Analysis of the Patient-Therapist Relationship in Dynamic Psychotherapy: An Experimental Study of Transference Interpretations

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to measure the effects of transference interpretations (the assumed core active ingredient) in dynamic psychotherapy, using an experimental design. Method: One hundred patients were randomly assigned to two groups. One group received dynamic psychotherapy over 1 year, with a moderate level of transference interpretations, while the other group received dynamic psychotherapy with no transference interpretations. The most common axis I disorders were depression and anxiety disorders. Forty-six patients fulfilled the general criteria for personality disorder. Seven experienced psychotherapists treated patients in both groups. Five full sessions from each treatment were rated by two evaluators with process measures in order to document treatment integrity. Outcome variables were the Psychodynamic Functioning Scales, Inventory of Interpersonal Problems Scale-Circumplex version, Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, and Symptom Checklist-90-R. Quality of Object Relations Scale (lifelong pattern) and personality disorders were preselected as possible moderators of treatment effects. Change was assessed using linear-mixed models. Clinically significant change was also calculated. Results: The authors could not demonstrate differential treatment effects between the groups. However, the moderator analyses showed that transference interpretations were more helpful for patients with a lifelong history of less mature object relations. Small negative effects were observed for patients with mature object relations. Conclusions: The authors could not show differences in average effectiveness between treatments. However, the moderator analyses indicated that treatment worked through different active ingredients for different patients. Contrary to common expectation, patients with poor object relations profited more from therapy with transference interpretations than from therapy with no transference interpretations.

What are the active ingredients in psychodynamic psychotherapy? This question has not yet been addressed with experimental research (1) . It has been a generally held view that transference interpretations are a core active ingredient of psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapy (2 – 4) . However, the technical use of transference interpretations versus other interpretations has been intensively debated over a period of 100 years. Despite this fact, the research base remains very limited and inconclusive. Only one of eight naturalistic studies has reported a positive correlation between transference interpretations and outcome (5) .

The concept of transference was originally observed by Freud as a reconstruction of patients’ repressed historical past “transferred” onto the relationship with the therapist (6) . However, the transference is also influenced by the actual behavior of the therapist (7) . An explicit interpretation of the patient’s ongoing relationship with the therapist is defined as a transference interpretation. Influential theorists (2 – 4) have argued that transference interpretations are compelling when they are accurate. Focus on the transference makes it possible for the patient (and therapist) to become directly aware of the distinction between reality and fantasy in the therapeutic encounter. However, in brief therapy, transference interpretations may be too anxiety-provoking. It is therefore maintained that patients must fulfill criteria of suitability, which generally means that they are able to establish mature interpersonal relationships (8 – 10) .

The alternative to transference interpretation is to interpret conflicts and interpersonal patterns in the patient’s contemporary relationships or memories of past relationships, without including any reference to the patient-therapist interaction (extratransference interpretation). An example of such an interpretation might be, “You feel that your colleague is exploiting you by not doing her share of the work. This may be difficult to tell her directly, so your headache builds up.” On the other hand, almost all of a patient’s associations may theoretically have some meaning in the transference. An example of a transference interpretation of the same material might be, “You told me that your colleague is doing less than her share of the job, which led to a headache that has bothered you since our last session. Could this perhaps also be related to a feeling you have that I do not do my share of the therapeutic work? It may be difficult to say this directly to me.”

Our study is the first experimental investigation designed to measure the effects of a moderate level of transference interpretations in brief dynamic psychotherapy. One hundred patients were randomly assigned to brief dynamic psychotherapy with and without transference interpretations. Since the main goal of exploratory dynamic psychotherapy is to improve interpersonal functioning through better self-understanding and affect tolerance, nonsymptom measures were selected as the primary outcome variables. Our first hypothesis, based on mainstream clinical thinking, was that patients treated with transference interpretations (the transference group) would improve more than patients treated without transference interpretations (the comparison group) on the two primary outcome measures, the Psychodynamic Functioning Scales (11) and Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-Circumplex version (12) . We made no specific prediction with regard to symptom change, measured by the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale and Symptom Checklist 90-R (13) . Our second hypothesis was that highly suitable patients—that is patients with a history of more mature object relations and/or without personality disorders—might do better with transference interpretations.

