The Prevalence and Correlates of Adult ADHD in the United States: Results From the National Comorbidity Survey Replication

Abstract

Objective: Despite growing interest in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), little is known about its prevalence or correlates. Method: A screen for adult ADHD was included in a probability subsample (N=3,199) of 18–44-year-old respondents in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, a nationally representative household survey that used a lay-administered diagnostic interview to assess a wide range of DSM-IV disorders. Blinded clinical follow-up interviews of adult ADHD were carried out with 154 respondents, oversampling those with positive screen results. Multiple imputation was used to estimate prevalence and correlates of clinician-assessed adult ADHD. Results: The estimated prevalence of current adult ADHD was 4.4%. Significant correlates included being male, previously married, unemployed, and non-Hispanic white. Adult ADHD was highly comorbid with many other DSM-IV disorders assessed in the survey and was associated with substantial role impairment. The majority of cases were untreated, although many individuals had obtained treatment for other comorbid mental and substance-related disorders. Conclusions: Efforts are needed to increase the detection and treatment of adult ADHD. Research is needed to determine whether effective treatment would reduce the onset, persistence, and severity of disorders that co-occur with adult ADHD.

Although it has long been known that attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) often persists into adulthood (1 , 2) , adult ADHD has only recently become the focus of widespread clinical attention (3 – 5) . As an indication of this neglect, adult ADHD was not included in either major U.S. psychiatric epidemiological survey of the past two decades, the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study (6) or the National Comorbidity Survey (7) . Attempts to estimate the prevalence of adult ADHD by extrapolating from childhood prevalence estimates linked with estimates of adulthood persistence (8 – 11) and direct estimation in small subject groups (12 , 13) have yielded estimates in the range of 1%–6%. In order to obtain more accurate estimates of prevalence and correlates, an adult ADHD screen was included in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (14) , and clinical reappraisal interviews were carried out with people who had positive results on the screen. These data are used here to estimate the prevalence, comorbidity, and impairment of adult ADHD in the United States.

Method

Sample

As detailed elsewhere (15) , the National Comorbidity Survey Replication is a nationally representative survey of 9,282 English-speaking household residents age 18 or older that was carried out by the professional survey staff of the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan. The response rate was 70.9%. Recruitment featured an advance letter and study fact brochure followed by a visit from an in-person interviewer to answer questions before obtaining verbal informed consent. Consent was verbal rather than written to parallel the procedures of the baseline National Comorbidity Survey (7) for trend comparison. The human subjects committees of Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan both approved these procedures.

The interview was in two parts. Part 1 included a diagnostic assessment administered to all 9,282 respondents. Part 2 included additional questions administered to 5,692 respondents in part 1 who either met the criteria for at least one part 1 disorder or were part of a probability subsample of others. Because of concern about recall failure among older adults, ADHD was assessed in part 2 only among the 3,199 respondents ages 18–44. This sample was weighted to be nationally representative. More details about weighting are reported elsewhere (15) .

The respondents were divided into four strata to select the ones who would receive clinical reappraisal interviews to determine adult ADHD: respondents who denied ever having symptoms of childhood ADHD, those who reported symptoms but did not meet the full criteria for childhood ADHD, those with childhood cases who denied adult symptoms, and those with childhood cases who reported adult symptoms. An attempt was made to contact by telephone 30 respondents in each of the first three strata and 60 in the fourth and to administer a semistructured clinical interview for adult ADHD to them. The final quota sample included 154 respondents (slightly more than the target because more predesignated respondents kept their appointments to be interviewed than expected). The sample was weighted to be representative of the U.S. population in the age range of the sample. Details on the design of the ADHD clinical reappraisal are reported elsewhere (16) .

Adult ADHD

The retrospective assessment of childhood ADHD in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication was based on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (17) . Respondents classified retrospectively as having had ADHD symptoms in childhood were then asked a single question about whether they continued to have any current problems with attention or hyperactivity/impulsivity. The clinical reappraisal interview used the Adult ADHD Clinical Diagnostic Scale version 1.2 (18 , 19) , a semistructured interview that includes the ADHD Rating Scale (20) for childhood ADHD and an adaptation of the ADHD Rating Scale to assess current adult ADHD. The Adult ADHD Clinical Diagnostic Scale has been used in clinical trials with adult ADHD patients (21 , 22) .

Four experienced clinical interviewers (all doctoral-level clinical psychologists) carried out the clinical reappraisal interviews. Each interviewer received 40 hours of training from two board-certified psychiatrist specialists in adult ADHD (L.A., T.S.) and successfully completed five practice interviews. All clinical interviews were tape recorded and reviewed by a supervisor (M.J.H.). Weekly calibration meetings were used to prevent drift. A clinical diagnosis of adult ADHD required six symptoms of either inattention or hyperactivity-impulsivity during the 6 months before the interview (DSM-IV criterion A), at least two criterion A symptoms before age 7 (criterion B), some impairment in at least two areas of living during the past 6 months (criterion C), and clinically significant impairment in at least one of these areas (criterion D). No attempt was made to operationalize the DSM-IV diagnostic hierarchy rules (criterion E).

Comorbid DSM-IV Disorders

Other DSM-IV disorders were assessed in the survey by using the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) version 3.0 (23) , a fully structured lay-administered diagnostic interview. The disorders include anxiety disorders, mood disorders, substance use disorders, and intermittent explosive disorder. Rules involving exclusion of patients with organic causes and diagnostic hierarchy rules were used in making diagnoses. As detailed elsewhere (15) , blinded clinical reappraisal interviews using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (24) with a probability subsample of survey respondents showed generally good concordance of DSM-IV diagnoses based on the CIDI and SCID, with an area under the receiver operator characteristic curve of 0.65–0.81 for anxiety disorders, 0.75 for major depression, and 0.62–0.88 for substance use disorders. The diagnosis of intermittent explosive disorder was not validated, as there is no gold standard clinical assessment for this disorder.

Other Correlates of Adult ADHD

We examined associations of adult ADHD with sociodemographic characteristics and functional disability as assessed with the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (25) . This measure assesses the frequency and intensity of difficulties experienced over the past 30 days in each of three areas of basic functioning—mobility (e.g., walking a mile), self-care (e.g., getting dressed), and cognition (e.g., remembering to do important things)—and three areas of instrumental functioning—time out of role (i.e., number of days totally unable to carry out normal daily activities and number of days of cutting back on amount done or time spent on daily activities), productive role performance (e.g., cutting back on quality of work), and social role performance (e.g., controlling emotions when around other people). Dichotomous measures of disability were defined for each domain by giving equal weights to frequency and intensity of impairments and classifying people with composite scores in the 90th percentile as being disabled. Treatment was assessed in each diagnostic section and in a separate treatment section where we asked about treatment for any emotional or substance use problem. Comparison of responses to the more and less inclusive questions pinpointed people in treatment for comorbid mental or substance-related problems but not for ADHD.

Analysis Methods

Multiple imputation (26) was used to assign predicted diagnoses of clinician-assessed adult ADHD to respondents who did not participate in the reappraisal interviews. As will be detailed, a strong monotonic relationship was found between sampling strata and blinded clinical diagnoses of adult ADHD, justifying this use of multiple imputation. We began by selecting 10 pseudosamples of size 154 with replacement from the 154 respondents in the clinical calibration sample, estimating predicted probabilities of adult ADHD in each sampling stratum of each pseudosample and transforming probabilities to case classifications separately for each case by random selection from the binomial distribution for the predicted probability. These imputations were then used to create 10 separate “data sets” in which substantive analyses were replicated. The parameter estimates in these replications were averaged to obtain multiple-imputation parameter estimates, while parameter variance was estimated by combining the mean within-replication variance with the variance of the parameter estimates across the replications by means of standard multiple-imputation averaging (26) . The increase in variance due to between-replication variance adjusted for the variance introduced by using imputation rather than direct clinical evaluation of all respondents.

Sociodemographic correlates were estimated by using logistic regression analysis, again separately in the 10 multiple-imputation replications. Comorbidity was assessed by obtaining multiple-imputation estimates of odds ratios for the relationship of adult ADHD to other DSM-IV disorders in logistic regression equations that controlled for age in 5-year age groups. Functional disabilities were also estimated by using multiple-imputation logistic regression. Twelve-month treatment was estimated by using multiple-imputation cross-tabulations. Because the sample design used weighting and clustering, all parameters were estimated by using the Taylor series linearization method (27) , a design-based method implemented in the SUDAAN software system (28) . Significance tests of sets of coefficients used Wald chi-square tests based on design-corrected multiple-imputation coefficient variance-covariance matrices. Statistical significance was evaluated by using two-sided design-based tests with an alpha level of 0.05.

Results

Prevalence

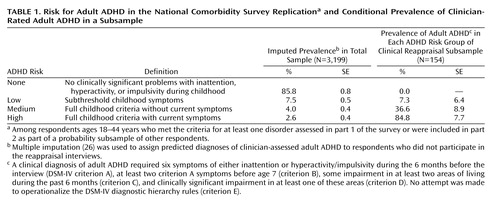

As shown in Table 1 , 85.8% of the respondents reported no clinically significant problems with inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity during their childhoods. Smaller percentages reported subthreshold childhood symptoms, full childhood criteria without current symptoms, and full childhood criteria with current symptoms. A strong monotonic relationship was found between this four-category classification and the blinded clinical diagnoses of adult ADHD based on the reappraisal interviews, with an area under the receiver operator characteristic curve in the weighted clinical calibration sample of 0.86. No false negatives were found among the 85.8% of respondents who reported no childhood symptoms of ADHD, although false negatives were found among the respondents who reported subthreshold symptoms. The estimated prevalence of clinician-assessed adult ADHD in the total sample based on multiple imputation, using a combination of directly interviewed respondents from the clinical reappraisal sample and multiply imputed cases in the remainder of the sample, was 4.4% (SE=0.6). It is noteworthy that exactly the same estimated prevalence and standard error are obtained by using a more conventional two-stage sampling adjustment (29) .

Sociodemographic Correlates

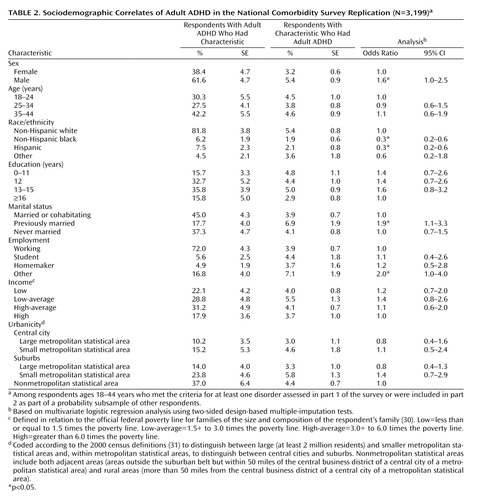

As shown in Table 2 , the multiple-imputation estimates of clinician-assessed adult ADHD were significantly higher among men, non-Hispanic whites (i.e., non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics had significantly lower odds than non-Hispanic whites), the previously married, and people in the “other” employment category (mostly the unemployed and disabled) (30 , 31) . The odds ratios for these predictors were all modest in substantive terms (1.6–3.3).

Comorbidity With Other DSM-IV Disorders

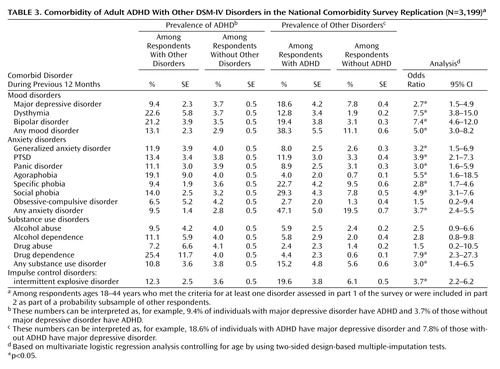

Adult ADHD was significantly comorbid with a wide range of other 12-month DSM-IV disorders ( Table 3 ). The strength of comorbidity did not vary greatly across the disorder classes, with odds ratios of 2.7–7.5 for mood disorders, 1.5–5.5 for anxiety disorders, 1.5–7.9 for substance use disorders, and 3.7 for intermittent explosive disorder.

Basic and Instrumental Functioning

Adult ADHD was associated with significantly elevated odds of disability in all three dimensions of basic functioning assessed by the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule—self-care (2.2), mobility (3.9), and cognition (2.6)—as well as all three dimensions of instrumental functioning—days out of role (2.7), productive role functioning (2.1), and social role functioning (3.5).

Twelve-Month Treatment

A significantly higher proportion of women than men with adult ADHD had received treatment for mental or substance-related problems in the 12 months before the interview (53.1% versus 36.5%, z=2.6, p=0.02). However, only 25.2% of the treated respondents had received treatment for ADHD (22.8% of women and 27.7% of men, z=0.5, p=0.60). Because of this low proportion, only 10.9% of the respondents with adult ADHD had received treatment for ADHD in the 12 months before interview (12.1% of women and 10.1% of men, z=0.4, p=0.66).

Discussion

An important limitation is that the DSM-IV criteria for ADHD were developed with children in mind and offer only minimal guidance regarding diagnosis among adults. Clinical studies make it clear that symptoms of ADHD are more heterogeneous and subtle in adults than children (32 , 33) , leading some clinical researchers to suggest that assessment of adult ADHD requires an increase in the variety of symptoms assessed (34) , a reduction in the severity threshold (35) , or a reduction in the DSM-IV requirement for six of nine symptoms (36) . To the extent that such changes would lead to a more valid assessment than in the current study, our prevalence estimate is conservative.

Three additional limitations are also noteworthy. First, adult ADHD was assessed comprehensively only in the clinical reappraisal subsample. Although the imputation equation was strong, the need to impute entire diagnoses made it impossible to carry out symptom-level investigations of possibilities such as greater prominence of inattentive symptoms, relative to hyperactive/impulsive symptoms, among adults than among children.

Second, both the CIDI and clinical reappraisal interviews were based on self-reports. Childhood ADHD is diagnosed on the basis of parent and teacher reports (37) . Informant assessment is much more difficult for adults, making it necessary to base assessment largely on self-report (38) . Methodological studies comparing adult self-reports and informant reports of ADHD symptoms have documented the same general pattern of underestimation in self-reports by adults as in those by children (39 , 40) , suggesting that our prevalence estimates are probably conservative, although the only study we know of that compared self and informant assessments of adult ADHD in nonclinical subjects showed fairly strong associations between the two reports (41) .

Third, even though the semistructured interview used in the clinical reappraisal interviews, the Adult ADHD Clinical Diagnostic Scale, had been used in clinical studies of adult ADHD, there is no standard method for clinical validation of adult ADHD with the same level of acceptance as the SCID has for anxiety, mood, or substance use disorders, limiting the interpretability of results.

Within the context of these limitations, the results reported document that adult ADHD is common and often produces serious impairment. The 4.4% estimated prevalence is in the middle of previous estimates. This estimate is likely to be conservative for the reasons we have just described. The findings that adult ADHD is associated with unemployment and with being previously married are broadly consistent with results from studies that have documented adverse effects of adult ADHD (8 , 42) . The analyses of responses to the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule are also consistent with this broad pattern. However, the disability results might underrepresent ADHD impairments because some dimensions of the scale tap areas in which ADHD does not produce great impairment (e.g., people with ADHD are often very mobile and overwork) and because the scale does not assess many dimensions in which people with ADHD are thought to function least adequately (e.g., poor sleep and nutrition, accidents, and smoking are common). In addition, as already noted, people with ADHD might have poor insight into their impairments, leading to underestimation of scores on the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule.

The finding of low prevalences among Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks was unexpected. As the DSM-IV ADHD field trials indicated no effects of race/ethnicity (43) , these findings in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication could reflect a race/ethnic difference in adult persistence, in accuracy of adult self-report, in cultural perceptions of the acceptability of ADHD symptoms, or some combination. The finding that adult ADHD is significantly more prevalent among men than women, in comparison, is consistent with much previous research (44) . The 1.6 male-female odds ratio is comparable to the odds ratios found in studies of children and adolescents, suggesting that childhood or adolescent ADHD is no more likely to persist into adulthood among girls than boys (45) . This indirectly suggests that the high proportion of women in adult ADHD patient groups is due to help seeking or recognition bias (46) . The finding that adult ADHD is highly comorbid is consistent with clinical evidence (42) . Methodological analysis has shown that these comorbidities are not due to overlap of symptoms, imprecision of diagnostic criteria, or other methodological confounds (47) .

The average magnitude of the odds ratios reflecting the relationship between adult ADHD and other comorbid disorders is comparable to those for most of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders assessed in the survey (48) . The absence of strong variation in comorbidity odds ratios was surprising, as family studies would lead us to predict high comorbidities with major depression (49) , bipolar disorder (50 , 51) , and conduct disorder (52 , 53) and lower comorbidity with anxiety disorders (54) . One striking implication of the high overall comorbidity is that many people with adult ADHD are in treatment for other mental or substance use disorders but not for ADHD. The 10% of respondents diagnosed with ADHD who had received treatment for adult ADHD is much lower than the rates for anxiety, mood, or substance use disorders (55) . Direct-to-consumer outreach and physician education are needed to address this problem.

The comorbidity findings raise the question of whether early successful treatment of childhood ADHD would influence secondary adult disorders. The fact that a diagnosis of adult ADHD requires at least some symptoms to begin before age 7 means that the vast majority of comorbid conditions are temporally secondary to adult ADHD. We know from the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD that successful treatment of childhood ADHD also reduces childhood symptoms of comorbid disorders (56) . Indirect evidence suggests that stimulant treatment of childhood ADHD might reduce subsequent risk of substance use disorders (57) , although this is not definitive because of possible sample selection bias. Long-term prospective research using quasi-experimental methods is needed to resolve this uncertainty.

A related question is whether adult treatment of ADHD would have any effects on the severity or persistence of comorbid disorders. A question could also be raised as to whether ADHD explains part of the adverse effects found in studies of comorbid DSM disorders. A number of studies, for example, have documented high societal costs of anxiety disorders (58 , 59) , mood disorders (60 , 61) , and substance use disorders (62 , 63) , but these all ignored the role of comorbid ADHD. Reanalysis might find that comorbid ADHD accounts for part, possibly a substantial part, of the effects previously attributed to these other disorders.

Acknowledgments

Collaborating investigators in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication include Ronald C. Kessler (principal investigator, Harvard Medical School), Kathleen Merikangas (co-principal investigator, NIMH), James Anthony (Michigan State University), William Eaton (The Johns Hopkins University), Meyer Glantz (National Institute on Drug Abuse), Doreen Koretz (Harvard University), Jane McLeod (Indiana University), Mark Olfson (Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons), Harold Pincus (University of Pittsburgh), Greg Simon (Group Health Cooperative), Michael Von Korff (Group Health Cooperative), Philip Wang (Harvard Medical School), Kenneth Wells (UCLA), Elaine Wethington (Cornell University), and Hans-Ulrich Wittchen (Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry).

1. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M: Adult outcome of hyperactive boys: educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:565–576Google Scholar

2. Weiss G, Hechtman L: Hyperactive Children Grown Up: ADHD in Children, Adolescents, and Adults. New York, Guilford Press, 1993Google Scholar

3. Pary R, Lewis S, Matuschka PR, Rudzinskiy P, Safi M, Lippmann S: Attention deficit disorder in adults. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2002; 14:105–111Google Scholar

4. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Spencer TJ: Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder across the lifespan. Annu Rev Med 2002; 53:113–131Google Scholar

5. Wilens TE, Faraone SV, Biederman J: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. JAMA 2004; 292:619–623Google Scholar

6. Robins LN, Regier DA (eds): Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

7. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Google Scholar

8. Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K: The persistence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into young adulthood as a function of reporting source and definition of disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 2002; 111:279–289Google Scholar

9. Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV: Age-dependent decline of symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: impact of remission definition and symptom type. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:816–818Google Scholar

10. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M: Adult psychiatric status of hyperactive boys grown up. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:493–498Google Scholar

11. Weiss G, Hechtman L, Milroy T, Perlman T: Psychiatric status of hyperactives as adults: a controlled prospective 15-year follow-up of 63 hyperactive children. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 1985; 24:211–220Google Scholar

12. Murphy K, Barkley RA: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder adults: comorbidities and adaptive impairments. Compr Psychiatry 1996; 37:393–401Google Scholar

13. Heiligenstein E, Conyers LM, Berns AR, Miller MA, Smith MA: Preliminary normative data on DSM-IV attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in college students. J Am Coll Health 1998; 46:185–188Google Scholar

14. Kessler RC, Merikangas KR: The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): background and aims. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2004; 13:60–68Google Scholar

15. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, Demler O, Heeringa S, Hiripi E, Jin R, Pennell BE, Walters EE, Zaslavsky A, Zheng H: The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2004; 13:69–92Google Scholar

16. Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, Demler O, Faraone S, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Jin R, Secnik K, Spencer T, Ustun TB, Walters EE: The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med 2005; 35:245–256Google Scholar

17. Robins LN, Cottler L, Bucholz K, Compton W: Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. St Louis, Washington University, 1995Google Scholar

18. Adler L, Cohen J: Diagnosis and evaluation of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2004; 27:187–201Google Scholar

19. Adler L, Spencer T: The Adult ADHD Clinical Diagnostic Scale (ACDS) V 1.2. New York, New York University School of Medicine, 2004Google Scholar

20. DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulos AD, Reid R: ADHD Rating Scale-IV: Checklists, Norms, and Clinical Interpretation. New York, Guilford Press, 1998Google Scholar

21. Michelson D, Adler L, Spencer T, Reimherr FW, West SA, Allen AJ, Kelsey D, Wernicke J, Dietrich A, Milton D: Atomoxetine in adults with ADHD: two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 53:112–120Google Scholar

22. Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, Faraone S, Prince J, Gerard K, Doyle R, Parekh A, Kagan J, Bearman SK: Efficacy of a mixed amphetamine salts compound in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:775–782Google Scholar

23. Kessler RC, Ustun TB: The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2004; 13:93–121Google Scholar

24. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 2002Google Scholar

25. Chwastiak LA, Von Korff M: Disability in depression and back pain: evaluation of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO DAS II) in a primary care setting. J Clin Epidemiol 2003; 56:507–514Google Scholar

26. Rubin DB: Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York, John Wiley and Sons, 1987Google Scholar

27. Wolter KM: Introduction to Variance Estimation. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1985Google Scholar

28. SUDAAN: Professional Software for Survey Data Analysis. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 2002Google Scholar

29. Shrout PE, Newman SC: Design of two-phase prevalence surveys of rare disorders. Biometrics 1989; 45:549–555Google Scholar

30. Proctor BD, Dalaker J: Current population reports, in Poverty in the United States: 2001. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 2002Google Scholar

31. US Census Bureau: County and City Databook, 2000. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 2000Google Scholar

32. DeQuiros GB, Kinsbourne M: Adult ADHD: Analysis of self-ratings in a behavior questionnaire. Ann NY Acad Sci 2001; 931:140–147Google Scholar

33. Wender PH, Wolf LE, Wasserstein J: Adults with ADHD: an overview. Ann NY Acad Sci 2001; 931:1–16Google Scholar

34. Barkley RA: ADHD Behavior Checklist for Adults. ADHD Report 1995; 3(3):16Google Scholar

35. Ratey J, Greenberg S, Bemporad. JR, Lindem K: Unrecognized attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults presenting for outpatient psychotherapy. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1992; 4:267–275Google Scholar

36. McBurnett K: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a review of diagnostic issues, in DSM-IV Sourcebook, vol 3. Edited by Widiger TA, Francis AJ, Pincus HA, Ross R, First MB, Davis W. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1997, pp 111–143Google Scholar

37. Jensen PS, Rubio-Stipec M, Canino G, Bird HR, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME, Lahey BB: Parent and child contributions to diagnosis of mental disorder: are both informants always necessary? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:1569–1579Google Scholar

38. Wender PH, Wolf LE, Wasserstein J: Adults with ADHD: an overview. Ann NY Acad Sci 2001; 931:1–16Google Scholar

39. Gittelman R, Mannuzza S: Diagnosing ADD-H in adolescents. Psychopharmacol Bull 1985; 21:237–242Google Scholar

40. Zucker M, Morris MK, Ingram SM, Morris RD, Bakeman R: Concordance of self- and informant ratings of adults’ current and childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms. Psychol Assess 2002; 14:379–389Google Scholar

41. Murphy P, Schachar R: Use of self-ratings in the assessment of symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1156–1159Google Scholar

42. Biederman J: Impact of comorbidity in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65(suppl 3):3–7Google Scholar

43. Lahey BB, Applegate B, McBurnett K, Biederman J, Greenhill L, Hynd GW, Barkley RA, Newcorn J, Jensen P, Richters J: DSM-IV field trials for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1673–1685Google Scholar

44. Scahill L, Schwab-Stone M: Epidemiology of ADHD in school-age children. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2000; 9:541–555, viiGoogle Scholar

45. Biederman J, Faraone SV, Monuteaux MC, Bober M, Cadogen E: Gender effects on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults, revisited. Biol Psychiatry 2004; 55:692–700Google Scholar

46. Arcia E, Conners CK: Gender differences in ADHD? J Dev Behav Pediatr 1998; 19:77–83Google Scholar

47. Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A: Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1999; 40:57–87Google Scholar

48. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE: Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:593–602Google Scholar

49. Biederman J, Faraone SV, Keenan K, Tsuang MT: Evidence of familial association between attention deficit disorder and major affective disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:633–642Google Scholar

50. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mennin D, Wozniak J, Spencer T: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder with bipolar disorder: a familial subtype? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:1378–1387Google Scholar

51. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Monuteaux MC: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with bipolar disorder in girls: further evidence for a familial subtype? J Affect Disord 2001; 64:19–26Google Scholar

52. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Jetton JG, Tsuang MT: Attention deficit disorder and conduct disorder: longitudinal evidence for a familial subtype. Psychol Med 1997; 27:291–300Google Scholar

53. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Monuteaux MC: Attention-deficit disorder and conduct disorder in girls: evidence for a familial subtype. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48:21–29Google Scholar

54. Biederman J, Faraone SV, Keenan K, Steingard R, Tsuang MT: Familial association between attention deficit disorder and anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:251–256Google Scholar

55. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:629–640Google Scholar

56. Jensen PS, Hinshaw SP, Swanson JM, Greenhill LL, Conners CK, Arnold LE, Abikoff HB, Elliott G, Hechtman L, Hoza B, March JS, Newcorn JH, Severe JB, Vitiello B, Wells K, Wigal T: Findings from the NIMH Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD (MTA): implications and applications for primary care providers. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2001; 22:60–73Google Scholar

57. Biederman J: Pharmacotherapy for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) decreases the risk for substance abuse: findings from a longitudinal follow-up of youths with and without ADHD. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64(suppl 11):3–8Google Scholar

58. Greenberg PE, Sisitsky T, Kessler RC, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER, Davidson JR, Ballenger JC, Fyer AJ: The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the 1990s. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:427–435Google Scholar

59. Lepine JP: The epidemiology of anxiety disorders: prevalence and societal costs. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63(suppl 14):4–8Google Scholar

60. Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, Leong SA, Lowe SW, Berglund PA, Corey-Lisle PK: The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:1465–1475Google Scholar

61. Rice DP, Miller LS: The economic burden of affective disorders. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1995; 27:34–42Google Scholar

62. Cartwright WS: Costs of drug abuse to society. J Ment Health Policy Econ 1999; 2:133–134Google Scholar

63. Harwood HJ, Fountain D, Fountain G: Economic cost of alcohol and drug abuse in the United States, 1992: a report. Addiction 1999; 94:631–635Google Scholar