Adolescent Personality Disorders Associated With Violence and Criminal Behavior During Adolescence and Early Adulthood

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: A community-based, longitudinal prospective study was conducted to investigate whether personality disorders during adolescence are associated with elevated risk for violent behavior during adolescence and early adulthood. METHOD: A community-based sample of 717 youths from upstate New York and their mothers were interviewed in 1983, 1985–1986, and 1991–1993. Axis I and II disorders were assessed in 1983 and 1985–1986. Antisocial personality disorder was not assessed because most participants were less than 18 years of age in 1983 and 1985–1986. Violent behavior was assessed in 1985–1986 and 1991–1993. RESULTS: Adolescents with a greater number of DSM-IV cluster A or cluster B personality disorder symptoms were more likely than other adolescents in the community to commit violent acts during adolescence and early adulthood, including arson, assault, breaking and entering, initiating physical fights, robbery, and threats to injure others. These associations remained significant after controlling for the youths’ age and sex, for parental psychopathology and socioeconomic status, and for co-occurring psychiatric disorders during adolescence. Paranoid, narcissistic, and passive-aggressive personality disorder symptoms during adolescence were independently associated with risk for violent acts and criminal behavior during adolescence and early adulthood after the covariates were controlled. CONCLUSIONS: Cluster A and cluster B personality disorders and paranoid, narcissistic, and passive-aggressive personality disorder symptoms during adolescence may increase risk for violent behavior that persists into early adulthood.

Research investigating the association between psychiatric disorders and violent behavior among adolescents promises to increase our understanding of the role that psychiatric disorders play in the development of violent behavior during adolescence. Increased understanding of this association may facilitate efforts to prevent the occurrence of extreme acts of violence among young people. Previous studies in this field have focused predominantly on the association between disruptive behavior disorders and violent or criminal acts. Despite research indicating that personality disorders are associated with increased risk for violent behavior among adults (1–10), little is currently known about the association between adolescent personality disorders and violent behavior during adolescence and early adulthood. The association between personality disorders and violent acts is of particular interest because personality disorders tend to be characterized by difficulties in interpersonal relationships, including interpersonal conflict (11, 12), which may play a significant role in the development of violent behavior during adolescence.

Previous research has indicated that personality disorders are often associated with violent behavior in adult clinical and forensic populations (4–10, 13, 14). These studies have increased our understanding of the association between personality disorders and violence among adults who are in the criminal justice system or receiving psychiatric treatment. However, most of these studies have important methodological limitations, such as the use of small sample sizes or failure to control for the presence of co-occurring psychiatric disorders. In addition, these findings may not generalize to the overall adult population. Only community-based longitudinal research can permit researchers to determine whether personality disorders are independently associated with violent behavior among individuals in the general population. To date, few community-based studies have investigated associations between personality disorders and violent behavior. Cross-sectional studies have suggested that antisocial (2, 3, 15, 16), avoidant (2), borderline (2, 3), histrionic (2), narcissistic (2), paranoid (1, 2), passive-aggressive (1, 2), and schizotypal (2) personality disorders may be associated with violent behavior among adults in the community. However, these studies have had important methodological limitations, including the use of small or unrepresentative samples (1, 2), limitations in the assessment of violent behavior (1, 2), assessment of only antisocial personality disorder (15, 16), or failure to control for co-occurring psychiatric disorders (2). Furthermore, since these studies were all cross-sectional, it was not possible to ascertain whether personality disorders were associated with increased risk for violent behavior.

To our knowledge, no previous investigation has examined the association between personality disorders and violent behavior among adolescents in the community, and no previous community-based study has used longitudinal prospective data to investigate whether specific personality disorders are associated with increased risk for violent behavior among adolescents or adults. We examined data from the Children in the Community Study (17)—a community-based, longitudinal prospective study—to investigate whether personality disorders during adolescence were associated with violent acts during adolescence and early adulthood. Statistical procedures were used to control for the youths’ age and sex, co-occurring axis I and II disorders, parental psychopathology, and parental socioeconomic status.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The participants in the present study were 717 youths (51% [N=366] were female) and their mothers who completed research interviews conducted in 1983, 1985–1986, and 1991–1993 (17). The participating families were a subset of 976 randomly sampled families from two upstate New York counties, with children ranging in age from 1 to 10, with whom maternal interviews had been conducted in 1975 (18). During the three follow-up interviews, which were administered by extensively trained and supervised lay interviewers, the youths and their mothers were interviewed to assess axis I and axis II disorders, as well as demographic and other psychosocial variables. The mean age of the youths was 13.8 years (SD=2.6, range=9–19) in 1983, 16.1 (SD=2.7, range=11–23) in 1985–1986, and 22.0 (SD=2.7, range=17–28) in 1991–1993. The families in this study were generally representative of families in the northeastern United States with regard to socioeconomic status and most demographic variables (17) but reflected the sampled region with regard to high proportions of Catholic (54%) and Caucasian (91%) participants. Study procedures were approved according to appropriate institutional guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained after the interview procedures were fully explained. Youths and their mothers were interviewed separately, and both interviewers were blind to the responses of the other informant. Additional information regarding the study methodology is available from previous reports (17, 18).

Assessment of Axis I Disorders and Violent Behavior

The parent and youth versions of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (19) were administered in 1983, 1985–1986, and 1991–1993 to assess anxiety, disruptive, eating, mood, and substance use disorders. One Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children module assesses a range of violent acts (arson, assault resulting in injury to another person, breaking and entering, mugging, robbery, starting serious physical fights, threats to injure others, and vandalism) committed during the past 1–4 years or during the individual’s lifetime. The focus of the present study was on violent acts that were reported in 1985–1986 or 1991–1993. Parents and youths were both interviewed, since research has demonstrated that the use of multiple informants tends to increase the reliability and validity of psychiatric diagnoses (20, 21). Mother and offspring responses to the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children were combined so that a report by either informant that a symptom was present was accepted as valid. Previous research has indicated that the reliability and validity of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children as employed in the present study are comparable to those of other structured interviews (22).

Assessment of Personality Disorders

Interview items used to assess personality disorders were drawn from the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire (23), the Disorganizing Poverty Interview (18), the parent and youth versions of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (19), and other measures (17). Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire items were modified so that they were age-appropriate and could be administered in an interview format. Although the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children was not originally developed for the purpose of diagnosing personality disorders, a number of items corresponded so closely with specific DSM-III-R criteria that they could be used to augment the assessment of personality disorder symptoms. Items were originally selected on the basis of their correspondence with DSM-III-R criteria and were combined by using algorithms developed by consensus among one psychiatrist and two clinical psychologists (11). After the publication of DSM-IV, the items selected from the study measures and the algorithms were modified to maximize correspondence with DSM-IV criteria. Items from the study protocol were added when necessary, most notably to permit assessment of depressive personality disorder. The items used to assess personality disorders are available upon request. Acceptable Cronbach’s alpha interitem reliability coefficients were obtained in 1983 and 1985–1986. With regard to personality disorder clusters, the median alpha in 1983 was 0.67 and the median alpha in 1985–1986 was 0.63.

One hundred fifty-two items were available to permit assessment of 88 (93.6%) of the 94 DSM-IV personality disorder criteria. Thirty-one items were administered to the mothers, 116 items were administered to the youths, and five items regarding the youths’ behavior and appearance were assessed by the interviewers. The overall correlation between the youths’ and the mothers’ responses to the items assessing personality disorder symptoms was significant (r=0.34, df=748, p<0.001). Thirty-six diagnostic criteria were assessed with a single interview item. The remaining 52 criteria were assessed with two or more interview items. Thresholds for determining whether responses were diagnostically significant were established on the basis of correspondence with DSM-IV criteria and statistical deviance from the sample mean. An example that illustrates the items and algorithms that were used to assess personality disorders is DSM-IV paranoid personality disorder criterion A2 (“is preoccupied with unjustified doubts about the loyalty or trustworthiness of friends or associates”). Two items were available to assess this diagnostic criterion: 1) “He/she often doesn’t trust other people” (parent item), and 2) “I often wonder if the people I know can really be trusted” (youth item). Diagnostic criterion A2 was considered present if an affirmative answer was given to either of these two items.

DSM-IV stipulates that personality disorder symptoms must be persistent in order for an adolescent to be diagnosed with a personality disorder. Therefore, adolescent personality disorder diagnoses were assigned only if youths met DSM-IV criteria in both 1983 and 1985–1986 or if they met DSM-IV criteria at one assessment and were within one criterion of the diagnosis at the other assessment. In accordance with DSM-IV criteria, antisocial personality disorder was only assessed in 1983 and 1985–1986 among those participants who were at least 18 years old.

Assessment of Parental Psychopathology and Socioeconomic Status

Parental psychopathology was assessed by using four instruments. Parental emotional problems were assessed in 1983 and 1985–1986 with the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (24). Parental substance abuse was assessed in 1983 and 1985–1986 in the maternal interview. Parental problems with police were assessed in 1975, 1983, and 1985–1986 in the maternal interview. Parental history of psychiatric disorders was determined in 1983 and 1985–1986 with items assessing treatment for a mental disorder. Parental psychopathology was considered present if significant emotional problems, substance abuse, or problems involving police were present in either parent in 1975, 1983, or 1985–1986 or if either parent had ever been treated for a mental disorder.

Parental education and parental income were assessed in 1975, 1983, and 1985–1986 during the maternal interviews. Low parental socioeconomic status was considered present if neither parent completed high school and if family income was below the U.S. poverty levels in 1975, 1983, or 1985–1986. If data regarding the father’s education was not available, the mother’s educational level was used.

Data Analytic Procedure

Analyses of contingency tables were conducted to investigate whether DSM-IV personality disorders within clusters A, B, or C during early and mid-adolescence were associated with violent acts during mid-adolescence and early adulthood. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to investigate whether adolescent personality disorders were associated with subsequent violent acts after controlling statistically for offspring age and sex, for parental psychopathology and socioeconomic status, for the presence of conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder during late childhood or early adolescence, and for co-occurring anxiety, depressive, personality, and substance use disorders during mid-adolescence. Personality disorder clusters were used in these analyses because specific personality disorders were too low in prevalence to permit analyses. Logistic regression analyses were also conducted to investigate whether personality disorder symptom totals during adolescence were associated with violent acts during adolescence and early adulthood after controlling for the aforementioned covariates. The two different sets of logistic regression analyses were conducted because, as stated in DSM-IV, categorical and dimensional approaches to personality disorder assessment can provide complementary information regarding the impairment and distress that are often associated with personality disorders.

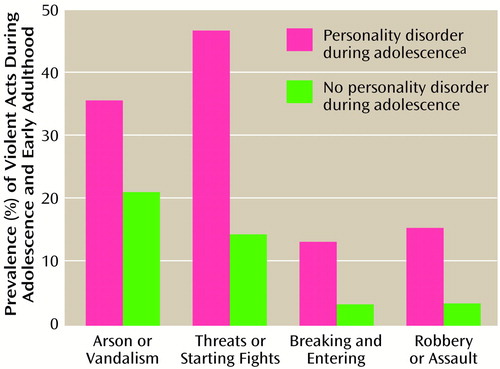

Supplemental analyses were conducted to investigate whether a diagnosis of narcissistic, paranoid, or passive-aggressive personality disorder during adolescence was associated with violent behavior during adolescence and early adulthood. As Figure 1 shows, youths with narcissistic, paranoid, or passive-aggressive personality disorder during adolescence were substantially more likely than youths without these personality disorders to commit arson or vandalism (odds ratio=2.06, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.09–3.90), to threaten to injure others or to initiate serious physical fights (odds ratio=5.96, 95% CI=3.19–11.12), to break into a house, building, store, or office (odds ratio=4.34, 95% CI=1.67–11.28), and to commit a mugging, robbery, or assault (odds ratio=4.77, 95% CI=1.94–11.73). Youths with a narcissistic, paranoid, or passive-aggressive personality disorder during adolescence remained more likely than youths without any of these personality disorders to commit one or more violent acts against others during adolescence or early adulthood after the covariates were controlled (adjusted odds ratio=3.29, 95% CI=1.55–6.96).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The prevalences of DSM-IV personality disorders during adolescence and of violent acts during adolescence and early adulthood are presented in Table 1. Of the 103 adolescents with personality disorders, 51 had a single personality disorder, and 52 had two or more. Violent acts were committed by 38% (N=39 of 103) of the subjects with a personality disorder during adolescence, a significantly higher rate than that of subjects without a personality disorder in adolescence (19% [N=117 of 614]) (χ2=18.33, df=1, p<0.001).

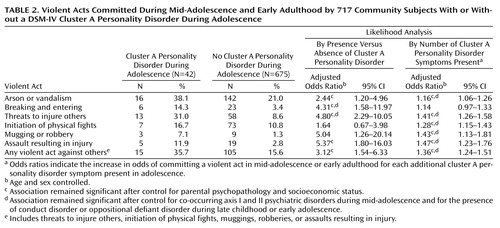

Violent Acts and Personality Disorder Clusters

Subjects with cluster A personality disorders during adolescence were significantly more likely than those without cluster A personality disorders to commit breaking and entering and to threaten to injure others during adolescence and early adulthood after all the covariates were controlled (Table 2). Each additional cluster A personality disorder symptom was associated with an increase in risk for arson or vandalism, threats to injure others, initiation of serious physical fights, mugging or robbery, assault resulting in injury to others, and any violent act against others after the covariates were controlled. Supplemental analyses indicated that a cluster A personality disorder diagnosis did not interact statistically with substance abuse to predict any violent acts.

Subjects with cluster B personality disorders during adolescence, not including antisocial personality disorder, were significantly more likely than those without cluster B personality disorders to be involved in arson or vandalism, initiate physical fights, commit a mugging or robbery, and engage in any violent act against others after the covariates were controlled (Table 3). Each additional cluster B personality disorder symptom was associated with an increase in risk for all six types of violent acts during adolescence and early adulthood after the covariates were controlled. A cluster B personality disorder diagnosis did not interact with substance abuse to predict any violent acts. A cluster C personality disorder diagnosis during adolescence was not associated with an increase in risk of committing any violent acts.

Violent Acts and Specific Personality Disorder Symptoms

As Table 1 indicates, symptoms of paranoid, narcissistic, or passive-aggressive personality disorder during adolescence were uniquely associated with an increase in risk of committing any violent act against others after the covariates were controlled. Paranoid personality disorder symptoms were associated specifically with an increase in risk of initiating physical fights. Narcissistic personality disorder symptoms were associated specifically with an increase in risk of being involved in arson or vandalism, threatening to injure others, initiating physical fights, and committing assault resulting in injury to others. Passive-aggressive personality disorder symptoms were associated specifically with an increase in risk for being involved in arson or vandalism, threatening to injure others, and initiating physical fights. Symptoms of paranoid, narcissistic, or passive-aggressive personality disorder did not interact with gender or substance abuse to predict subsequent violent acts.

Discussion

The present findings indicate that adolescents in the community with DSM-IV cluster A and cluster B personality disorders and adolescents with a greater number of narcissistic, paranoid, and passive-aggressive symptoms are more likely to commit a range of violent acts during adolescence and early adulthood. It is important to note that the present findings were obtained after controlling statistically for the youths’ age and sex, co-occurring axis I and II disorders, and parental psychopathology and socioeconomic status. Our findings suggest that it may be appropriate to ascertain histories of violence among youths who have paranoid, narcissistic, or passive-aggressive personality disorders and to consider the possibility of a personality disorder diagnosis among youths with a history of violent behavior. It will be of interest for future research to investigate whether, by identifying and treating youths who have personality disorders and a history of violent behavior, it may be possible to prevent extreme acts of violence such as homicide from occurring.

Although this is the first community-based, longitudinal prospective study to investigate the association between personality disorders during adolescence and violent behavior, the present findings are consistent with previous research indicating that several different types of personality disorders were associated with violent behavior among adults in clinical, forensic, and community samples (1μ10, 13, 14). Findings by previous researchers have indicated that cluster A (1, 2) and cluster B (2, 3, 8, 10, 13, 14) personality disorders and narcissistic (2, 10), paranoid (1, 2), and passive-aggressive (1, 2) personality disorders were associated with violent acts among adults. However, the present findings are not consistent with previous research that indicated that borderline personality disorder was associated with violent behavior among adults (2, 3, 8, 13, 14). The findings of the only other community-based study that has controlled statistically for co-occurring personality disorders indicated that borderline personality disorder was not independently associated with a history of violent behavior among adults (1), which suggests that axis II comorbidity may account for the association between borderline personality disorder and violent behavior. It will be of interest for future research to investigate whether severe forms of borderline personality disorder, such as those often present in clinical and forensic populations, are uniquely associated with violent behavior.

Some violent behaviors, such as vandalism, were relatively common in this sample. Although adolescent personality disorder symptoms were associated with increased risk for these behaviors, most of the individuals who committed these acts did not have personality disorders during adolescence. Previous research has indicated that psychological factors related to personality disorders, such as frustration, anger, emotional dysregulation, and social cognition deficiencies, are associated with adolescent violence (25). It will be of interest for future research to investigate the association between psychosocial development, familial risk factors (26), personality disorders, and violent behavior during adolescence.

Limitations of the present study also merit consideration. Because no validated structured clinical interviews were available for the assessment of personality disorders in the early 1980s, diagnostic algorithms were constructed from measures that were available to assess personality disorder symptoms in 1983 and 1985–1986. Because no firm estimate of the prevalence of personality disorders among adolescents in the community is currently available, it is not possible to determine whether personality disorders were more prevalent in this sample than in the general population. However, in accordance with DSM-IV guidelines, which require an enduring pattern of traits and behavior, clinically significant personality disorder symptom totals were required to be present in both 1983 and 1985–1986 in order for a personality disorder diagnosis to be assigned. The temporal stability of the instrument used to assess personality disorders among adolescents in the present study is comparable to the stability of structured clinical interviews that were readministered to adults over similar temporal intervals (27). The predictive validity of this instrument is supported by findings indicating that personality disorders predicted axis I disorders and suicidal behavior during early adulthood (28).

Because DSM-IV stipulates that antisocial personality disorder is not to be diagnosed unless an individual is at least 18 years old, antisocial personality disorder was assessed in only one-third of the present sample. Therefore, findings regarding antisocial personality disorder could not be reported for the full sample. The associations between cluster B personality disorders and violent acts might have been stronger if antisocial personality disorder had been assessed in the entire sample. The present findings are of particular interest because relatively effective treatments are available for personality disorders other than antisocial personality disorder (29).

|

|

|

|

Received Sept. 15, 1999; revisions received Jan. 18 and March 23, 2000; accepted May 3, 2000. From Columbia University Department of Psychiatry/New York State Psychiatric Institute; and Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York. Address reprint requests to Dr. Johnson, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1051 Riverside Dr., Unit 60, New York, NY 10032. Supported by grants from NIMH (MH-36971) to Dr. Cohen and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA-03188) to Dr. Brook.

Figure 1. Violent Behavior During Adolescence or Early Adulthood of 717 Community Subjects With or Without a Personality Disorder During Adolescencea

aNarcissistic, paranoid, or passive-aggressive personality disorder

1. Berman ME, Fallon AE, Coccaro EF: The relationship between personality psychopathology and aggressive behavior in research volunteers. J Abnorm Psychol 1998; 107:651–658Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Windle RC, Windle M: Longitudinal patterns of physical aggression: associations with adult social, psychiatric, and personality functioning and testosterone levels. Dev Psychopathol 1995; 7:563–585Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Coccaro EF, Berman ME, Kavoussi RJ: Assessment of life history of aggression: development and psychometric characteristics. Psychiatry Res 1997; 73:147–157Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Miller RJ, Zadolinnyi K, Haffner RJ: Profiles and predictors of assaultiveness for different psychiatric ward populations. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1368–1373Google Scholar

5. Hart SD, Dutton DG, Newlove T: The prevalence of personality disorder among wife assaulters. J Pers Disord 1993; 7:329–341Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Tardiff K, Marzuk PM, Leon AC, Portera L: A prospective study of violence by psychiatric patients after hospital discharge. Psychiatr Serv 1997; 48:678–681Link, Google Scholar

7. Murphy CM, Meyer SL, O’Leary KD: Family of origin violence and MCMI-II psychopathology among partner assaultive men. Violence Vict 1993; 8:165–176Medline, Google Scholar

8. Else LT, Wonderlich SA, Beatty WW, Christie DW, Staton RD: Personality characteristics of men who physically abuse women. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1993; 44:54–58Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Dinwiddie SH: Psychiatric disorders among wife batterers. Compr Psychiatry 1992; 33:411–416Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Rothschild B, Dimson C, Storaasli R, Clapp L: Personality profiles of veterans entering treatment for domestic violence. J Family Violence 1997; 12:259–274Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Bernstein DP, Cohen P, Velez CN, Schwab-Stone M, Siever LJ, Shinsato L: Prevalence and stability of the DSM-III-R personality disorders in a community-based survey of adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1237–1243Google Scholar

12. Johnson JG, Rabkin JG, Williams JBW, Remien RH, Gorman JM: Difficulties in interpersonal relationships associated with personality disorders and axis I disorders: a community-based longitudinal investigation. J Pers Disord 2000; 14:42–56Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Lish JD, Kavoussi RJ, Coccaro ER: Aggressiveness, in Personality Characteristics of the Personality Disordered. Edited by Costello CG. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1996, pp 24–47Google Scholar

14. Widiger TA, Trull TJ: Personality disorders and violence, in Violence and Mental Disorder: Developments in Risk Assessment. Edited by Monahan J, Steadman HJ. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1994, pp 203–226Google Scholar

15. Bland R, Orn H: Family violence and psychiatric disorder. Can J Psychiatry 1986; 31:129–137Medline, Google Scholar

16. Robins LN, Tipp J, Przybeck T: Antisocial personality, in Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. Edited by Robins LN, Regier DA. New York, Free Press, 1991, pp 258–290Google Scholar

17. Cohen P, Cohen J: Life Values and Adolescent Mental Health. Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1996Google Scholar

18. Kogan LS, Smith J, Jenkins S: Ecological validity of indicator data as predictors of survey findings. J Soc Service Res 1977; 1:117–132Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Costello EJ, Edelbrock CS, Duncan MK, Kalas R: Testing of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) in a Clinical Population: Final Report to the Center for Epidemiological Studies, NIMH. Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh, 1984Google Scholar

20. Bird HR, Gould M, Staghezza B: Aggregating data from multiple informants in child psychiatry epidemiological research. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:78–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Piacentini J, Cohen P, Cohen J: Combining discrepant diagnostic information from multiple sources: are complex algorithms better than simple ones? J Abnorm Psychol 1992; 20:51–63Google Scholar

22. Cohen P, O’Connor P, Lewis SA, Malachowski B: A comparison of the agreement between DISC and K-SADS-P interviews of an epidemiological sample of children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1987; 26:662–667Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Hyler SE, Rieder RO, Williams JBW, Spitzer RL, Hendler J, Lyons M: The Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire: development and preliminary results. J Pers Disord 1988; 2:229–237Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L: The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci 1974; 19:1–15Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Loeber R, Hay D: Key issues in the development of aggression and violence from childhood to early adulthood. Annu Rev Psychol 1997; 48:371–410Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Farrington DP: Early predictors of adolescent aggression and adult violence. Violence Vict 1989; 4:79–100Medline, Google Scholar

27. Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Skodol A, Brook J: Change in personality disorder symptom levels between childhood and adulthood: a community-based longitudinal investigation. Acta Psychiatr Scand (in press)Google Scholar

28. Johnson JG, Cohen P, Skodol A, Oldham JM, Kasen S, Brook J: Personality disorders in adolescence and risk of major mental disorders and suicidality during adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:805–811Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Perry JC, Banon E, Ianni F: Effectiveness of psychotherapy for personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1312–1321Google Scholar