Method

Patients

The patients were referred to the study therapists by primary care physicians, private specialist practices, and public outpatient departments. None were solicited for research. These patients wanted exploratory psychotherapy because of depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and interpersonal problems. Patients with psychosis, bipolar illness, organic mental disorder, or substance abuse were excluded. Participants were also excluded if mental health problems had caused sick leave for several periods longer than 1 year.

After taking history and assessment of background variables by the patients’ therapists, each patient had a 2-hour psychodynamic interview, modified after Malan (8) and Sifneos (9) , with an independent evaluator. The interview was audiotaped. Several of the other clinicians, including the therapist, listened to the interview. Based on the interview, the Quality of Object Relations Scale (10) , the Psychodynamic Functioning Scales (11) , and the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale were independently rated by at least three clinicians. The patients completed the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-Circumplex version and Symptom Checklist-90-R. No structured interview was used in this study to determine axis I diagnoses. The diagnoses were discussed until consensus was reached, based on all available material, according to the criteria of DSM-III-R. Axis II diagnoses were determined by the patients’ therapists using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II) (14) . All the therapists had prior training in using SCID-II. In addition, the general diagnostic criteria for (any) personality disorder (DSM–IV, p. 633) were discussed in each case, based on all available material, until consensus was reached.

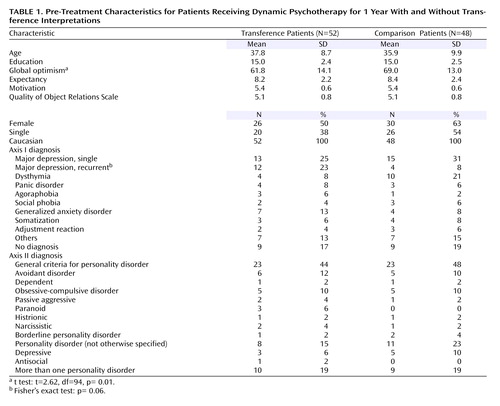

After the procedures had been fully explained, written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Fifty-two patients were assigned to dynamic psychotherapy with a low to moderate use of transference interpretations (the transference group). Forty-eight patients were assigned to dynamic psychotherapy of the same kind but without transference interpretations (the comparison group). The patients were not informed about which technique was studied and the hypotheses of this study. Standard power calculation (endpoint analysis) indicated that moderate effect sizes (effect size: 0.55) could be detected for alpha levels of 0.05 with a power of 0.80. An alpha level of 0.10 was decided for the moderator analyses and the subgroup analyses in order to balance the risk of type II errors. Table 1 presents the pretreatment patient characteristics and shows that the random assignment procedure was successful—that is, we could demonstrate no differences between the groups on the pretreatment variables, including demographic, diagnostic, initial severity, personality, motivation, and expectancy. Patients in the comparison group rated themselves as somewhat more optimistic on a visual analogue scale (0–100 mm). In both groups, patients reported that their main target problem lasted, on average, approximately 9 years. One year after the start of therapy, the patients were interviewed again by a blind, independent clinician.

Therapists and Evaluators

Patients were assigned to one of the seven therapists, depending on availability. The clinical evaluators and therapists consisted of six psychiatrists and one clinical psychologist, all of whom had 10–25 years of experience in practicing psychodynamic psychotherapy. Four of them were certified psychoanalysts. In the pilot phase of this study, the therapists were trained for as long as 4 years in order to be able to administer treatment with a moderate frequency of transference interpretations (1–3 per session) as well as treatment without such interpretations with equal ease and mastery. Each therapist treated from 10 to 17 patients in the main study. All therapists treated patients from both groups. Since the therapists were not blind to the group to which their patients belonged and also served as clinical evaluators of other patients, no therapist ratings (a therapist rating his or her own patients) were included in any of the statistical analyses.

The random assignment of patients was conducted after the pretreatment ratings were completed. Only the patients’ therapists learned the result of the random assignment procedure. The random assignment code was kept on a separate computer, which belonged to our research assistant. The other clinicians remained blind to the group to which the patient belonged. Before the posttreatment evaluation, three of the clinicians rated two audiotaped sessions from each of the first 30 patients regarding treatment fidelity. The raters may have guessed from the content the group in which the patient belonged. We believe that remembering group assignment from listening to anonymous audio tapes weeks or months before the posttreatment evaluation is very unlikely. We cannot, however, maintain that it never happened. For some patients, blinding may have been compromised.

Treatments

The patients were offered 45-minute sessions weekly for 1 year. All sessions were audiotaped. One patient assigned to the comparison group withdrew from the study after the random assignment. Four patients, all of them in the comparison group, dropped out of therapy before session 15. Treatment length, without the dropouts, was equal in the transference and comparison groups (34 [SD 6.1] and 33 [SD 6.6] sessions on average).

A treatment manual for this study was published in 1990 (15) . A different manual for process ratings of audiotaped sessions included the following scales: General Interpersonal Skill, Interpretive and Supportive Technique Scale (16) , and Specific Transference Technique Scales (Høglend 1995, unpublished manual). All items from these scales have similar rating instructions and format (i.e., Likert scales of 0–4).

For the transference group, the following specific techniques were prescribed:

1) The therapist was to address transactions in the patient-therapist relationship.

2) The therapist was to encourage exploration of thoughts and feelings about the therapy and therapist.

3) The therapist was to include himself explicitly in interpretive linking of dynamic elements (conflicts), direct manifestations of transference, allusions to the transference, and repercussions on the transference by high therapist activity.

4) The therapist was to encourage the patient to discuss how he or she believed the therapist might feel or think about him or her.

5) The therapist was to interpret repetitive interpersonal patterns (including genetic interpretations) and link these patterns to transactions between the patient and the therapist. In the comparison group these techniques were proscribed. In this patient group, the therapist consistently used material about interpersonal relationships outside the therapy as the basis for similar interventions (extratransference interpretations).

On average, four or five full sessions from each therapy were rated by three of the clinicians, who were blind to the group to which the patient belonged (sessions N=447). With two raters per session, interrater reliability coefficients were generally high, from 0.70 to 0.97, for all the process scales (17) . The specific transference techniques (five items) differentiated significantly between the treatment groups. The level in the transference group was 8.1 (SD=3.2) versus 0.9 (SD=1.1) in the comparison group (t=15.2, df=64, 90, p<0.0005). Termination of therapy was addressed and interpreted in both groups. Analysis of other interpersonal relationships (extratransference) (five items) was given more space and emphasis in the comparison group. The level was 13.5 (SD=1.6) in the comparison group versus 12.0 (SD=1.6) in the transference group (t=4.6, df=94, p<0.0005). We could detect no differences in the levels of the scales of General Interpersonal Skill (eight items) and Supportive Interventions (seven items) between the two treatment groups.

Both treatments were mainly exploratory in nature. We performed several linear mixed-model analyses with time, time x treatment, therapist, and time x treatment x therapist as fixed effects. We could not detect any significant therapist effects. It should be noted, however, that this study did not have the power to detect any small or moderate therapist x treatment interactions.

Measures

Since none of the instruments for measuring clinician-rated psychodynamic changes was considered sensitive enough to capture statistically significant changes during brief therapy, the Psychodynamic Functioning Scales were developed in the pilot phase of this study (11) . The six scales have the same format as the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale and measure psychological capacities over the last 3 months. These scales are as follows: quality of family relationships, quality of friendships, quality of romantic/sexual relationships, tolerance for affects, insight, and problem solving capacity. Aspects of content validity, internal domain construct validity, interrater reliability, discriminant validity from symptom measures, and sensitivity for change in brief dynamic psychotherapy were tested (11 , 18 , 19) . With at least three clinical raters on each evaluation at pretreatment and posttreatment, the interrater reliability estimates for average scores used in this study were approximately 0.90 for the Psychodynamic Functioning Scales and the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale. The total mean score of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-Circumplex version (12) was used to assess patients’ self-reported interpersonal problems. The measure of self-reported symptom distress was the Global Severity Index of the Symptom Checklist-90-R (13) .

Two patient characteristics were chosen a priori as possible moderators of treatment effects (20) : the Quality of Object Relations Scale score and the presence versus absence of personality disorders. The Quality of Object Relations Scale score was determined from the following three 8-point scales: evidence of at least one stable and mutual interpersonal relationship in the patient’s life, history of adult sexual relationships, and history of nonsexual adult relationships. The Quality of Object Relations Scale measures the patient’s lifelong tendency to establish certain kinds of relationships with others, from mature to primitive. Interrater reliability for average scores of three raters was 0.84 in this study. The predetermined cutoff score for high versus low Quality of Object Relations Scale scores was 5.00.

Statistical Analysis

One outlier patient was deleted from all analyses of longitudinal data. It became clear during treatment that the patient abused sedatives and painkillers. The patient was a 3.4 standard deviation or more from the distribution on three of the four outcome variables. Including this case produced significantly poorer goodness-of-fit measures (change in –2 log likelihood). All longitudinal analyses were performed on the sample of 99 patients. We used linear-mixed models to analyze longitudinal data (SPSS version 12.0) (21) . “Subject” was treated as random effect. Time and intercept were treated as both random and fixed effects, while treatment group was treated as fixed effect only. An unstructured covariance matrix provided the best goodness-of-fit measures for the self-report outcome measures, with three data points. For the clinical outcome measures, with only two data points, a variance components covariance matrix was used. The fixed effects were intercept, time, and time x treatment (22) . By using this model, we assumed that group means at baseline were equal by design. The statistical test of a treatment effect is time x treatment. The fixed effects in the moderator analyses were time, time x treatment, moderator, and time x treatment x moderator. In this model, the moderator is time-invariant and may also have an effect at baseline. The statistical test of a moderator effect is time x treatment x moderator.

Clinically significant change has been proposed as a method for reporting results in treatment studies that signify clinically meaningful improvement for the single patient. In this study reliable change was calculated according to formulas from Jacobson and Truax (23) . Cutoff scores for nonclinical samples were calculated based on community samples of subjects who had been screened and found to be asymptomatic (24 , 25) . For the Psychodynamic Functioning Scales and the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, no normative data exist, but a score of 71 or higher is defined in the descriptive levels of the scales as normal functioning. Patients who change more than measurement error and cross the cutoff scores into the distribution of nonclinical samples are changed to a clinically significant degree.

Results

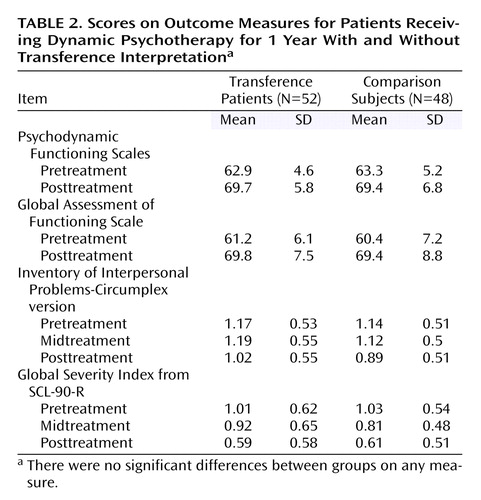

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics over time for the four outcome variables. We could detect no significant differences between the transference group and the comparison group on any of the outcome variables at pretreatment, mid treatment, or posttreatment.

In the mixed-model analyses, time was statistically significant for all outcome variables, with large within-group (pre- to posttreatment) effect sizes. We could detect no statistically significant time x treatment effects.

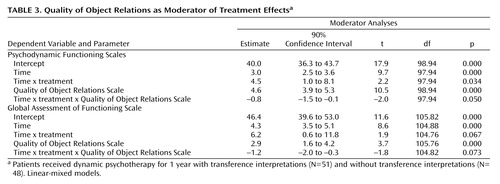

In the moderator analyses, the Quality of Object Relations Scale and personality disorders showed main effects for all outcome variables—that is, the putative moderators also showed an effect at baseline. The Quality of Object Relations Scale was a moderator of treatment effects for the primary outcome variable, the Psychodynamic Functioning Scales, and for the third outcome variable, which was the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale. We could detect no moderator effects for personality disorders. The results of the moderator analyses are shown in Table 3 . Table 3 shows that an effect of treatment emerged when the moderator Quality of Object Relations Scale was included in the statistical model.

Subgroup Analyses

Within the low Quality of Object Relations Scale subsample (N=44), the posttreatment difference on the Psychodynamic Functioning Scales was 3.2 (90% confidence interval [CI]: 0.5–5.8; t=1.79, df=42, p=0.08 [two-tailed]). The effect size (Cohen’s d) (26) was moderate (0.54). The posttreatment difference for the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale was 4.0 (90% CI: 0.2–7.7; t=1.81, df=42, p=0.08 [two-tailed]). The effect size was 0.55. We could not detect any significant posttreatment differences within the high Quality of Object Relations Scale scores subsample (N=55).

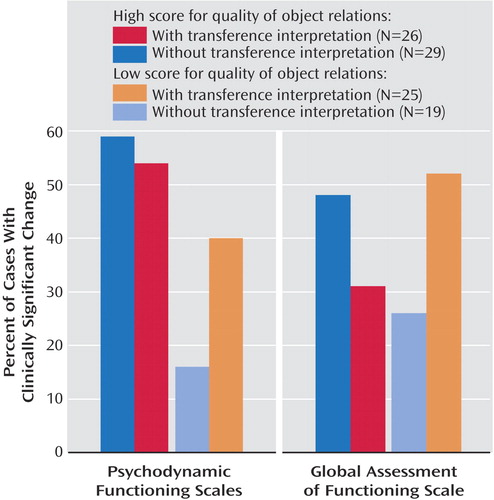

The direction of the interaction effects for the Quality of Object Relations Scale is illustrated in Figure 1 . Within the subsample of patients with low Quality of Object Relations Scale scores, the proportion of patients with clinically significant change was more than twice as high with transference interpretations as with no transference interpretations on all outcome variables. Within the high Quality of Object Relations Scale scores subsample, we could observe only small differences in the opposite direction.

In the low Quality of Object Relations Scale subsample, five patients showed clinically significant change on both the primary outcome variables after therapy with transference interpretations, and none showed clinically significant change after therapy without transference interpretations (Fisher’s exact, p=0.06).

Discussion

We could detect no significant main effects of treatment in this study. Equal average outcomes are typical when different psychotherapies are compared. This has led many researchers to conclude that technical differences between treatments have negligible effects (27) . However, two treatments may be, on average, equally effective but might work through different active ingredients in different patients (20) . The Quality of Object Relations Scale was a moderator of the effects of transference interpretations. Contrary to mainstream clinical thinking and our second hypothesis, transference interpretations were most effective with so-called less suitable patients—that is, patients with low Quality of Object Relations Scale scores. We observed only small nonsignificant negative effects within the high Quality of Object Relations Scale scores subsample.

We could not document that personality disorders were a moderator of treatment effects. It should be noted, however, that within the low Quality of Object Relations Scale subsample, 60% of the patients in both treatment groups had one or more personality disorders, relative to 20% in the high Quality of Object Relations Scale scores subsample.

The moderator effects of the Quality of Object Relations Scale cannot be explained by pretreatment differences between the patient groups, and we could detect no such differences. Eleven patients in the transference group (21%) and nine patients in the comparison group (19%) were treated with antidepressant medication during therapy. Medication was used only for some patients with more severe depression or anxiety, and thus was associated with a slightly worse treatment outcome. Use of medication was well balanced across the two treatments and the subgroups and did not explain or change the results reported in this study.

In an earlier quasi-experimental study from our research group, 43 patients were treated with the following two forms of brief dynamic psychotherapy: high and low in transference interpretations (28) . That study reported a negative effect of high frequency transference interpretations in patients with high quality of interpersonal relationships, a finding which is consistent with some of the observations in this study, and a large-scale naturalistic study by Piper and colleagues (29) . In our previous study, we could not determine whether a low frequency of transference interpretations was favorable within the low quality of interpersonal relations sample, since there was no comparison group treated without transference interpretations. Of eight naturalistic studies (29 – 36) , four report that the Quality of Object Relations Scale was a moderator of negative associations between frequency of transference interpretations and outcome (29 , 34γ6) . To our knowledge, no study reports that personality disorder is a moderator. One might speculate that this could be the case because the Quality of Object Relations Scale covers the range from primitive to superior functioning, whereas personality disorder is a measure of psychopathology only.

An early finding of the Menninger project (37) indicates that patients with ego weakness responded better to expressive psychotherapy with transference interpretations rather than to supportive psychotherapy based on psychoanalytic principles. Clarkin and colleagues later developed a treatment manual for borderline disorder patients (38) . They advocate immediate and persistent interpretation of transference phenomena. Our findings may, to some extent, support their position. Gabbard and colleagues (39) studied session material from three borderline patients in long-term psychotherapy. They suggest that transference interpretations may result in substantial improvements in a patient’s ability to cooperate but also may produce marked deterioration in collaboration.

Limitations

We do not know whether our findings can be generalized to long-term psychotherapy and psychoanalysis. In our study, treatment was manualized and monitored. More individually tailored treatments might have yielded somewhat different effects. However, experimental manipulation of treatment techniques is the only method available, to date, for studying causal effects. The sample size was not large enough to provide accurate estimates of effect sizes, and the population estimates may range from small to large. The therapists were specifically trained over a long period in order to be able to perform both treatments equally well. This is excellent for the internal validity of the study but less than optimal for the generalizability to standard practice. However, despite the long training period, we cannot rule out with absolute confidence the possibility that the study therapists were somewhat more comfortable using transference interpretations.

Conclusion

Analysis of transference aims to improve interpersonal functioning. Transference interpretations seem to be especially important for patients with long-standing problematic interpersonal relationships. Specifically, those patients who need to improve the most benefit the most. Our study needs replication with different groups of patients and therapists. It remains to be seen whether patients with high Quality of Object Relations Scale scores may benefit from transference interpretations in long-term intensive therapy.

1. Leichsenring F, Rabung S, Leibing E: The efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy in specific psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:1208–1216Google Scholar

2. Strachey J: The nature of the therapeutic action of psycho-analysis. Int J Psychoanal 1934; 15:127–159Google Scholar

3. Gill MM: Analysis of Transference. New York, International Universities Press, 1982Google Scholar

4. Gabbard GO, Westen D: Rethinking therapeutic action. Int J Psychoanal 2003; 84:823–841Google Scholar

5. Høglend P: Analysis of transference in psychodynamic psychotherapy: a review of empirical research. Can J Psychoanal 2004; 12:279–300Google Scholar

6. Freud S: Fragments of an analysis of a case of hysteria (1905), in The Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Standard Edition, vol 1. Edited by Stratchey J. London, Hogarth Press, 1953, pp 3–122Google Scholar

7. Gabbard GO: Psychodynamic Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. Arlington, Va, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2000Google Scholar

8. Malan DH: The Frontier of Brief Psychotherapy: An Example of the Convergence of Research and Clinical Practice. New York, Plenum, 1976Google Scholar

9. Sifneos PE: Short-Term Anxiety-Provoking Psychotherapy: A Treatment Manual. New York, Plenum, 1992Google Scholar

10. Høglend P: Suitability for brief dynamic psychotherapy: psychodynamic variables as predictors of outcome. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993; 88:104–110Google Scholar

11. Høglend P, Bøgwald KP, Amlo S, Heyerdahl O, Sørbye O, Marble A, Sjaastad MC, Bentsen H: Assessment of change in dynamic psychotherapy. J Psychother Pract Res 2000; 9:190–199Google Scholar

12. Alden LE, Wiggins JS, Pincus AL: Construction of circumplex scales for the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems. J Pers Assess 1990; 55:521–536Google Scholar

13. Derogatis LR: SCL-90-R: Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual II. Towson, Md, Clinical Psychometric Research, 1983Google Scholar

14. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–III–R Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Arlington, Va, American Psychiatric Publishing, 1990Google Scholar

15. Høglend P: Dynamisk kortidsterapi (Brief dynamic Psychotherapy), in Poliklinikken Psykiatrisk Klinikk 25 år. Edited by Alnes R, Ekern P, Jarval P. Oslo, Universitetet i Oslo, Norway: Psykiatrisk klinikk Vinderen, 1990, pp 27–38Google Scholar

16. Ogrodniczuk JS, Piper WE: Measuring therapist technique in psychodynamic psychotherapies: development and use of a new scale. J Psychother Pract Res 1999; 8:142–154Google Scholar

17. Bøgwald KP, Høglend P, Sørbye O: Measurement of transference interpretations. J Psychother Pract Res 1999; 8:264–273Google Scholar

18. Bøgwald KP, Dahlbender RW: Procedures for testing some aspects of the content validity of the Psychodynamic Functioning Scales and the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale. Psychother Res 2004; 14:453–468Google Scholar

19. Hersoug AG: Assessment of therapists and patients’ personality: relationship to therapeutic technique and outcome. J Personality Assess 2004; 83:191–200Google Scholar

20. Kraemer HC, Wilson T, Fairburn CG, Agras WS: Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:877–883Google Scholar

21. SPSS Inc: Advanced Models 12.00. Chicago, SPSS Inc, 2003Google Scholar

22. Fitzmaurice G, Laird N, Ware J: Applied Longitudinal Analysis. New York, John Wiley and Sons, 2004, pp 122–132Google Scholar

23. Jacobson NS, Truax P: Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991; 59:12–19Google Scholar

24. Tingey RC, Lambert MJ, Burlingame GM, Hansen NB: Clinically significant change: practical indicators for evaluating psychotherapy outcome. Psychother Res 1996; 6:144–153Google Scholar

25. Hansen NB, Lambert MJ: Assessing clinical significance using the inventory of interpersonal problems. Assessment 1996; 3:133–136Google Scholar

26. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1988, pp 20–74Google Scholar

27. Baskin TW, Tierney SC, Minami T, Wampold BE: Establishing specificity in psychotherapy: a meta-analysis of structural equivalence of placebo controls. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003; 71:973–979Google Scholar

28. Høglend P: Transference interpretations and long-term change after dynamic psychotherapy of brief to moderate length. Am J Psychother 1993; 47:494–507Google Scholar

29. Piper WE, Azim HF, Joyce AS, McCallum M: Transference interpretations, therapeutic alliance, and outcome in short-term individual psychotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:946–953Google Scholar

30. Malan DH: Toward the Validation of Dynamic Psychotherapy. New York, Plenum, 1976Google Scholar

31. Marziali EA: Prediction of outcome of brief psychotherapy from therapist interpretive interventions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:301–304Google Scholar

32. Piper WE, Delbane EG, Bienvenu J-P, deCarufel F, Garrant J: Relationships between the object focus of therapist interpretations and outcome in short-term individual psychotherapy. Br J Med Psychol 1986; 59:1–11Google Scholar

33. McCullough L, Winston HA, Farber BA, Porter F, Pollack J, Laikin M, Vingiano W, Trujillo M: The relationship of patient-therapist interaction to the outcome in brief dynamic psychotherapy. Psychother Theory Pract Res Train 1991; 28:525–533Google Scholar

34. Henry WP, Strupp HH, Schacht TE, Gaston L: Psychodynamic approaches, in Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. Edited by Bergin AE, Garfield S. New York, John Wiley and Sons, 1994, pp 467–508Google Scholar

35. Connoly MB, Crits-Christoph P, Shappel S, Barber JP, Luborsky L, Shaffer C: Relations of transference interpretations to outcome in the early sessions of brief supportive—expressive psychotherapy. Psychother Res 1999; 9:485–495Google Scholar

36. Ogrodniczuk JS, Piper WE, Joyce AS, McCallum M: Transference in short-term dynamic psychotherapy. J Nerv Ment Dis 1999; 187:571–578Google Scholar

37. Kernberg OF, Burstein E, Coyne L, Applebaum A, Horwitz L, Voth H: Psychotherapy and psychoanalysis: final report of the Menninger Foundation’s Psychotherapy Research Project. Bull Menninger Clin 1972; 36:1–275Google Scholar

38. Clarkin JF, Yeomans FE, Kernberg OF: Psychotherapy for Borderline Personality. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1999Google Scholar

39. Gabbard GO, Horwitz L, Allen JG, Frieswyk S, Newsom G, Colson DB, Coyne L: Transference interpretation in the psychotherapy of borderline patients: a high-risk, high-gain phenomenon. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1994; 2:59–69Google Scholar