The Prevalence of Clinically Recognized Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in a Large Health Maintenance Organization

Abstract

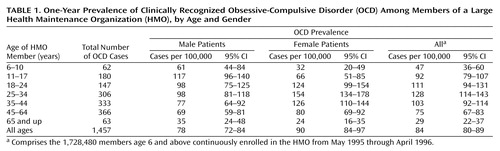

OBJECTIVE: Little is known about the prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) as recognized in clinical settings. The authors report data on the prevalence of clinically recognized OCD in a large, integrated, group practice health maintenance organization (HMO). METHOD: The authors examined the database of outpatient diagnoses for the 1.7 million people (age ≥6) in the San Francisco Bay Area and Sacramento who were continuously enrolled in Kaiser Permanente from May 1995 through April 1996. OCD diagnoses were confirmed by chart review. RESULTS: The 1-year prevalence of clinically recognized OCD was 84/100,000 (95% confidence interval: 80–89/100,000), or 0.084%. It varied among the 19 clinics within the HMO but was nowhere higher than 150/100,000. Prevalence was higher among women than among men but was higher among boys than among girls. Above age 65, OCD prevalence decreased markedly in both genders. Period prevalence rates increased by 60% as the length of the study period doubled from 1 to 2 years, more than would be expected for a chronic disease requiring regular care. About three-quarters of both children and adults with OCD had comorbid psychiatric diagnoses; major depression was common in both groups. CONCLUSIONS: Although previously reported prevalences of 1%–3% from community studies may have included many transient or misclassified cases of OCD not requiring treatment, the very low prevalence of clinically recognized OCD in this population suggests that many individuals suffering from OCD are not receiving the benefits of effective treatment.

Little is known about the prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) as diagnosed and treated in clinical settings. Although several studies have determined through interviews the prevalence of OCD in community or primary care populations (1–9), little is known about rates of clinical recognition and treatment. The suffering, functional impairment, and economic cost due to OCD are substantial. Untreated OCD is associated with higher rates of unemployment, less work productivity, lower rates of marriage, and adverse effects upon family members (9–13). Moreover, OCD is associated with high rates of major depression, social phobia, and other mental disorders (14–16) and poor long-term social adjustment (17). Fortunately, effective pharmacological and behavioral treatments are available (18).

The expansion of managed care has raised concerns about incentives to underserve patients with chronic mental disorders. However, large health maintenance organizations (HMOs) are promising settings for improving the detection and treatment of chronic disorders like OCD. For example, HMO data management systems make outreach programs feasible for members who have been diagnosed but are not receiving care.

We report, to our knowledge, the first population-based estimates of the prevalence of clinically recognized OCD, derived from the population served by an integrated group practice HMO, the Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program of Northern California.

Method

Study Population and Health Plan Benefits

The study population comprised the 1,728,480 people age 6 years and above who were continuously enrolled in Kaiser from May 1995 through April 1996 (the primary study period) and were served by any of 19 Kaiser clinics located in the San Francisco Bay Area and Sacramento, Calif. Kaiser provides comprehensive health care to approximately 30% of the general population in these areas. The Kaiser population is diverse with respect to race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status, although the poor, the unemployed, and the aged are somewhat underrepresented (19).

During the study period, Kaiser mental health benefits for most members included 45 inpatient days, 20 visits per year for psychotherapy, unlimited brief visits with a psychiatrist concerning medication, and unlimited visits for alcohol and substance abuse treatment. The pharmacy benefit for most members included a copayment, often $5 per prescription. Members could refer themselves to a psychiatry clinic without referral from a “gatekeeper.” Approximately 20% of members had access to additional insurance covering mental health services provided outside of Kaiser.

Ascertainment of OCD

Since April 1995, Kaiser health care providers have used specialty-specific encounter forms to indicate diagnoses or other reasons for each outpatient visit. These checklists are scanned into the Outpatient Summary Clinical Record database. OCD is one of 80 diagnoses on the forms used in the psychiatry department. Forms used in other departments do not include a box for OCD, but we believe it to be rare for OCD to be diagnosed exclusively in other departments without any visits to the psychiatry department.

There were 2,043 individuals from the study population who had an OCD diagnosis according to the Outpatient Summary Clinical Record database during the primary study period. Chart reviews were completed for 1,771 (87%). The OCD diagnosis was confirmed in 1,276 (72%) of the chart reviews and disconfirmed in 495 (28%). Confirmed cases of OCD were those in which the chart contained a clinical OCD diagnosis during the study period or when the clinician recorded symptoms and impairment that met criteria for “definite” or “probable” OCD according to diagnostic checklists. The OCD checklists were similar to DSM-IV criteria. “Definite” cases of OCD consisted of patients who exhibited obsessions or compulsions, as listed in the symptom checklist of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (20), with documentation that they caused marked distress, occupied at least 1 hour per day, or significantly interfered with the patient’s role functioning. “Probable” cases of OCD consisted of patients who exhibited obsessions or compulsions but lacked adequate documentation to determine the degree of distress, time occupied, or dysfunction. The chart reviewers did not count toward an OCD diagnosis symptoms that were better explained by other disorders.

One author (L.M.K.) rereviewed 87 randomly selected charts and assigned patients to “definite,” “probable,” “possible,” and “no OCD” categories while blind to the chart reviewers’ findings. He agreed with the chart reviewer on 30 of 31 patients first categorized as having “definite” OCD but on only 38 of the 56 others. Application of category-specific agreement rates to the entire chart-reviewed sample had very little effect on estimated OCD prevalence.

We did not review the charts of 272 (13%) of the individuals with OCD diagnoses according to the Outpatient Summary Clinical Record primarily because the charts were unavailable. To estimate how many of these really had OCD, we fitted a logistic regression model to data from the chart-reviewed cases (whereby the odds of confirmation were a function of the number of OCD visits, the clinic visited, age, and gender) and applied the resulting regression coefficients to the unreviewed cases. The unreviewed patients on average had fewer visits and visited clinics at which lower proportions of Outpatient Summary Clinical Record diagnoses of OCD were confirmed. The logistic regression model yielded an expectation that 181 (67%) of the 272 unreviewed patient diagnoses would have been confirmed. Altogether then, we estimate that 1,457 Kaiser members (181 expected plus 1,276 confirmed) had clinically recognized OCD from May 1995 through April 1996, which was the numerator for our primary 1-year prevalence estimate.

To investigate possible underreporting of OCD in the Outpatient Summary Clinical Record database, we reviewed the charts of 57 patients whose Outpatient Summary Clinical Record did not include an OCD diagnosis but who received both 1) a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor during this primary study period, and 2) an Outpatient Summary Clinical Record OCD diagnosis during the subsequent 12 months. Two of the 57 patients met the aforementioned criteria for “possible” OCD during the primary study period; none met criteria for “definite” or “probable” OCD. It is also possible that some patients were given a vague diagnosis (such as adjustment disorder) because of concern that an OCD diagnosis would be stigmatizing, but we believe this occurs rarely.

“New” OCD cases were patients who had no Outpatient Summary Clinical Record OCD diagnosis in the 6 months preceding the study period; “continuing” OCD cases were patients who had at least one OCD diagnosis in the 6 months preceding the study period.

Statistical Analysis

We determined the number of individuals in the study population who had clinically detected OCD. One-year period prevalence rates with asymmetrical approximate 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the entire study population and for age and gender subgroups. Exact binomial 95% CIs were calculated for the proportions of OCD patients who had selected comorbid conditions. Logistic regression was used to assess variation in OCD prevalence across the 19 clinics, with adjustment for the age and gender of the clinic populations. Gender differences in prevalence were assessed with the chi-square test. The Kaplan-Meier estimator (for censored survival data) was used to examine the distribution of time until the next psychiatric visit among OCD patients who had not been seen for 15 months. SAS software (21) was used for all computations.

Ascertainment of Severity

For each patient with definite or probable OCD, the chart reviewers judged the severity of OCD at the first visit in the study period. OCD was defined as “mild” when symptoms occupied up to 2 hours per day, caused the patient only mild to moderate distress, and caused slight interference with role functioning. OCD was defined as “moderate” when symptoms occupied between 2 and 6 hours per day, caused moderate or severe distress, and interfered substantially with functioning (but the patient still met most responsibilities). In “severe” cases, the symptoms occupied more than 6 hours per day, were very disturbing to the patient, and the patient either did not perform or performed poorly some expected role functions.

Sensitivity of Prevalence to Observation Period and Regularity of Care

If OCD is often not chronic or if chronic OCD is often recognized only sporadically, then the period prevalence of clinically recognized OCD will increase markedly with period length. We examined period prevalence in relation to period length among subjects who were continuously enrolled in the HMO for 30 months, assuming that 72% of the diagnoses recorded in the Outpatient Summary Clinical Record database would be confirmed by chart documentation, as we found for the 1,771 charts reviewed for the primary 12-month study period.

We later extended follow-up for an additional 38 months to examine the extent to which care for OCD is ongoing or sporadic. We summarized patterns of visits to the psychiatry department and prescriptions for OCD medications among the 967 patients whose OCD was confirmed by chart review during the period from May 1995 through October 1997 and who remained enrolled in the HMO through December 2000.

Results

Prevalence

The 1-year prevalence of clinically recognized OCD was 84 cases per 100,000 HMO members (95% CI: 80–89 per 100,000) (Table 1), or 0.084%. Recognized OCD was more prevalent among male than female patients among subjects who were below age 18 (χ2=19.6, df=1, p<0.0001); however, up to age 65, OCD was less prevalent among adult men than among adult women (χ2=24.9, df=1, p<0.0001). Among OCD patients younger than age 18, the male/female ratio was 1.90; among adult OCD patients the male/female ratio was 0.68. Prevalence among male patients was highest in the 11–17 age group; prevalence among female patients was highest in the 25–34 age group. Above age 65, the prevalence of clinically recognized OCD markedly decreased in both genders.

Prevalence rates across the 19 Northern California clinics ranged from 31 to 150 per 100,000 members, with the coefficient of variation=35.7% (the coefficient of variation expresses the standard deviation as a percentage of the mean). Four facilities had relatively high prevalence rates (≥111/100,000); three had relatively low rates (≤45/100,000). After adjustment for the small age and gender differences among the populations served by the 19 clinics, the interclinic variation in prevalence remained more than could be due to chance alone (logistic regression: likelihood ratio χ2=216, df=18, p<0.0001).

Chronicity of Clinically Recognized OCD

Period prevalence (per 100,000) increased from 84 to 109 as the period was lengthened from 12 months to 18 months and increased to 134 and 160 as the period was lengthened to 24 months and 30 months, respectively. These increases are more than would be expected for a chronic disease requiring regular care in a relatively stable population. To examine the contribution of sporadic treatment to the increase in period prevalence rates, we assessed the extent to which patients continued to receive clinical recognition and care after the period used for case ascertainment. During the 38 months available for additional follow-up, 43% of the patients (413 of the 967 who remained in the health plan) had no OCD diagnoses recorded in the outpatient summary clinical record; 19% had no visits to the psychiatry department at all. There were 420 patients (43%) who had at least one visit to the psychiatry department in each of the 3 calendar years from 1998 through 2000. The median number of visits to the psychiatry department for the 967 patients was six.

We cannot determine whether the marked increase in prevalence with longer observation periods was due to OCD being less chronic than is believed or because patients with chronic OCD receive sporadic care. However, to begin quantifying the gaps between episodes of care (which determine the extent to which period prevalence increases with period length), we examined the propensity to return to the psychiatry department for the 609 patients (63%) who went without a visit to the psychiatry department for 15 months. After 15 months away from the psychiatry department, 20% returned within 6 months, 36% within 1 year, 49% within 2 years, and 57% within 3 years.

Some patients’ care may appear sporadic if they regularly receive medications and telephone follow-up without regular visits. So, for the 798 patients who received any OCD medications from May 1995 through October 1997, we examined prescriptions filled during the subsequent 38 months of extended follow-up. There were 36% who received OCD medications throughout the extended follow-up period (days supply >844, more than 75% of the 38 months), and an additional 14% received OCD medications for more than one-half of the period (days supply >562); 23% received no OCD medications during the period.

Comorbid Psychiatric Conditions

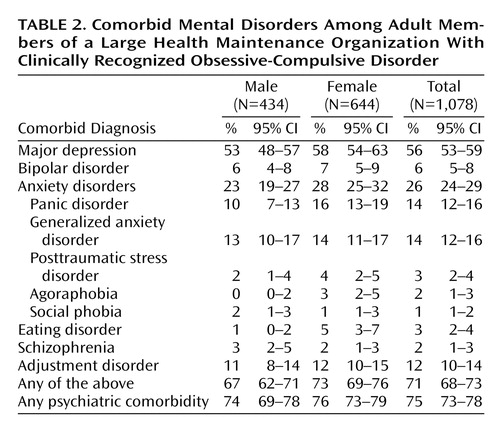

About 25% of adults whose OCD was confirmed by chart review had no comorbid psychiatric condition recorded in the Outpatient Summary Clinical Record database during the study period (Table 2); 37% had one, and 38% had two or more. Men and women exhibited no substantial differences in these percentages. The most commonly diagnosed comorbid conditions were major depression, other anxiety disorders, and adjustment disorder. Among the comorbid anxiety disorders, panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder were the most common. Six percent of the patients also had bipolar disorder. Except for eating disorders (diagnosed in 5% of women), the rates of specific comorbid conditions in men and women exhibited no striking differences.

Like adults, 25% of child and adolescent OCD patients had no diagnosed comorbid psychiatric condition (Table 3). Nearly one-quarter of this age group (23%) had one comorbid condition, and 53% had two or more. Attention deficit disorder was as common as major depression but was diagnosed twice as often in male as in female patients. Comorbid oppositional defiant disorder and overanxious disorder were diagnosed in nearly one in six of this age group. Comorbid eating disorders were diagnosed in one in nine female patients. Tourette’s disorder was common in male patients.

Severity of OCD

At the first visit in the study period, only about one in 13 new OCD cases among children and adolescents and one in 23 among adults were judged by the chart reviewers to meet criteria for “severe” OCD (Table 4). If we ignore the 31% of patients whose charts contained inadequate documentation to make this judgment, these figures rise to one in nine children and adolescents and one in 15 adults. The proportions of mild, moderate, and severe cases in patients with continuing OCD closely resembled those of the patients with new-onset OCD. Among those in whom OCD severity ratings were ascertainable, more than one-half of the child and adolescent patients and nearly three-quarters of the adult patients were judged to have “mild” OCD.

Discussion

The prevalence of clinically recognized OCD in a large HMO comprising 19 clinics in Northern California was less than one-tenth as high as the 1%–3% estimates of OCD prevalence reported by community and primary care studies, estimates that include OCD that has never been clinically recognized (1–3, 9). However, many of the cases of OCD counted in community and primary care prevalence estimates have been found to be transient, subthreshold, or otherwise misclassified and therefore not requiring OCD treatment (22–25). For example, two diagnostic assessments done a year apart on a sample of participants at four of the five sites in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study found kappa statistics from 0.16 to 0.25. Among 291 patients rated as having lifetime OCD at wave 1, only 9% (N=26) were so rated at wave 2. Psychiatric reappraisal of adults who had been diagnosed with OCD in a Canadian epidemiological study dropped the OCD prevalence from 3.1% to 0.6% (25).

Given this evidence of misclassification and instability of OCD diagnoses in community and primary care studies, their prevalence estimates—which include point, period, and lifetime prevalence estimates all in the range of 1%–3%—must be used with caution. If we adjust for misclassification and instability, we may infer that the prevalence of OCD is more likely in the range of 0.3% to 1.0% (acknowledging that these studies may include false negatives). However, even if the true prevalence of OCD in our study population (unrecognized plus recognized) is in this lower range of 0.3% to 1.0%, then our very low prevalence of clinically recognized OCD (0.084%) still suggests that only a minority (8%–28%) of OCD cases are clinically recognized. The long delays observed from the onset of OCD symptoms and impairment until diagnosis and treatment (a mean of 7 years in one study [26] and 10 years in another [27]) also suggest that many people who have OCD are not receiving treatment.

We found that most patients with clinically recognized OCD received episodic care (28) that included long periods (>15 months) without any mental health care. While the severity of OCD typically waxes and wanes, the prevailing wisdom is that the underlying disorder is chronic in most individuals who seek treatment (9, 29–31); thus, regular care is appropriate for many years and perhaps for life. Further research is needed regarding OCD patients who have received no clinical recognition or treatment for more than a year. If most have mild or absent OCD symptoms and impairment, then we may question either the validity of the OCD diagnosis or the prevailing wisdom that OCD is chronic. Just as many patients diagnosed in epidemiologic studies may be misclassified or transient, so may be clinically diagnosed patients, especially among those who seek mental health care only once or twice.

On the other hand, high levels of suffering and impairment may exist among patients whose treatment has been brief or sporadic. If so, we need to better understand the reasons for treatment discontinuation and for delays in restarting treatment. The reasons may include ignorance about the disorder and the efficacy of treatment, shame about symptoms, or poor access to mental health services. Our chart review of 1,276 OCD patients revealed that episodes of OCD care rarely ended with an indication that treatment had been completed or that future visits would not be needed. Episodes usually ended without an explicit explanation in the chart.

Further research is also needed to explain why the prevalence of clinically recognized OCD decreases markedly among older adults. Perhaps the prevalence of unrecognized OCD decreases less markedly: the drop-off after age 65 seen in Table 1 is steeper than was observed after this age in data from research interviews conducted by the ECA (5) or at the Canadian site of the Cross National Collaborative Study (32). The prevalence of nonfatal chronic illnesses generally increases with age, most steeply through the age range when onset is most common. However, the prevalence of clinically recognized OCD appears to reach its peak when it would be expected to be rising most rapidly: in adolescence among male individuals and in the younger adult ages among female individuals. Even if OCD is usually chronic, the propensity to seek care may peak near illness onset and then decline. Perhaps many patients adjust to their illness with age.

The amount of variation in clinically recognized OCD observed across 19 Northern California clinics is comparable to the variation in OCD observed across seven geographical populations (United States, Canada, Germany, Taiwan, Korea, New Zealand, and Puerto Rico) ascertained by research interviews (32). Across the 19 clinics, the range was 0.3 to 1.5 per 1,000 (coefficient of variation=35.7%); across the seven geographical populations the range was 0.4 to 1.8 per 100 (coefficient of variation=36.2%). While our prevalence estimates are much lower because of our omission of clinically unrecognized OCD, the amount of interarea variation is similar. If the prevalence of OCD is roughly similar across diverse populations, then much of the variation in clinically recognized OCD across our 19 clinics can be attributed more to differences in diagnostic practices than to population differences.

The prevalence of comorbid psychiatric conditions in adult patients with OCD (Table 2) is consistent with the high rates of comorbid disorders reported in epidemiological (5) and clinical (9) studies. These high rates imply that OCD patients should be carefully assessed for comorbid conditions and that the treatment of patients in clinical practice may be more complicated than in clinical trials, which employ numerous exclusion criteria (18). Comorbid diagnoses may be more common with clinically recognized than with unrecognized OCD because the suffering and impairment resulting from the comorbid illnesses increase the propensity to seek care.

The child and adolescent patients in our study had a strikingly high rate of attention deficit disorder and high rates of Tourette’s disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and overanxious disorder. Similarly high figures have been reported in a series of consecutively referred children and adolescents with OCD, unaffected by exclusion criteria (33, 34). Since most patients with OCD are also diagnosed with other mental disorders, misclassification among comorbid mental disorders or misclassification of subthreshold or transient symptoms may contribute to the aforementioned instability of OCD diagnoses. For example, the ruminations of depressed patients may be mistaken for obsessions. Unfortunately, our methods of summarizing the comorbid diagnoses (without chart review) do not permit us to note change over time in the clinician’s diagnostic assessment. If a preliminary OCD diagnosis was changed to major depressive disorder, we may be misreporting this as an OCD case with comorbid depression.

We were surprised that the proportion of severe cases was not higher among new than among continuing OCD cases, since the majority of the charts indicated improvement between the first and last visits during the study period. The inability of the chart reviewers to make a severity judgment in one-third of cases suggests that our severity criteria and chart review methods were not sensitive to clinical change in severity.

The underrecognition of OCD, like that of other mental disorders, raises policy questions concerning screening and education. The cost-effectiveness of screening the entire population is problematic in view of the apparently high rate of subthreshold, transient, and misclassified cases of OCD in epidemiological studies. A more cost-effective approach might target patients with highly comorbid conditions and patients with a past diagnosis of OCD but no recent OCD care. Screening and outreach to these patients should be feasible in HMOs like Kaiser that have automated databases and an integrated delivery system. Furthermore, programs of patient education and public education may also encourage individuals with OCD to seek and sustain care.

Conclusions

The 1-year prevalence of clinically recognized OCD within a large HMO was approximately 84/100,000 (less than one-tenth of 1%). While community studies finding OCD prevalences of 1%–3% may have found many transient or misclassified cases of OCD that were not in need of treatment, the low prevalence of clinically recognized OCD suggests that many individuals suffering from OCD are not receiving the benefits of effective treatment.

|

|

|

|

Received Oct. 27, 2000; revision received April 20, 2001; accepted June 20, 2001. From the Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program of Northern California; and the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University Medical Center, Stanford, Calif. Address reprint requests to Mr. Fireman, Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program of Northern California, 3505 Broadway, Oakland, CA 94611; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a grant from Solvay Pharmaceuticals. The authors thank Graciela Bonilla and Virginia Browning for conducting the chart reviews and Elisabeth Gruskin and Joe Selby for their comments on an earlier version of this article.

1. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:85-94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Schulberg HC, Saul M, McClelland M, Ganfuli M, Christy W, Frank R: Assessing depression in primary medical and psychiatric practices. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:1164-1170Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Von Korff M, Shapiro S, Burke JD, Teitlebaum M, Skinner EA, German P, Turner RW, Klein L, Burns B: Anxiety and depression in a primary care clinic: comparison of Diagnostic Interview Schedule, General Health Questionnaire, and practitioner assessments. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:152-156Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Leon AC, Olfson M, Broadhead E, Barrett JE, Blacklow RS, Keller MB, Higgins ES, Weissman MM: Prevalence of mental disorders in primary care. Arch Fam Med 1995; 4:857-861Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Karno M, Golding JM, Sorenson SB, Burnam A: The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in five US communities. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:1094-1099Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Zinbarg RE, Barlow DH, Leibowitz M, Street L, Broadhead E, Katon W, Roy-Byrne P, Lepine J-P, Teherani M, Richards J, Brantley PJ, Kraemer H: The DSM-IV field trial for mixed anxiety-depression. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1153-1162Link, Google Scholar

7. Olfson M, Fireman B, Weissman MM, Leon AC, Sheehan DV, Kathol RG, Hoven C, Farber L: Mental disorders and disability among patients in a primary care group practice. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1734-1740Link, Google Scholar

8. Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD Jr, Rae DS, Myers JK, Kramer M, Robins LN, George LK, Karno M, Locke BZ: One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States: based on five Epidemiologic Catchment Area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:977-986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL: The epidemiology and clinical features of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1992; 15:743-758Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Koran LM, Thienemann ML, Davenport R: Quality of life for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:783-788Link, Google Scholar

11. Leon AC, Portera L, Weissman MM: The social costs of anxiety disorders. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166(suppl 27):19-22Google Scholar

12. Calvocoressi L, Lewis B, Harris M, Trufan SJ, Goodman WK, McDougle CJ, Price LH: Family accommodation in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:441-443Link, Google Scholar

13. Magliano L, Tosini P, Guarneri M, Marasco C, Catapano F: Burden on the families of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a pilot study. Eur Psychiatry 1996; 11:192-197Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Black DW, Noyes R Jr: Comorbidity and obsessive-compulsive disorder, in Comorbidity of Mood and Anxiety Disorders. Edited by Maser JD, Cloninger CR. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990, pp 305-316Google Scholar

15. Angst J: Comorbidity of anxiety, phobia, compulsion and depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1993; 8:21-25Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Hanna GL: Demographic and clinical features of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:19-27Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Bolton D, Luckie M, Steinberg D: Long-term course of obsessive-compulsive disorder treated in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:1441-1450Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Koran, LM: Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders in Adults: A Comprehensive Clinical Guide. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 1999Google Scholar

19. Krieger N: Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health 1992; 92:703-710Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, Heninger GR, Charney DS: The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, I: development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:1006-1011Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. SAS/STAT User’s Guide, version 8. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 2000Google Scholar

22. Nelson E, Rice J: Stability of diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:826-831Link, Google Scholar

23. Helzer JE, Robins LN, McEvoy LT, Spitznagel EL, Stoltzman RK, Farmer A, Brockington IF: A comparison of clinical and diagnostic interview schedule diagnoses: physician reexamination of lay-interviewed cases in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:657-666Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Anthony JC, Folstein M, Romanoski AJ, Von Korff MR, Nestadt GR, Chahal R, Merchant A, Brown H, Shapiro S, Kramer M, Gruenberg EM: Comparison of the lay Diagnostic Interview Schedule and a standardized psychiatric diagnosis: experience in Eastern Baltimore. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:667-675Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Stein MB, Forde DR, Anderson G, Walker JR: Obsessive-compulsive disorder in the community: an epidemiologic survey with clinical reappraisal. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1120-1126Link, Google Scholar

26. Nestadt G, Samuels JF, Romanoski AJ, Folstein MF, McHugh PR: Obsessions and compulsions in the community. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 89:219-224Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Whitaker A, Johnson J, Shaffer D, Rapoport JL, Kalikow K, Walsh BT, Davies M, Braiman S, Dolinsky A: Uncommon troubles in young people: prevalence estimates of selected psychiatric disorders in a nonreferred adolescent population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:487-496Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Koran LM, Fireman B, Jacobson A, Leventhal JL: Adequacy of pharmacotherapy in an HMO: short- and long-term patterns. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2000; 57:1972-1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL: Clinical and epidemiological findings of significance to neuropharmacologic trials in OCD. Psychopharmacol Bull 1988; 24:466-470Medline, Google Scholar

30. Lensi P, Cassano GB, Correddu G, Ravagli S, Kunovac JL, Akiskal HS: Obsessive-compulsive disorder: familial-developmental history, symptomatology, comorbidity and course with special reference to gender-related differences. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 169:101-107Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Skoog G, Skoog I: A 40-year follow-up of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 55:121-127Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, Greenwald S, Hwu HG, Lee CK, Newman SC, Oakley-Browne MA, Rubio-Stipec M, Wickramaratne PJ, Wittchen H-U, Yeh E-K (Cross National Collaborative Group): The cross national epidemiology of obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55(suppl):5-10Google Scholar

33. Geller DA, Biederman J, Griffin S, Jones J, Lefkowitz TR: Comorbidity of juvenile obsessive-compulsive disorder with disruptive behavior disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:1637-1646Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Leckman JF, Grice DE, Barr LC, de Vries ALC, Martin C, Cohen DJ, McDougle CJ, Goodman WK, Rasmussen SA: Tic-related vs non-tic-related obsessive compulsive disorder. Anxiety 1995; 1:208-215Google Scholar