Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of the Use of Lithium to Augment Antidepressant Medication in Continuation Treatment of Unipolar Major Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Use of lithium to augment antidepressant medication has been shown to be beneficial in the acute treatment of depression. The authors examined the efficacy of lithium augmentation in the continuation treatment of unipolar major depressive disorder. METHOD: Thirty patients with a refractory major depressive episode who had responded to acute lithium augmentation during an open 6-week study participated in a randomized, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of lithium augmentation during continuation treatment. After a 2–4-week stabilization period following remission, patients were randomly assigned to receive either lithium or placebo for a 4-month period. Antidepressant medication was continued throughout the study. RESULTS: Relapses (including one suicide) occurred in seven (47%) of the 15 patients who received placebo in addition to antidepressants. None (0%) of the 14 patients who received lithium augmentation with antidepressants suffered a relapse during the double-blind phase of the study. Five of the seven relapsing patients in the placebo group developed a depressive episode, and the other two experienced a manic episode. CONCLUSIONS: Lithium augmentation in the continuation phase of treatment of unipolar major depressive disorder effectively protects patients against a relapse. Patients who respond to lithium augmentation should be maintained on lithium augmentation for a minimum of 6 months or even longer.

True resistance to antidepressant therapy is one of the challenging issues in the treatment of depressive disorders (1, 2). Among the strategies for the treatment of refractory depression, the use of lithium to augment antidepressant medication has increased rapidly since the first description of this protocol in an open study (3). Lithium has been found to potentiate the therapeutic effects of a broad spectrum of antidepressants including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (4, 5). The combination of lithium with antidepressants has not been reported to be associated with serious side effects (6, 7), and therefore it has been recommended as a first-line approach for patients with treatment-resistant depression (8–10). In contrast to most other potential treatment strategies in refractory depression, lithium augmentation has been repeatedly investigated in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (5, 11–19). Although some of the earlier placebo-controlled trials found no benefit of lithium augmentation (13, 14, 16), recent larger studies that have used thorough methods have shown a clear benefit of lithium compared to the placebo (5, 17, 19). A recent meta-analysis that included nine double-blind, placebo-controlled trials also provided firm evidence that lithium augmentation has a statistically significant effect on response rate compared to placebo (20). A pooled odds ratio of 3.31 for response with lithium augmentation compared to response with placebo was found for the trials that used a minimum dose of 800 mg/day of lithium carbonate or a dose sufficient to obtain serum lithium levels of ≥0.5 meq/liter and had a minimum treatment duration of 2 weeks.

The scientific evidence for the efficacy of this treatment strategy is unambiguous, yet a deficit exists in our knowledge about the optimal duration of lithium augmentation. To our knowledge, the efficacy of lithium augmentation has been studied prospectively only in the acute treatment of depression. Published open and controlled studies have focused on acute symptoms and on periods of lithium use ranging between 2 days and 6 weeks (8, 20). Follow-up data are not presented in any of the prospective studies. Only one retrospective study with a naturalistic design has described the global outcome of patients with therapy-resistant depression who were treated with lithium augmentation (21). Therefore, it is unknown how long lithium augmentation should be continued in responders to prevent early relapse of depression. Continuation treatment of a depressive episode is defined as the continued administration of a drug over 4–6 months after control of acute symptoms for the purpose of maintaining control over the episode (22, 23).

The primary goal of this study was to investigate the efficacy of lithium augmentation in the continuation treatment of major depression.

Method

This study was conducted at the Department of Psychiatry, Freie Universität Berlin, an academic medical center, and included inpatients and outpatients from the clinical programs. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Subjects

Patients of both sexes, age 18 years or older, with a major depressive episode (referred to as the index episode) were entered in the study. To be eligible for the acute treatment phase of the study, a patient had to satisfy the following criteria: 1) a current major depressive episode that met DSM-III-R criteria, 2) a score of at least 15 points on the 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (24), 3) a score of 4 (“moderately ill”) or more on the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale for severity of illness (25), 4) no acute suicidal ideation, 5) failure to respond to an adequate trial of either a nonselective antidepressant or an SSRI (criteria for an adequate trial are given later), 6) not more than four lifetime depressive episodes and not more than two depressive episodes in the 5 years before the index episode, 7) no history of hypomanic or manic episode, 8) no other DSM-III-R axis I diagnosis, and 9) no medical exclusions for any condition incompatible with lithium therapy. To be eligible for the continuation treatment phase, patients had to satisfy criteria for remission during a 6-week period after initiation of lithium augmentation.

Diagnoses were verified by using a checklist for DSM-III-R criteria for major depressive disorder. Consensus diagnoses were made at a conference of the supervising psychiatrist and the research psychiatrist by using additional information about the patient from a semistructured diagnostic interview, including demographic characteristics, psychiatric history, and the results of a physical examination, a urine screen for illegal drugs, and routine laboratory tests.

Study Design and Procedures

Before inclusion in the study, all patients were treated for their depressive episode by using a standardized stepwise drug treatment regimen developed for the treatment of hospitalized patients with a depressive syndrome at the Department of Psychiatry, Freie Universität Berlin, in 1990 (26, 27). The standardized stepwise drug treatment regimen is a treatment algorithm for clinical settings that consists of a series of different medication steps that are based on clinical evaluations made every 2 weeks with an established psychiatric rating scale for depression. A patient who does not respond to treatment at a given step enters the next step. Partial responders do not switch to the next step, but they do not remain in the same step for longer than 4 weeks. Briefly, as used in this study, the protocol began with a 1-week drug-free washout period, during which the patient was evaluated to establish a diagnosis and determine the severity of depression (step 1). In step 2, the patient was given either a tricyclic or tetracyclic (150 mg/day), an SSRI (paroxetine, 20 mg/day), or trazodone or venlafaxine (150 mg/day) for ≥2 weeks. (The choice of medication is not determined by the protocol.) In step 3, the dose was increased to 300 mg/day for tricyclics or tetracyclics, to 40 mg/day for paroxetine, and to 300 mg/day for trazodone or venlafaxine, if the increase was tolerated by the patient. The duration of treatment in step 3 was ≥2 weeks. In step 4, lithium was added to the antidepressant to achieve lithium blood levels of 0.5–1.0 mmol/liter.

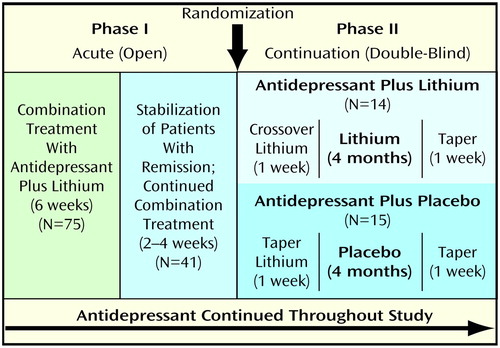

Patients who did not respond during step 3 of the standardized stepwise drug treatment regimen protocol were entered in the study, which consisted of two phases: I) an open, acute treatment phase in which all patients received lithium augmentation, and II) a placebo-controlled continuation phase. An overview of the study design is given in Figure 1.

Phase I (acute treatment phase)

The purpose of this open 6-week lithium augmentation phase was to control acute symptoms and to resolve the index episode. The 75 subjects who participated in this phase had failed to respond to an antidepressant trial (step 3 of the standardized stepwise drug treatment regimen). The mean duration of antidepressant treatment before lithium augmentation was 46.1 days (SD=29.7). Subjects continued to receive the same antidepressant throughout the 6-week acute treatment phase (dose reductions of 20% or less were allowed only if side effects occurred) and received either lithium carbonate or lithium sulfate at an initial dose of 450 mg/day (carbonate) or 660 mg/day (sulfate). Lithium carbonate was increased to 675–900 mg/day, lithium sulfate to 990–1320 mg/day for days 3–7, depending on individual tolerability. Serum lithium levels were obtained after 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks. The depression of 41 (55%) of the 75 patients remitted during the 6-week open lithium augmentation phase. After remission, patients continued to take their medication for another 2–4 weeks, depending on clinical judgment of stability.

Phase II (continuation treatment phase)

Eleven patients who responded to lithium augmentation declined or were not eligible to participate in the placebo-controlled continuation treatment phase for various reasons (e.g., fear of relapse during placebo treatment, unwilling to drive the long distance necessary to attend follow-up visits, relocation to another city, unwilling to participate in a research study). The remaining 30 patients who gave informed consent to enter the controlled study were taking the following antidepressants: amitriptyline, N=16, clomipramine, N=4, nortriptyline, N=3, dibenzepin, N=2, imipramine or maprotiline, each N=1 (mean dose of tricyclics or tetracyclics during lithium augmentation: 224.0 mg/day, SD=93.3), and trazodone (dose=250 mg/day), paroxetine (dose=40 mg/day), or venlafaxine (dose=150 mg/day), each N=1. Before double-blind treatment, patients’ remission was again verified by clinical evaluation. Patients were then randomly assigned to receive either lithium or placebo under double-blind conditions for another 4 months. Randomization was performed in blocks of 10 subjects. Antidepressant medication was continued throughout the study. There was no statistically significant difference in the distribution of the antidepressants between groups during the continuation phase (lithium group: amitriptyline, N=9, clomipramine, N=3, and nortriptyline, trazodone, or paroxetine, each N=1; placebo group: amitriptyline, N=7, nortriptyline or dibenzepin, each N=2, and clomipramine, imipramine, maprotiline, or venlafaxine, each N=1). There were no significant differences in the doses or blood levels of tricyclics or tetracyclics between groups during the continuation phase. Subjects who were randomly assigned to the placebo group were withdrawn from lithium within a 1-week period. Subjects who were randomly assigned to the lithium group were switched from lithium carbonate to lithium sulfate or vice versa, on the assumption that the different lithium tablets might have a slightly different taste than the placebo tablets. All subjects were informed that they would receive a different tablet.

We intended that patients would have 12-hour postdose serum lithium levels of 0.5–1.0 mmol/liter throughout the study (phase I and phase II). Lithium levels from patients’ laboratory tests were reported to only the psychiatrist who dispensed the medication and recommended dose adjustments. To guarantee blinded conditions, the psychiatrist who dispensed the medication communicated patients’ serum lithium levels to the treating psychiatrists. Actual serum lithium levels were reported for patients in the lithium group. For the placebo-treated patients, fictional serum lithium levels between 0.3 and 1.2 mmol/liter were reported.

Subjects were seen by a treating psychiatrist on a weekly basis for the first 2 months of double-blind treatment and biweekly thereafter at the Berlin Lithium Clinic, a specialized outpatient clinic for the long-term treatment of patients with affective disorders. At the clinic visits, patients’ laboratory measures, including serum lithium level, thyroid function, and creatinine level, were obtained, and patients were assessed with the following psychiatric rating scales: the 21-item version of the Hamilton depression scale, the CGI for severity of illness and global improvement, German version (28) (CGI severity scale range=1–8, CGI improvement scale range=1–8), and the Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale (29). The study was terminated by tapering the study medication (lithium or placebo) over a 1-week period while the antidepressant was continued at the same dose (Figure 1).

Outcome Criteria

Operationalized definitions of remission and relapse were used (30). By definition, acute symptoms were controlled (remission) when the patient 1) achieved rating scores on the Hamilton depression scale of 10 or lower on two consecutive visits within a 7-day period, 2) achieved a score of 3 (“borderline mentally ill”) or less on the CGI severity scale and a score of 3 (“much improved”) or 2 (“very much improved”) on the CGI improvement scale, and 3) was judged by two independent senior or supervising psychiatrists as asymptomatic (i.e., the patient no longer met syndromal criteria for the disorder and had no more than minimal symptoms). Treatment outcome during the double-blind phase was defined primarily in terms of the occurrence of a relapse. In case of a relapse, the subject discontinued participation in the study protocol (dropped out). A subject who was doing worse when he or she came for a clinic visit was observed by one of the blinded investigators. If the subject was judged to be suffering a relapse, the subject was then seen by the supervising psychiatrist of the Lithium Clinic and by a senior psychiatrist of the Department of Psychiatry, both of whom had no knowledge of whether the subject was assigned to the lithium group or the placebo group. A relapse was confirmed if the assessment made by using the rating scales and the clinical evaluation of both the supervising psychiatrist and the senior psychiatrist indicated a major depressive episode. A relapse was defined as a depressive syndrome that satisfied the operationalized diagnostic and severity criteria for admission to the study. A manic relapse was defined as a manic syndrome that satisfied the following criteria: 1) a current manic episode according to DSM-III-R criteria and 2) a score of 15 or more on the Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale. Treatment for patients who relapsed was determined by the treating psychiatrist. However, we intended that subjects who relapsed would be returned to lithium augmentation, which they had received during the acute treatment phase of the study.

Statistical Analysis

The relapse rates of subjects in the two study groups during the double-blind evaluation period were compared by using Fisher’s exact test. To further identify clinical and demographic variables that had a possible effect on clinical outcome, a logistic regression analysis with the stepwise selection method (31) was performed. The following clinical and demographic variables were included in the logistic regression analysis as predictors: age, sex, number of previous episodes, duration of current episode, treatment (lithium/placebo), lithium serum level before randomization, and Hamilton depression scale score before lithium augmentation and at remission. To examine whether clinical or demographic variables differed between the active drug and the placebo group, the variables predicting clinical outcome were compared by using Fisher’s exact test or the Mann-Whitney U test. All statistical tests were two-tailed. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

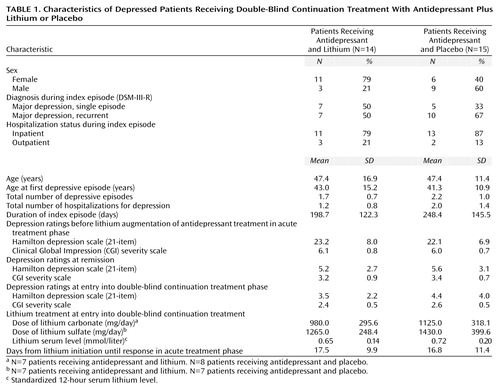

Thirty patients (18 women and 12 men) with a major depressive episode (13 single episode, 17 recurrent; 25 inpatients, five outpatients) who had responded to treatment with the addition of lithium to ongoing antidepressant medication participated in the study. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study group are shown in Table 1. One patient withdrew her consent to participate in the study shortly after randomization (23 days). Therefore, 29 patients completed the protocol and were eligible for the statistical analyses.

Relapse occurred in seven (47%) of the 15 patients who received antidepressants plus placebo. None (0%) of the 14 patients who continued to receive lithium-antidepressant combination treatment suffered a relapse. The relapses occurred an average of 27 days (SD=35, range=7–103) after beginning double-blind treatment. Fisher’s exact test revealed a significant group difference in the relapse rate (p=0.006). Of the seven relapses in the placebo group, five were depressive relapses and two were manic relapses. The two patients with a manic relapse had never before experienced a manic episode, and both patients subsequently received a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Therefore, we conducted a separate analysis that included only the patients with unipolar depression (N=27). This analysis also revealed a significant difference in the relapse rate of the two treatment groups (p=0.02, Fisher’s exact test). Patients with a depressive relapse had a mean Hamilton depression scale score of 20.0 (SD=4.1) and a mean CGI severity score of 5.8 (SD=0.4) at the time the relapse was confirmed. Two patients were rehospitalized, two patients who had been followed in a day program after discharge from the hospital were readmitted to the hospital, and one patient committed suicide.

The two groups of subjects did not differ significantly in demographic and clinical variables or in rating scores before lithium augmentation, at remission, and at entry into double-blind treatment (Table 1). The logistic regression analysis that examined whether the outcome variance could be explained by demographic and clinical variables identified three significant predictors of clinical outcome: treatment, sex, and Hamilton depression scale score before lithium augmentation. Clinical outcome was predicted correctly in 96.6% of the patients when these three variables were included in the regression model (Table 2). The rate of correct classification of patients was 100% for patients with a relapse (sensitivity) and 95.5% for patients without a relapse (specificity).

With treatment as the only variable in the logistic regression analysis, 22 patients without a relapse were classified correctly. With the addition of the Hamilton depression scale score before lithium augmentation, 21 patients without a relapse and five patients with a relapse were classified correctly. With the inclusion of sex, the logistic regression analysis correctly predicted the classification of 21 patients without a relapse and seven patients with a relapse. The mean Hamilton depression scale score before lithium augmentation was 26.4 (SD=7.5) for patients with a relapse and 21.5 (SD=7.0) for patients without a relapse. There were three male and four female subjects in the relapse group and nine male and 13 female subjects in the nonrelapse group.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first controlled evaluation of the efficacy of lithium augmentation in the continuation phase of treatment of major depression. The most important result of this study is that active lithium augmentation during the continuation treatment phase provided effective prevention against relapse into depression. Lithium was significantly more effective than placebo in preventing relapse for patients with major depression who had responded to lithium augmentation in the acute treatment phase. Substitution of placebo for lithium medication resulted in a rapid return of severe symptoms in a significant number of patients who were euthymic during the week lithium was withdrawn. One-third of the patients suffered a depressive relapse after they had entered the placebo phase of the study, but none of the patients who were randomly assigned to receive active lithium medication did so. The results clearly indicate that lithium therapy in patients who respond to lithium augmentation should be continued longer than a stabilization period of 2–4 weeks to prevent early relapse.

Results of this study also support the hypothesis that lithium augmentation is effective in the control of acute depressive symptoms. The remission rate (55%) associated with open lithium augmentation in this study was consistent with rates reported in the majority of other studies in the literature (7, 8). As in these other studies, we found that the mean length of time to remission of patients receiving lithium augmentation is approximately 2 weeks.

Outcome and treatment after relapse were monitored closely. Patients with a depressive relapse immediately received adjunctive lithium in an open fashion. Four of them had a favorable outcome to reinstitution of lithium augmentation, and their depression fully remitted in a 2-week period. However, in the case of one patient, reinstitution of lithium augmentation did not resolve the depressive relapse. After 6 days of open lithium treatment, the patient’s serum lithium level was 0.59 mmol/liter. Because the patient’s depressive symptoms seemed to decrease, the treating psychiatrist decided not to hospitalize the patient. Eleven days after restoration of lithium augmentation, the patient unfortunately committed suicide.

Of the 29 patients who recovered from their index episode of major depressive disorder during the open lithium augmentation trial and went on to participate in the double-blind continuation phase, two (7%) relapsed into another type of DSM-III-R affective episode (bipolar disorder, manic) during the double-blind phase. A change of diagnosis over time in about 10%–20% of patients with unipolar depression has been described repeatedly in the literature (32–34).

The higher percentage of depressive relapses with placebo than with the active drug was in line with rates reported in studies that have examined the efficacy of antidepressant monotherapy during the continuation phase of treatment (35–38). As reviewed by Prien (22), relapse rates in placebo-controlled continuation therapy trials ranged from 31% to 80% for patients who received placebo, compared with only 0%–31% for patients who received active medication.

The design of this study had some limitations that could confound interpretation of the data. First, the 1-week duration of lithium withdrawal was relatively short. There is a controversy in the literature about the existence of a rebound phenomenon caused by rapid withdrawal of lithium. Some patients, previously well maintained on long-term lithium treatment, have been reported to experience affective relapses shortly (5 days to 6 weeks) after lithium is discontinued (39–41). However, data from other groups do not support the existence of a rebound phenomenon (42, 43). The patients in the study reported here were treated with lithium only for a relatively short period during an acute episode, and lithium was not abruptly withdrawn but was relatively gradually withdrawn. Therefore, we suggest that the relapses seen in this study could be accounted for by a rapid reoccurrence of depressive symptoms that had been suppressed by effective combined medication rather than by a rebound effect due to a rapid withdrawal of lithium. Second, the size of the study group was relatively small. Therefore, the results of the logistic regression analysis should be interpreted with some caution. However, because all depressive relapses and the suicide occurred in the same randomization group, we felt that it would have been unethical to repeat the study to achieve a larger study group. Third, the study could not address whether the benefit of lithium during the continuation phase was due to augmentation or to lithium alone. A larger study group might have allowed a third arm in which antidepressants were tapered and stopped at entry into the double-blind phase so that the effect of continuation therapy with lithium monotherapy could also be evaluated.

Continuation treatment trials in depression have shown that optimal treatment of an episode of depression includes continuation of an effective medication regimen for 4–5 months after remission (44). The results of this study confirm this recommendation also for the combined treatment of an antidepressant plus lithium in patients who respond to lithium augmentation. However, in the light of the dramatic drug/placebo difference observed in this study, a longer period than 6 months (up to 12 months or even longer) for continuation treatment of effective lithium augmentation may be appropriate. In conclusion, the frequency and the severity of some of the depressive relapses (including one suicide) in placebo-treated patients in this study clearly show that lithium augmentation is an effective procedure to control depressive symptoms in the acute and continuation phases of depressive episodes.

|

|

Presented in part at the World Congress of Psychiatry, Hamburg, Germany, Aug. 6–11, 1999, and at the annual meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, Acapulco, Mexico, Dec. 12–16, 1999 Received Sept. 3, 1999; revision received Feb. 2, 2000; accepted Mar. 9, 2000.From the Department of Psychiatry, Universitätsklinikum Benjamin Franklin, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin; the Neuropsychiatric Institute & Hospital, Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California at Los Angeles; and the Max-Planck Institute of Psychiatry, Munich. Address reprint requests to Dr. Bauer, Neuropsychiatric Institute & Hospital, Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California at Los Angeles, 300 UCLA Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095-6968; [email protected] (e-mail). The authors thank H. Helmchen, M.D., and F. Boegner, M.D., for their support in the initial phase of the study, P. Grof, M.D., for comments on the manuscript, and A. Yassouridis, Ph.D., for advice on statistics. Lithium and placebo tablets were provided by SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals, Munich.

Figure 1. Phases of a Study on the Effectiveness of Lithium Augmentation of Antidepressant Medication in the Continuation Treatment of Depressed Patientsa

aMean period of treatment with antidepressants before phase I addition of lithium was 461 days (SD=29.7). Eleven of the 41 patients who experienced remission declined to participate in the continuation phase, and one additional patient dropped out before the end of the study.

1. Nierenberg AA, Amsterdam JD: Treatment-resistant depression: definition and treatment approaches. J Clin Psychiatry 1990; 51(suppl 6):39–47Google Scholar

2. Guscott R, Grof P: The clinical meaning of refractory depression: a review for the clinician. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:695–704Link, Google Scholar

3. Montigny de C, Grunberg F, Mayer A, Deschenes JP: Lithium induces rapid relief of depression in tricyclic antidepressant drug non-responders. Br J Psychiatry 1981; 138:252–256Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Bauer M: The combined use of lithium and SSRIs. J Serotonin Res 1995; 2:69–76Google Scholar

5. Baumann P, Nil R, Souche A, Montaldi S, Baettig D, Lambert S, Uehlinger C, Kasas A, Amey M, Jonzier-Perey M: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of citalopram with and without lithium in the treatment of therapy-resistant depressive patients: a clinical, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacogenetic investigation. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996; 16:307–314Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Nelson JC: Combined treatment strategies in psychiatry. J Clin Psychiatry 1993; 54(suppl 9):42–49Google Scholar

7. Rouillon F, Gorwood P: The use of lithium to augment antidepressant medication. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 5):32–39Google Scholar

8. Montigny de C: Lithium addition in refractory depression, in Refractory Depression: Current Strategies and Future Directions. Edited by Nolen WA, Zohar J, Roose SP, Amsterdam JD. London, John Wiley & Sons, 1994, pp 47–57Google Scholar

9. Nemeroff CB: Augmentation strategies in patients with refractory depression. Depress Anxiety 1996–97; 4:169–181Google Scholar

10. Shelton RC: Treatment options for refractory depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60(suppl 4):57–61Google Scholar

11. Heninger GR, Charney DS, Sternberg DE: Lithium carbonate augmentation of antidepressant treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:1335–1342Google Scholar

12. Cournoyer G, de Montigny C, Ouellete J, Leblanc G, Langlois R, Elie R: Lithium addition in tricyclic-resistant unipolar depression: a placebo-controlled study, in Abstracts of Collegium Internationale Neuro-Psychopharmacologicum, Florence, Italy, June 19–23, 1984. Nashville, Tenn, ACNP, p 179Google Scholar

13. Kantor D, McNevin S, Leichner P, Harper D, Krenn M: The benefit of lithium carbonate adjunct in refractory depression—fact or fiction? Can J Psychiatry 1986; 31:416–418Google Scholar

14. Zusky PM, Biederman J, Rosenbaum JF, Manschreck TC, Gross CC, Weilberg JB, Gastfriend DR: Adjunct low dose lithium carbonate in treatment-resistant depression: a placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1988; 8:120–124Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Schöpf J, Baumann P, Lemarchand T, Rey M: Treatment of endogenous depressions resistant to tricyclic antidepressants or related drugs by lithium addition: results of a placebo-controlled double-blind study. Pharmacopsychiatry 1989; 22:183–187Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Browne M, Lapierre YD, Hrdina PD, Horn E: Lithium as an adjunct in the treatment of major depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1990; 5:103–110Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Joffe RT, Singer W, Levitt AJ, MacDonald C: A placebo-controlled comparison of lithium and triiodothyronine augmentation of tricyclic antidepressants in unipolar refractory depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:387–393Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Stein G, Bernadt M: Lithium augmentation therapy in tricyclic-resistant depression: a controlled trial using lithium in low and normal doses. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 162:634–640Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Katona CLE, Abou-Saleh MT, Harrison DA, Nairac BA, Edwards DRL, Lock T, Burns RA, Robertson MM: Placebo-controlled trial of lithium augmentation of fluoxetine and lofepramine. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:80–86Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Bauer M, Döpfmer S: Lithium augmentation in treatment-resistant depression: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1999; 19:427–434Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Nierenberg AA, Price LH, Charney DS, Heninger GR: After lithium augmentation: a retrospective follow-up of patients with antidepressant-refractory depression. J Affect Disord 1990; 18:167–175Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Prien RF: Efficacy of continuation drug therapy of depression and anxiety: issues and methodologies. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1990; 10(suppl 3):86S–90SGoogle Scholar

23. Thase ME, Kupfer DJ: Recent developments in the pharmacotherapy of mood disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996; 64(suppl 4):646–659Google Scholar

24. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 218–222Google Scholar

26. Helmchen H: Current trends of research on antidepressive treatment and prophylaxis. Compr Psychiatry 1979; 20:201–214Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Linden M, Helmchen H, Mackert A, Müller-Oerlinghausen B: Structure and feasibility of a standardized stepwise drug treatment regimen (SSTR) for depressed inpatients. Pharmacopsychiatry 1994; 27(suppl 1):51–53Google Scholar

28. Association for Methodology and Documentation in Psychiatry (AMDP) and Collegium Internationale Psychiatriae Scalarum (CIPS) (eds): Rating Scales for Psychiatry, European ed. Weinheim, Germany, Beltz-Test Verlag, 1990Google Scholar

29. Bech P, Bolwig TG, Kramp P, Rafaelsen OJ: The Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale and the Hamilton Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1979; 59:420–430Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, Keller MB, Kupfer DJ, Lavori PW, Rush AJ, Weissman MM: Conceptualization and rational for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:851–855Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Applied Logistic Regression. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1989Google Scholar

32. Angst J, Felder W, Frey R, Stassen HH: The course of affective disorders, I: change of diagnosis of monopolar, unipolar, and bipolar illness. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr 1978; 226:57–64Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Shapiro RW, Keller MB: Initial 6-month follow-up of patients with major depressive disorder: a preliminary report from the NIMH collaborative study of the psychobiology of depression. J Affect Disord 1981; 3:205–220Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Shea MT, Warshaw M, Maser JD, Coryell W, Endicott J: Recovery from major depression: a 10-year prospective follow-up across multiple episodes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:1001–1006Google Scholar

35. Mindham RH, Howland C, Shepherd M: An evaluation of continuation therapy with tricyclic antidepressants in depressive illness. Psychol Med 1973; 3:5–17Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Coppen A, Ghose K, Montgomery S, Rama Rao VA, Bailey J, Jorgensen A: Continuation therapy with amitriptyline in depression. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:28–33Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Glen AI, Johnson AL, Shepherd M: Continuation therapy with lithium and amitriptyline in unipolar depressive illness: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Psychol Med 1984; 14:37–50Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Prien RF, Kupfer DJ: Continuation drug therapy for major depressive episodes: how long should it be maintained? Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:18–23Google Scholar

39. Small JB, Small IF, Moore DF: Experimental withdrawal of lithium in recovered manic-depressive patients: a report of five patients. Am J Psychiatry 1971; 127:1555–1559Google Scholar

40. Lapierre YD, Gagnon A, Kokkinidis L: Rapid recurrence of mania following lithium withdrawal. Biol Psychiatry 1980; 15:859–864Medline, Google Scholar

41. Christodoulou GN, Lykouras EP: Abrupt lithium discontinuation in manic-depressive patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1982; 65:310–314Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Sashidharan SP, McGuire RJ: Recurrence of affective illness after withdrawal of long-term lithium treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 68:126–133Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Schou M: Has the time come to abandon prophylactic lithium treatment? a review for clinicians. Pharmacopsychiatry 1998; 31:210–215Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Kupfer DJ: Management of recurrent depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1993; 54(Feb suppl):29–33Google Scholar