Suppression of Cellular Immunity in Men With a Past History of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Abstract

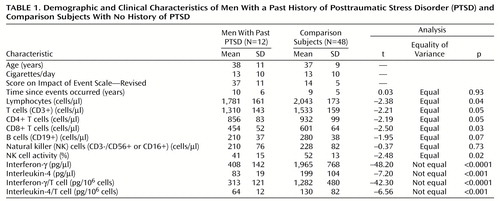

OBJECTIVE: High rates of medical morbidity have been reported in subjects with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The authors examined immune function in subjects in remission from past PTSD. METHOD: The initial study group was composed of 1,550 Japanese male workers. Japanese versions of the Events Check List, the Impact of Event Scale—Revised, and the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV were used to identify subjects who had a past history of PTSD. Twelve of the workers were identified as having such a history. These men were matched in age and smoking habits, which affect immunity, to 48 comparison subjects who had similar stressful life experiences but no current or past history of PTSD. Natural killer (NK) cell activity, lymphocyte subset counts, and production of interferon γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin-4 (IL-4) were measured in the 60 men by means of phytohemagglutinin stimulation. RESULTS: The number of lymphocytes, number of T cells, NK cell activity, and total amounts of IFN-γ and IL-4 were significantly lower in the 12 men with a past history of PTSD. CONCLUSIONS: PTSD leaves a long-lasting immunosuppression and has long-term implications for health.

It has been suggested that posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has not only long-lasting psychological but also long-lasting biological morbid effects. A 50-year prospective study demonstrated that combat exposure predicted early death and chronic illnesses by the age of 65 (1). A link between exposure to severe stress and later physical diseases has also been mentioned (2), but there is no biological evidence for this link as yet. A series of studies revealed several biological dysfunctions in patients with current PTSD, such as low levels of 24-hour urinary cortisol excretion (3), high natural killer (NK) cell activity (4) and high CD4 and CD8 T cell numbers (5, 6). To our knowledge, however, no study has focused on chronic biological effects among subjects who had PTSD in the past but who are now in remission. This study investigates the association between a past history of PTSD and any present immune dysfunction; our goal was to detect any long-lasting morbid effects of this disorder.

Method

We administered the Japanese versions of the Events Check List (7) and the Impact of Event Scale—Revised (8) to 1,550 male workers randomly recruited from a medium-sized Japanese industrial company. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Past exposure to traumatic events was examined through the Events Check List, which comprises 15 categories such as natural disasters, violence, bullying, etc. Men who had been exposed to such events were screened for traumatic symptoms by using the Japanese version of the Impact of Event Scale—Revised (8), which has demonstrated 100% sensitivity for subjects with current and lifetime diagnosis of PTSD when a cutoff point of 24 was applied. Participants with a score greater than 24 were interviewed with the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (9) to diagnose current and past PTSD and other axis I disorders.

Exclusion criteria included a previous history of any axis I disorder other than PTSD, use of any psychotropic medication within 2 months before this study, and any physical illness that needed treatment.

We recruited as many comparison subjects as possible from participants who had been exposed to trauma but whose Impact of Event Scale—Revised scores were below 25. The comparison subjects were matched for age and smoking because these factors affect immunity.

Blood samples were collected in heparinized tubes (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, N.J.) at 10:00 a.m. and stored at room temperature for no longer than 4 hours before the assays. To determine WBC subset counts, the total numbers of WBC and leukocyte differential counts were determined with a Coulter counter (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, Calif.). Lymphocyte subsets were determined by flow cytometry analysis (EPICS XL, Beckman Coulter, Inc.) according to standard methods. Enumeration by flow cytometry included the following cells: T cells (CD3/fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]), B cells (CD19/phycoerythrin [PE]), two types of T cell subsets (CD4/FITC, CD8/PE), and NK cells (CD3/phycoerythrin-Texas red [ECD], CD16/FITC, and CD56/PE). All antibodies were purchased from Beckman Coulter, Inc.

For determination of interferon γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin-4 (IL-4), a whole blood assay was applied (10). Aliquots of 50 μl of blood were resuspended under laminar airflow in 400 μl of RPMI 1640 medium (containing 2 mM glutamine and 100 μg/ml kanamycin). For stimulation of cytokines, 2.5 μg phytohemagglutinin (Sigma-Aldrich Japan, Tokyo) was added and dissolved in 50 μl of a medium containing 50% RPMI and 50% sterile water (final concentration, 5 μg/ml). The samples were incubated for 48 hours at 37°C with 5% carbon dioxide in humidified air. The supernatants were harvested and stored at –80°C until assay. All cytokine levels were measured by ELISA kits (Biosource International, Camarillo, Calif.). Each sample was tested in duplicate in the same assay and thawed only once (10). The NK cell activity assay was performed with K562 as target cells (E:T=20:1) and 51chromium release as the lysis indicator.

We used Student’s t tests with Levine’s test to compare the results between the subjects with and without past PTSD; p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Of 1,550 male workers, 1,009 completed the Event Check List and 447 reported previous exposure to a life-threatening event. Fifty-seven men had Impact of Event Scale—Revised scores higher than 24, and 52 agreed to participate in the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (interrater kappa for the first 12 participants was 0.92). Three men had current PTSD and 12 had past PTSD but were in remission. The events that caused the past PTSD were various: bullying, traffic accidents, witnessing a cruel death, violence, fire, death in the family, and flood.

We found 48 comparison subjects for the 12 men with past PTSD (case-comparison ratio=1:4). As shown in Table 1, there was no significant difference in number of years passed since the exposure to trauma between the men with and without past PTSD. The number of lymphocytes, number of T cells, number of T cell subsets, NK cell activity, and total amounts of IFN-γ and IL-4 as well as amounts produced by T cell were significantly lower in the PTSD group.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report on long-lasting immunosuppression associated with past PTSD, which can help explain its elevated morbidity. Strikingly, although the reported traumatic events were less threatening than holocaust or crime, the subjects with past PTSD suffered from global immunosuppression. Current PTSD has been claimed to activate cellular immunity, presumably because of the “fight or flight” up-regulatory immune response by “flashbacks” or episodes of reliving the stressor (4, 5). This supports our finding that the three men with current PTSD, who were not included in the group of subjects with past PTSD, had significantly higher NK cell activity (mean=52.7%, SD=10.2%) than the comparison subjects (mean=48.2%, SD=8.2%). Further investigations are required to elucidate the mechanisms of immunological up-regulation of current PTSD and down-regulation of past PTSD. The influence of ongoing distress among past PTSD subjects should also be examined. In conclusion, PTSD has long-term implications for immunity and health.

|

Received March 31, 2000; revision received July 18, 2000; accepted Oct. 19, 2000. From the Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and the Department of Adult Mental Health, National Institute of Mental Health, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry; and the Department of Social Psychiatry, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Psychiatry. Address reprint requests to Dr. Kawamura, Department of Psychosomatic Medicine, National Institute of Mental Health, NCNP, 1-7-3 Kounodai Ichikawa Chiba 272-0827, Japan. Supported in part by grant 10B-4 for posttraumatic stress disorder research from the Ministry of Health and Welfare.

1. Lee KA, Vaillant GE, Torrey WC, Elder GH: A 50-year prospective study of the psychological sequelae of World War II combat. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:516–522Link, Google Scholar

2. Boscarino JA: Diseases among men 20 years after exposure to severe stress: implications for clinical research and medical care. Psychosom Med 1997; 59:605–614Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Yehuda R, Kahana B, Binder-Brynes K, Southwick SM, Mason JW, Giller EL: Low urinary cortisol excretion in Holocaust survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:982–986Link, Google Scholar

4. Laudenslager ML, Aasal R, Adler L, Berger CL, Montgomery PT, Sandberg E, Wahlberg LJ, Wilkins RT, Zweig L, Reite ML: Elevated cytotoxicity in combat veterans with long-term post-traumatic stress disorder: preliminary observations. Brain Behav Immun 1998; 12:74–79Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Boscarino JA, Chang J: Higher abnormal leukocyte and lymphocyte counts 20 years after exposure to severe stress: research and clinical implications. Psychosom Med 1999; 61:378–386Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Wilson SN, van der Kolk B, Burbridge J, Fisler R, Kradin R: Phenotype of blood lymphocytes in PTSD suggests chronic immune activation. Psychosomatics 1999; 40:222–225Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Asukai N: Validation of Japanese version of the Impact of Event Scale—Revised, in Annual Report of the Research on Nervous and Mental Disorders. Tokyo, Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2000Google Scholar

8. Weiss D: Psychometric review of the Impact of Event Scale—Revised, in Measurement of Stress, Trauma, and Adaptation. Edited by Stamm BH. Lutherville, Md, Sidran Press, 1996, pp 186–188Google Scholar

9. Robins LN, Cottler L, Bucholz K, Compton W: Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. St Louis, Washington University, 1995Google Scholar

10. Born J, Lange T, Hansen K, Molle M, Fehm HL: Effects of sleep and circadian rhythm on human circulating immune cells. J Immunol 1997; 158:4454–4464Google Scholar