A Comparison of Lithium and T 3 Augmentation Following Two Failed Medication Treatments for Depression: A STAR*D Report

Abstract

Objective: More than 40% of patients with major depressive disorder do not achieve remission even after two optimally delivered trials of antidepressant medications. This study compared the effectiveness of lithium versus triiodothyronine (T 3 ) augmentation as a third-step treatment for patients with major depressive disorder. Method: A total of 142 adult outpatients with nonpsychotic major depressive disorder who had not achieved remission or who were intolerant to an initial prospective treatment with citalopram and a second switch or augmentation trial were randomly assigned to augmentation with lithium (up to 900 mg/day; N=69) or with T 3 (up to 50 μg/day; N=73) for up to 14 weeks. The primary outcome measure was whether participants achieved remission, which was defined as a score ≤7 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Results: After a mean of 9.6 weeks (SD=5.2) of treatment, remission rates were 15.9% with lithium augmentation and 24.7% with T 3 augmentation, although the difference between treatments was not statistically significant. Lithium was more frequently associated with side effects (p=0.045), and more participants in the lithium group left treatment because of side effects (23.2% versus 9.6%; p=0.027). Conclusions: Remission rates with lithium and T 3 augmentation for participants who experienced unsatisfactory results with two prior medication treatments were modest and did not differ significantly. The lower side effect burden and ease of use of T 3 augmentation suggest that it has slight advantages over lithium augmentation for depressed patients who have experienced several failed medication trials.

While antidepressant medications are effective for major depressive disorder, only 25%–45% of patients experience remission after one acute trial of an antidepressant (1 – 3) . For patients whose depression does not remit after an adequate trial, clinicians generally switch to a different antidepressant, add a second antidepressant to the initial one, or augment the antidepressant with another agent. The most widely studied medications used for augmentation of antidepressant treatment are lithium and triiodothyronine (T 3 ), but most of the evidence supporting their use in augmentation was collected in studies with patients who did not respond initially to tricyclic antidepressants (4) . We know of no studies that have compared the effectiveness of these two augmentation treatments as third-step options for depressed patients who did not receive sufficient benefit from treatment trials with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or other second-generation antidepressants.

Augmentation With Lithium or T 3

The rationale for using lithium as an augmenting agent in antidepressant treatment for patients with major depression was based on preclinical data showing that lithium increases the presynaptic formation, storage, and release of serotonin (5) . It was postulated that the increase in serotonergic function induced by lithium would have a synergistic effect on the mechanism of action of antidepressants. Most studies of lithium augmentation used small samples of patients who had not responded to tricyclic antidepressants, and most found that augmenting a tricyclic with lithium was effective. A meta-analysis of nine placebo-controlled studies (total N=234) supported the conclusion that lithium augmentation was effective, with a number needed to treat of 3.8 (6) . Patients who responded and who continued taking lithium in addition to their antidepressant stayed well longer than those who were randomly switched to placebo augmentation (7) . However, there is no good evidence that lithium is effective in augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (8) .

The hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis and its reciprocal relationship with depression have long been a subject of inquiry (9 , 10) . Although pretreatment thyroid function may or may not mediate response to antidepressants (11 , 12) , thyroid hormone augmentation is useful even in the absence of thyroid abnormalities (13) . Putative mechanisms of action include desensitization of 5-HT 1A inhibitory receptors, direct effects on nuclear receptors affecting gene expression (14) , and increased brain metabolism (15) . A meta-analysis of eight studies (total N=292) supported the efficacy of T 3 augmentation, with a number needed to treat of 4.3 (16) . In contrast to lithium augmentation, to our knowledge no studies have examined the durability of response to T 3 augmentation with a placebo-substitution design. A meta-analysis (17) showed that T 3 augmentation may speed up response to antidepressants, especially in women, but neither an acceleration effect nor a gender effect was replicated in a small controlled study with paroxetine (18) .

Effectiveness and Comparison Studies

Few studies have assessed the effectiveness (that is, in representative patients treated in typical practice settings) of using other agents to augment antidepressants, particularly to augment the more modern antidepressants. Even fewer studies have prospectively generated a cohort of patients who obtained insufficient benefit from adequately delivered initial treatments and then underwent randomized assignment to receive augmentation with lithium or other agents (8 , 19 , 20) . Similarly, few studies have examined the efficacy or effectiveness of T 3 augmentation for patients with major depression who did not have an adequate response to one of the second-generation antidepressants (15) . Joffe et al. (21) , in the only study we know of that directly compared lithium and T 3 augmentation of tricyclic antidepressants as a second-step treatment, found the two agents to be equally effective and more effective than placebo.

In this study, we compared the effectiveness, tolerability, and safety of lithium and T 3 augmentation in a representative group of primary and specialty care clinic outpatients who had nonpsychotic major depressive disorder. The study participants had not obtained adequate benefit from prospective treatment with two or more trials of antidepressant monotherapy or an initial trial of monotherapy with citalopram followed by a second trial in which citalopram was augmented with buspirone or sustained-release bupropion. In addition, a small number of patients who entered this trial (N=9) initially received citalopram, then received cognitive therapy either alone or combined with citalopram, and then underwent randomized assignment to either sustained-release bupropion or extended-release venlafaxine alone before moving on to the augmentation treatment we report here.

Method

This trial was conducted as part of the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study, which was designed to assess the effectiveness of medications or cognitive therapy for outpatients who had not had a satisfactory response to an initial treatment or to one or more subsequent prospective treatments (3 , 22–24) . The rationale, design, and methods of STAR*D have been detailed elsewhere (25 , 26) .

Participants

The institutional review boards at the STAR*D National Coordinating Center, the Data Coordinating Center, each regional center and relevant clinical site, and the Data Safety and Monitoring Board of the National Institute of Mental Health (Bethesda, Md.) approved and monitored the protocol. All participants received a complete description of the study and provided written informed consent at the time of enrollment into the initial treatment step and into each subsequent treatment step, including the augmentation treatment described here.

Between July 2001 and April 2004, a total of 4,041 outpatients 18 to 75 years of age were enrolled in STAR*D from primary care (N=18) and psychiatric practice settings (N=23) that serve patients with public as well as private insurance. To be eligible for enrollment, patients had to have a primary clinical diagnosis of nonpsychotic major depressive disorder according to DSM-IV criteria, confirmed by a checklist completed by clinical research coordinators at each site. Advertising for participants was proscribed. The study used minimal exclusion criteria, aiming for broad inclusion in order to maximize the generalizability of findings (25 , 26) . Of the 4,041 participants enrolled in STAR*D, 142 enrolled in the augmentation treatment step, which was the third treatment level in the study.

Progression to STAR*D Level 3

STAR*D consisted of four levels of medication treatment, and for some participants it included an additional treatment trial with cognitive therapy either alone or combined with citalopram (Level 2A). At each level, participants who achieved remission (defined as a score ≤5 on the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology—Clinician Rating [QIDS-C] [ 27 – 29 ]) and had no trouble tolerating the medication could proceed to the 12-month naturalistic follow-up stage of the project. Those who had a partial response to the medication (defined as a reduction ≥50% from the baseline QIDS-C score) but did not remit at any treatment level could enter the follow-up stage but were encouraged to enroll in the next treatment level; the same protocol applied to those who neither achieved remission nor had a response to treatment and those who were intolerant of the treatment.

All STAR*D participants entered treatment Level 1 and underwent a trial of citalopram. Participants who entered Level 2 were randomly assigned either to switch to one of four alternative treatments (sustained-release bupropion, sertraline, extended-release venlafaxine, or cognitive therapy) or to receive augmentation of the citalopram with one of three treatments (sustained-release bupropion, buspirone, or cognitive therapy) (30) . Those who had an unsatisfactory response (intolerance or lack of remission) could enter treatment Level 3. Participants who had an unsatisfactory response to cognitive therapy during Level 2, whether they were enrolled in cognitive therapy as a medication switch or as augmentation, could enter Level 2A, which compared the effectiveness of two of the switch options (sustained-release bupropion and extended-release venlafaxine). The inclusion of treatment Level 2A in the study ensured that all participants entering Level 3 had not had a satisfactory response to two different medication treatments.

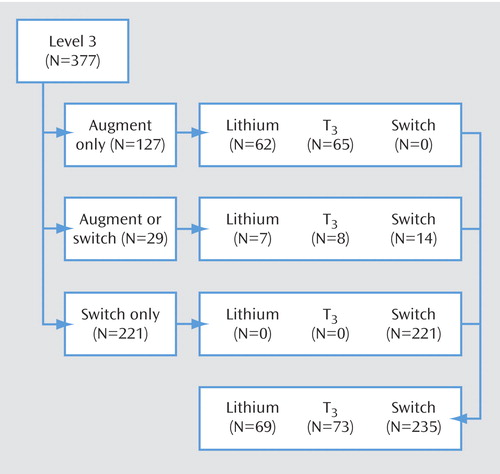

On entry to treatment Level 3, participants were asked whether they were willing to accept random assignment to a medication switch to either nortriptyline or mirtazapine and whether they were willing to accept random assignment to augmentation of their current antidepressant with lithium or T 3 . Those who would accept only a medication switch strategy were randomly assigned to switch to nortriptyline or mirtazapine; those who would accept only an augmentation strategy were randomly assigned to augmentation with either lithium or T 3 ; and those who would accept either a switch or an augmentation strategy were randomly assigned to one of the four treatment options.

In this report we compare the main outcomes for Level 3 participants who agreed to random assignment to treatment strategies that included any of the augmentation treatments. Participants were randomly assigned to these treatments in a 1:1 ratio stratified for treatment acceptability and regional center. Of the 18 patients who exited Level 2A, nine were willing to accept a medication switch only, and nine were willing to accept augmentation only. Of the nine who accepted augmentation only, six received lithium and three received T 3 .

Protocol Treatment

To mimic clinical practice, enhance safety, and ensure vigorous dosing, treatment assignment and dose were not masked to participants or treating clinicians. A clinical procedures manual (31) recommended starting doses and dose changes for each medication treatment in order to deliver measurement-based care (22 , 32) . The dosing protocol was flexible, however, and could be adjusted according to the clinician’s assessment of symptoms and side effects as measured at each visit with the QIDS-C and with ratings of the frequency, intensity, and burden of side effects (26 , 33 , 34) . In addition, didactic instruction, clinical research coordinator support, and a centralized monitoring system (35) with feedback were used to ensure that timely dose increases were made as long as symptom reduction was inadequate and side effects remained acceptable. Clinical management aimed to achieve symptom remission (a QIDS-C score ≤5 at treatment exit). The protocol recommended treatment clinic visits at weeks 0, 2, 4, 6, 9, and 12 but allowed for flexibility (e.g., the week 2 visit could take place within 6 days before or after that date), and extra visits could be made if needed. For participants who achieved remission, treatment was maintained for an additional 2 weeks to determine whether the remission would be sustained. For participants who had a response but had not remitted by week 12, treatment could be extended for an additional 2 weeks.

The two augmentation options used at treatment Level 2, buspirone and sustained-release bupropion, were discontinued without tapering at the initial Level 3 treatment visit. Lithium or T 3 was added to ongoing treatment with citalopram, sertraline, sustained-release bupropion, or extended-release venlafaxine. Lithium was started at 450 mg/day, and at week 2 it was increased to the recommended dose of 900 mg/day. If participants could not tolerate the initial dose, it could be reduced to 225 mg/day for 1 week then increased to 450 mg/day. T 3 was started at 25 μg/day for 1 week and then increased to the recommended dose of 50 μg/day. As noted, this protocol was flexible, allowing a role for clinical judgment and ratings of symptoms and side effects.

Concomitant Treatments

Stimulants, anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, antidepressants that were not included in the study’s protocol, and potential antidepressant augmenting agents (e.g., buspirone) were proscribed. Otherwise, any concomitant medication was allowed for management of concurrent general medical conditions as well as side effects of antidepressants used in the study (e.g., sexual dysfunction). Anxiolytics (except alprazolam) and sedative-hypnotics were permitted (including up to 200 mg of trazodone at bedtime for sleep).

Measures

Clinical and demographic characteristics were recorded at baseline for treatment Level 1 (22) . The Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (36 , 37) was used to assess for general medical conditions and the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (38 – 40) to assess for comorbid psychiatric disorders. At entry and exit from treatment Level 3, overall functioning and satisfaction were assessed with the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (41) , the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (42) , the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (43) , and the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (44) , all administered through an automated interactive voice response telephone system (45 , 46) .

The primary outcome measure was whether participants achieved symptom remission, defined as a score ≤7 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) (47) . The HAM-D was administered via telephone in the course of structured interviews (conducted in English or Spanish) within 5 days of entry and exit from treatment Level 3 by independent research outcomes assessors who were blind to participants’ treatments. The assessors also administered the 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology—Clinician-Rated (27 , 29 , 48) to assess depressive symptom severity and associated symptom features. The secondary outcome measures were whether participants experienced remission and response as assessed by the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology—Self-Report (QIDS-SR) (27 – 29 , 33) , with remission defined as a total QIDS-SR score ≤5 at exit from treatment Level 3 and response defined as a reduction of ≥50% from the Level 3 baseline QIDS-SR score. The QIDS-SR was administered at each treatment visit, along with ratings of the frequency, intensity, and burden of side effects.

Statistical Methods

For summary statistics, means and standard deviations were computed for continuous variables, and counts and percentages for discrete variables. Student’s t tests and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare continuous baseline clinical and demographic characteristics, treatment features, and ratings of side effects and serious adverse events across treatments. Chi-square tests were used to compare discrete characteristics across treatments.

Logistic regression models were used to compare remission and response rates after adjusting for treatment acceptability category (“augmentation only” or “switch or augmentation”), baseline severity of depression as assessed by the QIDS-SR, and age at onset of first major depressive episode. The time to first remission was defined as the first clinic visit with a QIDS-SR score £5, and time to first response was defined as the first clinic visit with a reduction ³50% from the baseline QIDS-SR score. Log-rank tests were used to compare the cumulative proportion of participants who experienced remission or response across the two treatment groups.

Participants whose exit HAM-D scores were missing were assumed not to have achieved remission. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine whether this method of addressing the missing data had an impact on the results of the study. An additional method of addressing these missing data used an imputed value generated from an item response theory analysis of the relationship between the HAM-D and the QIDS-SR.

Results

Patient Disposition

Figure 1 summarizes the Level 3 treatment groups by treatment acceptability category. The 127 Level 3 participants who agreed only to augmentation strategies were randomly assigned to receive either lithium or T 3 . Of the 29 participants who agreed to either an augmentation or a switch strategy, 15 were randomly assigned to receive lithium or T 3 . Thus, a total of 142 participants began Level 3 augmentation treatment.

Overall and Group Baseline Characteristics

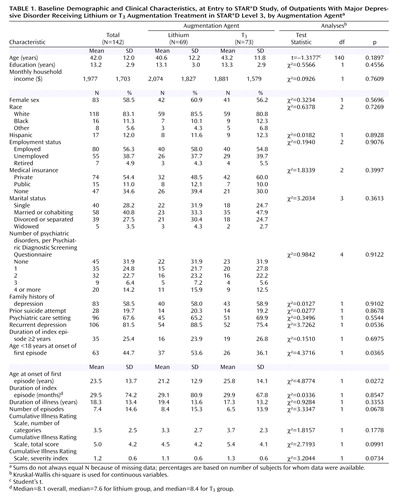

Table 1 summarizes demographic characteristics and relevant elements of participants’ pretreatment clinical history, along with results of the statistical tests used to compare the two augmentation treatment groups. No statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups except that a greater proportion of participants in the lithium group had their first major depressive episode before the age of 18 years, and the mean age at onset of the first episode was lower in the lithium group.

Baseline Symptom Severity, Functioning, and Depressive Features

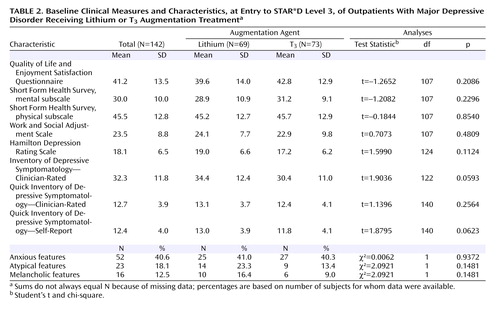

Table 2 summarizes the participants’ clinical characteristics and baseline scores on various assessment instruments at the time of randomization for STAR*D treatment Level 3. Assessment scores indicate a moderate degree of symptom severity overall. Baseline scores on the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire, the physical and mental subscales of the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey, and the Work and Social Adjustment Scale revealed very poor life satisfaction and function. There were no statistically significant differences between groups on measures for depressive symptoms, functioning, or depressive features.

Prior Treatment

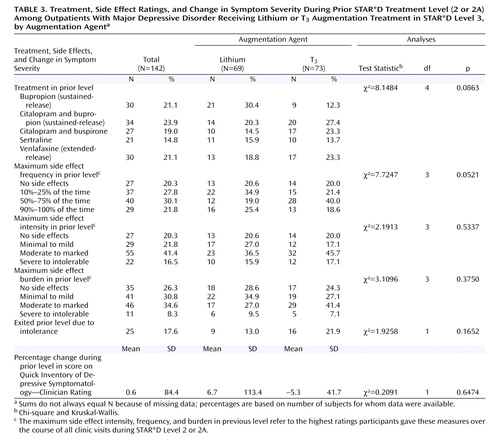

As shown in Table 3 , in the prior treatment step (Level 2 or 2A), participants had been undergoing treatment with sustained-release bupropion, sertraline, extended-release venlafaxine, citalopram plus sustained-release bupropion, or citalopram plus buspirone, in proportions ranging from about 15% to 24%. Some 43% had been receiving citalopram and thus continued to receive citalopram in Level 3, augmented with either lithium or T 3 . Overall mean daily doses at exit from treatment Levels 2 or 2A were as follows: sustained-release bupropion, 395.0 mg (SD=48.0); sertraline, 183.3 mg (SD=24.2); extended-release venlafaxine, 316.3 mg (SD=73.5); sustained-release bupropion (combined with citalopram), 326.5 mg (SD=87.2); and buspirone (combined with citalopram), 46.7 mg (SD=15.2). The mean durations of Level 2 treatments were as follows: sustained-release bupropion, 12.7 weeks (SD=2.4); sertraline, 12.1 weeks (SD=3.0); extended-release venlafaxine, 12.9 weeks (SD=2.4); sustained-release bupropion combined with citalopram, 11.3 weeks (SD=3.8); and buspirone combined with citalopram, 10.4 weeks (SD=4.1). Because participants who were taking citalopram in Level 2 had already been taking it as monotherapy in Level 1, the mean time on citalopram was 22.0 weeks (SD=4.5), almost twice as long as for the other antidepressants administered in Level 2. No statistically significant differences in the durations of these treatments were observed between the lithium and T 3 groups.

The median change in QIDS-C scores for these participants during Level 2 or 2A treatment was 10.8% (range, 70%–900%; one patient entered Level 2 with a QIDS-C score of 1 and left with a score of 10). During these treatment levels, 51.9% of participants had side effects more than half of the time, 57.9% had at least moderate side effect intensity, and 42.9% had at least a moderate side effect burden. No statistically significant differences were observed between the lithium and T 3 groups in any of these variables. Although the mean baseline QIDS-SR score at entry into Level 3 was higher in the lithium group, the difference was clinically, although not statistically, significant, so baseline QIDS-SR score was used as an adjustment factor for the analyses of outcomes.

Duration and Dose of Lithium and T 3 Augmentation

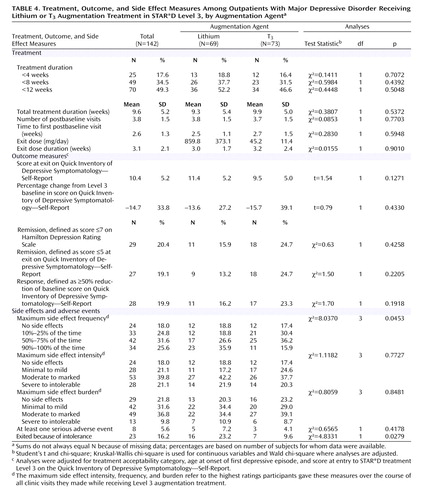

The overall mean duration of augmentation treatment during Level 3 was 9.6 weeks (SD=5.2); 17.6% of the participants received augmentation treatment for less than 4 weeks and 34.5% for less than 8 weeks ( Table 4 ). The mean time on the exit dose was 3.1 weeks (SD=2.1). The duration of treatment was not significantly different between the two groups. Mean daily doses at exit were 859.8 mg (SD=373.1) for lithium and 45.2 μg (SD=11.4) for T 3 . The median lithium blood level, which was assessed in 39 (56.5%) of the 69 participants who received lithium augmentation, was 0.6 meq/liter.

Outcomes for Lithium and T 3 Augmentation

On the primary outcome measure, 15.9% of participants in the lithium group and 24.7% of those in the T 3 group achieved remission; the difference between groups was not significant after adjustment for treatment acceptability category, age at onset of first major depressive episode, and QIDS-SR score at entry into Level 3. There were no statistically significant differences in mean QIDS-SR scores at exit or in overall remission rates as assessed by the QIDS-SR (score ≤5 at exit from Level 3), the percentage reduction from the baseline QIDS-SR score, or the proportion of participants who responded to augmentation treatment (reduction of ≥50% from baseline QIDS-SR). No significant differences were observed in the proportion of participants who reached remission with lithium or T 3 augmentation for those who were taking citalopram, sertraline, sustained-release bupropion, or extended-release venlafaxine (data not shown).

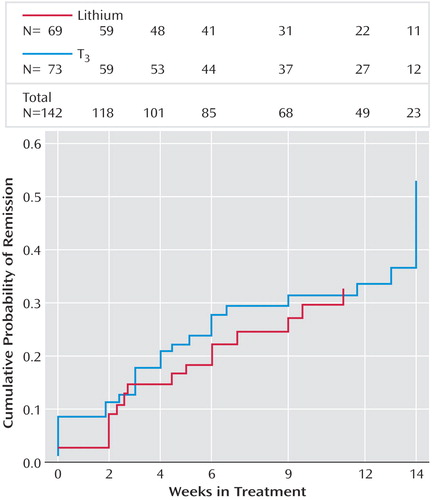

Among participants who responded, the mean time to response was 5.7 weeks (SD=5.1) for participants receiving lithium augmentation and 6.0 weeks (SD=5.1) for those receiving T 3 augmentation. Among those who remitted, the mean time to remission was 7.4 weeks (SD=4.4) for those receiving lithium and 6.6 weeks (SD=4.8) for those receiving T 3 . Kaplan-Meier survival estimates showed that time to response (log rank=0.065, p=0.80) and time to remission (log rank=1.0205, p=0.3124) were not significantly different between the two groups ( Figure 2 ).

a Remission was defined as the first score score £5 on the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology—Self-Report.

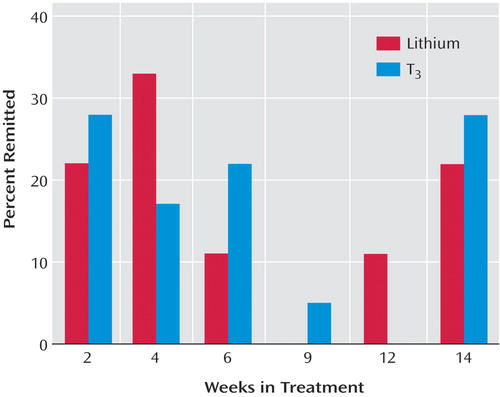

Figure 3 shows the proportions of participants, among all those who eventually achieved remission, who remitted after 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, and 14 weeks of treatment. At week 2, about one-quarter of those who eventually remitted from each treatment group reached remission, and at week 4, another 33% from the lithium group and another 17% from the T 3 group reached remission. The cumulative proportions of participants, among all those who eventually remitted, who had remitted by weeks 4 and 6 were 55% and 66% for the lithium group and 45% and 67% for the T 3 group; 22% in the lithium group and 28% in the T 3 group did not reach remission until week 14. None of the baseline variables listed in Table 2 differentiated those who remitted in the two groups.

a Remission was defined as the first score score £5 on the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology—Self-Report.

Side Effects and Tolerability

Few participants experienced serious adverse events, and no serious psychiatric adverse events occurred. More of those in the lithium group reported the maximum frequency, intensity, and burden of side effects, although the difference between groups was significant only for frequency. Significantly more of those taking lithium exited treatment because of side effects. In general, the odds of experiencing side effects were higher in the lithium group relative to the T 3 group, independent of the effect of treatment acceptability category, age at onset of first major depressive episode, severity of depressive symptoms at baseline for Level 3, and side effect measures (frequency, intensity, and burden) in the prior level. However, these results were significant only with respect to frequency of side effects (odds ratio=2.0, p=0.0465), and not the intensity (odds ratio=1.4, p=0.3512) and burden (odds ratio=1.3, p=0.4531) of side effects.

Discussion

Effectiveness and Tolerability

This is the first randomized, controlled effectiveness study to compare lithium and T 3 augmentation for outpatients with nonpsychotic major depressive disorder who had not obtained adequate benefit from two prior medication treatment attempts. Only a modest proportion of participants achieved remission. The two treatment groups did not differ significantly in the proportion who responded or remitted, in time to response or remission, or in exit measures of depressive symptom severity. While no significant differences were observed in the symptom-based outcome measures between the two groups, the group receiving T 3 augmentation consistently had greater proportions of responders and remitters, greater decreases in HAM-D and QIDS-SR scores, and greater toleration of treatment.

The modest remission rates observed with lithium augmentation may have been due to the low doses used as a result of limited toleration of side effects. Nevertheless, these results probably reflect what clinicians can expect with lithium augmentation in actual practice. The doses of T 3 used in this study approximate those used in placebo-controlled trials, and given the drug’s tolerability, they were easily reached. For both lithium and T 3 augmentation, the duration of treatment was not only sufficient, but it was substantially greater those of previously reported augmentation trials of these agents, none of which exceeded 6 weeks (6 , 20 , 21) . In this study, the mean duration of augmentation treatment was more than 9 weeks, and hence participants very likely had an adequate exposure to the augmentation agents. The modest remission rates may reflect problems with tolerability of lithium augmentation and the difficult-to-treat nature of many cases of major depression in real-world settings.

The remission rates observed in this study are consistent with those reported in other recent augmentation trials, including lithium augmentation of nortriptyline (21) and fluoxetine (8) and T 3 augmentation of fluoxetine (12) . Compared with results reported by Joffe et al. (21) in the only prior study comparing augmentation with lithium and T 3 after unsatisfactory antidepressant monotherapy, our results show a substantially lower proportion of participants who experienced a response to treatment. Yet in the Joffe et al. study, both the duration of treatment with antidepressants before augmentation and the duration of augmentation treatment were substantially shorter than in our study. Joffe et al. studied 50 participants who received 2 weeks of augmentation with lithium (N=17), T 3 (N=17), or placebo (N=16) after 5 weeks of prospective treatment with either imipramine or desipramine. Although remission rates were not reported, response rates were around 60% for both active augmentation agents and 19% for placebo. One possible explanation for the greater percentage of responders in the Joffe et al. study is that the augmentation may have sped up response to a brief course of antidepressant therapy. It may be, too, that augmentation strategies are more efficacious in treatment with tricyclic antidepressants (8) . A third possibility is that participants in our study, who had already undergone two prior medication trials without achieving remission, had more difficult-to-treat forms of depression. Joffe et al. examined the effects of augmentation after a single, relatively brief trial of antidepressant monotherapy. In an earlier STAR*D report (3) , for participants who had gone through one medication trial (treatment Level 1) without achieving remission and then underwent augmentation with bupropion or buspirone (Level 2), remission rates and response rates were both around 30% (3) .

The T 3 group appeared to tolerate the augmentation better than the lithium group. Almost twice as many participants in the lithium group exited augmentation treatment because of side effects. Few in either group had serious adverse events. Given the greater volume of evidence for lithium augmentation and the paucity of randomized trials of T 3 augmentation with the newer generation of antidepressants, the results we observed with T 3 augmentation were better than expected. Overall, if a clinician has a choice between lithium and T 3 augmentation, these results suggest slight advantages with T 3 , especially for patients who have already had two unsuccessful treatments.

Strengths and Limitations

Among the strengths of this study are that it was conducted in representative real-world practices with patients who presented for care—they were not recruited through advertising. Participants had undergone two prospectively administered medication trials that had failed to bring them to remission. This effectiveness design enhances the ecological validity and the generalizability of the study’s results. Medication treatment was open-label, and clinicians used evidence-based guidelines to optimize dose and duration of treatment. The primary outcome measures were collected by assessors who were blind to participants’ treatments.

This study also had several limitations. First, it did not have the statistical power to reliably detect small differences in remission rates between the augmentation therapies. Second, we did not systematically assess laboratory indices, including pretreatment assessment of thyroid function and serial monitoring of lithium levels. Third, we used open-label administration of the augmentation therapies. Fourth, the study design did not include a placebo control group—a particularly noteworthy limitation, given the low remission rates: it is not possible to confirm that either augmentation therapy was more effective than supportive clinical management along with ongoing antidepressant therapy. Finally, participants in the lithium augmentation group took relatively low doses because of intolerable side effects, and as a result they had minimal blood lithium levels. This limitation leaves open the question of whether keeping the doses of lithium small limits its effectiveness for augmentation (6 , 7) . Yet, as noted earlier, patients in this study took the highest tolerable doses, reflecting the reality of prescribing lithium to patients with major depressive disorder who present for care in everyday practice.

Conclusion

Difficult-to-treat depression presents a serious challenge for clinicians and patients. This study highlights the need for strategies beyond following a simple sequence of treatments. In a sample of outpatients with major depressive disorder who had not reached remission despite two prior prospective treatments, we observed modest remission rates with lithium and T 3 augmentation. Our results suggest that in cases where an augmentation trial is deemed appropriate for the patient, T 3 has slight advantages over lithium in effectiveness and tolerability. T 3 also offers the advantages of ease of use and lack of a need for blood level monitoring.

The focus of this study was on the acute outcome of augmentation treatment. Future analyses of STAR*D data will describe longer-term outcomes for patients who entered the 12-month naturalistic follow-up stage of the project while continuing lithium or T 3 augmentation.

1. Depression Guidelines Panel: Depression in Primary Care, vol II: Treatment of Major Depression: Clinical Practice Guideline 5: AHCPR Publication 93-0551. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, April 1993Google Scholar

2. Nierenberg AA, Wright EC: Evolution of remission as the new standard in the treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60(suppl 22):7–11Google Scholar

3. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, Thase ME, Quitkin F, Warden D, Ritz L, Nierenberg AA, Lebowitz BD, Biggs MM, Luther JF, Shores-Wilson K, Rush AJ: Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1243–1252Google Scholar

4. Ros S, Aguera L, de la GJ, Rojo JE, de Pedro JM: Potentiation strategies for treatment-resistant depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2005; 428:14–24, 36Google Scholar

5. de Montigny C, Grunberg F, Mayer A, Deschenes JP: Lithium induces rapid relief of depression in tricyclic antidepressant drug non-responders. Br J Psychiatry 1981; 138:252–256Google Scholar

6. Bschor T, Lewitzka U, Sasse J, Adli M, Koberle U, Bauer M: Lithium augmentation in treatment-resistant depression: clinical evidence, serotonergic and endocrine mechanisms. Pharmacopsychiatry 2003; 36(suppl 3):S230–S234Google Scholar

7. Bauer M, Bschor T, Kunz D, Berghofer A, Strohle A, Muller-Oerlinghausen B: Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the use of lithium to augment antidepressant medication in continuation treatment of unipolar major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1429–1435Google Scholar

8. Fava M, Alpert J, Nierenberg A, Lagomasino I, Sonawalla S, Tedlow J, Worthington J, Baer L, Rosenbaum JF: Double-blind study of high-dose fluoxetine versus lithium or desipramine augmentation of fluoxetine in partial responders and nonresponders to fluoxetine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2002; 22:379–387Google Scholar

9. Flach FF, Celian CI, Rawson RW: Treatment of psychiatric disorders with triiodothyronine. Am J Psychiatry 1958; 114:841–842Google Scholar

10. Prange AJ Jr, Wilson IC, Rabon AM, Lipton MA: Enhancement of imipramine antidepressant activity by thyroid hormone. Am J Psychiatry 1969; 126:457–469Google Scholar

11. Howland RH: Thyroid dysfunction in refractory depression: implications for pathophysiology and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 1993; 54:47–54Google Scholar

12. Iosifescu DV, Howarth S, Alpert JE, Nierenberg AA, Worthington JJ, Fava M: T 3 blood levels and treatment outcome in depression. Int J Psychiatry Med 2001; 31:367–373 Google Scholar

13. Joffe RT, Levitt AJ, Bagby RM, MacDonald C, Singer W: Predictors of response to lithium and triiodothyronine augmentation of antidepressants in tricyclic non-responders. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 163:574–578Google Scholar

14. Newman ME, Agid O, Gur E, Lerer B: Pharmacological mechanisms of T3 augmentation of antidepressant action. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2000; 3:187–191Google Scholar

15. Iosifescu DV, Nierenberg AA, Mischoulon D, Perlis RH, Papakostas GI, Ryan JL, Alpert JE, Fava M: An open study of triiodothyronine augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66:1038–1042Google Scholar

16. Aronson R, Offman HJ, Joffe RT, Naylor CD: Triiodothyronine augmentation in the treatment of refractory depression: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:842–848Google Scholar

17. Altshuler LL, Bauer M, Frye MA, Gitlin MJ, Mintz J, Szuba MP, Leight KL, Whybrow PC: Does thyroid supplementation accelerate tricyclic antidepressant response? a review and meta-analysis of the literature. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1617–1622Google Scholar

18. Appelhof BC, Brouwer JP, van DR, Fliers E, Hoogendijk WJ, Huyser J, Schene AH, Tijssen JG, Wiersinga WM: Triiodothyronine addition to paroxetine in the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004; 89:6271–6276Google Scholar

19. Birkenhäger TK, van den Broek WW, Mulder PG, Bruijn JA, Moleman P: Comparison of two-phase treatment with imipramine or fluvoxamine, both followed by lithium addition, in inpatients with major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:2060–2065Google Scholar

20. Nierenberg AA, Papakostas GI, Petersen T, Montoya HD, Worthington JJ, Tedlow J, Alpert JE, Fava M: Lithium augmentation of nortriptyline for subjects resistant to multiple antidepressants. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003; 23:92–95Google Scholar

21. Joffe RT, Singer W, Levitt AJ, MacDonald C: A placebo-controlled comparison of lithium and triiodothyronine augmentation of tricyclic antidepressants in unipolar refractory depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:387–393Google Scholar

22. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Warden D, Ritz L, Norquist G, Howland RH, Lebowitz B, McGrath PJ, Shores-Wilson K, Biggs MM, Balasubramani GK, Fava M; STAR*D Study Team: Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:28–40Google Scholar

23. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Stewart JW, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Ritz L, Biggs MM, Warden D, Luther JF, Shores-Wilson K, Niederehe G, Fava M; STAR*D Study Team: Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1231–1242Google Scholar

24. Fava M, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Alpert JE, McGrath PJ, Thase ME, Warden D, Biggs M, Luther JF, Niederehe G, Ritz L, Trivedi MH; STAR*D Study Team: A comparison of mirtazapine and nortriptyline following two consecutive failed medication treatments for depressed outpatients: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1161–1172Google Scholar

25. Fava M, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Sackeim HA, Quitkin FM, Wisniewski S, Lavori PW, Rosenbaum JF, Kupfer DJ: Background and rationale for the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003; 26:457–494Google Scholar

26. Rush AJ, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, Lavori PW, Trivedi MH, Sackeim HA, Thase ME, Nierenberg AA, Quitkin FM, Kashner TM, Kupfer DJ, Rosenbaum JF, Alpert J, Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Biggs MM, Shores-Wilson K, Lebowitz BD, Ritz L, Niederehe G; STAR*D Study Team: Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D): rationale and design. Control Clin Trials 2004; 25:119–142Google Scholar

27. Rush AJ, Carmody TJ, Reimitz PE: The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): Clinician (IDS-C) and Self-Report (IDS-SR) ratings of depressive symptoms. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2000; 9:45–59Google Scholar

28. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN, Markowitz JC, Ninan PT, Kornstein S, Manber R, Thase ME, Kocsis JH, Keller MB: The 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), Clinician Rating (QIDS-C), and Self-Report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 54:573–583Google Scholar

29. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Biggs MM, Suppes T, Crismon ML, Shores-Wilson K, Toprac MG, Dennehy EB, Witte B, Kashner TM: The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (IDS-C) and Self-Report (IDS-SR), and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) and Self-Report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: a psychometric evaluation. Psychol Med 2004; 34:73–82Google Scholar

30. Lavori PW, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Alpert J, Fava M, Kupfer DJ, Nierenberg A, Quitkin FM, Sackeim HA, Thase ME, Trivedi M: Strengthening clinical effectiveness trials: equipoise-stratified randomization. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 50:792–801Google Scholar

31. Trivedi MH, Stegman D, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA: STAR*D Clinical Procedures Manual. Unpublished manuscript, July 31, 2002. Available at www.edc.pitt.edu/stard/public/study_manuals.htmlGoogle Scholar

32. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Gaynes BN, Stewart JW, Wisniewski SR, Warden D, Ritz L, Luther J, Stegman D, DeVeaugh-Geiss J, Howland RH: Maximizing the adequacy of medication treatment in controlled trials and clinical practice: STAR*D measurement-based care. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006 (in press)Google Scholar

33. Rush AJ, Bernstein IH, Trivedi MH, Carmody TJ, Wisniewski S, Mundt JC, Shores-Wilson K, Biggs MM, Woo A, Nierenberg AA, Fava M: An evaluation of the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: a Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression trial report. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 59:493–501Google Scholar

34. Wisniewski SR, Rush AJ, Balasubramani GK, Trivedi MH, Nierenberg AA; for the STAR*D Investigators: Self-rated global measure of the frequency, intensity, and burden of side effects. J Psychiatr Pract 2006; 12:71–79Google Scholar

35. Wisniewski SR, Eng H, Meloro L, Gatt R, Ritz L, Stegman D, Trivedi M, Biggs MM, Friedman E, Shores-Wilson K, Warden D, Bartolowits D, Martin JP, Rush AJ: Web-based communications and management of a multi-center clinical trial: the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) project. Clin Trials 2004; 1:387–398Google Scholar

36. Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L: Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 1968; 16:622–626Google Scholar

37. Miller MD, Paradis CF, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Stack JA, Rifai AH, Mulsant B, Reynolds CF III: Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: application of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Psychiatry Res 1992; 41:237–248Google Scholar

38. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI: A self-report scale to help make psychiatric diagnoses: the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:787–794Google Scholar

39. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI: The Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire: development, reliability, and validity. Compr Psychiatry 2001; 42:175–189Google Scholar

40. Rush AJ, Zimmerman M, Wisniewski SR, Fava M, Hollon SD, Warden D, Biggs MM, Shores-Wilson K, Shelton RC, Luther JF, Thomas B, Trivedi MH: Comorbid psychiatric disorders in depressed outpatients: demographic and clinical features. J Affect Disord 2005; 87:43–55Google Scholar

41. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD: A 12-item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996; 34:220–233Google Scholar

42. Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM: The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics 1993; 4:353–365Google Scholar

43. Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK, Greist JH: The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry 2002; 180:461–464Google Scholar

44. Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R: Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull 1993; 29:321–326Google Scholar

45. Mundt JC: Interactive voice response systems in clinical research and treatment. Psychiatr Serv 1997; 48:611–612Google Scholar

46. Kobak KA, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Mundt JC, Katzelnick DJ: Computerized assessment of depression and anxiety over the telephone using interactive voice response. MD Comput 1999; 16:64–68Google Scholar

47. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Google Scholar

48. Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, Jarrett RB, Trivedi MH: The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychol Med 1996; 26:477–486Google Scholar