Psychiatrists Disciplined by a State Medical Board

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study determined the risk of discipline by a medical board for psychiatrists relative to other physicians and assessed the contributions to such risk. METHOD: Physicians disciplined by the California Medical Board in a 30-month period were compared with matched groups of nondisciplined physicians. RESULTS: Among 584 disciplined physicians, there were 75 (12.8%) psychiatrists, nearly twice the number of psychiatrists among nondisciplined physicians. Female psychiatrists were underrepresented in the disciplined group. Psychiatrists were significantly more likely than nonpsychiatrist physicians to be disciplined for sexual relationships with patients and about as likely to be charged with negligence or incompetence. The disciplined and nondisciplined psychiatrists did not differ significantly from a group of 75 nondisciplined psychiatrists on years since medical school graduation, international medical graduate status, or board certification. The disciplined group included significantly more psychiatrists who claimed child psychiatry as their first or second specialty and significantly fewer psychoanalysts. CONCLUSIONS: Organized psychiatry has an obligation to address sexual contact with patients and other causes for medical board discipline. This obligation may be addressable through enhanced residency training, recertification exams, and other means of education.

To date, there has been no comprehensive study of psychiatrists who have been disciplined by a state medical board or other jurisdiction. Although Morrison and Wickersham (1) reported that psychiatrists were somewhat overrepresented in a group of 375 physicians disciplined by the California Medical Board, their data did not permit definitive conclusions about any physician specialty. A number of articles have addressed specific types of physician misconduct, but the conclusions of these studies have sometimes been conflicting.

Several studies of malpractice rates and insurance losses (2–4) have found psychiatrists less likely than other physician specialists to incur malpractice claims or to lose malpractice insurance. Psychiatrists are about as likely as other physicians to prescribe drugs inappropriately (5, 6) and have been overrepresented among physicians investigated for inappropriate personal relationships with patients (7–9). Finally, although several studies of physically or mentally impaired physicians (10–12) have reported more psychiatrists than expected, Talbott et al. (13) did not find psychiatrists to be overrepresented in a study of 1,000 impaired Georgia physicians.

In this study we examine the risk of psychiatrists’ being disciplined in a consecutive series of physicians disciplined by the California Medical Board during a 30-month period. On the basis of work previously cited, we predicted that psychiatrists would be 1) overrepresented in the general group of physicians and 2) more likely than other physicians to be disciplined for sexual misconduct.

Method

The Medical Board of California disciplines about 250 physicians annually. The report of each such action, published in the quarterly bulletin titled Action Report(14), includes the physician’s name, city and state of current record, description of cause of action, and nature and date of action. For each physician so identified, additional data were obtained from the American Medical Association’s (AMA’s) Directory of Physicians(15), which lists more than 723,000 physicians licensed or in training in the United States. These entries are listed alphabetically by city and state of record and include the following information: name of medical school and date of graduation, date of first licensure, current address, self-selected primary and secondary specialties, board certifications, AMA Physician’s Recognition Awards, and type of practice (resident in training, direct patient care, teaching/research/administration, retired, or other).

We selected two matched comparison groups. The first comparison group (C-1) comprised, for each disciplined physician, the next physician listed in the AMA directory who matched the disciplined physician’s location (city, town, or rural area), type of practice (patient care, administrative, academic/research, retired, or in training), and gender. The second group (C-2) comprised, for each disciplined psychiatrist, the next psychiatrist in the AMA directory who matched the disciplined physician on the listed factors. When an appropriate match could not be made from physicians listed in the disciplined physician’s exact city or town, appropriate matches (city, town, or rural area) were found in localities within the same state. For each comparison group, the directory information was recorded, as was done for the disciplined physicians.

Physicians who surrendered their California licenses while under investigation for alleged wrongdoing are also listed in Action Report. Although the nature of the allegation is not stated, this publicly available information was obtained by request from the Medical Board of California. The same directory information as obtained for the other groups was recorded for each of the physicians listed within the same 30 months.

In the analyses, we used SPSS for Windows (version 7.5) to compute bivariate associations between each dependent variable and the hypothesized predictor variable. Pearson’s chi-square statistics were computed to detect significant associations.

Results

During the 30 months of the study, 584 physicians (of approximately 104,000 licensed by the state of California) were disciplined by the Medical Board of California, a rate of about 0.25% per year. Of these, 75 (12.8%) listed their primary specialty as psychiatry. Of the 584 C-1 comparison physicians, 42 (7.2%) listed themselves as psychiatrists; the difference between the number of psychiatrists in the disciplined and nondisciplined groups was highly significant (χ2=9.73, df=1, p<0.001). Not included as psychiatrists in subsequent analyses were an additional nine (1.5%) disciplined physicians who claimed psychiatry as their second specialty versus only three (0.5%) in the C-1 group (χ2=2.44, df=1, n.s.).

The 75 disciplined psychiatrists included six (8.0%) women; although data for California physicians are not available, nationally in 1995, 27.3% of all psychiatrists were women (16) (p=0.0002, one-sample test for a binomial proportion). Disciplined and nondisciplined psychiatrists had been out of school a mean of 27.9 years (SD=8.8); they did not differ significantly on international medical graduate status (13 versus 14, respectively) (χ2=0.00, df=1, n.s.) or board certification (43 versus 46) (χ2=0.11, df=1, n.s.). However, there were more than twice as many disciplined as nondisciplined psychiatrists who claimed child psychiatry as their first or second specialty (20 versus nine, respectively) (χ2=4.27, df=1, p<0.05); there were far fewer disciplined than nondisciplined psychoanalysts (zero versus eight, respectively) (χ2=6.47, df=1, p<0.01).

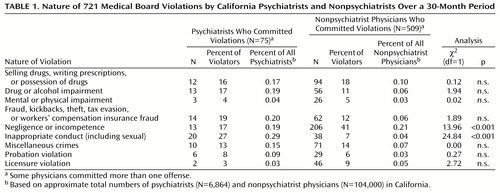

Type of offenses leading to discipline are given in Table 1 for 584 physicians who were disciplined: 75 psychiatrists and 509 nonpsychiatrists. Of the 721 offenses committed by all 584 physicians, 58 (8.0%) were of a sexual nature. Psychiatrists (N=20) made up 34% of all physicians disciplined at least in part for sexual relationships or other inappropriate personal contact with patients and were less likely to be charged with negligence or incompetence. Both of these comparisons were significant at the Bonferroni-adjusted significance level of 0.05.

Of disciplined psychiatrists, 14 (18.7%) were disciplined for more than one offense, compared with 100 (19.6%) disciplined nonpsychiatrists (χ2=0.002, df=1, n.s.). The severity of discipline for 75 psychiatrists and 509 nonpsychiatrists was as follows: letter of reprimand: 17 (23%) of psychiatrists versus 104 (20.4%) of nonpsychiatrists; stayed revocation: 28 (37.3%) versus 236 (46.4%), respectively; temporary license suspension (unable to practice): 11 (14.7%) versus 65 (12.8%); and license revocation: 19 (25.3%) versus 109 (21.4%). Although the overall severity of discipline was slightly greater for psychiatrists than for nonpsychiatric physicians, the difference was not significant (χ2=1.66, df=3, n.s.).

Of the 159 physicians who surrendered their California licenses while under investigation, 21 (13.2%) were psychiatrists; among them were five child psychiatrists, one psychoanalyst, and one addiction psychiatrist. The psychiatrists who surrendered their licenses were being investigated for a total of 30 violations, including negligence or incompetence (N=8), violations of sexual boundaries (N=10), fraud (N=3), and impairment (mental, physical, or substance abuse) (N=5).

Discussion

Both of our initial study predictions were fulfilled. Psychiatrists were far more likely than the general population of physicians to receive some form of discipline from the California Medical Board. Although the reasons behind these disciplinary actions were varied, inappropriate sexual contact with patients was especially prominent. However, even after eliminating 16 psychiatrists and 26 other physicians who were disciplined solely for violating sexual boundaries, psychiatrists were still overrepresented among disciplined physicians (χ2=4.69, df=1, p<0.05). In addition, psychiatry was overrepresented among those physicians who relinquished their licenses while under investigation. Disciplined physicians were more likely than nondisciplined physicians to list psychiatry as their second specialty. Donaldson (17) similarly reported that psychiatrists constituted 22% of physicians referred for possible disciplinary action to the medical staff of a large National Health Service hospital in England.

Although our data do not permit definitive conclusions, psychiatrists may be at a greater risk than most physicians for discipline for misconduct other than sexual, especially drug and alcohol problems, fraud, and theft. Pontell et al. (18) found that psychiatrists constituted 18.4% of physicians sanctioned by the federal government for Medicare and Medicaid fraud or abuse. Psychiatrists were also overrepresented in the Gallegos et al. 1992 report (15%) (12) on chemically dependent physicians and in Bissell and Skorina’s report (22%) (11) on chemically dependent female physicians. (We note that Talbott et al. [13] reported that psychiatrists were not overrepresented in their review of 1,000 chemically impaired Georgia physicians.) However, negligence and incompetence were not found to be high for psychiatrists; previous studies (2–4, 19) have even reported low malpractice claims rates for psychiatrists. On balance, psychiatrists’ risk for medical board action may extend across several areas of ethical conduct.

The area of greatest concern percentage-wise, sexual misconduct, has been addressed in at least three previous controlled studies. Enbom and Thomas (8) found that psychiatrists received the second highest number of complaints per 100 licensed physicians and the largest number resulting in board actions. Dehlendorf and Wolfe (7) surveyed disciplinary actions for sex-related offenses from nearly every state and jurisdiction and found that psychiatrists had proportionately the most such actions of any medical discipline, about twice as many as the runner-up, obstetrics-gynecology. Goodwin et al. (9) noted that in the 1980s, fully 3% of Wisconsin’s psychiatrists had been disciplined for sexual misconduct. Even these figures may underreport the magnitude of the problem, considering the finding of Gartrell et al. (20) that 7% of male and 3% of female psychiatrists reported having sexual contact with their patients.

Several factors could increase psychiatrists’ risk of sexual boundary violations. They often work in isolation, out of view of other professionals. Also, psychiatrists have more personal contact, longer and more sessions with individual patients, hence more opportunity to become intimate with them. Of course, we cannot assume a direct correlation between discipline and misconduct; patients may be more likely to report sexual misconduct for physicians of particular specialties. However, although we have no information on which to make judgments, we wonder whether the nature of the problems that may render psychiatric patients especially vulnerable to inappropriate caregiver relationships may also make them more reluctant than most to report sexual contact. We acknowledge this problem with interpretation and urge further study to resolve this ambiguity.

Impressive and somewhat puzzling in our data was the significant absence of psychoanalysts from the ranks of disciplined physicians (one surrendered his license while under investigation but not for sexual boundary violations). Perhaps the additional prolonged training of psychoanalysts sensitizes them to the need for distance from their patients. Or is it merely the practical effect of having, on average, far fewer patients, hence less opportunity for problematic interaction? Neither conjecture adequately explains the absence of causes of discipline other than sexual boundary violations for psychoanalysts. Indeed, the only reference in the literature is a contrary note by Gartrell et al. (20) that psychiatrists who admitted having sexual contact with their patients were especially likely to have undergone personal psychotherapy or psychoanalysis.

Dehlendorf and Wolfe (7) reported that child specialists were disciplined for sex-related offenses to about the same extent as were other psychiatrists, whereas in our study they were nearly three times more at risk. This discrepancy could be partly explained by different methods of ascertainment. We scored as a child psychiatrist any person who listed the specialty as either a first or second choice, whereas Dehlendorf and Wolfe included only those for whom it was the primary self-selected specialty. Using their definition, we would identify only 11 (15.0%) disciplined child psychiatrists as compared with four (5.3%) nondisciplined child psychiatrists in the C-2 comparison group. Although the ratio remains approximately the same, its significance disappears (χ2=2.66, df=1, n.s.). However, the high rate we report is supported by finding five (24.0%) child specialists among the 21 psychiatrists who surrendered their California licenses. If our finding turns out to be valid, we have no adequate explanation for it.

Reflecting the Medical Board of California’s focus on rehabilitation, the licenses of only 19 psychiatrists were revoked outright; an additional 11 received license suspension. Some revocations came only after a physician refused to cooperate with previous medical board sanctions. In nearly every case, revocation was for a serious offense: drug misuse (personal or patient), sexual contact, incapacity, negligence or incompetence, or a failed prior attempt at rehabilitation. The severity of discipline for psychiatrists was not significantly different from that of other physicians. We need to follow up psychiatrists whose revocations were stayed to learn the extent to which they continue to offend.

Supporting the generalizability of our findings are these facts: California has under license 15% of all physicians in the country, it occupies a median position in the national spectrum on the Federation of State Medical Boards’ composite action index (1), and 27% of Medical Board of California actions were in response to discipline initiated by other states. Nonetheless, these findings should be replicated in other jurisdictions. Their implications are important enough, however, to stimulate a discussion of possible remedies. More laws or harsher discipline are probably not a viable answer (21). Garfinkel et al. (22) expressed concern for the well-being of patients who are drawn into unwanted legal proceedings by Canadian law, which now requires health care professionals to report any instance of physician sexual contact with patients.

Rather, the profession should further explore education as a means of preventing undesirable behavior. The recommendation of Miller et al. (23) that “the foundations for professional integrity in clinical research…be laid in medical school” would seem to apply equally well to the ethics of clinical psychiatry. Although medical school is where we should foster awareness of the issues, temptations, and consequences of behavior, this is not currently the norm: over one-half of all physicians may have had no exposure to the problems of sexual contact with patients (24). Residency curricula may include only an hour or 2 of discussion concerning inappropriate personal relationships. Such a brief exposure to vital concepts is probably insufficient; indeed, our findings as regards psychoanalysts could be interpreted in favor of greatly expanding education concerning sexual boundary issues. Self et al. (25) reported that exposure to 20 hours or more of small-group, case-study discussion significantly raised the moral reasoning skills of students. Additional discussion topics might profitably include practical issues of fraud, falsification of credentials, and other temptations that medical practitioners may face. Ethicists might even emphasize the duty of physicians to counsel and, when necessary, compel colleagues to avail themselves of programs to treat impaired physicians.

Garfinkel et al. (22) emphasized that academic psychiatrists should openly discuss boundary issues and, by their own examples, model desired behavior. Departments of psychiatry could sponsor reviews of the ethics of medical practice; vignettes from medical board files could become standard fare on psychiatry recertification exams to help physicians “maintain heightened awareness about liability as an issue” (26). Additional educational opportunities might include ads, articles, and admonitions in professional journals to address clinician substance use; promulgation of ethics codes by means of membership renewal for state and local psychiatric societies; and, as a requirement for renewal of state medical licenses, continuing medical education that focuses on unethical or illegal behavior.

The evidence is scant that education can actually prevent illegal and unethical behavior. Quadrio (27) somewhat gloomily observed that nothing (improved training, licensing, therapy, or supervision) can absolutely protect against future sexual contact with patients. But at the dawn of a new millennium, we perceive an opportunity to profit from the experiences of the last hundred years or more. And it must be asked, what alternative do we have?

|

Received Aug. 27, 1999; revisions received April 19 and Aug. 8, 2000; accepted Oct. 4, 2000. From the Department of Psychiatry, Temple University, Philadelphia; and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Alabama at Birmingham. Address reprint requests to Dr. Morrison, Department of Psychiatry, Oregon Health Services University UHN 80, 3181 Sam Jackson Park Rd., Portland, OR 97201; [email protected] (e-mail).The authors thank Candice Cohen of the California Medical Board for her help in data collection.

1. Morrison J, Wickersham P: Physicians disciplined by a state medical board. JAMA 1998; 279:1889–1893Google Scholar

2. Slawson PF, Guggenheim FG: Psychiatric malpractice: a review of the national loss experience. Am J Psychiatry 1984; 141:979–981Link, Google Scholar

3. Schwartz WB, Mendelson DN: Physicians who have lost their malpractice insurance. JAMA 1989; 262:1335–1341Google Scholar

4. Taragin MI, Sonnenberg FA, Karns E, Trout R, Shapiro S, Carson JL: Does physician performance explain interspecialty differences in malpractice claim rates? Med Care 1994; 7:661–667Google Scholar

5. Bloom JD, Williams MH, Kofoed L, Rhyne C, Resnick M: The malpractice claims experience of physicians investigated for inappropriate prescribing. West J Med 1989; 151:336–338Medline, Google Scholar

6. Kofoed L, Bloom JD, Williams MH, Rhyne C, Resnick M: Physicians investigated for inappropriate prescribing by the Oregon Board of Medical Examiners. West J Med 1989; 150:597–601Medline, Google Scholar

7. Dehlendorf CE, Wolfe SM: Physicians disciplined for sex-related offenses. JAMA 1998; 279:1883–1888Google Scholar

8. Enbom JA, Thomas CD: Evaluation of sexual misconduct complaints: the Oregon Board of Medical Examiners, 1991 to 1995. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997; 176:1340–1348Google Scholar

9. Goodwin J, Bemmann K, Zweig J: Physician sexual exploitation: Wisconsin in the 1980s. J Am Med Wom Assoc 1994; 49:19–23Medline, Google Scholar

10. Shore JH: The impaired physician: four years after probation. JAMA 1982; 248:3127–3130Google Scholar

11. Bissell L, Skorina JK: One hundred alcoholic women in medicine. JAMA 1987; 257:2932–2944Google Scholar

12. Gallegos KV, Lubin BH, Bowers C, Blevins JW, Talbott GD, Wilson PO: Relapse and recovery: five to ten year follow-up study of chemically dependent physicians: the Georgia experience. Md Med J 1992; 41:315–319Medline, Google Scholar

13. Talbott DG, Gallegos KV, Wilson PO, Porter TL: The medical association of Georgia’s impaired physicians program. JAMA 1987; 257:2927–2930Google Scholar

14. Medical Board of California 1996–7 Annual Report. Sacramento, Medical Board of California, Oct 1997Google Scholar

15. American Medical Association: Directory of Physicians in the United States, 35th ed. Chicago, AMA, 1996Google Scholar

16. American Medical Association: Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the United States. Chicago, AMA, 1997Google Scholar

17. Donaldson LJ: Doctors with problems in an NHS workforce. Br Med J 1994; 308:1277–1282Google Scholar

18. Pontell HN, Jesilow P, Geis G, O’Brien MJ: A demographic picture of physicians sanctioned by the federal government for fraud and abuse against Medicare and Medicaid. Med Care 1985; 23:1028–1031Google Scholar

19. Hamolsky MW, Deary NS, Aronson SM: The physicians of Rhode Island: a summary of disciplinary actions taken by the board of medical licensure and discipline (1987–1998). Med Health J Rhode Island 1998; 81:326–327Google Scholar

20. Gartrell N, Herman J, Olarte S, Feldstein M, Localio R: Psychiatrist-patient sexual contact: results of a national survey, I: prevalence. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:1126–1131Google Scholar

21. Self DJ: Moral integrity and values in medicine. Theor Med 1995; 16:253–264Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Garfinkel PE, Dorian B, Sadavoy J, Bagby RM: Boundary violations and departments of psychiatry. Can J Psychiatry 1997; 42:764–770Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Miller FG, Rosenstein DL, DeRenzo EG: Professional integrity in clinical research. JAMA 1998; 280:1449–1454Google Scholar

24. Gartrell NK, Milliken N, Goodson WH III, Thiemann S, Lo B: Physician-patient sexual contact: prevalence and problems. West J Med 1992; 157:139–143Medline, Google Scholar

25. Self DJ, Olivarez M, Baldwin DC Jr: The amount of small-group case-study discussion needed to improve moral reasoning skills of medical students. Acad Med 1998; 73:521–523Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Gutheil TG: Risk management at the margins: less-familiar topics in psychiatric malpractice. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1994; 2:214–224Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Quadrio C: Sex and gender and the impaired therapist. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1992; 26:346–363Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar