Effects of Gonadal Steroids in Women With a History of Postpartum Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Endocrine factors are purported to play a role in the etiology of postpartum depression, but direct evidence for this role is lacking. The authors investigated the possible role of changes in gonadal steroid levels in postpartum depression by simulating two hormonal conditions related to pregnancy and parturition in euthymic women with and without a history of postpartum depression.METHOD: The supraphysiologic gonadal steroid levels of pregnancy and withdrawal from these high levels to a hypogonadal state were simulated by inducing hypogonadism in euthymic women—eight with and eight without a history of postpartum depression—with the gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist leuprolide acetate, adding back supraphysiologic doses of estradiol and progesterone for 8 weeks, and then withdrawing both steroids under double-blind conditions. Outcome measures were daily symptom self-ratings and standardized subjective and objective cross-sectional mood rating scales.RESULTS: Five of the eight women with a history of postpartum depression (62.5%) and none of the eight women in the comparison group developed significant mood symptoms during the withdrawal period. Analysis of variance with repeated measures of daily and cross-sectional ratings of mood showed significant phase-by-group effects. These effects reflected significant increases in depressive symptoms in women with a history of postpartum depression but not in the comparison group after hormone withdrawal (and during the end of the hormone replacement phase), compared with baseline.CONCLUSIONS: The data provide direct evidence in support of the involvement of the reproductive hormones estrogen and progesterone in the development of postpartum depression in a subgroup of women. Further, they suggest that women with a history of postpartum depression are differentially sensitive to mood-destabilizing effects of gonadal steroids.

Neither the phenomenology nor the prevalence of postpartum depression has been consistently demonstrated to be different from that of nonpuerperal depression. However, women who develop depression in the postpartum period are at a substantially increased risk for depression after subsequent pregnancies (1–5). These data imply that although a depressive episode during the postpartum period is not clinically distinct, it nonetheless appears to be triggered by some component of pregnancy, delivery, or the postpartum period in a subgroup of women. The hormonal events that characterize pregnancy and the postpartum period are obvious candidates for such a depression-triggering event; however, no consistent hormonal differences have been found in postpartum women with and without depression (6, 7), suggesting that women with postpartum depression have normal endocrine function.

Women with premenstrual syndrome (PMS) similarly have normal gonadal steroid levels and yet display a differential sensitivity to normal steroid levels such that their mood, but not that of women without PMS, is destabilized by normal changes in estrogen and progesterone levels (8). Consequently, we hypothesized that there may be a subgroup of women with a differential sensitivity to reproductive hormones in whom normal endocrine events related to childbirth could trigger a depressive episode. To test this hypothesis, we developed a model in which some of the hormonal events of pregnancy and childbirth are simulated in a scaled-down fashion, and using this model, we studied the effect of gonadal steroid manipulations on mood and behavior in women with and without a history of postpartum depression. In this study we asked two questions: 1) whether hormone withdrawal would precipitate symptoms in women with a history of postpartum depression but not in a comparison group of women without such a history, and 2) whether marked elevations in gonadal steroid levels during hormone addback would be associated with mood destabilization in women with a history of postpartum depression.

Method

Subject Selection

Subjects selected for this study were healthy, euthymic, unmedicated (including oral contraceptives), 22–45-year-old women with regular menstrual cycles (range=24–32 days) who came to our clinic in response to advertisements in local newspapers and the hospital newsletter. All women had one or more biological children and were at least 1 year past their most recent childbirth. Subjects were screened over two menstrual cycles using a 6-point daily mood and behavior self-rating form (adapted from reference 9). Women who met criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder (DSM-IV) were excluded to avoid the confound that cyclical mood symptoms would introduce during baseline screening. Subjects also had a physical examination and routine laboratory tests to exclude medical illness. To diagnose past and present psychiatric illness, subjects were interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (10) and the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version (SADS-L) (11).

Subjects were divided into two groups. The postpartum depression group comprised women without a current or recent history (1 year) of psychiatric illness (i.e., they were currently euthymic) but with at least one past episode of postpartum major depression and no history of nonpuerperal depression. The diagnosis of postpartum depression was established on the basis of DSM-IV criteria, which include the requirement that the onset of the episode of depression occurred within 4 weeks postpartum. Women with a history of a severe postpartum depression characterized by suicidal ideation or psychosis were excluded from the study to minimize the risk to which subjects were exposed. The comparison group comprised women with no history of past or present psychiatric illness. The study was approved by the NIMH intramural research panel. After complete description of the study to the subjects, oral and written informed consent were obtained.

Design

Baseline

Subjects provided daily and cross-sectional ratings for 2 months before receiving any medication, as described below. After this baseline, subjects received the first of five monthly injections with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog (leuprolide acetate, 3.75 mg/month), administered to produce a stable hypogonadal condition. Leuprolide was initially administered by day 6 of the subjects’ first menstrual cycle after the baseline period and subsequently at monthly intervals. The consequent suppressed and stabilized gonadal steroid levels allowed for a predictable steady state during the addback phase of the study and for hypogonadal levels during the subsequent withdrawal phase. Subjects also received active medication (described below) and/or placebo in a pre-prepared pill box every 2 weeks throughout the study. The number of tablets prescribed was adjusted biweekly on a random basis during baseline and according to plasma hormone levels during active treatment.

Addback

After 1 month of leuprolide and placebo tablets, high plasma levels of estradiol and progesterone were obtained by substituting micronized progesterone and estradiol for placebo for 8 weeks. Estradiol was started at a dose of 4 mg/day (two 2-mg tablets) and increased progressively up to 10 mg/day in three divided doses. Progesterone was started at 400 mg/day p.o. (four 100-mg tablets) in three divided doses and increased progressively according to plasma levels (target level=about 50 ng/ml, range=400–900 mg/day). Placebo tablets were used to supplement doses so that the number of tablets ingested was the same throughout the study.

Withdrawal phase and follow-up

Active medications were replaced with placebo, inducing a precipitous drop in plasma estradiol and progesterone levels. Hypogonadal levels were maintained for the 4-week withdrawal phase by leuprolide. Subsequently, women were followed for 8 more weeks while unmedicated.

To ensure that the subjects were kept blind to the contents of the tablets, the following measures were taken. First, active and placebo medications were identically packaged. Second, the number of ingested tablets taken daily was the same throughout the study. Third, subjects were informed that they could be placed on 8 weeks of active hormones at any time during the 16 weeks on tablets; however, in practice they all received the active medication after 4 weeks of placebo. Fourth, to prevent interpretation of spotting/bleeding as a “withdrawal bleed,” subjects were told that this phenomenon could occur at any time throughout the study. Fifth, the research nurses managing the subjects and raters were blind to the medications and study design, and doses were determined by the managing physician (M.B.), who was not directly involved in the routine interactions with or ratings of the subjects.

Psychometric Assessment

Throughout the study, subjects assessed their mood, behavioral symptoms, and hot flushes with daily self-ratings (9). In addition, the two standardized self-ratings were administered at each bimonthly clinic visit: the Beck Depression Inventory (12) and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (13). A standardized objective measure, the modified Cornell Dysthymia Scale (14), also was administered bimonthly by a nurse who was not directly involved in the study and who was blind to both the subject’s psychiatric history and to the phase of the study.

Statistical Analysis

Four 1-month periods were selected for analysis: the last 4 weeks of the screening period (baseline), weeks 4–8 of addback, weeks 1–4 after withdrawal, and weeks 9–12 after withdrawal (late follow-up phase). Outcome measures for analysis included the average of the four weekly mean scores for the daily self-ratings and the two bimonthly scores for the Beck Depression Inventory, the Cornell Dysthymia Scale, and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale over the four study periods. Five individual symptoms best reflecting clinical course—sadness, anxiety, mood lability, irritability, and anhedonia—were selected from the daily self-rating forms for analysis. As a measure of maximum distress, the scores for each of the five symptoms were averaged each week, and then a mean was calculated by using the weekly mean scores for the two symptoms with the highest weekly means (high daily symptom mean).

Analysis of variance with repeated measures (ANOVA)—with diagnosis (history of postpartum depression versus comparison group) as the between-subjects variable and phase (baseline, addback, withdrawal, late follow-up) as the within-subjects variable—was performed to test the two main study hypotheses. The primary hypothesis was whether hormone withdrawal would precipitate symptoms in women with a history of postpartum depression but not the comparison group. The secondary hypothesis was whether marked elevations in gonadal steroid levels during addback would be associated with mood destabilization in women with a history of postpartum depression. Significant findings on the repeated measures ANOVA were pursued with post hoc Bonferroni t tests. In addition, a repeated measures ANOVA, with the change in symptom severity from baseline as the dependent measure, was performed. The relationship between plasma hormone levels and mood changes was evaluated by using Pearson’s product moment correlation coefficients. Clinically significant symptom appearance was defined as an increase from baseline in the Cornell Dysthymia Scale of ≥12 points, which represents two standard deviations for the average baseline Cornell Dysthymia Scale score. Comparison of the proportion of women who developed significant symptoms across groups was performed with Fisher’s exact test.

Plasma Hormone Levels

Plasma estradiol and progesterone levels were determined by direct radioimmunoassay. Interassay coefficients of variation for estradiol and progesterone were 10% and 14%, respectively.

Results

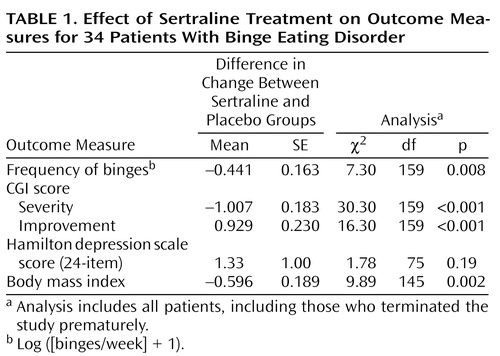

Sixteen women completed the study, eight with a history of postpartum depression (but no nonpuerperal affective disorder) and eight comparison subjects without a psychiatric history. One additional woman dropped out of the study during the initial stages consequent to intolerance of the required phlebotomies. Mean age for those with or without a history of postpartum depression was 33.5 years (SD=7.8) and 33.5 years (SD=4.9), respectively, and mean parity was 2.5 (SD=2.1) and 3.5 (SD=0.7), respectively. A comparison of symptom ratings during baseline, addback, withdrawal, and follow-up with repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant effects of group and phase for both the standardized and daily self-rating measures (>Table 1). On post hoc testing with Bonferroni t tests these effects were seen to reflect a significant increase in symptom severity in women with a history of postpartum depression, compared to those without such a history, in all but one measure during withdrawal and in all but two during addback (>Table 1 and Figure 1). Similarly, ratings for the women with a history of postpartum depression but not for the comparison group were significantly greater during withdrawal and, less robustly, during addback, compared with baseline (>Table 1). Although no significant differences in ratings between women with and without a history of postpartum depression were observed at baseline or during follow-up, elevated baseline ratings in three of eight subjects with a history of postpartum depression led us to perform a repeated measures ANOVA to analyze the change in ratings from baseline. Significant effects for group and phase identical to those described above were observed (F=10.4, df=2, 28, p<0.0001 for scores on the Cornell Dysthymia Scale). Finally, five of the eight women with a history of postpartum depression (62.5%) and none of the eight women in the comparison group developed clinically significant affective symptoms during the withdrawal phase (p=0.03, Fisher’s exact test).

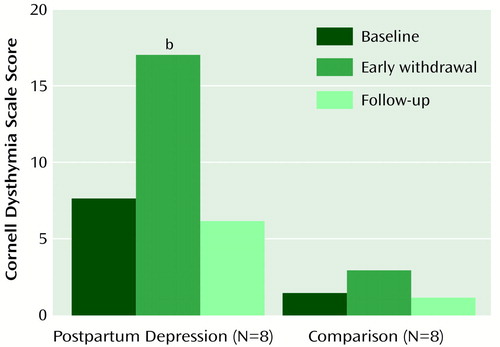

Although the severity of symptoms experienced by the five women who developed significant symptoms was less than they remembered having had during their episodes of postpartum depression (and only three had an Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score >10) (15), the quality and constellation of symptoms were often very similar. In addition to predominantly depressive symptoms, one of these five women also had mild hypomanic symptoms characterized by irritability, hyperactivity, hypervigilance, decreased need for sleep, and hypersexuality. Figure 2 illustrates the observed pattern of symptom development for a representative woman with a history of postpartum depression. The example shows a dramatic increase in depressive symptoms during the first 4 weeks of withdrawal and spontaneous subsequent improvement coincident with returning ovarian function.

Elevated plasma levels of estradiol and progesterone were sustained during the addback phase without significant differences between groups (estradiol mean=258 pg/ml, SD=103, and mean=298 pg/ml, SD=75, and progesterone mean=62 ng/ml, SD=64, and mean=66, ng/ml, SD=36, for women with a history of postpartum depression and the comparison group, respectively). Similarly, no group differences were identified in the plasma estradiol or progesterone levels during the withdrawal (hypogonadal) phase (estradiol mean=28.8 pg/ml, SD=15.9, and mean=25.9 pg/ml, SD=24.4, and progesterone mean=0.5 ng/ml, SD=0.1, and mean=0.4 ng/ml, SD=0.0, for women with a history of postpartum depression and the comparison group, respectively). The ANOVA diagnosis effect and the effect for diagnosis and phase were nonsignificant for both hormones. Gonadal steroid concentrations in the hypogonadal range were observed after withdrawal in all subjects, with no evidence of ovulation (based on plasma progesterone levels > 2 ng/ml) until 8–10 weeks after withdrawal. Although some subjects remained hypogonadal during weeks 5–8 after the last leuprolide injection, all subjects showed return of gonadal steroid production during the follow-up phase (weeks 9–12).

For all subjects, no significant correlation was found between plasma progesterone or estradiol levels during the end of the addback phase and either scores on the Cornell Dysthymia Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, and Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale or daily ratings during the addback or withdrawal phases.

Throughout the active study period most women had sporadic spotting usually lasting for a few days but occasionally lasting longer. None of the women experienced bleeding only during the withdrawal month, which could have otherwise compromised the blind study condition.

All subjects had some hot flushes during the first 8 weeks of withdrawal. However, in all cases, the emergence of mood symptoms during the withdrawal month preceded the onset of hot flushes.

Discussion

The significant increase in depressive symptoms during the withdrawal phase in the postpartum depression group but not in the comparison group suggests that women with a history of postpartum depression have a differential response to abrupt reduction of plasma levels of gonadal steroids, compared with women without a history of postpartum depression. The women with a history of postpartum depression participating in the study were asymptomatic and at least 1 year removed from their depression, suggesting that the behavioral sensitivity to perturbed gonadal steroid levels is a trait phenomenon. This interpretation is consistent with a study by Cooper and Murray (16) showing that women with postpartum depression and no antecedent affective disorder have a higher rate of subsequent postpartum depression episodes, but a lower risk for subsequent nonpuerperal depressive episodes, compared with women with nonpuerperal depression.

In this study, women with postpartum depression (but not the comparison group) showed increased symptoms in the addback phase with a peak during the withdrawal phase. These findings have both phenomenologic and mechanistic implications. First, our observation of mood destabilization during sustained elevation of gonadal steroids (as well as during withdrawal) is consistent with reports that depressive symptoms are more common during pregnancy and may predict postpartum depression in some women (4, 17–21). In fact, Stowe et al. (personal communication, 1999) observed that 45 of 48 women with a history of postpartum depression developed depressive symptoms during subsequent pregnancies. Thus the onset of depression before rather than after parturition may be the rule rather than the exception in postpartum depression. Second, although symptoms of postpartum depression may in some cases start during pregnancy, the withdrawal from supraphysiologic concentrations of gonadal steroids that accompanies delivery may precipitate a worsening or the development of new symptoms in some women. The design of this study cannot distinguish between the effects of withdrawal and hypogonadism. Nonetheless, the proximity of symptoms to the actual withdrawal from the gonadal steroids and the improvement of symptoms in women with a history of postpartum depression during the month after withdrawal when still relatively hypogonadal suggest that the postpartum hypogonadism per se is not of primary importance as a trigger of depression. These findings also suggest that the reported efficacy of estrogen in treating (22) or preventing the recurrence (23) of postpartum depression results from the prevention of the sudden postpartum withdrawal of estrogen.

This study did not fully replicate the reproductive endocrine events that occur during pregnancy and the postpartum. Within 1–3 days of delivery circulating plasma estradiol and progesterone drop from concentrations of about 15,000 pg/ml and 150 ng/ml, respectively, to hypogonadal levels. Although the high levels of plasma estradiol and progesterone in this study were sustained for at least 6 weeks, both the levels and duration of exposure were substantially less than those achieved during pregnancy. Nonetheless, related studies suggest that significant adverse mood reactions may be induced by levels and changes in gonadal steroids that are considerably more modest than those created in this study (8, 24).

Several mechanisms may underlie the depressive symptoms observed in this study. Gonadal steroids function as major neuromodulators, profoundly altering the activity of central nervous system neurotransmitter systems implicated in mood regulation and mood disorders (25, 26). Given the neuromodulatory effects of gonadal steroids and the absence of abnormal hormone levels in women with postpartum depression (6), postpartum depression could represent either a homeostasis deficiency—i.e., a failure to compensate for neuroregulatory changes induced by major (but normal) perturbations of gonadal steroid levels—or an amplification or modification of an intracellular steroid signal.

Despite the small group sizes in this study, significant effects of group and phase were seen, reflecting the intensity of the symptoms elicited in the postpartum depression group and the lack of symptoms in the comparison group. A possible confound in this analysis was the slightly elevated baseline mean mood rating in the women with a history of postpartum depression (three of them had premenstrual mood symptoms during the baseline cycles despite failing to meet DSM-IV criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder during screening). Reanalysis of data with change in symptom severity from baseline rather than mean severity scores did not alter the results.

The possibility that the blind study condition was broken for the subjects by the occurrence of either hot flushes, side effects, or spotting during the study is highly unlikely, because none of these factors was exclusively associated with a particular study phase or group. Furthermore, when asked at the end of the study to guess when they were withdrawn from the hormones, the only clue identified by subjects was the presence or absence of mood symptoms (three of the women with a history of postpartum depression and none of the women in the comparison group guessed correctly).

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that women with a history of postpartum depression may have a differential sensitivity to changing levels of the gonadal steroids estradiol and progesterone. This sensitivity appears to be a trait vulnerability that is not present in women without a history of postpartum depression. These data provide the first direct evidence in support of the pathophysiologic relevance of the reproductive hormones estrogen and progesterone in the onset of postpartum depression episodes. Identification of factors causing this differential responsivity to gonadal steroids will improve our understanding of postpartum depression.

|

Received April 26, 1999; revision received Nov. 19, 1999; accepted Jan 6, 2000. From the Behavioral Endocrinology Branch, NIMH; the Developmental Endocrinology Branch, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH; and the Clinical Center Nursing Department, NIH. Address reprint requests to Dr. Rubinow, NIMH, Bldg. 10, Room 3N238, 10 Center Drive, MSC 1276, Bethesda, MD 20892-1276; [email protected] (e-mail). Micronized progesterone was supplied by Women’s Health Pharmacy, Madison, Wisc., and micronized estradiol was supplied by Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Princeton, N.J.

Figure 1. Mean Scores on the Cornell Dysthymia Scale Before and After Estrogen and Progesterone Replacement in Eight Women With a History of Postpartum Depression and Eight Normal Comparison Womena

aStudy phases: 8-week baseline, when no medications were administered; 4-week early withdrawal, when estradiol and progesterone, previously administered during an 8-week addback period, were withdrawn; and 8-week follow-up, when no medications were administered.

bSignificant difference between baseline and withdrawal periods in the group with a history of postpartum depression (Bonferroni post hoc t test, p<0.01).

Figure 2. Mean Scores on the Cornell Dysthymia Scale at Baseline, After Addback and Withdrawal of Estrogen and Progesterone Replacement, and During Follow-Up for a Representative Woman With a History of Postpartum Depressiona

aStudy phases: 8-week baseline, when no medications were administered; 8-week addback, when estradiol and progesterone were administered; 4-week withdrawal, when estradiol and progesterone were withdrawn; and 8-week follow-up, when no medications were administered. The shaded area corresponds to the 4-week withdrawal period. The horizontal scale represents 2-week intervals; the representation of the baseline and addback phases is compressed, with 6 weeks separating the baseline rating and the first rating during the addback phase.

1. Kumar R, Robson KM: A prospective study of emotional disorders in childbearing women. Br J Psychiatry 1984; 144:35–47Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Cox JL, Murray D, Chapman G: A controlled study of the onset, duration and prevalence of postnatal depression. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 163:27–31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kendell RE, Chalmers JC, Platz C: Epidemiology of puerperal psychoses. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 150:662–673Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. O’Hara MW, Zekowski EM, Philipps LH, Wright EJ: Controlled prospective study of postpartum mood disorders: comparison of childbearing and nonchildbearing women. J Abnorm Psychol 1990; 99:3–15Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Cooper PJ, Campbell EA, Day A, Kennerley H, Bond A: Non-psychotic psychiatric disorder after childbirth: a prospective study of prevalence, incidence, course and nature. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 152:799–806Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Wieck A: Endocrine aspects of postnatal mental disorders. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol 1989; 3:857–877Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Harris B: Biological and hormonal aspects of postpartum depressed mood: working towards strategies for prophylaxis and treatment. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 164:288–292Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Schmidt PJ, Nieman LK, Danaceau MA, Adams LF, Rubinow DR: Differential behavioral effects of gonadal steroids in women with and in those without premenstrual syndrome. N Engl J Med 1998; 338:209–216Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Endicott J, Nee J, Cohen J, Halbreich U: Premenstrual changes: patterns and correlates of daily ratings. J Affect Disord 1986; 10:127–135Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P), version 2. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

11. Spitzer RL, Endicott J: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version, 3rd ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1979Google Scholar

12. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R: Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1991; 150:782–786Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Mason BJ, Kocsis JH, Leon AC, Thompson S, Frances AJ, Morgan RO, Parides MK: Measurement of severity and treatment response in dysthymia. Psychiatr Ann 1993; 23:625–631Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Areias MEG, Kumar R, Barros H, Figueiredo E: Comparative incidence of depression in women and men, during pregnancy and after childbirth validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in Portuguese mothers. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 169:30–35Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Cooper PJ, Murray L: Course and recurrence of postnatal depression: evidence for the specificity of the diagnostic concept. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:191–195Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. O’Hara MW, Schlechte JA, Lewis DA, Varner MW: Controlled prospective study of postpartum mood disorders: psychological, environmental, and hormonal variables. J Abnorm Psychol 1991; 100:63–73Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Hobfoll SE, Ritter C, Lavin J, Hulsizer MR, Cameron RP: Depression prevalence and incidence among inner-city pregnant and postpartum women. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995; 63:445–453Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Pitt B: “Atypical” depression following childbirth. Br J Psychiatry 1968; 114:1325–1335Google Scholar

20. Dean C, Kendell RE: The symptomatology of puerperal illnesses. Br J Psychiatry 1981; 139:128–133Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Hannah P, Adams D, Lee A, Glover V, Sandler M: Links between early post-partum mood and post-natal depression. Br J Psychiatry 1992; 160:777–780Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Gregoire AJP, Kumar R, Everitt B, Henderson AF, Studd JWW: Transdermal oestrogen for treatment of severe postnatal depression. Lancet 1996; 347:930–933Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Sichel DA, Cohen LS, Robertson LM, Ruttenberg A, Rosenbaum JF: Prophylactic estrogen in recurrent postpartum affective disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1995; 38:814–818Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Magos AL, Brewster E, Singh R, O’Dowd T, Brincat M, Studd JWW: The effects of norethisterone in postmenopausal women on oestrogen replacement therapy: a model for the premenstrual syndrome. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1986; 93:1290–1296Google Scholar

25. Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ, Roca CA: Estrogen-serotonin interactions: implications for affective regulation. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 44:839–850Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Smith SS, Gong QH, Hsu F-C, Markowitz RS, ffrench-Mullen JMH, Li X: GABAA receptor alpha-4 subunit suppression prevents withdrawal properties of an endogenous steroid. Nature 1998; 392:926–930Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar