Depression in Schizophrenia: Perspective in the Era of “Atypical” Antipsychotic Agents

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The author sought to provide a contemporary understanding of depression in schizophrenia and promote a treatment orientation. METHOD: Computer and library-based resources were used to review the literature on depression in schizophrenia. RESULTS: Despite multiple definitions of “depression,” a substantial rate of depression has consistently been found in patients with schizophrenia. A differential diagnosis can be used to advance the understanding and treatment of depression in schizophrenia, and changes in response to the advent of atypical antipsychotic agents can be understood in the context of this differential diagnosis paradigm. CONCLUSIONS: Depression is an important co-occurring syndrome in schizophrenia. In at least some schizophrenic patients, the stress-vulnerability model has potential as an integrating concept concerning the relationship between depression and psychosis.

Although schizophrenia and depression have historically been considered to be separate diagnostic disorders, the observation has repeatedly been made that, from a symptom perspective, depression-like phenomenology occurs quite frequently in schizophrenia (1–4). In the early decades of psychopharmacology, however, it seemed most important to differentiate schizophrenia and depression in order to define most clearly which patients should be treated with antipsychotic agents and which with antidepressants. Nevertheless, the occurrence of the phenomenology of depression in a substantial percentage of patients with schizophrenia (as well as psychosis in patients with depression) has kept alive the twin issues of the appropriate descriptive boundaries between the two disorders and the best approaches to treatment. Indeed, these issues assume added importance, since it has been found that the occurrence of depression in schizophrenia has often been associated with worse outcome (5), impaired functioning, personal suffering (6), higher rates of relapse or rehospitalization (7–10), and even suicide (8, 11, 12)—a tragic event that terminates the lives of an estimated 10% of patients with schizophrenia (11, 13).

This article considers our current conceptualizations of depression-like symptoms in patients with schizophrenia, documents their common occurrence, and reviews the differential diagnosis of conditions that such symptoms might reflect. It also presents a potential integrating model that may facilitate the understanding of depression in at least some individuals with schizophrenia. Last, this article explores the implications for treatment as we enter a new era in schizophrenia pharmacotherapy occasioned by the advent of the so-called atypical antipsychotic agents.

Depression in Schizophrenia

Affect, Symptom, or Syndrome?

Some of the confusion attending the term “depression” in schizophrenia is attributable to the question of whether it is the affect of depression, the symptom of depression, or the syndrome of depression that is being considered. This confusion is not limited to patients with schizophrenia, of course, but it certainly has confounded the schizophrenia literature. Depression as an affect reflects an individual’s momentary mood state on the subjective experience spectrum from happiness to sadness as he or she interacts with his or her internal and external environments. It is not, in itself, pathological as long as it is situationally appropriate (e.g., a touching movie may elicit sad affect). Depression as a symptom is a sad mood state that causes a person distress. It is an unwanted painful feeling and can be a source of complaint. However, it is not necessarily enduring or accompanied by other features that are required for the diagnosis of the syndrome of depression. The depression syndrome is a complex of features that typically involves the symptom of depression but also includes cognitive and vegetative features such as pessimism, guilt, impaired concentration, lack of confidence, loss of interest or pleasure, and disturbances in sleep, appetite, and energy level. Unfortunately, the literature on depression in schizophrenia is often imprecise as to whether the affect, symptom, or syndrome of depression is involved, and these three meanings have often been employed loosely and interchangeably. The literature needs to be read carefully in this regard, and, most important, patients need to be listened to closely to understand the type of “depression” that they are experiencing. Differences in definition may account for some of the discrepancies in the reported occurrence rates and treatment responses of depression in schizophrenia, and this situation has contributed to the creation of the proposed syndromal definition “postpsychotic depressive disorder of schizophrenia” in Appendix B of DSM-IV (pp. 711–712).

Rates of Occurrence of Depression in Schizophrenia

Over three dozen published studies have examined rates or dimensions of depression in schizophrenia. These have been reviewed elsewhere (4, 6, 14–18). Investigations have varied considerably in terms of the definitions employed for schizophrenia and depression, the observed interval, the assessment methodology, and the patient status. Nevertheless, at least some meaningful point prevalence of depression was observed in each study in which it was assessed. Proportions of patients manifesting depression ranged from a high of 75% to a low of 7%. The 75% figure reflected at least one positive assessment of depression according to either of two criteria (one syndromal, the other based on a rating scale score) among patients with first-episode schizophrenia evaluated longitudinally on a weekly to monthly basis for up to 5 years (19). The 7% observation involved a single cross-sectional assessment of a rating scale item in chronically hospitalized patients with schizophrenia in whom an effort was made to distinguish depression from negative symptoms (20). The modal rate of depression for all reports was 25% (3, 4, 7, 14).

Symptom factor analysis studies that have attempted to go beyond the basic positive/negative symptom distinction by expanding to five dimensions have identified a depression or anxiety/depression factor, whereas those studies that used fewer dimensions have not (15–18). Results of factor analyses, of course, are dependent on exactly what symptom items are employed, and in this way initial assumptions can impact results substantially.

Differential Diagnosis of Depression in the Course of Schizophrenia

Medical/Organic Factors

A number of medical/organic factors can present as depression in patients with schizophrenia (21). These include cardiovascular disorders, pulmonary infections, autoimmune diseases, anemia, cancer, and metabolic, neurological, and endocrine disorders. Various pharmaceuticals used in medical treatment such as β blockers, other antihypertensive agents, sedative hypnotics, antineoplastics, barbiturates, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, sulfonamides, and indomethacin can cause depression as a side effect. Depression can also accompany the discontinuation of other prescribed medications such as corticosteroids and psychostimulants. Used or abused substances such as alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, or narcotics can contribute to depression either on the basis of acute use, chronic use, or discontinuation. It is also important to note that the discontinuation of two very commonly used legal substances, nicotine and caffeine, can lead to withdrawal states that potentially mimic depression (22, 23). Recent “smoke-free” and “decaf” policies on many inpatient units may have led to higher rates of this form of depression.

Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia

The negative symptom syndrome of schizophrenia overlaps with the syndrome of depression in a number of important respects (24–27). Diminished interest, pleasure, energy, or motivation along with psychomotor retardation and impaired ability to concentrate are relevant overlapping features. However, certain other symptoms may be more distinguishing (28–31). Blunted affect, for example, suggests negative symptoms, whereas distinct blue mood or cognitive features such as guilt or suicidal thoughts suggest depression. Unfortunately, differentiating these two states can sometimes be difficult if patients lack the interpersonal communication skills to articulate their internal subjective states well.

Neuroleptic-Induced Dysphoria

Dopamine synapses are involved in brain pathways mediating “reward” (32, 33). Therefore, dopamine blockade by a neuroleptic drug could theoretically lead to anhedonia and, perhaps, depression. Indeed, a state of dysphoria is commonly described by neuroleptic-treated patients (34), a number of older anecdotal reports have suggested a link between neuroleptic use and depression (35–39), and one study found more anhedonia and depression in maintenance-phase schizophrenic patients who were taking neuroleptics than in others who were not (33). Another study found a positive relationship between haloperidol plasma levels and depressive symptoms in the context of a positive association between extrapyramidal symptoms and depressive symptoms (40), and impairments of quality of life related to neuroleptic-induced dysphoria have been reported (41). Nevertheless, the preponderance of controlled-study evidence tends to refute the proposition that neuroleptic medication is regularly responsible for the development of depressive states in schizophrenia (4 , 42). Prospective observations that have followed schizophrenic patients through the treatment of acute psychotic episodes suggest that depressive symptoms were present before the neuroleptic was given and tended to subsequently subside (20, 42–46). Studies that compared patients with schizophrenia who were being treated with neuroleptic medications versus those who were not did not find that neuroleptic-treated patients manifested more depression (20, 47–49). And studies examining schizophrenic patients with and without depression found that these two groups did not show any differences in neuroleptic doses or blood levels (8, 50–54). Nevertheless, one biological possibility is that schizophrenia may represent a basic disorder of dopamine regulation (55) in which “brittle” patients are vulnerable to dopamine storms (psychosis) and droughts (negative symptoms). In this situation, the administration of more than the minimum required neuroleptic (dopamine-blocking) medication could exacerbate negative symptoms, thereby possibly contributing to the impression of neuroleptic-induced depression.

Neuroleptic-Induced Akinesia

Rifkin et al. (56, 57) and Van Putten and May (58) went beyond the original “large muscle stiffness” definition of akinesia to describe a more subtle but equally debilitating extrapyramidal side effect of neuroleptic treatment involving impaired ability to initiate and sustain motor behavior. Patients with this form of akinesia may or may not have the classical parkinsonian feature of decreased accessory motor movements. However, they act “as if their starter motor is broken,” and they consequently appear to lack spontaneity. Since so much of human interchange, such as holding a conversation or participating in activities, involves the initiation or maintenance of motor behavior, this side effect leads to exclusion from much of what is normal in life. Patients themselves may attribute this effect to “laziness,” experiencing guilt or shame. Blue mood can also accompany this condition, possibly as a primary issue (58), making it virtually indistinguishable clinically from depression. Unfortunately, most studies of depression in neuroleptic-treated patients have not adequately considered this form of akinesia as a potentially confounding factor.

Neuroleptic-Induced Akathisia

Akathisia is another extrapyramidal side effect of neuroleptic treatment that, in subtle presentation, can easily be confounded with depression (59). Patients with akathisia behave “as if their starter motor won’t stop” and often experience this state as substantially dysphoric (59, 60). Indeed, akathisia has been associated with both suicidal ideation and—perhaps as a consequence of a general tendency toward motor action—suicidal behavior (61, 62). As with akinesia, akathisia has seldom been considered as a possible confound in studies of depression in schizophrenia.

Reactions to Disappointment or Stress

Reactions to disappointments, a sense of loss or powerlessness, or awareness of psychotic symptoms or psychological deficits can certainly present as or contribute to depression, especially when depression follows closely after a stressful event or exacerbation of schizophrenia (3, 10, 63, 64). Such reactions are of two types: acute and chronic. An acute reaction to disappointment or stress is suggested by the parallel history of a recent compatible event and is sometimes validated by the patient making a psychological connection between that event and a mood change. Acute reactions are generally brief, lasting hours, days, or at most weeks, and may be responsive to supportive interventions or counterbalancing positive experiences. Chronic reactions to disappointment or stress have also been termed the demoralization syndrome (65–67). By definition, these last longer and are apt to be more difficult to distinguish from other forms of depression. Indeed, schizophrenic patients who experience less of a sense of control regarding their illness (one of the hallmarks of demoralization) have been found to be more likely to experience depression (10). Demoralized patients with extended histories of disappointment or failure can also develop the conviction that a useful or satisfying life is impossible, further blurring the distinction from other forms of depression. Demoralization is important to diagnose because it may be more responsive than other depressed states to appropriately targeted psychosocial interventions.

“Postpsychotic Depression”

In earlier times, the term “postpsychotic depression” was used to describe a dysphoric state that immediately followed a psychotic episode (3). In the sense that this was reactive to disappointment or stress, such an episode might belong in the previous category. DSM-IV now suggests that the term “postpsychotic depression” be used to describe depression that occurs at any time after a psychotic episode in schizophrenia—even after a prolonged interval. This definition would include many of the other defined categories in this article.

Prodrome of Psychotic Relapse

Investigations into the course of psychotic decompensation in schizophrenia have frequently noted the appearance of depression-like symptoms (9, 20, 45, 68–72). Anxiety, withdrawal, guilt, and shame commonly accompany dysphoria in this situation. Clues to the underlying circumstance of psychotic relapse may be found, however, in signs or symptoms of early psychotic decompensation, such as hypervigilance, perceptual disturbances, or the overinterpretation of perceptions or events. The appearance of a depression-like state as a prodrome of a new psychotic episode is a short-lived phenomenon, often lasting only a couple days to a couple weeks, before being superseded by more prominent and definitive psychotic symptoms.

Schizoaffective Depression

The term “schizoaffective disorder” was first used in the early 1930s to describe patients showing an overlap of features of schizophrenia and affective illness (73). Over time, schizoaffective disorder has been defined differently according to various diagnostic schemes (74–76), which has resulted in variations in the boundary between schizoaffective depression and depression in schizophrenia. In DSM-IV, schizoaffective disorder refers to patients in whom a full affective syndrome coincides with the florid psychotic syndrome but who also have substantial periods of psychosis in the absence of an affective syndrome. This definition does not resolve the etiology or pathophysiology of the condition, and debate continues as to whether schizoaffective disorder should be considered a type of schizophrenia, a type of affective disorder, sometimes one and sometimes the other, a distinct entity, a domain on a continuum between schizophrenia and affective disorder, a co-occurrence of two distinct diatheses, or an erroneous concept altogether. The descriptive diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, however, has value in defining phenomenologically an interesting patient group for which biological studies and clinical trials can be undertaken.

The Stress-Vulnerability Model as a Potential Integrating Concept

The well-known stress-diathesis model of schizophrenia (77, 78) depicts the psychosis of schizophrenia as a final common path of neuropsychiatric decompensation. The central notion is that vulnerability to schizophrenic psychosis occurs on a continuum in the population, from a tiny fraction of persons with such a strong vulnerability that psychosis is virtually inevitable to the overwhelming majority of the population in whom the vulnerability is so slight that the risk of psychosis is virtually negligible. In between, there is a small, yet meaningful, portion of individuals who could become psychotic if stressed enough but who could also survive without psychosis if not sufficiently stressed.

The stress in this model can be biological or psychosocial, and many relevant stresses have been described. Intrauterine viral infection, poor prenatal nutrition, birth injuries, and childhood head trauma would all be examples of early-life biological stressors. Substance abuse is an example of a biological stressor occurring more proximally to a first or subsequent psychotic episode. Traumatic interpersonal experiences, more longitudinal psychic stresses (such as chaotic, abusive, or high “expressed emotion” environments), and lack of opportunity to develop adequate compensating coping skills are examples of psychosocial stressors.

It is provocative to speculate that the activation of an affective diathesis, such as depression, could act as a sufficient stressor precipitating psychosis in people with otherwise modest vulnerabilities. Certainly depression is a highly stressful state psychologically, and it is possible that it is stressful in relevant biological ways as well (e.g., insomnia, hormonal changes, neurotransmitter effects). And since within the vulnerability continuum there are many more people with moderate than with extreme vulnerabilities, a reasonable percentage of manifest psychotic episodes could be precipitated by depressive episodes in individuals otherwise only moderately vulnerable to psychosis. If this is the case, it might help to explain some of the “depression” seen in the course of schizophrenia, including, notably, the depression-like symptoms observed early in the course of some psychotic decompensations. This hypothesis is consistent with the observation that dysphoria is associated more with positive symptoms than with negative symptoms in schizophrenia (79, 80). It might also help explain the finding that maintenance antidepressant treatment, administered for the purpose of averting depressive relapses in schizophrenic patients with histories of syndromal postpsychotic depression, also seemed to reduce their rate of psychotic exacerbations (81).

Depression in Schizophrenia and “Atypical” Antipsychotics

The advent of so-called atypical antipsychotic agents may be ushering in a new or “third” era with regard to dealing with schizophrenia. The first era was the preneuroleptic epoch, during which many detailed descriptions contributed to our understanding of the natural history of schizophrenia. After neuroleptic agents were introduced in the 1950s, it quickly became apparent that a remarkable curtailing of many dramatic psychotic manifestations was possible, even if many negative or cognitive symptoms persisted. Subsequently, almost all patients were treated with these agents, both acutely and in routine maintenance. A new and at least somewhat milder condition resulted: neuroleptic-treated schizophrenia. It was during this second era that most studies of “depression in schizophrenia” were undertaken, which form the basis of our current recognition and understanding of this condition.

There are several reasons to suspect that schizophrenia treated with atypical antipsychotics may prove to be at least a somewhat different condition than schizophrenia treated with conventional neuroleptics from the point of view of depression, although this, of course, still needs to be confirmed by appropriate careful investigations. First, atypical antipsychotic agents have a greatly reduced extrapyramidal side effect profile (82–86). Since akinesia and akathisia figure prominently in the differential diagnosis of what appears as depression in schizophrenia, this issue alone could be responsible for a notably different expression of depression in schizophrenia. Second, since atypical agents seem to rely much less exclusively on dopaminergic blockade for their therapeutic activity (83, 87–90), they might circumvent the mechanism of neuroleptic-induced dysphoria that could contribute to the depression syndrome. Third, atypical antipsychotics have frequently been reported to be superior to standard neuroleptics in the treatment of negative symptoms (83–86, 91–96), which can sometimes appear similar to depression.

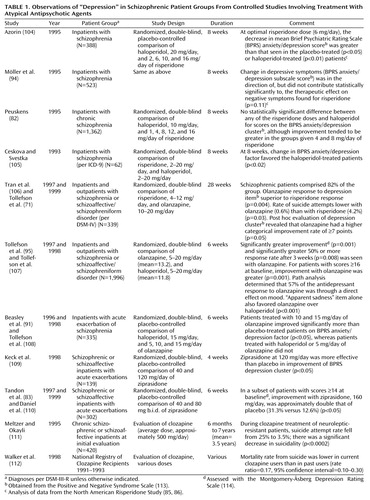

Either through effects on negative symptoms or by some other means, atypical antipsychotics may lead to superior outcomes for patients with schizophrenia, as suggested by quality-of-life measures (97, 98). In this event, both acute and chronic reactions to disappointment or stress may be reduced. It is also possible that at least some atypical antipsychotic agents (so far demonstrated clearly only for clozapine in the treatment of refractory schizophrenia) may be superior to standard neuroleptics in the treatment of psychosis itself (93, 99). If this is the case, depression associated with the prodrome of psychotic relapse might possibly be reduced. Another mechanism whereby psychotic relapse may be averted through atypical antipsychotic use is by means of better medication compliance (95, 100–102), perhaps on the basis of a more favorable side effect profile (83, 85, 86, 103). Last, it is possible that atypical antipsychotic agents have direct antidepressant activity on their own. Table 1 reviews the controlled studies of atypical antipsychotic agents that make reference to the issue of depression. Several of these suggest a benefit for atypical antipsychotic agents in this regard. It is relevant to note, in this context, that conventional neuroleptics themselves have been found to have at least some degree of antidepressant activity (42, 107, 115–119), perhaps particularly in patients with agitated depression. Indeed, it may be features of agitation or excitement within the depression syndrome that may be particularly helped by atypical antipsychotics as well (120, 121), although studies have not been specifically designed to tease this out definitively. In addition to the studies cited in Table 1, a number of anecdotal reports also suggest that the atypical antipsychotics have superior antidepressant properties or, in the case of clozapine, antisuicidal properties when compared with conventional neuroleptics (87, 122–129), with but a single study suggesting the contrary (105).

Obviously, combinations of any or all of these effects could potentially be responsible for more favorable depression profiles in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics versus conventional neuroleptics. Further research is needed to clarify the shape and size of such an effect and to probe its possible mechanisms. Nevertheless, as summarized in Table 1, the controlled observations to date are intriguing with regard to potentially reduced rates of depression-like morbidity among schizophrenic patients receiving atypical antipsychotics.

Thirteen of the studies in Table 1 either are, or are reanalyses of, prospective randomized trials. Twelve of the 13 present evidence, of various strengths, that olanzapine, risperidone, or ziprasidone may have an antidepressant spectrum of activity in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. No published study could be found that tested the activity of quetiapine in this regard. One trial (105), the smallest of the group, presented data suggesting that risperidone may be inferior to haloperidol in terms of BPRS anxiety/depression factor improvement. Whether this result has to do with the relatively high dose range of risperidone employed (as much as 20 mg/day) or the lower dose range of haloperidol (as low as 2 mg/day) compared to the other studies is unclear. Altogether, eight of the studies in Table 1 used haloperidol as a comparison medication. The possibility, however, that extrapyramidal side effects of haloperidol created a spurious impression of superior antidepressant activity for the atypical antipsychotics in these studies is lessened by the sophisticated path-analysis examination in the largest of the studies (95, 96, 107). One study suggested that olanzapine was superior to risperidone in alleviating depression (71), and two studies found ziprasidone to be superior to placebo (83, 109). The final two studies in Table 1 present evidence suggesting that suicidality may be reduced in patients receiving clozapine. Suicidality is not a direct measure of depression, and other factors such as psychotic disorganization or terror can also be associated with self-destructive behavior in this population. However, it is not unreasonable to speculate that suicidality can still serve as a logical, although imperfect, proxy for depression in schizophrenia, especially since it represents such an important negative outcome.

The broad array of affinities for receptor sites attributable to the novel atypical antipsychotic agents (including a wide array of 5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT], dopamine [other than D2], and muscarinic sites as well as α1-noradrenergic and histamine-1 receptor sites) suggest a variety of potential mechanisms through which atypical antipsychotics might exercise antidepressant effects (107, 130). Interest in both depression (131) and schizophrenia (132) has focused on the 5-HT2 binding site, but it would be premature to conclude that this is the key or exclusive site of action, and more research is needed. Useful clues in this area may also be gleaned from the existing experience involving the use of tricyclic antidepressants as adjunctive agents in the treatment of depression in schizophrenia (14). An extended consideration of mechanistic biochemical issues concerning depression, schizophrenia, and atypical antipsychotic agents goes beyond the scope of this article. Suffice it to say that there are many differences in receptor level activity among the different atypical antipsychotic agents that may prove to be relevant to their eventually being found to have differing clinical antidepressant profiles. They therefore should not necessarily be considered to be a homogeneous group of agents nor should the effect—or lack of effect—found with one agent necessarily be assumed to apply to other atypical agents.

Treatment Strategies

A rational approach to treating depression in schizophrenia flows from considering the differential diagnosis. Excluding organic etiologies, the first consideration concerning a newly emergent depressive reaction in schizophrenia is whether it is a transient reaction to disappointment or stress or the prodrome of a new psychotic episode. The most prudent initial response is to increase surveillance and provide additional nonspecific support. A transient reaction to disappointment or stress will soon resolve spontaneously, and an incipient psychotic episode will soon declare itself. In the latter case, the increased surveillance will allow the best chance for the new episode to be detected promptly and “nipped in the bud” by appropriate interventions with antipsychotic medication.

If an episode of depression persists in a patient treated with a conventional neuroleptic, the question next arises whether the neuroleptic medication is responsible for the depression-like symptoms, either as an extrapyramidal side effect (akinesia or akathisia) or as a form of direct neuroleptic-induced dysphoria. There are three ways that such a situation could be approached: 1) neuroleptic dose reduction, if there is leeway to accomplish this safely; 2) introduction or upward titration of an antiparkinsonian medication (likely to be useful for akinesia but less likely for akathisia), a benzodiazepine, or β blocker (the latter two being likely to be useful for akathisia [133]); or 3) substitution of an atypical antipsychotic for the conventional neuroleptic.

If the episode of depression persists in a patient already being treated with an atypical antipsychotic, the existing literature gives less guidance. Again, dose reduction is a possibility if there is leeway for this, especially if the antipsychotic agent is risperidone, which has at least a modest degree of parkinsonian side effects in the higher dose range (88). Antiparkinsonian medication is another option, especially in conjunction with risperidone for the same reason. Anticholinergic antiparkinsonian medication may be an interesting option as well, since it is possible that it has its own antidepressant activity (27, 134) or anti-negative-symptom action (135). However, an anticholinergic antiparkinsonian agent would not be likely to be a felicitous choice in a patient receiving clozapine, since the combined anticholinergic activity might lead to too great a risk of autonomic side effects. Substituting one atypical antipsychotic agent for another is an additional possibility.

In antipsychotic-treated schizophrenic patients who are not flagrantly psychotic, persisting episodes of depression that do not respond to antiparkinsonian agents may respond to the addition of an adjunctive antidepressant medication (4, 14, 136–139). Most of the literature supportive of this intervention has focused on conventional neuroleptic-treated outpatients receiving adjunctive tricyclic antidepressants (4, 6, 14). The study that was most positive involved full syndromal depression criteria and continued antiparkinsonian medication throughout the antidepressant trial (136). It is certainly plausible, however, that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants would be useful as well, and some early results support this (140, 141). Adjunctive monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) might also be useful for depression in schizophrenia, although the literature is sparse (142). It is of further interest that there have been some encouraging results involving adjunctive SSRIs (140, 141, 143–147), MAOIs (141, 148–150), and trazodone (151) in double-blind trials treating negative symptoms in schizophrenia. No prospective randomized study has yet been published, however, involving an adjunctive antidepressant added to an atypical antipsychotic agent in depressed patients with schizophrenia. Also of interest is that, although it may well be useful, ECT has not been specifically studied in the treatment of depression in patients with schizophrenia.

Additionally, lithium may be a useful adjunct in at least some cases of depression in schizophrenia, although definitive trials have not been published. Most reports concerning the use of lithium in schizophrenia have focused on its acute use during psychotic exacerbations rather than its extended use during maintenance-phase treatment (138, 152). The indicators most frequently cited in the literature as being of favorable prognostic significance for lithium response in schizophrenia have been excitement, overactivity, and euphoria. Nevertheless, depressive symptoms have occasionally been suggested as features indicative of a favorable adjunctive lithium response in schizophrenia (153). Other favorable prognosticators mentioned for lithium response in schizophrenia are the presence of previous affective episodes, a family history of affective illness, and an overall episodic nature to the clinical course (154).

Finally, although the focus of treatment discussed in this article has been primarily pharmacologic, any discussion of treatment strategies for depression in schizophrenia is incomplete without consideration of psychosocial interventions. Appropriately controlled studies of psychosocial interventions are, of course, notoriously complex and have not been carried out in a specifically depressed schizophrenic population. But this does not mean that they are not useful. There is little doubt that appropriately applied psychosocial strategies, such as stress reduction, psychoeducation, skill-building, problem-solving techniques, and family interventions designed to minimize excessive expressed emotion can be helpful (155). Strategies that foster hope, confidence, and self-esteem and interventions that contribute to real-life success experiences may be quite beneficial as well.

Conclusions

In summary, depression is well known to occur during the course of schizophrenia in many patients and contributes substantially to the morbidity—even mortality—of this disorder. “Depression” in schizophrenia, however, is heterogeneous, and the best approaches to its understanding and treatment are based on an appropriate differential diagnosis. Additional investigations will be necessary to fully appreciate the place of depressive symptoms in the conceptualization of schizophrenia and the best uses of contemporary therapeutic options, including atypical antipsychotic agents.

|

Received March 8, 1999; revisions received Oct. 26, 1999, and Feb. 15, 2000; accepted Feb. 25, 2000. From the Hillside Hospital Division of the North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System. Address reprint requests to Dr. Siris, Kaufmann Building, Hillside Hospital, 75-59 263rd St., Glen Oaks, NY 11004; [email protected] (e-mail). The author thanks Pfizer Inc for its support in this project.

1. Bleuler E: Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias (1911). Translated by Zinkin J. New York, International Universities Press, 1950Google Scholar

2. Burrows GD, Judd LL, Fleischhacker WW, Andreasen NC: Current concepts of affective disorders in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry Monograph 1998; 16:2–8Google Scholar

3. McGlashan TH, Carpenter WJ Jr: Postpsychotic depression in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:231–239Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Siris SG: Diagnosis of secondary depression in schizophrenia: implications for DSM-IV. Schizophr Bull 1991; 17:75–98Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Falloon I, Watt DC, Shepherd M: A comparative controlled trial of pimozide and fluphenazine decanoate in the continuation therapy of schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1978; 8:59–70Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Siris SG: Depression in the course of schizophrenia, in Management of Schizophrenia With Comorbid Conditions. Edited by Hwang MY, Bermanzohn PC. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press (in press)Google Scholar

7. Mandel MR, Severe JB, Schooler NR, Gelenberg AJ, Mieske M: Development and prediction of postpsychotic depression in neuroleptic-treated schizophrenics. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:197–203Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Roy A, Thompson R, Kennedy S: Depression in chronic schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1983; 142:465–470Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Johnson DAW: The significance of depression in the prediction of relapse in chronic schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 152:320–323Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Birchwood M, Mason R, Macmillan F, Healy J: Depression, demoralization and control over psychotic illness: a comparison of depressed and non-depressed patients with a chronic psychosis. Psychol Med 1993; 23:387–395Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Caldwell CB, Gottesman II: Schizophrenics kill themselves too: a review of risk factors for suicide. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16:571–589Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Heilä H, Isometsä ET, Henriksson MM, Heikkinen ME, Marttunen MJ, Lönnqvist JK: Suicide and schizophrenia: a nationwide psychological autopsy study on age- and sex-specific clinical characteristics of 92 suicide victims with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1235–1242Google Scholar

13. Fenton WS, McGlashan TH, Victor BJ, Blyler CR: Symptoms, subtype, and suicidality in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:199–204Link, Google Scholar

14. Siris SG: Depression and schizophrenia, in Schizophrenia. Edited by Hirsch SR, Weinberger DR. Cambridge, Mass, Blackwell Science, 1995, pp 128–145Google Scholar

15. Norman RMG, Malla AK, Cortese L, Diaz F: Aspects of dysphoria and symptoms of schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1998; 28:1433–1441Google Scholar

16. Müller MJ, Wetzel H: Dimensionality of depression in acute schizophrenia: a methodological study using the Bech-Rafaelsen Melancholia Scale (BRMES). J Psychiatr Res 1998; 32:369–378Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Andreasen NC, Arndt S, Alliger R, Miller D, Flaum M: Symptoms of schizophrenia: methods, meanings, and mechanisms. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:341–351Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Lindenmeyer JP, Grochowski S, Hyman RB: Five factor model of schizophrenia: replication across samples. Schizophr Res 1995; 14:229–234Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Koreen AR, Siris SG, Chakos M, Alvir J, Mayerhoff D, Lieberman J: Depression in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1643–1648Google Scholar

20. Hirsch SR, Jolley AG, Barnes TRE, Liddle PF, Curson DA, Patel A, York A, Bercu S, Patel M: Dysphoric and depressive symptoms in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1989; 2:259–264Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Bartels SJ, Drake RE: Depressive symptoms in schizophrenia: comprehensive differential diagnosis. Compr Psychiatry 1988; 29:467–483Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Dalack GW, Healy DJ, Meador-Woodruff JH: Nicotine dependence in schizophrenia: clinical phenomena and laboratory findings. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1490–1501Google Scholar

23. Griffiths RR, Mumford GK: Caffeine—a drug of abuse? in Psychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress. Edited by Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ. New York, Raven Press, 1995, pp 1699–1713Google Scholar

24. Andreasen NC, Olsen S: Negative v positive schizophrenia: definition and validation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:789–794Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Carpenter WT Jr, Heinrichs DW, Alphs LD: Treatment of negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull 1985; 11:440–452Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Siris SG, Adan F, Cohen M, Mandeli J, Aronson A, Casey E: Postpsychotic depression and negative symptoms: an investigation of syndromal overlap. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:1532–1537Google Scholar

27. Bermanzohn PC, Siris SG: Akinesia: a syndrome common to parkinsonism, retarded depression, and negative symptoms. Compr Psychiatry 1992; 33:221–232Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Lindenmayer J-P, Grochowski S, Kay SR: Schizophrenic patients with depression: psychopathological profiles and relationship with negative symptoms. Compr Psychiatry 1991; 32:528–533Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Norman RMG, Malla AK: Dysphoric mood and symptomatology in schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1991; 21:897–903Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Kuck J, Zisook S, Moranville JT, Heaton RK, Raff DL: Negative symptomatology in schizophrenic outpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:510–515Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Kibel DA, Laffont I, Liddle PF: The composition of the negative syndrome of chronic schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 162:744–750Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Wise RA: Neuroleptics and operant behaviour: the anhedonia hypothesis. Behav Brain Sci 1982; 5:39–87Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Harrow M, Yonan CA, Sands JR, Marengo J: Depression in schizophrenia: are neuroleptics, akinesia, or anhedonia involved? Schizophr Bull 1994; 20:327–338Google Scholar

34. Awad GA: Subjective response to neuroleptics in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1993; 19:609–618Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. DeAlarcon R, Carney MWP: Severe depressive mood changes following slow-release intramuscular fluphenazine injection. Br Med J 1969; 3:564–567Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Floru L, Heinrich K, Wittek F: The problem of post-psychotic schizophrenic depressions and their pharmacological induction. Int Pharmacopsychiatry 1975; 10:230–239Medline, Google Scholar

37. Galdi J, Rieder RO, Silber D, Bonato RR: Genetic factors in the response to neuroleptics in schizophrenia: a pharmacogenetic study. Psychol Med 1981; 11:713–728Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Johnson DAW: Depressions in schizophrenia: some observations on prevalence, etiology, and treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1981; 291:137–144Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Galdi J: The causality of depression in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1983; 142:621–625Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Krakowski M, Czobor P, Volavka J: Effect of neuroleptic treatment on depressive symptoms in acute schizophrenic episodes. Psychiatry Res 1997; 71:19–26Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Browne S, Garavan J, Gervin M, Roe M, Larkin C, O’Callighan E: Quality of life in schizophrenia: insight and subjective response to neuroleptics. J Nerv Ment Dis 1998; 186:74–78Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Knights A, Hirsch SR: “Revealed” depression and drug treatment for schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:806–811Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Möller HJ, vonZerssen D: Depressive states occurring during the neuroleptic treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1982; 8:109–117Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Leff J, Tress K, Edwards B: The clinical course of depressive symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1988; 1:25–30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J, Mintz J: The temporal relationship between depressive and psychotic symptoms in recent-onset schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:179–182Link, Google Scholar

46. Nakaya M, Ohmori K, Komahashi T, Suwa H: Depressive symptoms in acute schizophrenic inpatients. Schizophr Res 1997; 25:131–139Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Hirsch SR, Gaind R, Rohde PD, Stevens BC, Wing JT: Outpatient maintenance of chronic schizophrenic patients with long-acting fluphenazine: double-blind placebo trial. Br Med J 1973; 1:633–637Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Wistedt B, Palmstierna T: Depressive symptoms in chronic schizophrenic patients after withdrawal of long-acting neuroleptics. J Clin Psychiatry 1983; 44:369–371Medline, Google Scholar

49. Hogarty GE, Munetz MR: Pharmacogenic depression among outpatient schizophrenic patients: a failure to substantiate. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1984; 4:17–24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Roy A: Do neuroleptics cause depression? Biol Psychiatry 1984; 19:777–781Google Scholar

51. Berrios GE, Bulbena A: Post psychotic depression: the Fulbourn cohort. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1987; 76:89–93Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Siris SG, Strahan A, Mandeli J, Cooper TB, Casey E: Fluphenazine decanoate dose and severity of depression in patients with post-psychotic depression. Schizophr Res 1988; 1:31–35Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Barnes TR, Curson DA, Liddle PF, Patel M: The nature and prevalence of depression in chronic schizophrenic in-patients. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 154:486–491Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Bandelow B, Muller P, Gaebel WE: Depressive syndromes in schizophrenic patients after discharge from hospital. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1991; 240:113–120Crossref, Google Scholar

55. Davis KL, Kahn RS, Ko G, Davidson M: Dopamine in schizophrenia: a review and reconceptualization. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1474–1486Google Scholar

56. Rifkin A, Quitkin F, Klein DF: Akinesia: a poorly recognized drug-induced extrapyramidal behavioral disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1975; 32:672–674Crossref, Google Scholar

57. Rifkin A, Quitkin F, Kane JM, Klein DF: Are prophylactic antiparkinson drugs necessary? Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:483–489Google Scholar

58. Van Putten T, May PRA: “Akinetic depression” in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:1101–1107Google Scholar

59. Van Putten T: The many faces of akathisia. Compr Psychiatry 1975; 16:43–47Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Halstead SM, Barnes TRE, Speller JC: Akathisia: prevalence and associated dysphoria in an in-patient population with chronic schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 164:177–183Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Shear K, Frances A, Weiden P: Suicide associated with akathisia and depot fluphenazine treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1983; 3:235–236Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62. Drake RE, Ehrlich J: Suicide attempts associated with akathisia. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:499–501Link, Google Scholar

63. Liddle PF, Barnes TRE, Curson DA, Patel M: Depression and the experience of psychological deficits in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993; 88:243–247Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Lysaker PH, Bell MD, Bioty SM, Zito WS: The frequency of associations between positive and negative symptoms and dysphoria in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry 1995; 36:113–117Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65. Frank JD: Persuasion and Healing. Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press, 1973Google Scholar

66. Klein DF: Endogenomorphic depression: a conceptual and terminological revision. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974; 31:447–454Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67. deFigueiredo JM: Depression and demoralization: phenomenologic differences and research perspectives. Compr Psychiatry 1993; 34:308–311Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

68. Docherty JP, van Kammen DP, Siris SG, Marder SR: Stages of onset of schizophrenic psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 1978; 135:420–426Link, Google Scholar

69. Herz MI, Melville C: Relapse in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1980; 137:801–805Link, Google Scholar

70. Subotnik KL, Nuechterlein KH: Prodromal signs and symptoms of schizophrenic relapse. J Abnorm Psychol 1988; 97:405–412Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71. Tollefson GD, Andersen SW, Tran PV: The course of depressive symptoms in predicting relapse in schizophrenia: a double-blind, randomized comparison of olanzapine and risperidone. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 46:365–373Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

72. Malla AK, Norman RMG: Prodromal symptoms in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 164:287–293Crossref, Google Scholar

73. Kasanin J: The acute schizoaffective psychoses. Am J Psychiatry 1933; 90:97–126Link, Google Scholar

74. Levitt JJ, Tsuang MT: The heterogeneity of schizoaffective disorder: implications for treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:926–936Link, Google Scholar

75. Coryell W, Keller M, Lavori P, Endicott J: Affective syndromes, psychotic features, and prognosis, I: depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:651–657Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

76. Taylor MA: Are schizophrenia and affective disorder related? a selective literature review. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:22–32Link, Google Scholar

77. Zubin J, Spring B: Vulnerability: a new view of schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol 1977; 86:103–126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

78. Nuechterlein KH, Dawson MD: A heuristic vulnerability/stress model of schizophrenic episodes. Schizophr Bull 1984; 10:300–312Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

79. Norman RMG, Malla AK: Correlation over time between dysphoric mood and symptomatology in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry 1994; 35:34–38Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

80. Sax KW, Strakowski SM, Keck PE, Upadhyaya VH, West SA, McElroy SL: Relationships among negative, positive, and depressive symptoms in schizophrenia and psychotic depression. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168:68–71Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

81. Siris SG, Bermanzohn PC, Mason SE, Shuwall MA: Maintenance imipramine therapy for secondary depression in schizophrenia: a controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:109–115Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

82. Peuskens J: Risperidone in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia: a multinational, multi-center, double-blind, parallel group study versus haloperidol. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:712–726Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

83. Tandon R, Harrigan E, Zorn SH: Ziprasidone: a novel antipsychotic with unique pharmacology and therapeutic potential. J Serotonin Res 1997; 4:159–177Google Scholar

84. Borison RL, Arvanitis LA, Miller BG: ICI 204,636, an atypical antipsychotic: efficacy and safety in a multicenter, placebo-controlled trial in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996; 16:158–169Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

85. Chouinard G, Jones B, Remington G, Bloom D, Addington D, MacEwan GW, Labelle A, Beauclair L, Arnott W: A Canadian multicenter placebo-controlled study of fixed doses of risperidone and haloperidol in the treatment of chronic schizophrenic patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1993; 13:25–40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

86. Marder SR, Meibach RC: Risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:825–835Link, Google Scholar

87. Seeger TF, Seymour PA, Schmidt AW, Zorn SH, Schulz DW, Lebel LA, McLean S, Guanowsky V, Howard HR, Lowe JA III, Heym J: Ziprasidone (CP-88,059): a new antipsychotic with combined dopamine and serotonin receptor antagonist activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1995; 275:101–113Medline, Google Scholar

88. Jones H: Risperidone: a review of its pharmacology and use in the treatment of schizophrenia. J Serotonin Res 1997; 4:17–28Google Scholar

89. Meltzer HY, Matsubara S, Lee JC: Classification of typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs on the basis of dopamine D1, D2 and serotonin2 pKi values. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1989; 25:238–246Google Scholar

90. Deutch AY, Moghaddam B, Innis RB, Krystal JH, Aghajanian GK, Bunney BS, Charney DS: Mechanisms of action of atypical antipsychotic drugs: implications for novel therapeutic strategies for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1991; 4:121–156Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

91. Beasley CM, Tollefson G, Tran P, Satterlee W, Sanger T, Hamilton S: Olanzapine versus placebo and haloperidol: acute phase results of the North American double-blind olanzapine trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 1996; 14:111–123Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

92. Buchanan RW: Clozapine: efficacy and safety. Schizophr Bull 1995; 21:579–591Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

93. Kane JM, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H: Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic: a double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:789–796Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

94. Möller HJ, Muller H, Borison R, Schooler NR, Chouinard G: A path analytical approach to differentiate between direct and indirect drug effects on negative symptoms in schizophrenic patients: a re-evaluation of the North American risperidone study. Eur Arch Clin Neurosci 1995; 245:45–49Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

95. Tollefson GD, Beasley CM Jr, Tran PV, Street JS, Krueger JA, Tamura RN, Graffeo KA, Thieme ME: Olanzapine versus haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective and schizophreniform disorders: results of an international collaborative trial. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:457–465Link, Google Scholar

96. Tollefson GD, Sanger TM: Negative symptoms: a path analytic approach to a double-blind, placebo- and haloperidol-controlled clinical trial with olanzapine. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:466–474Link, Google Scholar

97. Franz M, Lis S, Pluddemann K, Gallhofer B: Conventional versus atypical neuroleptics: subjective quality of life in schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170:422–425Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

98. Tollefson GD, Andersen SW: Should we consider mood disturbance in schizophrenia as an important determinant of quality of life? J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60(suppl 5):23–29Google Scholar

99. Weaver MG: Olanzapine—pharmacology and clinical evaluation of a new atypical antipsychotic. J Serotonin Res 1997; 4:145–157Google Scholar

100. Rosenheck R, Cramer J, Xu W, Thomas J, Henderson W, Frisman L, Fye C, Charney D: A comparison of clozapine and haloperidol in hospitalized patients with refractory schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:809–815Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

101. Song F: Risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychopharmacol 1997; 11:65–71Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

102. Naber D: Subjective experiences of schizophrenic patients treated with antipsychotic medication. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1998; 13(suppl 1):S41–S45Google Scholar

103. Casey DE: Side effect profiles of new antipsychotic agents. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 11):40–45Google Scholar

104. Azorin JM: Long-term treatment of mood disorders in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1995; 91:20–23Crossref, Google Scholar

105. Ceskova E, Svestka J: Double-blind comparison of risperidone and haloperidol in schizophrenic and schizoaffective psychoses. Pharmacopsychiatry 1993; 26:121–124Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

106. Tran PV, Hamilton SH, Kuntz AJ, Potvin JH, Andersen SW, Beasley C, Tollefson GD: Double-blind comparison of olanzapine versus risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 17:407–418Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

107. Tollefson GD, Sanger TM, Lu Y, Thieme ME: Depressive signs and symptoms in schizophrenia: a prospective blinded trial of olanzapine and haloperidol. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:250–258Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

108. Tollefson GD, Sanger TM, Beasley CM, Tran PV: A double-blind, controlled comparison of the novel antipsychotic olanzapine versus haloperidol or placebo on anxious and depressive symptoms accompanying schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 43:803–810Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

109. Keck P, Buffenstein A, Ferguson J, Feighner J, Jaffe W, Harrigan EP, Morrissey MR: Ziprasidone 40 and 120 mg/day in the acute exacerbation of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: a 4-week placebo-controlled trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998; 140:173–184Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

110. Daniel DG, Zimbroff DL, Potkin SG, Reeves KR, Harrigan EP, Lakshminarayanan M (Ziprasidone Study Group): Ziprasidone 80 mg/day and 160 mg/day in the acute exacerbation of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: a 6-week placebo-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 1999; 20:491–505Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

111. Meltzer HY, Okayli G: Reduction of suicidality during clozapine treatment of neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia: impact on risk-benefit assessment. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:183–190Link, Google Scholar

112. Walker AM, Lanza LL, Arellano F, Rothman KJ: Mortality in current and former users of clozapine. Epidemiology 1998; 8:671–679Crossref, Google Scholar

113. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987; 13:261–276Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

114. Montgomery SA, Åsberg M: A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 134:382–389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

115. Klein DF: Psychiatric diagnosis and a typology of clinical drug effects. Psychopharmacologia 1968; 13:359–386Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

116. Robertson MM, Trimble MR: Major tranquilizers used as antidepressants: a review. J Affect Disord 1982; 4:173–193Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

117. Goldman RS, Tandon R, Liberzon I, Greden JF: Measurement of depression and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Psychopathology 1992; 25:49–56Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

118. Nelson JC: Treatment-Resistant Depression. Costa Mesa, Calif, PMA, 1987, pp 131–146Google Scholar

119. Mauri MC, Bravin S, Fabiano L, Vanni S, Boscati L, Invernizzi G: Depressive symptoms and schizophrenia: a psychopharmacological approach. Encephale 1995; 21:555–558Medline, Google Scholar

120. Jacobsen FM: Risperidone in the treatment of affective illness and obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:423–429Medline, Google Scholar

121. Zarate CA, Tohen M, Baldessarini RJ: Clozapine in severe mood disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:411–417Medline, Google Scholar

122. Hillert A, Maier W, Wetzel H, Benkert O: Risperidone in the treatment of disorders with a combined psychotic and depressive syndrome—a functional approach. Pharmacopsychiatry 1992; 25:213–217Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

123. Keck PE, Wilson DR, Strakowski SM, McElroy SL, Kizer DL, Balistreri TM, Holtman HM, DePriest M: Clinical predictors of acute risperidone response in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and psychotic mood disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:466–470Medline, Google Scholar

124. Parsa MA, Ramirez LF, Loula EC, Meltzer HY: Effect of clozapine on psychotic depression and parkinsonism. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1991; 11:330–331Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

125. Ranjan R, Meltzer HY: Acute and long-term effectiveness of clozapine in treatment-resistant psychotic depression. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 40:253–258Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

126. Weisler RH, Ahearn EP, Davidson JR, Wallace CD: Adjunctive use of olanzapine in mood disorders: five case reports. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1997; 9:259–262Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

127. Lindstrom E, von Knorring L: Changes in single symptoms and separate factors of the schizophrenic syndrome after treatment with risperidone or haloperidol. Pharmacopsychiatry 1994; 27:108–113Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

128. Marder SR, Davis JM, Chouinard G: The effects of risperidone on the five dimensions of schizophrenia derived by factor analysis: combined results of the North American trials. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:538–546Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

129. Young CR, Longhurst JG, Bowers M, Mazure C: The expanding indications for clozapine. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 5:216–234Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

130. Waddington JL, Scully PJ, O’Callighan E: The new antipsychotics, and their potential for early intervention in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1997; 28:207–222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

131. Pandey GN, Pandey SC, Janicak PG, Marks RC, Davis JM: Platelet serotonin-2 receptor binding sites in depression and suicide. Biol Psychiatry 1990; 28:215–222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

132. Kahn RS, Davidson M: Serotonin, dopamine and their interactions in schizophrenia: an editorial. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993; 112(suppl 1):S1–S4Google Scholar

133. Fleischhacker WW, Roth SD, Kane JM: The pharmacologic treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1990; 10:12–21Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

134. Dilsaver SC, Coffman JA: Cholinergic hypothesis of depression: a reappraisal. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1989; 9:173–179Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

135. Tandon R, Greden JF: Cholinergic hyperactivity and negative schizophrenic symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:745–753Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

136. Siris SG, Morgan V, Fagerstrom R, Rifkin A, Cooper TB: Adjunctive imipramine in the treatment of post-psychotic depression: a controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:533–539Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

137. Hogarty GE, McEvoy JP, Ulrich RF, DiBarry AL, Bartone P, Cooley S, Hammill K, Carter M, Munetz MR, Perel J: Pharmacotherapy of impaired affect in recovering schizophrenic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:29–41Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

138. Plasky P: Antidepressant usage in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1991; 17:649–657Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

139. Levinson DF, Umapathy C, Musthaq M: Treatment of schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia with mood symptoms. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1138–1148Google Scholar

140. Goff DC, Brotman AW, Waltes M, McCormick S: Trial of fluoxetine added to neuroleptics for treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:492–494Link, Google Scholar

141. Evins AE, Goff DC: Adjunctive antidepressant drug therapies in the treatment of negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Drug Therapy 1996; 6:130–147Google Scholar

142. Brenner R, Shopsin B: The use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1980; 15:633–647Medline, Google Scholar

143. Silver H, Nassar A: Fluvoxamine improves negative symptoms in treated chronic schizophrenia: an add-on double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry 1992; 31:698–704Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

144. Spina E, DeDomenico P, Ruello C, Longobardo N, Gitto C, Ancione M, DiRosa AE, Caputi AP: Adjunctive fluoxetine in the treatment of negative symptoms in chronic schizophrenic patients. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1994; 9:281–285Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

145. Goff DC, Midha KK, Sarid-Segal O, Hubbard JW, Amico E: A placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine added to neuroleptic in patients with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995; 117:417–423Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

146. Salokangas RKR, Saarijarvi S, Taiminen T, Kallioniemi H, Lehto H, Niemi H, Tuominen J, Ahola V, Syvalahti E: Citalopram as an adjuvant in chronic schizophrenia: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996; 94:175–180Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

147. Silver H, Shmugliakov N: Augmentation with fluvoxamine but not maprotiline improves negative symptoms in treated schizophrenia: evidence for a specific serotonergic effect from a double-blind study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1998; 18:208–211Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

148. Bucci L: The negative symptoms of schizophrenia and the monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1987; 91:104–108Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

149. Bodkin AJ, Cohen BM, Salomon MS, Cannon SE, Zornberg GL, Cole JO: Treatment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder by selegiline augmentation of antipsychotic medication. J Nerv Ment Dis 1996; 184:295–301Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

150. Perenyi A, Goswami U, Frecska E, Arato M: l-Deprenyl in treating negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 1992; 42:189–191Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

151. Decina P, Mukherjee S, Bocola V, Saraceni F, Hadjichristos C, Scapicchio P: Adjunctive trazodone in the treatment of negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1994; 45:1220–1223Google Scholar

152. Christison GW, Kirch DG, Wyatt RJ: When symptoms persist: choosing among alternative somatic treatments for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1991; 17:217–240Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

153. Lerner Y, Mintzer Y, Schestatzky M: Lithium combined with haloperidol in schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 153:359–362Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

154. Atre-Vaidya N, Taylor MA: Effectiveness of lithium in schizophrenia: do we really have an answer? J Clin Psychiatry 1989; 50:170–173Google Scholar

155. Hogarty GE, Anderson CM, Reiss DJ, Kornblith SJ, Greenwald DP, Javna CD, Madonia MJ: Family psychoeducational, social skills training, and maintenance chemotherapy in the aftercare treatment of schizophrenia, 1: one-year effects of a controlled study on relapse and expressed emotion. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:633–642Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar