Open Trial of Psychodynamic Psychotherapy for Panic Disorder: A Pilot Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This report contains preliminary data from an open trial of brief psychodynamic psychotherapy for panic disorder. METHOD: Fourteen patients with primary DSM-IV panic disorder completed a 24-session, twice-weekly course of psychodynamic psychotherapy. Other psychiatric treatment was not permitted throughout the 12-week treatment period and the 6-month follow-up. Symptoms were assessed at baseline, treatment termination, and 6-month posttermination follow-up (40 weeks). RESULTS: Statistically significant, clinically meaningful improvements appeared in panic, depression, anxiety, and functional impairment both at treatment termination and at 6-month follow-up. CONCLUSIONS: Psychodynamic monotherapy can be used successfully to retain and treat patients with panic disorder. Psychodynamic interventions warrant further study for patients with panic disorder.

Panic disorder is a prevalent, chronic, and debilitating syndrome associated with high rates of utilization of medical and psychiatric services (1, 2). Several treatments, including pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavior therapy, have shown short-term efficacy for panic disorder. Long-term outcome data from these interventions are less clear (3, 4).

Psychodynamic psychotherapy has received sparse systematic study as treatment for specific psychiatric disorders. A randomized controlled trial (5) demonstrated that a 15-session, weekly, manualized psychodynamic psychotherapy combined with clomipramine reduced relapse over 18 months among panic disorder patients significantly more than did clomipramine alone. In another study (6), a non–cognitive behavior psychotherapy was as effective as cognitive behavior therapy. Some case reports (7) suggest the effectiveness of psychodynamic treatments for panic. On the basis of this literature and our experience, we developed a manual for panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy of panic disorder (8). We report the results for 14 patients with panic disorder who have now completed treatment based on this manual.

Method

Seventeen patients with DSM-IV panic disorder were recruited for participation. Fourteen patients met the criteria for a second current axis I disorder, including five with major depression. Three patients dropped out: two after session 2 (week 1) and one after session 14 (week 7). The 14 remaining patients were treated by using a 24-session, twice-weekly intervention. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The assessment measures included a structured diagnostic interview and symptom ratings by an independent rater using the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (9), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (10), and Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (11). The subjects completed a brief self-report measure of functional impairment, the Sheehan Disability Scale (12). The assessments occurred at baseline, after treatment termination (week 16), and at 6-month posttermination follow-up (week 40). Other psychiatric treatment was not permitted throughout the 12-week treatment period and the 6-month follow-up.

The principles of panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy emphasize unconscious thought, free association, and centrality of the transference. The therapist focuses on these processes as they relate to panic symptoms. Common themes of difficulty with separations and unconscious rage inform interpretive interventions.

To diminish acute panic symptoms, we hypothesize from a psychodynamic view the necessity of uncovering unconscious meanings of symptoms. The psychodynamic approach thus contrasts with the “atheoretical” and acontextual DSM definition of “out of the blue” panic disorder phenomena.

We hypothesize that to lessen the vulnerability to panic, core “dynamisms” must be understood and altered. Common psychodynamic conflicts in panic disorder involve difficulties with separation and independence, with recognition and management of anger, and with perceived dangers of sexual excitement. These dynamisms must be identified, often through their emergence in the transference.

The psychodynamic view hypothesizes that the experience of termination in this time-limited psychotherapy permits panic disorder patients to reexperience their severe difficulties with separation and autonomy directly with the therapist to articulate and understand underlying fantasies, rendering them less magical and frightening. Patient reaction to termination is aggressively addressed for at least the final eight sessions of treatment.

Six graduate psychoanalysts underwent a 16-week training course in panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy. All sessions were videotaped, and therapist adherence was monitored with an adherence protocol to ensure that core features of this treatment were delivered.

The Wilcoxon paired-rank sum test was used to compare the subjects’ symptoms and impairment before and after treatment. Within-group effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were computed to correspond with each Wilcoxon paired-rank sum test. The intent-to-treat strategy was employed and used the last observation carried forward. The comparison of outcome at week 16 with the outcome at follow-up excluded the subjects without week 16 assessments. Inferential tests were not used to compare the dropouts (N=3) and completers (N=14) because of limited statistical power.

Results

The 17 study entrants had a mean age of 31 years (SD=7); 11 were women, and six were men. Twelve were white, four were African American, and one was Asian. Seven were married, eight were single, one was separated, and one was divorced. Sixteen were employed. Besides DSM-IV panic disorder, 15 had agoraphobia. All had been medication free for 4 weeks before the baseline assessments.

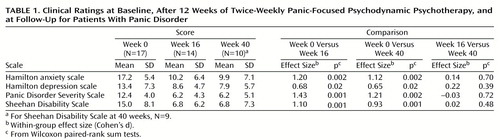

Of the 14 treatment completers, 13 showed remission of panic, defined as a reduction from baseline of more than 50% in the score on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale and maintenance of a panic-free state for 3 weeks. Of the 10 who have thus far reached the 40-week follow-up, nine have sustained remission. Symptom scores and comparisons are shown in Table 1.

Discussion

The subjects treated with panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy in this open pilot project showed marked improvement in panic disorder symptoms, sustained over a 6-month treatment-free follow-up period. The effect size was large and no less than effect sizes for demonstrated efficacious treatments (13). We documented substantial improvement in scores on the Hamilton anxiety and depression scales and scores for functional impairment. Cognitive behavior therapy has demonstrated efficacy with one-half of the number of sessions used in this trial. It is not clear whether panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy would work at a lower dose or whether additional benefits accrue as a result of this more intensive intervention.

This study has several limitations. This was an open trial. None of the subjects, therapists, or raters was blinded to mode of treatment. The study group is too small to draw conclusions. Panic patients who were unable to stop taking medication were not enrolled. For eight of the 17 subjects who began the study, antipanic medication had been ineffective and was tapered off by the study team before the subjects entered the study. Data on the three dropout subjects were included in the analyses using the intent-to-treat principle. It is important to note that two of the dropouts could not sustain their medication-free state. It is not clear what benefit panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy might have for panic patients who require medication.

Panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy may be a promising treatment for panic disorder patients. It is also possible that combining panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy with medication would improve the long-term outcome of pharmacotherapy. A randomized controlled trial of panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy is needed to confirm its efficacy.

|

Received Oct. 26, 1999; revision received April 19, 2000; accepted May 12, 2000. From the Department of Psychiatry, Joan and Sanford I. Weill Medical College, Cornell University, and New York Presbyterian Hospital. Address reprint requests to Dr. Milrod, Department of Psychiatry, Joan and Sanford I. Weill Medical College, Cornell University/New York Presbyterian Hospital, 525 East 68th St., New York, NY 10021; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by the New York Community Trust through a fund established by DeWitt Wallace, by two grants from the American Psychoanalytic Association Fund for Psychoanalytic Research, and by William Frosch, M.D.

1. Markowitz JS, Weissman MM, Ouellette R, Lish JD, Klerman GL: Quality of life in panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:984–992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Rosenbaum JF: Panic disorder: making clinical sense of the latest research. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:127–134Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Milrod B, Busch F: The long-term outcome of treatments for panic disorder: a review of the literature. J Nerv Ment Dis 1996; 184:723–730Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Pollack MH, Smoller JW: The longitudinal course and outcome of panic disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1995; 18:785–801Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Wiborg IM, Dahl AA: Does brief dynamic psychotherapy reduce the relapse rate of panic disorder? Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:689–694Google Scholar

6. Shear MK, Pilkonis PA, Cloitre M, Leon AC: Cognitive behavioral treatment compared with nonprescriptive treatment of panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:395–401Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Milrod B, Shear MK: Dynamic treatment of panic disorder: a review. J Nerv Ment Dis 1991; 179:741–743Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Milrod B, Busch F, Cooper A, Shapiro T: A Manual for Panic-Focused Psychodynamic Psychotherapy. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997Google Scholar

9. Shear MK, Brown TA, Barlow DH, Money R, Sholomskas DE, Woods SW, Gorman JM, Papp LA: Multicenter collaborative Panic Disorder Severity Scale. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1571–1575Google Scholar

10. Hamilton M: The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1959; 32:50–55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Sheehan DV: The Sheehan Disability Scales, in The Anxiety Disease. New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1983, p 151Google Scholar

13. Penava SJ, Otto MW, Maki KM, Pollack MH: Rate of improvement during cognitive-behavioral group treatment for panic disorder. Behav Res Ther 1998; 36:665–673Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar