A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy for Panic Disorder

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to determine the efficacy of panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy relative to applied relaxation training, a credible psychotherapy comparison condition. Des- pite the widespread clinical use of psychodynamic psychotherapies, randomized controlled clinical trials evaluating such psychotherapies for axis I disorders have lagged. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first efficacy randomized controlled clinical trial of panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy, a manualized psychoanalytical psychotherapy for patients with DSM-IV panic disorder. Method: This was a randomized controlled clinical trial of subjects with primary DSM-IV panic disorder. Participants were recruited over 5 years in the New York City metropolitan area. Subjects were 49 adults ages 18–55 with primary DSM-IV panic disorder. All subjects received assigned treatment, panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy or applied relaxation training in twice-weekly sessions for 12 weeks. The Panic Disorder Severity Scale, rated by blinded independent evaluators, was the primary outcome measure. Results: Subjects in panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy had significantly greater reduction in severity of panic symptoms. Furthermore, those receiving panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy were significantly more likely to respond at treatment termination (73% versus 39%), using the Multicenter Panic Disorder Study response criteria. The secondary outcome, change in psychosocial functioning, mirrored these results. Conclusions: Despite the small cohort size of this trial, it has demonstrated preliminary efficacy of panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy for panic disorder.

Panic disorder is an ongoing public health problem. Patients with panic disorder report poor physical and emotional health, high prevalence of alcohol and substance abuse, and high prevalence of attempted suicide (1 , 2) . Medical costs are high for panic disorder: one-half of all primary care visits in the United States are precipitated by physical sensations associated with panic disorder, including dizziness, heart palpitations, chest pain, dyspnea, and abdominal pain (1) . Patients with panic disorder account for 20% of emergency room visits (2) and are 12.6 times as likely to visit emergency rooms as the general population (3) . Panic disorder patients have the highest rates of morbidity and health care utilization relative to patients with other psychiatric diagnoses and to patients without psychiatric diagnoses (4) .

Panic disorder impairs psychosocial functioning through high anxiety, somatic symptoms, restricted life style, increased incidence of comorbid psychiatric conditions, and high rates of suicide and untimely death (1 , 4 , 5) . Panic sufferers in the community have similar health and social consequences to people with major depression (3) .

Empirically-Supported Treatments for Panic Disorder

There has been substantial research progress in determining efficacious treatments for panic disorder. Pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) have shown efficacy for panic disorder (6 , 7) ; both have enduring effects (7 , 8) . Only a few trials have studied combinations of pharmacotherapy with psychotherapy for panic disorder, with mixed results (9 – 11) .

Panic treatment studies of all modalities report substantial proportions of patients (29%–48%) who do not respond to treatments of demonstrated efficacy (8 – 10) . Another meaningful proportion (25%–35% [ 2 , 12 – 14 ]) prematurely terminates treatment (9 , 10 , 12) . The need to test additional nonpharmacological treatments for panic disorder derives partly from the need to further investigate an understudied group of panic disorder patients: those who refuse medication or report exquisite sensitivity to side effects (13) . Research is also needed to test nonpharmacological alternatives for patients who do not respond to our current standard interventions.

Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy for Panic Disorder

Psychodynamic psychotherapy is a form of psychotherapy related to psychoanalysis; both treatments share common theoretical underpinnings. Nevertheless, psychodynamic psychotherapy is a distinct treatment. Panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy (15) is a brief, panic-focused psychodynamic intervention. Psychoanalytic psychotherapy has existed for more than a century, during which successful psychoanalytic treatments of patients with panic disorder have been reported (14) . One randomized controlled trial showed that 12 weekly sessions of psychodynamic psychotherapy significantly reduced relapse in panic disorder patients treated with clomipramine relative to clomipramine alone (11) .

We hypothesized that panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy for panic disorder would be more efficacious than the comparator, applied relaxation training (16) . Applied relaxation training is a behavioral therapy related to but less elaborate than CBT (the unpublished manual by JA Cerny et al. is available from Dr. Milrod upon request). This is the first time a psychodynamic treatment has undergone formal efficacy testing for any DSM-IV anxiety disorder, despite common clinical use (7 , 17) .

Method

This was a randomized controlled clinical trial of panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy and applied relaxation training for subjects with primary DSM-IV panic disorder with and without agoraphobia. Subjects were randomly assigned using a computer generated treatment assignment list that was stratified by presence or absence of 1) comorbid current DSM-IV major depression and 2) stable doses of antipanic medication. The trial was conducted between July 2000 and Jan. 2004 and approved by the Weill Medical College Institutional Review Board.

Subjects

To meet entrance criteria, subjects required diagnosis with primary DSM-IV panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, and a minimum severity score of 5 on the 0- to 8-point Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, Lifetime Version (18) , whether or not they were taking antipanic medication. Patients had a minimum of one weekly panic attack.

All subjects signed informed consent. Subjects meeting study entrance criteria while taking stable doses of medication agreed to keep medication type and dose constant throughout the study (total patients: N=9; applied relaxation training patients: N=4; panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy patients: N=5). Study psychiatrists prescribed such medication when present to ensure stability; all were on standard antipanic doses of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Patients discontinued ongoing psychotherapy to gain study entrance. Patients with comorbid major depression, personality disorders, and severe agoraphobia were included, making this cohort more symptomatic than in many prior panic disorder studies (9 – 11) , yet more representative of panic disorder as described in the clinical epidemiological literature (6 – 9) . Psychosis, bipolar disorder, and active substance abuse (6 months remission necessary) were exclusions.

Assessments

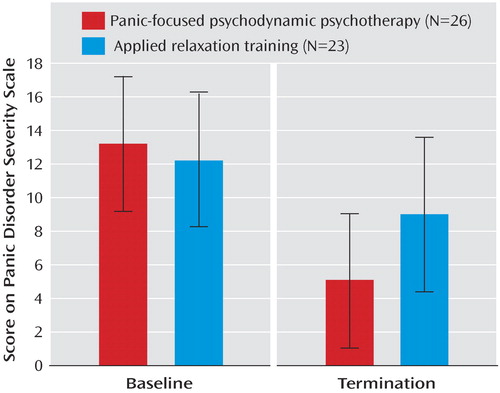

Independent evaluators, blinded to subject condition and therapist orientation, assessed subjects at baseline, treatment termination, and at 2, 4, 6, and 12 months posttreatment termination ( Figure 1 ). The primary outcome measure was the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (19) ( Figure 2 ), a clinician-administered instrument monitoring the number of panic attacks, limited symptom attacks, agoraphobic avoidance, and somatic sensitivity. The Panic Disorder Severity Scale was analyzed as a continuous measure, although the criterion for “response” that has become standard (9) —a 40% reduction from the baseline Panic Disorder Severity Scale score–is determined categorically. Other measures included the Sheehan Disability Scale (20) , a measure of psychosocial impairment; the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D); and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), a measure of nonpanic anxiety.

Training of Independent evaluators

Independent evaluators were trained for criterion on the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, Lifetime Version. All evaluators were master’s level diagnosticians with >35 hours training on the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, Lifetime Version and >12 hours of training on symptom scales. To evaluate rater drift and monitor interrater reliability, the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, Lifetime Version raters co-rated two subjects every 9 months. Interrater reliability of each assessment measure was examined using two independent raters (one of whom conducted the interview) for each of five subjects (Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, Lifetime Version, kappa=0.91; Panic Disorder Severity Scale, kappa=0.89).

Interventions

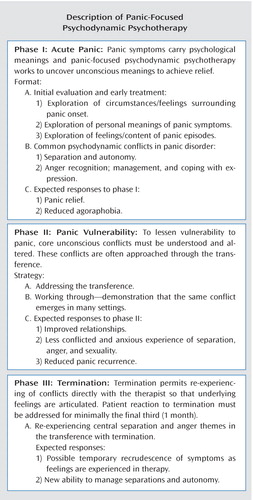

Panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy is a 24-session, twice-weekly (12 week), manualized psychoanalytic psychotherapy (1) . It showed promising preliminary outcome results in an open trial (23 , 24) . This therapy uses substantially different techniques than CBT (see Figure 1 for panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy description). There is no homework or exposure protocol in panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Applied relaxation training in this study is a 24-session, twice-weekly, manualized psychotherapy. Treatment starts with a three-session rationale and explanation about panic disorder. Applied relaxation training utilizes progressive muscle relaxation techniques and exposure. Progressive muscle relation training involves focusing attention on particular muscle groups, tensing the muscle group for 5–10 seconds, attending to sensations of tension, and relaxing the muscles. The training also involves therapist suggestions of deepening relaxation, attending to differences between sensations of tension and relaxation, and suggestions of deepening relaxation. The number of muscle groups is gradually reduced from 16 to eight to four. Discrimination training, generalization, relaxation by recall, and cue-controlled relaxation (pairing the relaxed state to the word “relax”) follow. One section addresses relaxation-induced panic.

Home practice is required twice daily. By week 6, subjects apply relaxation skills to anxiety situations in a graduated manner. Subjects learn to identify early stages of anxiety, to use relaxation as an active coping strategy whenever they become aware of tension, and to practice relaxation regularly throughout the day in various situations to maximize generalization. Applied relaxation training involves daily assigned homework and an exposure protocol.

Applied relaxation training has been used in five controlled trials (12) and demonstrated efficacy for panic disorder in one (16) . It has been found less efficacious than CBT in other studies (8 , 10 , 25) . Applied relaxation training is an active comparison treatment, controlling for therapist contact, expertise, and expectancy of improvement, potentially important threats to internal validity. Despite its being somewhat less potent than CBT, panic disorder patients find applied relaxation training credible and attractive. To our knowledge, no studies have found applied relaxation training less credible for panic disorder than alternatives such as CBT. In a study comparing CBT to applied relaxation training (16) , panic disorder patients rated applied relaxation training and CBT equally high on credibility and expectancy for improvement.

We chose to test panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy against a less active control psychotherapy in this first efficacy test rather than against the better established CBT for several reasons. In the first tests of new treatments, comparison treatments are preferable to empirically validated reference treatments (26 , 27) .

1) There are no well-established margins for testing equivalence in panic disorder, a sine qua non for equivalence studies (28) . The Food and Drug Administration’s Guidance Document (28 , 29) states: “In order to implement an equivalence or noninferiority trial, the magnitude [of medication] effect must be stable and well-established in the literature, with consistent results seen from one trial to the next” ( 28 , p.32). We have not yet reached this juncture in panic disorder studies. All researchers would agree that a 1-point Panic Disorder Severity Scale score difference is not clinically significant, but it is unclear whether panic researchers would agree on the significance of a 2- or 3-point difference in the Panic Disorder Severity Scale outcome. (As a frame of reference, the standard deviation at the end of the multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial study was 4.55.) Furthermore, the margin of equivalence must be substantially smaller than the hypothesized treatment effect that is used to determine cohort size in a superiority trial.

2) Even if the field had agreed on a margin of equivalence, the cohort size needed for an equivalence study would have exceeded that required by our study design.

Therapists

Panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy therapists (N=8)

Panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy therapist training comprised a 12-hour course. All panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy therapists were M.D. physicians who had completed psychiatric residency or Ph.D. psychologists, with specific training in panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy entailing a 12-hour course and a pilot supervised videotaped case as well as a minimum of 2 years of clinical experience treating panic disorder using psychodynamic psychotherapy. All had completed at least 3 years of psychoanalytic training at an institute. For panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy therapists, the mean amount of experience was 21 years (range: 2–40 [SD=8.6] years).

Applied relaxation training therapists (N=6)

Applied relaxation training therapists were M.D. physicians who had completed psychiatric residency or Ph.D. psychologists, with specific training in applied relaxation entailing a 6-hour course, a pilot supervised videotaped case, and a minimum of 2 years of clinical experience treating panic disorder patients with applied relaxation training and CBT. All applied relaxation training therapists had extensive CBT experience for panic disorder and used some form of relaxation training in their routine practice; two therapists used applied relaxation training routinely in practice. For applied relaxation training therapists, the mean experience was 16 years (range: 5–35 [SD=11.3] years) (Mann-Whitney: p=0.66 between therapist groups).

Ongoing Supervision

Therapists in both modalities met monthly for group supervision and received individual supervision as needed. Therapists in both modalities were monitored for adherence to treatment protocol by adherence raters in each modality with equal frequency. Three videotapes were rated for adherence per individual treatment. All therapists met predetermined adherence standards. For panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy therapists, the cutoff for acceptable adherence was a score of 4 out of 6 on at least five of seven items on the Panic-Focused Psychodynamic Psychotherapy Adherence Rating Scale (available from the authors). Four raters determined reliability by applying the Panic-Focused Psychodynamic Psychotherapy Adherence Scale to videotapes of panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy sessions. The mean interrater intraclass correlation was 0.92 (N=50). The average panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy therapist adherence was 5.5.

For applied relaxation training therapists, required scores were 5 out of 7 on all three items scored for the rated session on the Applied Relaxation Training Adherence Scale (unpublished instrument of MW Otto and MH Pollack available from Dr. Milrod upon request). All psychotherapy sessions were videotaped for adherence monitoring. Applied relaxation training adherence raters from Boston University assisted us with applied relaxation training adherence monitoring. Applied relaxation training therapists achieved an average adherence rating of 6.2 out of 7 points (tapes for each therapist, N=12).

Data Analytic Procedures

The analyses were conducted in accordance with the plans specified in the protocol. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the randomly assigned groups were compared using t tests for continuous variables and chi square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Efficacy was evaluated with t tests comparing groups on change from baseline for each primary and secondary efficacy measure. Response rates were compared using chi square tests. Secondary analyses involved a multiple linear regression analysis approach to analysis of covariance. Covariates included gender, baseline of the Panic Disorder Severity Scale, baseline of the Sheehan Disability Scale, depression, and dropout status. The assumption of no covariate by treatment interaction was evaluated for each covariate (30) . A two-tailed alpha level was used for each statistical test. Alpha was not adjusted for tests of efficacy because one primary dependent variable (Panic Disorder Severity Scale) was specified a priori . The intention-to-treat principle was employed by carrying the last observation forward, which by design was the baseline assessment for subjects who did not complete the study if they refused assessment at the time of dropout.

Results

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

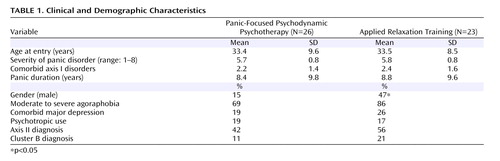

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort are presented in Table 1 . Subjects had a mean age of 33 years. Seventy-one percent were Caucasian, 27% African American, 2% Asian, and 18% reported Hispanic origin. The applied relaxation training group contained a significantly larger proportion of men than the panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy group (47% versus 15%, respectively [two-tailed Fisher’s exact, p=0.03]). There were no other significant demographic or clinical differences between the two treatment groups. Variables examined included the number of comorbid axis I diagnoses, duration of panic disorder, presence of moderate to severe agoraphobia, rates of comorbid major depression, presence of psychotropic medication (18% of subjects were receiving standard doses of SSRIs), presence of axis II comorbidity determined by SCID-II (31) , and specifically cluster B personality disorders.

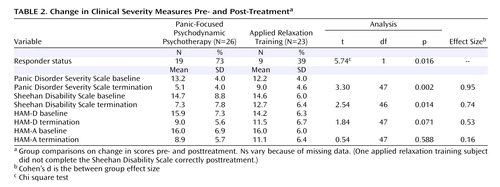

One important observation was that no significant baseline differences appeared between the randomly assigned groups in severity of panic disorder, scores on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (19) , our primary outcome measure, or on secondary outcomes, which were the Sheehan Disability Scale (20) , HAM-D, (21) , and HAM-A (22) ( Table 2 ).

Comparative Efficacy

Table 2 presents comparative outcome results between treatments from intention-to-treat analyses. Panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy showed significantly superior reduction in severity of a broad range of panic symptoms measured by the Panic Disorder Severity Scale ( Table 2 ). The substantial treatment effect was reflected in the between-group effect size (Cohen’s d) of 0.95. Using the a priori definition of response (9) as a 40% decrease in the total Panic Disorder Severity Scale score from baseline, panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy had a significantly higher response rate than applied relaxation training (73% versus 39%; p=0.08). Panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy also yielded significantly greater reduction in functional impairment (Sheehan Disability Scale, Cohen’s d=0.74) and a tendency toward greater reduction in HAM-D depressive symptoms (p=0.07). There was no treatment effect on the HAM-A (Cohen’s d=0.16, p=0.58).

Hypothesized Confounds

Randomization failed to balance gender. However, despite differences between the two treatment groups in gender composition, linear regression analysis found neither an association between gender and change in Panic Disorder Severity Scale severity (F=0.37, df=1, 46, p=0.89), nor a treatment by gender interaction (F=0.30, df=1, 45, p=0.58).

The treatment effects were examined in separate, multiple linear regression analyses controlling for each of the following hypothesized confounds: depression diagnosis at baseline, use of psychotropic medication (at baseline), baseline assessment of each outcome variable, and dropout status. These were conducted for the primary outcome and each secondary outcome, and the corresponding baseline assessment of the respective outcome was also included as a covariate in each model. There were no significant main effects for any of the confounds, nor covariate by treatment interactions for any primary or secondary outcomes. It is worth emphasizing that there was no impact on outcome of standard antipanic medication that was stable at baseline and continued throughout the trial.

Attrition

Rates of dropout from the 12-week randomized controlled clinical trial differed significantly between the randomly assigned treatment groups: two out of 26 (7%) panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy subjects and eight out of 23 (34%) applied relaxation training subjects dropped out (χ 2 =5.51, df=1, p=0.03). We made every effort (telephone calls, telegrams, mail, monetary incentives) to continue assessing dropouts, yet only three out of 10 subjects agreed to participate in follow-up ratings after withdrawing from the randomized treatment. The analyses described above adhered to the intention-to-treat principle using last observation forward to impute missing data for the primary outcome and three continuous secondary outcomes. In addition, based on the study protocol criteria, dropouts were classified as nonresponders on the secondary categorical outcome, responder status.

We acknowledge that last observation forward is not an optimal imputation method (32) . However, at the time of protocol development, there was concern that interim assessments during the 12-week randomized controlled clinical trial could potentially have a negative impact on the intensity of the transference. Therefore, to evaluate the sensitivity of the results to the last observation forward strategy, we conducted further analyses limited to those subjects who had a termination rating (i.e., no imputation was used). The results of these sensitivity analyses further support the conclusion that panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy is efficacious, although the magnitude of the effect is attenuated for the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (t=2.24, df=40, p=0.02) and psychosocial functioning (Sheehan Disability Scale: t=2.15, df=38, p=0.01). As with the last observation forward analyses, the other two secondary outcomes did not differ significantly between groups (HAM-D: t=1.11, df=40, p=0.24; HAM-A: t=0.33, df=40, p=0.78).

Adverse Events

One applied relaxation training subject was deemed by her study therapist (the applied relaxation training supervisor [M.S.]) and the objective ombudsman to require antipanic medication because of severe, unrelieved, although not worsening, panic. As outlined in the protocol, she was discharged from the study after session 12 (week 6) and referred for pharmacotherapy.

Discussion

This study constitutes the first efficacy evaluation of an operationalized, testable form of psychodynamic psychotherapy for primary DSM-IV panic disorder in a randomized controlled clinical trial format. Panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy showed efficacy for treatment of core symptoms of panic disorder—panic attacks, limited symptom attacks, and physical anxiety states—and phobic avoidance as measured on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale. Further, it alleviated attendant impairments in psychosocial functioning associated with poor quality of life in panic disorder (33) . Treatment was well tolerated; only two out of 26 subjects failed to complete the 12-week course of treatment.

Great care was taken in the study design to balance therapist experience, training, and supervision in the two groups. The high level of training and experience in both therapist groups may account for higher response rates than might have been predicted in both groups, despite the sickness of this panic disorder population, which included higher rates of moderate to severe agoraphobia and comorbid major depression than many previously studied panic disorder patient cohorts (8 – 11 , 34 , 35) . Many influential panic disorder studies have excluded patients with these comorbidities. None of the applied relaxation training therapists or panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy therapists regularly used the specific, manualized, time-limited study treatment tested as their primary clinical treatment modality outside of the study. Nonetheless, panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy may have represented a treatment that more closely resembled the routine clinical practice of panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy therapists than did applied relaxation training for some applied relaxation training therapists. This might have imparted a bias in favor of panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy.

A further potential source of bias for panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy may be seen in Table 1 . Despite random assignment, applied relaxation training subjects had an insignificantly greater number of axis I and II comorbidities at baseline than panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy subjects. These differences were not reflected in baseline symptom ratings on any outcome measures ( Table 2 ).

This small study was adequately powered to discern large between-group effect sizes on the primary outcome measure of panic disorder and in psychosocial functioning. The small cohort size (N=49) had limited power to detect small to moderate group differences in other domains, such as depression. This is not surprising; only 23% of subjects met criteria for comorbid major depression. With eight panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy therapists and six applied relaxation training therapists, the therapist-specific cohort sizes were too small to test for therapist effects.

This study has several limitations. The two cells had differential dropout. The low dropout rate in panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy may attest to its tolerability for panic disorder subjects (7%), since dropout rates have been significantly higher for all other forms of tested treatments in clinical trials of panic disorder. In comparison, the Multicenter Panic Disorder Study (9) dropout rates were 27% for CBT alone, 39% for imipramine alone, 28% for CBT plus imipramine, and 29% for placebo.

The low panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy attrition rate may reflect the relatively flexible approach of psychodynamic psychotherapy, which can be accommodated to a more generalizable cohort of panic disorder patients with a wide variety of comorbidities within the constraints of a manualized treatment, since it is based on an approach not limited to specific psychiatric symptoms. The low panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy dropout rate corroborates findings from our open trial (23 , 24) , in which attrition was 19%. The higher dropout rate in the open trial may reflect that study design, which tapered patients from all antipanic medication prior to study entry, including benzodiazepines, rather than permitting continuation of stable medication.

In this trial, the outcome of psychodynamic psychotherapy compared well with previous trials of efficacious treatments for panic disorder (8 – 10 , 35 , 36) . Yet this study made no direct comparisons to CBT and medication; hence determination of relative efficacy of panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy must await future studies.

Psychodynamic psychotherapy and CBT provide different approaches to psychotherapy. CBT is highly structured, assigns homework, and includes exposure to patients’ fears and physical anxieties. Psychodynamic psychotherapy is far less structured, has no homework, and never emphasizes exposure, attending instead to articulation of the relationship with the therapist and to understanding the psychological significance of panic and phobic avoidance. The profound differences between these therapies may mean that they appeal to and treat different groups of panic disorder patients. Alternatively, differences in technique might mask underlying “common factor” effects that might yield equivalent outcomes. Such a comparison now appears worth testing. The differences between therapies could also reflect epiphenomena of the panic syndrome through which response can be achieved.

1. Katon W: Panic disorder: relationship to high medical utilization, unexplained physical symptoms, and medical costs. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 10):11–18Google Scholar

2. Swinson RP, Cox BJ, Woszczyna CB: Use of medical services and treatment for panic disorder with agoraphobia and for social phobia. CMAJ 1992; 147:878–883Google Scholar

3. Markowitz JS, Weissman MM, Ouellette R, Lish LD, Kleman GL: Quality of life in panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:984–992Google Scholar

4. Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Ouellete R, Johnson J, Greenwald S: Panic attacks in the community: social morbidity and health care utilization. JAMA 1991; 265:742–746Google Scholar

5. Shear MK, Maser JD: Standardized assessment for panic disorder research: a conference report. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:346–354Google Scholar

6. Lydiard B, Otto M, Milrod B: Panic Disorder, in Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders, 3rd ed. Edited by Gabbard G. Arlington, Va, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2001, pp 1447–1485Google Scholar

7. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Panic Disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155 (May suppl)Google Scholar

8. Craske MG, Brown TA, Barlow DH: Behavioral treatment of panic disorder: a two-year follow-up. Behav Ther 1991; 22:289–304Google Scholar

9. Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, Woods SW: Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder. JAMA 2000; 283:2529–2536Google Scholar

10. Marks IM, Swinson RP, Basoglu M, Kuch K, Noshirvani H, O’Sullivan G, Lelliott PT, Kirby M, McNamee G, Sengun S, Wickwire K: Alprazolam and exposure alone and combined in panic disorder with agoraphobia: a controlled study in London and Toronto. Br J Psych 1993; 162:776–787Google Scholar

11. Wiborg IM, Dahl AA: Does brief dynamic psychotherapy reduce the relapse rate of panic disorder? Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:689–694Google Scholar

12. Chambless DL, Peterman M: A Meta-Analysis of Cognitive Therapy of Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Panic Disorder: The Second Decade, in New Advances in Cognitive Therapy. Edited by Leahy RL. New York, Guilford (in press)Google Scholar

13. Hofmann SG, Barlow DH, Papp LA, Detweiler MF, Ray SE, Shear MK, Woods SW, Gorman JM: Pretreatment attrition in a comparative treatment outcome study on panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:43–47Google Scholar

14. Milrod B, Shear MK: Dynamic treatment of panic disorder: a review. J Ment Dis 1991; 179:741–743Google Scholar

15. Milrod B, Busch F, Cooper A, Shapiro T: Manual of Panic-Focused Psychodynamic Psychotherapy. Arlington, Va, American Psychiatric Publishing, 1997Google Scholar

16. Öst LG, Westling BE: Applied relaxation versus cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of panic disorder. Behav Res Ther 1995; 33:145–158Google Scholar

17. Gorman J, Shear MK, McIntyre JS, Zarin DA: American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Panic Disorder (reply letter). Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1799Google Scholar

18. Brown TA, DiNardo P, Barlow DH: Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime Version (ADIS-IV-L). New York, Graywinds Publications, 1995Google Scholar

19. Shear MK, Brown TA, Barlow DH, Money R, Sholomskas DE, Woods SW, Gorman JM, Papp LA: Multicenter collaborative Panic Disorder Severity Scale. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1571–1575Google Scholar

20. Sheehan DV: The Sheehan Disability Scales, in The Anxiety Disease. New York, Charles Scribner and Sons, 1983, p 151Google Scholar

21. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Google Scholar

22. Hamilton M: The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1959; 32:50–55Google Scholar

23. Milrod B, Busch F, Leon AC, Aronson A, Roiphe J, Rudden M, Singer M, Shapiro T, Goldman H, Richter D, Shear MK: A pilot open trial of brief psychodynamic psychotherapy for panic disorder. J Psychother Pract Res 2001; 10:239–245Google Scholar

24. Milrod B, Busch F, Leon AC, Shapiro T, Aronson A, Roiphe J, Rudden M, Singer M, Goldman H, Richter D, Shear MK: Open trial of psychodynamic psychotherapy for panic disorder: a pilot study. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1878–1880Google Scholar

25. Beck JG, Stanley MA, Baldwin LE, Deagle EA, Averill PM: Comparison of cognitive therapy and relaxation training for panic disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994; 62:818–826Google Scholar

26. Leber P: The placebo control in clinical trials (a view from the FDA). Psychopharm Bull 1986; 22:30–32Google Scholar

27. Leber PD: The hazards of inference: the active control investigation. Epilepsia 1986; 30(suppl 1):S57–S63Google Scholar

28. Leon AC: Are two antidepressant mechanisms better than one? issues in clinical trial design and analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:31–36Google Scholar

29. US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration: Guidance for Industry; E10 Choice of control group and related issues in clinical trials. Washington, DC, May 2001Google Scholar

30. Leon AC, Portera L, Lowell K, Rheinheimer D: A strategy to evaluate a covariate by group interaction in an analysis of covariance. Psychopharmacol Bull 1999; 34:805–809Google Scholar

31. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW, Benjamin L: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II), version 2.0. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department, 1994Google Scholar

32. Leon AC, Mallinckrodt CH, Chuang-Stein C, Archibald DG, Archer GE, Chartier K: Attrition in randomized controlled clinical trials: methodological issues in psychopharmacology. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 59:1001–1005Google Scholar

33. Leon AC, Portera L, Weissman MM: The social costs of anxiety disorders. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166(suppl 27):19–22Google Scholar

34. Mavissakalian M, Michelson L: Two-year follow-up of exposure and imipramine treatment of agoraphobia. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:1106–1112Google Scholar

35. Clark DM, Salkovskis PM, Hackman A, Middleton H, Anastasiades P, Gelder M: A comparison of cognitive therapy, applied relaxation, and imipramine in the treatment of panic disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 164:759–769Google Scholar

36. Fava GA, Zielezny M, Savron G, Grandi S: Long-term effects of behavioral treatment for panic disorder with agoraphobia. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:87–92Google Scholar