objective binge eating episodes by 88% and of purging episodes by 89%. Five dialectical behavior therapy participants (35.7%) remained symptomatic and met DSM-IV criteria for bulimia nervosa. Two waiting-list participants (13.3%) had mild symptoms (and no reduction in the number of binge or purge episodes), and 12 (80.0%) continued to be symptomatic.

No significant differences between groups were found for the secondary measures, after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (0.05/11=0.0045).

Discussion

Although the association between negative affect and binge eating/purging is well established, this is the first randomized controlled study to support a role for dialectical behavior therapy in emotion regulation treatment for individuals with bulimia nervosa. The results show that participants’ rates of binge eating and purging significantly decrease after treatment aimed at teaching adaptive emotion regulation skills.

None of the secondary measures listed in Table 1 revealed significant differences between groups. The small sample size, one of the limitations of this study, may have reduced the power to detect differences between the groups. Furthermore, without comparisons that involve other conditions besides the waiting-list condition, we cannot confidently conclude that dialectical behavior therapy specifically had an effect on bulimic symptoms beyond the nonspecific effects of psychotherapy.

Nevertheless, as a preliminary report, the findings of overall improvements in binge eating/purge behaviors are suggestive. Of particular note is the low treatment dropout rate (0%). Cognitive behavior therapy, in a recent multicenter trial (22), had a 28% dropout rate and an intent-to-treat abstinence rate of 27%—a rate similar to that found in this study (28.6%). In addition, the findings of larger effect sizes for the three Emotional Eating Scale subscales and the negative affect subscale of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule suggest that dialectical behavior therapy works more by decreasing participants’ vulnerability to negative emotions associated with the urge to binge and purge than by directly targeting areas such as self-esteem and overall impulsivity.

Further studies with a greater number of participants and more than one comparison group appear to be warranted. In addition, it would be of particular interest to determine the characteristics of those participants with binge/purge behaviors who respond best to dialectical behavior therapy.

|

Received July 6, 2000; revision received Oct. 18, 2000; accepted Nov. 16, 2000. From the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine. Address reprint requests to Dr. Safer, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, 401 Quarry Rd., Stanford, CA 94305-5722; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by NIMH postdoctoral fellowship 5-T32NG-19938 (Dr. Safer) and NIMH grants MH-50371 and MH-19938. The authors thank Teresa J. Lively, B.A., and Mathilde Weems, M.D., for their assistance with this study.

1. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Eating Disorders (Revision). Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157(Jan suppl)Google Scholar

2. Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa, in Handbook of Treatment for Eating Disorders. Edited by Garner DM, Garfinkel PE. New York, Guilford Press, 1997, pp 67–93Google Scholar

3. Polivy J, Herman CP: Etiology of binge eating: psychological mechanisms, in Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. Edited by Fairburn CG, Wilson GT. New York, Guilford Press, 1993, pp 173–205Google Scholar

4. Agras WS, Telch CF: The effects of caloric deprivation and negative affect on binge eating in obese binge-eating-disordered women. Behavior Therapy 1998; 29:491–503Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Telch CF, Agras WS: Do emotional states influence binge eating in the obese? Int J Eat Disord 1996; 20:271–279Google Scholar

6. Esplen MJ, Garfinkel PE, Olmsted M, Gallop RM, Kennedy S: A randomized controlled trial of guided imagery in bulimia nervosa. Psychol Med 1998; 28:1347–1357Google Scholar

7. Telch CF, Agras WS, Linehan MM: Group dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating disorder: a preliminary uncontrolled trial. Behavior Therapy 2000; 31:569–582Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Linehan MM: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford Press, 1993Google Scholar

9. Linehan MM: Skills Training Manual for Treating Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford Press, 1993Google Scholar

10. Safer DL, Telch CF, Agras WS: Dialectical behavior therapy adapted for bulimia nervosa: a case report. Int J Eating Disord (in press)Google Scholar

11. Marcus MD, McCabe EB, Levine MD: DBT in the treatment of eating disorders, in 4th London International Conference on Eating Disorders. London, Mark Allen International Communications, 1999, p 29Google Scholar

12. Garward N, McGrain L, Palmer B, Birchall H: The application of dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) to the treatment of eating disorders and co-morbid borderline personality disorder, in Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Eating Disorders. McLean, Va, Academy for Eating Disorders, 2000, p 9Google Scholar

13. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z: The Eating Disorder Examination, 12th ed, in Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment and Treatment. Edited by Fairburn CG, Wilson GT. New York, Guilford Press, 1993, pp 317–360Google Scholar

14. Catanzaro SJ, Mearns J: Measuring generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation: initial scale development and implications. J Pers Assess 1990; 54:546–563Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Arnow B, Kenardy J, Agras WS: The Emotional Eating Scale: the development of a measure to assess coping with negative affect by eating. Int J Eat Disord 1995; 18:79–90Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Tellegen A, Waller N: Exploring personality through test construction: development of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire, in Personality Measures: Development and Evaluation, vol 1. Edited by Briggs SR, Cheek JM. Greenwich, Conn, JAI, 1994, pp 172–208Google Scholar

17. Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A: Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988; 54:1063–1070Google Scholar

18. Rosenberg M: Society and the Adolescent Self Image. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1965Google Scholar

19. Rizvi SL, Peterson CB, Crow SJ, Agras WS: Test-retest reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination. Int J Eat Disord 2000; 28:311–316Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Wiser S, Telch CF: Dialectical behavior therapy for binge-eating disorder. J Clin Psychol 1999; 55:755–768Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988Google Scholar

22. Agras WS, Fairburn CG, Walsh T, Wilson GT, Kraemer HC: A multicenter comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:459–466Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar