Clarifying the Relationship Between Unexplained Chronic Fatigue and Psychiatric Morbidity: Results From a Community Survey in Great Britain

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study examined the associations between several sociodemographic and psychosocial variables and unexplained chronic fatigue in the community before and after adjustment for psychiatric morbidity and determined the prevalence of fatigue and rate of disability resulting from fatigue in the general population. METHOD: The study is a secondary analysis of 1993 data from a household survey of psychiatric morbidity conducted by the Office for Population Censuses and Surveys in Great Britain. The survey included 12,730 subjects age 16–64 years. Unexplained chronic fatigue was used as the dependent variable in a logistic regression analysis, with various sociodemographic and psychosocial variables and psychiatric morbidity as the independent variables. Psychiatric morbidity was assessed by using the Revised Clinical Interview Schedule. Fatigue was measured by using the fatigue section of the Revised Clinical Interview Schedule. RESULTS: A total of 10,108 subjects agreed to cooperate (79.4% participation rate). The prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue was 9%. Subjects with psychiatric morbidity had higher rates of fatigue. Adjustment for psychiatric morbidity had a minor effect on the associations between sociodemographic factors and chronic fatigue. After adjustment, older subjects, women, and couples with children had higher rates of fatigue. Single subjects, widowed subjects, adults living with parents, and economically inactive subjects had lower rates of fatigue. Fatigue was associated with considerable disability, but most of this disability was explained by the association between fatigue and psychiatric morbidity. CONCLUSIONS: Unexplained chronic fatigue is a common condition, strongly associated with psychiatric morbidity. The close relationship between fatigue and psychiatric morbidity should not obscure the possibility of differences as well as similarities in their etiologies.

Chronic fatigue commonly refers to self-reported persistent and disabling fatigue lasting 6 months or longer (1). Chronic fatigue “unexplained” by current medical knowledge has been recently classified, according to internationally agreed-upon criteria, as either chronic fatigue syndrome or idiopathic chronic fatigue (2).

The relationship between unexplained chronic fatigue and psychiatric disorders is still a controversial issue despite the great research interest (2). Numerous studies have shown a strong association of unexplained chronic fatigue with general psychiatric morbidity and specific psychiatric disorders, mainly depression (3). This finding has been reported in studies done in tertiary centers (4), primary care settings (5, 6), and the community (7–9), and thus it is not due to selection bias (3). Several explanations have been suggested for this association (10, 11): 1) it could be due to overlapping criteria for chronic fatigue and psychiatric disorders, especially depression, 2) the association could be causal, i.e., fatigue could be viewed as a neurotic symptom and patients with unexplained chronic fatigue could suffer from a “primary” psychiatric disorder, 3) the psychiatric symptoms could be viewed as a secondary reaction to a chronic physical illness (reverse causality), and 4) confounding could occur if common factors contributed to the etiology of both psychiatric disorders and chronic fatigue.

The majority of the studies that have tried to clarify the relationship between unexplained chronic fatigue and psychiatric disorders have been conducted in tertiary care and have looked for clinical or laboratory differences between patients with chronic fatigue and subjects with psychiatric diagnoses or healthy comparison subjects (3). Although interesting results have been reported, what has become apparent is that the search for a single cause capable of explaining everything is bound to be unsuccessful (12). A few studies have been conducted in primary care settings (6, 10) in response to criticisms that the results of hospital-based studies suffer from serious methodological problems such as selection bias, referral bias, and unclear definitions of chronic fatigue (13). The findings of these studies showed that although chronic fatigue and psychiatric disorders overlap, they cannot be equated and may have different causes (3).

The goal of the study reported here is to extend the findings of this research by looking at the relationship between chronic fatigue and psychiatric morbidity in a community sample. This approach is free from the confounding effects of help-seeking behavior and differential access to health care, which are determined by cultural, social, and economic factors (14). So far, studies in the community have been concerned mainly with estimating the prevalence of chronic fatigue and its basic sociodemographic and psychiatric associations but have not tried to specifically address the complex relationship between fatigue and psychiatric morbidity (7–9, 15, 16). For this purpose, we used the data from a 1993 survey of psychiatric morbidity conducted by the Office for Population Censuses and Surveys in Great Britain (17). This general population survey gathered data on a large number of sociodemographic and psychosocial variables and measured psychiatric morbidity by using a structured interview. Our main aim was to examine associations between sociodemographic and psychosocial variables and unexplained chronic fatigue before and after the analysis adjusted for psychiatric morbidity. We hypothesized that if chronic fatigue was solely a symptom of the “neurotic spectrum,” then the observed associations would be explained by the presence of psychiatric morbidity. Additional aims were to examine the extent of disability associated with unexplained chronic fatigue and to estimate the prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue in a nationally representative sample of the general population in Great Britain.

Method

Data Set

The study reported here consisted of a secondary analysis of the data set from a household survey that was part of a survey of psychiatric morbidity conducted by the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys. The methods are described in detail in the original survey report (17). Briefly, a multistage stratified sampling procedure was used. From 12,730 adults eligible for interview (persons age 16–64 and living in private households), 10,108 agreed to cooperate, for a participation rate of 79.4%. The data used here were gathered between April 1993 and September 1993 by trained interviewers who personally interviewed each sampled adult in his/her home.

Survey Interview

The interviewers used a detailed questionnaire that included questions about sociodemographic characteristics, general health, life events, and social support. The published reports of the survey give details about the background and coding of the variables addressed in the questionnaire (17–19). In addition, all subjects were given the Revised Clinical Interview Schedule (20), a structured interview for measuring psychiatric morbidity that was designed to be used by lay interviewers. The reliability of the instrument was tested in primary care samples by Lewis et al. (20). In that test of reliability, which used a score of 12 as the threshold for identifying a case of psychiatric morbidity, the kappa between two successive interviews was 0.72 (95% confidence interval [CI]=0.65–0.79).

Measurement of Fatigue

Fatigue was measured by using the fatigue section of the Revised Clinical Interview Schedule. Scores (range=0–4) for this section relate to fatigue, feeling tired, or lacking energy in the week before the interview. A score of 1 was assigned for each of the following: 1) the symptom was present on 4 days or more, 2) the symptom was present for more than 3 hours in total on any day, 3) the subject had to push himself/herself to get things done on at least one occasion, and 4) the symptom was present at least once when the subject was doing things he/she used to enjoy. In our study, chronic fatigue was defined by a score of 2 or more (substantial fatigue) on the fatigue section of Revised Clinical Interview Schedule and a duration of 6 months or longer. We also noted instances of substantial fatigue that lasted longer than 2 weeks. Unexplained chronic fatigue was defined as chronic fatigue in subjects without a self-reported long-standing illness that could cause fatigue (any malignancy, any endocrine disorder, any heart disease, any respiratory disease, any infectious disease, any blood disorder, alcohol dependence, drug dependence, or psychosis [2, 21]). We did not exclude subjects with chronic renal failure, liver disease, and connective tissue disorders, because these disorders were grouped into broader categories in the original data set. We also did not exclude subjects with any neurological disorder, because this category included subjects who reported suffering from “myalgic encephalomyelitis,” a term commonly used in Great Britain to refer to unexplained chronic fatigue states.

Measurement of Psychiatric Morbidity

Current psychiatric morbidity was measured by using the total score on the Revised Clinical Interview Schedule. Because the score for fatigue is part of the total score for the Revised Clinical Interview Schedule, we excluded the fatigue section from the calculation of total scores, an approach used by other researchers (6). Thus, the range of possible scores in our study was 0–53 instead of 0–57, and subjects who scored 11 or more, instead of 12 or more, were classified as having psychiatric morbidity (20). We also calculated long-term Revised Clinical Interview Schedule scores to measure psychiatric morbidity within the past 6 months or longer.

Measurement of Disability and Use of Services

Disability was measured by considering the perceived level of health (poor, good) and the number of difficulties in activities of daily life. The latter variable was assessed by using a brief questionnaire, and the responses were classified by using two categories (difficulties in less than two activities of daily living or in two or more activities) (19). Use of services was estimated by asking the subjects whether they had consulted a general practitioner in the past 2 weeks for any reason, in the past 12 months for a physical reason, and in the past 12 months for a psychological reason (18).

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was carried out with the program Stata (22). Weighted percentages that take into account the age and sex distribution of the household population of Great Britain are presented (17). Odds ratios for chronic fatigue according to each variable were calculated by using logistic regression. Age was used as a continuous variable. When adjusting for Revised Clinical Interview Schedule scores, we also used a quadratic term because it significantly improved the fit of the model (likelihood ratio statistic=190.35, df=1, p<0.001). We also checked whether adjustment for both long-term and current psychiatric morbidity changed the associations between chronic fatigue and the sociodemographic and psychosocial variables. Since this adjustment produced no significant differences, we present the results after adjustment for current psychiatric morbidity. To take into account the clustered sampling of the original survey, the robust methods for variance estimation that are integrated into Stata were used (22).

Results

Prevalence of Fatigue

Overall, 22.5% (N=2,428, 95% CI=21.6%–23.3%) of the subjects complained of substantial fatigue lasting longer than 2 weeks. The prevalence of unexplained fatigue lasting longer than 2 weeks was 15.3% (N=1,630, 95% CI=14.6%–16.1%). The point prevalence of chronic fatigue (lasting longer than 6 months) was 13.4% (N=1,476, 95% CI=12.7%–14.1%). Excluding subjects with long-standing illnesses that can cause fatigue, the point prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue in our sample was 9.0% (N=970, 95% CI=8.5%–9.6%).

Sociodemographic and Psychosocial Variables and Unexplained Chronic Fatigue

Table 1 summarizes the odds ratios for chronic unexplained fatigue associated with each variable after adjusting for all other sociodemographic variables. Older people, women, couples with children, those with recent stressful life events, and those with perceived lack of social support had a higher prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue. Adults who were living with parents and single persons had a lower prevalence.

Psychiatric Morbidity and Unexplained Chronic Fatigue

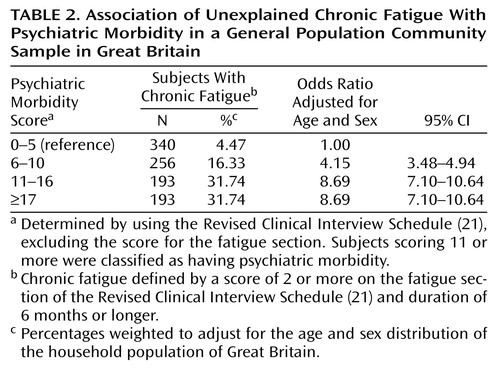

Psychiatric morbidity, as measured by the Revised Clinical Interview Schedule, was found to be strongly associated with unexplained chronic fatigue. Subjects with psychiatric morbidity had an increased prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue (odds ratio=4.93, 95% CI=4.23–5.75). To illustrate the association between psychiatric morbidity and chronic fatigue, the total Revised Clinical Interview Schedule scores were grouped into four categories. The prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue increased as the severity of psychiatric morbidity increased, even when the level of psychiatric morbidity was below the threshold for identifying a case of psychiatric morbidity (Table 2).

Sociodemographic and Psychosocial Correlates After Adjusting for Psychiatric Morbidity

Table 1 shows the odds ratios for chronic unexplained fatigue associated with each variable after adjusting both for all other sociodemographic variables and for psychiatric morbidity. With the exception of the association with stressful life events, all of the associations with unexplained chronic fatigue remained, although the odds ratios were usually lower than the odds ratios calculated without adjustment for psychiatric morbidity.

Functional Disability and Use of Services

Subjects with unexplained chronic fatigue were more likely to rate their health as poor, had more difficulty in carrying out activities of daily life, and consulted their general practitioner more often for a physical or emotional reason. Odds ratios for the association between these variables and chronic fatigue are presented in Table 3. However, after the analysis adjusted for psychiatric morbidity, only general practitioner consultations for a psychological reason remained significantly associated with fatigue.

Discussion

In a general population sample in Great Britain, we found that unexplained chronic fatigue had a point prevalence of 9%. Of primary interest was the finding that the associations between unexplained chronic fatigue and a number of sociodemographic and psychosocial factors were independent of its association with psychiatric morbidity. In addition, although unexplained chronic fatigue was associated with considerable disability and increased health care seeking, this pattern appeared to be due to the association between unexplained chronic fatigue and psychiatric disorder.

The findings should be considered in the context of some limitations. First, the study was a secondary analysis of a data set collected for other purposes. We measured fatigue by using the questions about this symptom included in the Revised Clinical Interview Schedule. This set of questions was not developed to be used as an independent scale for measuring fatigue, although the questions have been used by other researchers for comparison purposes in their development of a fatigue scale (23). Second, our approximation of the prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue relied on excluding subjects with self-reports of long-standing illness that can cause fatigue, and the reports may be inaccurate. We may have overestimated the prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue because we may have classified subjects with short-term illnesses that can cause fatigue as having unexplained chronic fatigue. Alternatively, we may have excluded subjects with unexplained chronic fatigue who are permanently sick because of their longstanding fatiguing illness. These misclassifications, if they were random, would not threaten the validity of our results; in the case of overascertainment, the misclassification would tend to reduce the measure of the association between fatigue and other factors, and in the case of underascertainment, it would leave the measure of the association unaffected (24). However, a systematic bias could also have been introduced.

Studies in many settings have found a strong association between psychiatric morbidity and chronic fatigue. The odds ratio of 4.9 (95% CI=4.2–5.7) that we found for this association is comparable with odds ratios found in other studies both in the community and in primary care settings (6, 7). Although the association of chronic fatigue with psychiatric morbidity appears very strong, we also found that various other factors are independently associated with chronic fatigue in the community. We studied a number of sociodemographic and psychosocial variables, and we found a higher prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue in older age groups, women, couples with children, and those with severe lack of social support. In contrast, the prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue was lower in single subjects, widowed subjects, adults living with their parents, and economically inactive subjects. Although the possibility of type I errors has to be considered, the pattern of results is not consistent with random error.

The prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue has not been systematically investigated in other community studies in the United Kingdom, although a few studies have reported that the point prevalence of chronic fatigue of any cause ranges from 14% to 18% (7, 8). In the United States, Walker et al. (9), using data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, reported that the 1-month prevalence of unexplained fatigue lasting longer than 2 weeks was 6%. Buchwald et al. (16), in a study of members of a single health maintenance organization, found a point prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue of 6.6%. These figures are quite similar to ours, given the different criteria and instruments used and the different populations studied.

Women were more likely to report unexplained chronic fatigue, even after the analysis adjusted for psychiatric morbidity. This finding is in line with findings in other community or primary care studies (8, 25), although the odds ratios we found are slightly higher. We also found that having no children, living with parents, and not working are associated with reduced rates of fatigue. These findings offer a perspective on the social circumstances that may influence the onset or maintenance of fatigue. Fewer responsibilities in everyday life may protect from chronic fatigue, and working harder and having more responsibilities may increase the risk for fatigue.

Unexplained chronic fatigue was associated with considerable disability. Subjects with fatigue had a worse perception of their health and were more likely to restrict their daily activities, compared with those without chronic fatigue. They also tended to visit a general practitioner more frequently. These findings confirm those of other studies in primary care settings (5, 25). However, our analysis suggested that the excess of disability was largely explained by psychiatric morbidity, because the association became nonsignificant after the analysis adjusted for psychiatric morbidity. These findings extend similar findings reported both in primary and tertiary care. Wessely et al. (25) reported a close association between functional impairment and psychiatric morbidity in subjects with chronic fatigue in a primary care setting. In a study in a tertiary care setting, Russo et al. (26) showed that improvement in psychological symptoms was associated with improvement in the functioning of chronic fatigue patients. This link between functional impairment and psychiatric morbidity was also noted in a World Health Organization study of psychological problems in primary care settings (27); that study used the ICD-10 diagnosis of neurasthenia, which is very similar to unexplained chronic fatigue. In contrast, Komaroff et al. (28), in their tertiary care study, reported that chronic fatigue syndrome patients with depression and those without depression had similar profiles of functional impairment, perhaps reflecting the highly selected study population. It is interesting to note that the association of psychological morbidity with disability and health care seeking is not specific to fatigue but has also been shown in other common conditions of functional origin, such as irritable bowel syndrome (29), headache (association with a history of panic disorder) (30), and tinnitus (association with affective disorder) (31).

How can one interpret these findings? Our analysis of a cross-sectional study is certainly limited in attempting to draw specific conclusions about etiology or the presence of specific risk factors. However, the purpose of our study was to compare the pattern of associations for unexplained chronic fatigue and psychiatric morbidity. Our results suggest that fatigue does have a different pattern of associations, once the association between fatigue and psychiatric morbidity has been taken into account. Thus, even if there is a causal relationship between psychiatric morbidity and fatigue, there are also other factors that are likely to be important.

Certain practical implications arise from our study. First, our findings support the view expressed by other researchers that a multifactorial model of fatigue states, which takes into account biological, psychological, and social factors, offers a better understanding of these complaints (32, 33). In practice, the assessment of fatigued patients should include not only symptoms, either physical or mental, but also beliefs, coping behaviors, and interpersonal and occupational problems, as has been proposed by Sharpe and his colleagues (34). Second, since disability is largely explained by the presence of psychiatric morbidity, the careful assessment and management of the latter could reduce the functional impairment of individual patients (35).

In conclusion, unexplained chronic fatigue is a common disabling condition in the general population and is strongly associated with psychiatric morbidity. However, the close relationship between fatigue and psychiatric morbidity should not obscure the possibility that there may be differences as well as similarities in their etiologies.

|

|

|

Received June 17, 1999; revision received Dec. 3, 1999; accepted Feb. 17, 2000. From the Division of Psychological Medicine, University of Wales College of Medicine; and the Social Survey Division, Office for National Statistics, London, UK. Address reprint requests to Dr. Skapinakis, Division of Psychological Medicine, Academic Unit, Monmouth House, University of Wales College of Medicine, Heath Park, Cardiff CF4 4XN, UK; [email protected] (e-mail). This work was begun while Dr. Skapinakis was studying for the master’s degree in public health at University of Wales College of Medicine. The authors thank Dr. Anthony David and Dr. Simon Wessely for comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

1. Wessely S: The epidemiology of chronic fatigue syndrome. Epidemiol Rev 1995; 17:139–151Medline, Google Scholar

2. Fukuda K, Straus S, Hickie I, Sharpe M, Dobbins J, Komaroff A: The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. Ann Intern Med 1994; 121:953–959Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome—Report of a Joint Working Group of the Royal Colleges of Physicians, Psychiatrists and General Practitioners. London, Gaskell (Royal College of Psychiatrists), 1996Google Scholar

4. Manu P, Matthews DA, Lane TJ: The mental health of patients with a chief complaint of chronic fatigue: a prospective evaluation and follow-up. Arch Intern Med 1988; 148:2213–2217Google Scholar

5. Kroenke K, Wood DR, Mangelsdorff D, Meier NJ, Powell JB: Chronic fatigue in primary care: prevalence, patients characteristics, and outcome. JAMA 1988; 260:929–934Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Wessely S, Chalder T, Hirsch S, Wallace P, Wright D: Psychological symptoms, somatic symptoms, and psychiatric disorder in chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome: a prospective study in the primary care setting. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1050–1059Google Scholar

7. Lawrie SM, Pelosi AJ: Chronic fatigue in the community: prevalence and associations. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:793–797Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Pawlikowska T, Chalder T, Hirsch SR, Wallace P, Wright DJM, Wessely S: Population based study of fatigue and psychological distress. Br Med J 1994; 308:763–766Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Walker EA, Katon WJ, Jemelka RP: Psychiatric disorders and medical care utilization among people in the general population who report fatigue. J Gen Intern Med 1993; 8:436–440Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Cope H, Mann A, Pelosi A, David A: Psychosocial risk factors for chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome following presumed viral illness: a case-control study. Psychol Med 1996; 26:1197–1209Google Scholar

11. Abbey SE, Garfinkel PE: Chronic fatigue syndrome and depression: cause, effect or covariate. Rev Infect Dis 1991; 13(suppl 1):S73–S83Google Scholar

12. Swartz MN: The chronic fatigue syndrome—one entity or many? N Engl J Med 1988; 319:1726–1728Google Scholar

13. David AS, Wessely S, Pelosi AJ: Postviral fatigue syndrome: time for a new approach. Br Med J 1988; 296:696–699Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Richman JA, Flaherty JA, Rospenda KM: Chronic fatigue syndrome: have flawed assumptions been derived from treatment-based studies? Am J Public Health 1994; 84:282–284Google Scholar

15. Price R, North CS, Wessely CS, Fraser VJ: Estimating the prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome and associated symptoms in the community. Public Health Rep 1992; 107:514–522Medline, Google Scholar

16. Buchwald D, Umali P, Umali J, Kith P, Pearlman T, Komaroff A: Chronic fatigue and the chronic fatigue syndrome: prevalence in a Pacific Northwest health care system. Ann Intern Med 1995; 123:81–88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Meltzer H, Gill B, Petticrew M, Hinds K: OPCS Surveys of Psychiatric Morbidity Report 1: The Prevalence of Psychiatric Morbidity Among Adults Living in Private Households. London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1995Google Scholar

18. Meltzer H, Gill B, Petticrew M, Hinds K: OPCS Surveys of Psychiatric Morbidity Report 2: Physical Complaints, Use of Services and Treatment of Adults With Psychiatric Disorders. London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1995Google Scholar

19. Meltzer H, Gill B, Petticrew M, Hinds K: OPCS Surveys of Psychiatric Morbidity Report 3: Economic Activity and Social Functioning of Adults With Psychiatric Disorders. London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1995Google Scholar

20. Lewis G, Pelosi AJ, Araya R, Dunn G: Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community: a standardized assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychol Med 1992; 22:465–486Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Komaroff AL: Clinical presentation and evaluation of fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome, in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Edited by Straus SE. New York, Marcel Dekker, 1994, pp 61–84Google Scholar

22. Stata Corporation: Stata Version 4.0. College Station, Tex.: Stata Corporation, 1995Google Scholar

23. Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, Watts L, Wessely S, Wright D, Wallace EP: Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res 1993; 37:147–153Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Rothman KJ, Greenland S: Precision and validity in epidemiologic studies, in Modern Epidemiology, 2nd ed. Edited by Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1998, pp 115–134Google Scholar

25. Wessely S, Chalder T, Hirsch S, Wallace P, Wright D: The prevalence and morbidity of chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome: a prospective primary care study. Am J Public Health 1997; 87:1449–1455Google Scholar

26. Russo J, Katon W, Clark M, Kith P, Sintay M, Buchwald D: Longitudinal changes associated with improvement in chronic fatigue patients. J Psychosom Res 1998; 45:67–76Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Ormel J, VonKorff M, Ustun TB, Pini S, Korten A, Oldehinkel T: Common mental disorders and disability across cultures: results from the WHO Collaborative Study on Psychological Problems in General Health Care. JAMA 1994; 272:1741–1748Google Scholar

28. Komaroff AL, Fagioli LR, Doolittle TH, Gandek B, Gleit MA, Guerriero RT, Kornish RJ, Ware NC, Ware JE, Bates DW: Health status in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and in general population and disease comparison groups. Am J Med 1996; 101:281–290Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Drossman DA, McKee DC, Sandler RS, Mitchell CM, Cramer EM, Lowman BC, Burger AL: Psychosocial factors in the irritable bowel syndrome: a multivariate study of patients and nonpatients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 1988; 95:701–708Medline, Google Scholar

30. Stewart WF, Shechter A, Liberman J: Physician consultation for headache pain and history of panic: results from a population-based study. Am J Med 1992; 92:(suppl 1A)35S–40SGoogle Scholar

31. Sullivan MD, Katon W, Dobie R, Sakai C, Russo J, Harrop-Griffiths J: Disabling tinnitus: association with affective disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1988; 10:285–291Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Sharpe M: Chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996; 19:549–573Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Lewis G, Wessely S: The epidemiology of fatigue: more questions than answers. J Epidemiol Community Health 1992; 46:92–97Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Sharpe M, Chalder T, Palmer I, Wessely S: Chronic fatigue syndrome: a practical guide to assessment and management. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1997; 19:185–199Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Ormel J, VonKorff M, van den Brink W, Katon W, Brilman E, Oldehinkel T: Depression, anxiety, and social disability show synchrony of change in primary care patients. Am J Public Health 1993; 83:385–390Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar