Risk Factors for the Onset of Eating Disorders in Adolescent Girls: Results of the McKnight Longitudinal Risk Factor Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the importance of potential risk factors for eating disorder onset in a large multiethnic sample followed for up to 3 years, with assessment instruments validated for the target population and a structured clinical interview used to make diagnoses. METHOD: Participants were 1,103 girls initially assessed in grades 6–9 in school districts in Arizona and California. Each year, students completed the McKnight Risk Factor Survey, had body height and weight measured, and underwent a structured clinical interview. The McKnight Risk Factor Survey, a self-report instrument developed for this age group, includes questions related to risk factors for eating disorders. RESULTS: During follow-up, 32 girls (2.9%) developed a partial- or full-syndrome eating disorder. At the Arizona site, there was a significant interaction between Hispanics and higher scores on a factor measuring thin body preoccupation and social pressure in predicting onset of eating disorders. An increase in negative life events also predicted onset of eating disorders in this sample. At the California site, only thin body preoccupation and social pressure predicted onset of eating disorders. A four-item screen derived from thin body preoccupation and social pressure had a sensitivity of 0.72, a specificity of 0.80, and an efficiency of 0.79. CONCLUSIONS: Thin body preoccupation and social pressure are important risk factors for the development of eating disorders in adolescents. Some Hispanic groups are at risk of developing eating disorders. Efforts to reduce peer, cultural, and other sources of thin body preoccupation may be necessary to prevent eating disorders.

Full- and partial-syndrome eating disorders affect as many as 10% of adolescent girls and pose a considerable threat to their health and happiness (1). While clinical treatments can be effective, they are expensive and not always available (1). Thus, given the high prevalence of eating disorders, prevention programs are needed (2).

To lay the foundation for prevention programs, a number of potential risk factors for eating disorders have been examined in cross-sectional and prospective studies. Most of these studies have involved predominantly or exclusively white study groups and—at least for the younger samples—have included a restricted set of measures—measures not validated for the targeted age range—and/or used diagnoses derived from paper-and-pencil measures.

Previous studies have also used different methods of defining risk. Kraemer et al. (3) suggested a definition for risk that we employed for this study: “A risk factor is defined as a characteristic, experience or event that, if present, is associated with an increase in the probability (risk) of a particular outcome over the base rate of the outcome in the general (unexposed) population.” They set forth the following requirements for evaluating risk: 1) define the outcome clearly and completely and measure it validly; 2) define the population and sample it properly; 3) define the risk factor, establish that it defines a characteristic that occurs before the outcome, and measure it validly and reliably; 4) use analytic procedures that lead to definitions of high- and low-risk groups and establish that a statistically significant difference exists in the risks of these groups; and 5) use analytic procedures that lead to meaningful demonstrations of potency.

This study was designed to examine the relative importance of many of the potential risk factors for eating disorders by using methods consistent with the risk factor definition and estimation criteria specified by Kraemer et al. (3).

Method

Participants

Participants were 1,358 female students selected from schools in Hayward, Calif., and Tucson, Ariz. The school districts were chosen because of their diverse but relatively stable populations. The school districts preferred—and the human subjects committee approved—the use of passive consent. Parents were mailed a letter informing them of the study and letting them know that their child could be withdrawn from the study by calling the school or returning an enclosed letter. Consent letters were mailed out in English and Spanish. In addition, the students were told that they could withdraw from the study at any time.

Procedures

Data were obtained over a 4-year period. Paper-and-pencil measures, structured clinical interviews, and height and weight measures were administered once a year during the students’ regular classroom periods.

Measures

McKnight Risk Factor Survey IV

The McKnight Risk Factor Survey IV is a revised version of the McKnight Risk Factor Survey III (4). On the basis of test-retest data, a small number of questions were rewritten, added, or dropped from the III version for the IV version. The McKnight Risk Factor Survey IV consists of 103 questions that assess demographics, age at onset of menstrual period and dating, appearance appraisal, effect of body changes, confidence, depressed mood, emotional eating, media modeling, concern with weight/shape, parental and peer concern with thinness, teasing, negative life events, perfectionism, changing eating around peers, substance use, support from others, dieting behaviors, “activities that make you feel good about yourself,” participation in high-risk activities (e.g., cheerleading), perceived mother’s and father’s maximum scores on the Figure Rating Scale of Stunkard et al. (5) (students circled the figure that best looked like the most their biological mother or father had ever weighed), and several miscellaneous items. Most items are scored on a 5-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The items are grouped into domains based on theoretical considerations. (The final instrument with detailed norms and psychometrics, including test-retest reliabilities of items and factors, can be found at http://bml.stanford.edu.)

A principal components analysis was conducted for the domains hypothesized to be risk factors for this age group at baseline. Redundancies were either removed or combined. Domains were listed on the factor with their highest loading; any domain loading below 0.5 was eliminated. At baseline, seven separate factors were identified: 1) thin body preoccupation and social pressure, which includes questions related to media modeling, concern with weight/shape, peer concern with thinness, dieting behaviors, and weight teasing by peers; 2) substance use; 3) parental influences (parent concern with thinness, weight teasing by parents); 4) general psychological influences (appearance appraisal, confidence, depressed mood, social evaluation); 5) social support (supportive people, support sharing); 6) number of negative life events; and 7) school performance. Perfectionism loaded on the same factor with school performance. Because the two measures used different metrics and the perfectionism measure had relatively poor test-retest reliability, school performance was retained and perfectionism was dropped from further analyses.

The final data set used to predict illness onset consisted of eight factors and variables measured at baseline, change in these same eight variables (measured by slope), and five domains also measured at baseline but reflecting events occurring before the baseline assessment (ethnicity, family history of eating disorders, mother’s and father’s scores on the Figure Rating Scale, and maturity—onset of menstrual period).

McKnight Eating Disorder Examination

All students were interviewed by trained interviewers using the McKnight Eating Disorder Examination for adolescents, a semistructured interview based on the Eating Disorder Examination (6).

Interviewers completed diagnostic forms, and coding accuracy was cross-checked by computer algorithms. To determine reliability of the interviewers’ assessment of the individual questions, a random stratified sample of tape-recorded interviews from each site was coded by interviewers from the other site, blind to the original interviewers’ codes. The random sample included equal numbers of girls who were potentially noncases or cases (interviewees who reported at least one eating disorder symptom). Kappa coefficients were determined for each item with more than 10 responses, as follows: objective loss of control (kappa=0.74, N=21), subjective loss of control (kappa=0.84, N=26), vomiting (kappa=1.0, N=73), importance of weight and shape (kappa=0.72, N=71), “weighed less than others thought I should” (kappa=0.56, N=62), “lost a lot of weight in past 3 months” (kappa=0.94, N=64).

The following criteria were used to define clinical or subclinical subjects with eating disorders. Unless noted, subject classification was based on behavior reported during the past 3 months:

1. Clinical illness: DSM-IV diagnostic criteria were used for full-syndrome anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder.

2.Subclinical illness: Students who did not fit the criteria for full-syndrome illness were classified as having the partial syndrome on the basis of these criteria:

a. Partial-syndrome anorexia nervosa: The criteria were the same as for full-syndrome anorexia nervosa, except for the requirement that students missed a menstrual period for 3 consecutive months, which was liberalized to include students who may not have started their periods or may have missed one or two but not three consecutive periods.

b. Partial-syndrome bulimia: Students with this classification engaged in behaviors similar to those with full-syndrome bulimia nervosa but with lower frequency, e.g., reported 1) objective binges (i.e., eating an objectively large amount of food, as judged by the interviewer, with loss of control) at least once a month and 2) one compensatory behavior (vomiting or purging) less than two times per week but at least once per month or 1) subjective binges (eating a large amount of food not deemed as objectively large by the interviewer and having loss of control) at least once per month and 2) one purging behavior at least once per week.

Height/body weight

Standing height was measured by using a portable stadiometer. Weight was determined with the students wearing light indoor clothing without shoes or coats. Body mass index was calculated as kg/m2.

Statistical Methods

Primary analysis of risk factors, based upon the approach advocated by Kraemer et al. (7), proceeded as follows: potential risk factors were ordered temporally (prepuberty, early adolescence, baseline, change from baseline to year 1 to year 2 to year 3). Stability was determined by intraclass correlation coefficients across assessment years. Variables with an R>0.6 were considered stable enough to preclude the use of change variables in prospective risk factor analyses and were not included; i.e., later measures could be well predicted by baseline measures, in which case there was little meaningful variation in change measures. Each remaining variable was separately tested as a possible risk factor for the outcome by using Cox’s proportional hazards model. To avoid type I errors associated with multiple testing, only variables that were significantly related (p<0.01) to the onset of illness were retained as possible risk factors.

Within each time period (e.g., prepuberty, early adolescence, baseline, follow-up interval), risk factors were examined in pairs to determine whether they were independent, proxy, or overlapping risk factors by using the definitions proposed by Kraemer et al. (7). Independent risk factors are risk factors that are uncorrelated, that exert independent effects on the outcome, and for which temporal precedence cannot be established. To avoid problems with multicollinearity, only the best predictor in a pair of overlapping risk factors was considered. The remaining risk factors were then examined across time to determine whether or not variables were independent, mediators, or moderators—again using the definitions of Kraemer et al. (3). A mediator indicates how or why some factor influences an outcome. A moderator indicates on whom or under what conditions a factor influences an outcome.

The potency of continuous measures was determined by using Cohen’s delta effect size (standardized mean difference between groups). Effect sizes of 0.20 are considered small, those of 0.50 medium, and 0.80 large. The potency of binary measures was determined with natural log odds ratios.

Our second analytic objective was to explore the development of an algorithm enabling clinicians to identify those at greater risk of developing eating disorders. For this purpose, signal detection methods were used.

Results

Baseline Description

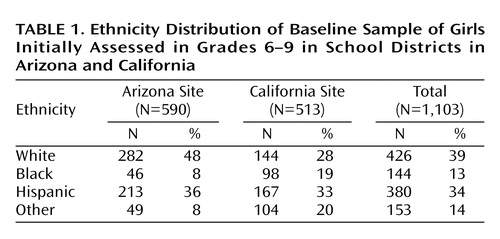

Of the 1,358 girls at baseline, 34 (2.5%) already had a full- or partial-syndrome eating disorder diagnoses and were omitted from this analysis. (Of these, five were diagnosed as having bulimia nervosa, 16 with partial-syndrome bulimia, eight with binge eating disorder, and five with partial-syndrome anorexia.) A total of 221 girls were assessed at baseline only and thus were not available for longitudinal analyses. The percentages of students available at 1, 2, and 3 years for follow-up for the Arizona and California sites, respectively, were 80%, 66%, and 60% and 79%, 69%, and 60%. The ethnic distribution by site for the remaining 1,103 girls can be seen in Table 1.

There were no significant differences in dropout rates between girls from the two sites. Dropouts from the study were more likely to be African American (χ2=8.8, df=1, p<0.01), to use illegal substances (t=5.0, df=1310, p<0.001), to have more negative life events (t=3.8, df=1310, p<0.001), and to be less successful in school (χ2=22.7, df=3, p<0.001). There were no differences between the two groups on other measures.

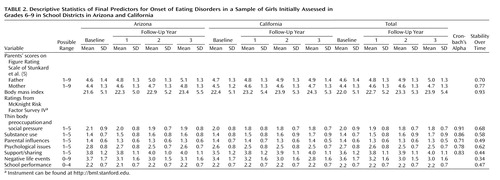

The baseline and follow-up scores for the predictor variables for the Arizona and California samples can be seen in Table 2.

Stability of Baseline Measures

Table 2 shows the stability analysis for the variables measured across time. Five variables (body mass index, thin body preoccupation and social pressure, general psychological issues, and mother’s and father’s scores on the Figure Rating Scale) had stability scores >0.6. Therefore, the corresponding change variables were not included in the risk factor analysis.

Incidence of Eating Disorders

During the course of follow-up, 32 (2.9%) of the 1,103 girls developed a partial- or full-syndrome eating disorder and were classified as follows: one as having bulimia nervosa, 26 with partial-syndrome bulimia, and five with binge eating disorder. There were no new-onset cases of either anorexia nervosa or partial-syndrome anorexia. Nineteen of the new-onset cases were identified at the Arizona site and 13 at the California site.

Risk Factor Analysis

Because there was a significant site-by-Hispanic-ethnicity interaction (W=7.3, p<0.01) for survival, the two sites were analyzed separately.

Arizona site

In this sample, 19% (N=112) of 590 students developed eating disorders. Potential risk factors for the 19 new-onset cases were Hispanic ethnicity (W=6.5, p<0.01), thin body preoccupation and social pressure (W=17.4, p<0.0001), general psychological influences (W=9.8, p<0.01), and change in reported negative life events (W=9.1, p<0.01).

Thin body preoccupation and social pressure and general psychological influences occurred in the same time period and were examined in a pairwise analysis. These variables were significantly correlated (R=0.66, p<0.001) and, when entered into the model together, general psychological issues was no longer significantly related to time to onset, whereas thin body preoccupation and social pressure remained a significant predictor of time to onset (W=7.3, p<0.01). This result suggested that general psychological issues was a proxy for thin body preoccupation and social pressure and could be dropped from further risk factor analyses for this sample.

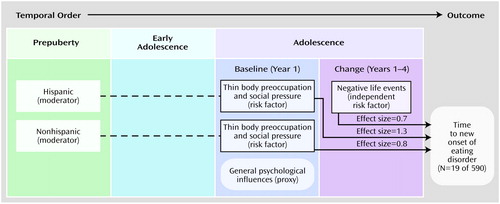

The remaining variables (being Hispanic, thin body preoccupation and social pressure, change in number of negative life events) were then examined in pairs on the basis of temporal sequence. Change in negative life events was found to be an independent risk factor, as it was not correlated with being Hispanic or thin body preoccupation and social pressure. Subjects with new onset showed an increase in negative life events (mean=0.39, SD=1.2), whereas noncases showed a decrease (mean=–0.25, SD=1.0; effect size for differences=0.65). There was a significant interaction effect between being Hispanic and thin body preoccupation and social pressure (W=9.7, p<0.01), indicating that being Hispanic moderates thin body preoccupation and social pressure. To further explore this issue, we looked at the mean scores for thin body preoccupation and social pressure in Hispanic cases and noncases: 68% of the subjects were Hispanic, whereas Hispanics were only 35% of the noncases. New-onset Hispanic subjects scored 3.2 (SD=0.9) on thin body preoccupation and social pressure compared to 2.1 (SD=0.8) for Hispanic noncases (effect size for differences=1.3). For non-Hispanics, new-onset subjects scored 2.7 (SD=0.5) compared to 2.1 (SD=0.9) for noncases (effect size=0.7). The final model can be seen in Figure 1.

California site

The same analytic approach was used for the California data. In this sample, 13 of 513 students developed eating disorders. Only thin body preoccupation and social pressure (W=15.0, p<0.0001) was significantly related to outcome. New-onset subjects scored 3.0 (SD=0.7) compared to 1.9 (SD=0.8) for noncases (effect size for differences=1.2).

Risk Factor Screen

To determine which items from thin body preoccupation and social pressure might be used to screen for potential cases, all five domain scores for thin body preoccupation and social pressure and all questions for these domains were entered into a signal-detection analysis. Each domain and question score was treated as a test for illness and evaluated across a range of cutoff points to determine the variables that would produce an optimally efficient test.

The analysis identified three criteria derived from four questions (each question was scored 1–5): “How often have you been on a diet to lose weight?” (score of 4 or 5); “How often does your weight make boys not like you?” (score of 5); and the average of “How often do you change your eating around boys?” and “How often do you change your eating around girls?” (mean score ≥3.5). Answers above the cutoff for any of three criteria resulted in a screen sensitivity of 0.72, a specificity of 0.80, and an efficiency of 0.79. The predictive value of a positive test was 0.10 (of a base rate of cases of 2.9%), and the predictive value of a negative test was 0.99 (of a base rate of noncases of 97.1%). In this sample, the screen selected 242 students as being possibly at risk (21.9% of the total). Of these, 23 (10%) would become new cases.

Discussion

Higher scores on a factor (thin body preoccupation and social pressure) measuring concerns with weight, shape, and eating (including media modeling, social eating, dieting, and weight teasing) significantly predicted onset of eating disorders in young women in middle and high school. For instance, of those scoring in the upper quartile of this factor (mean >2.4), 8% developed new-onset eating disorders over the course of follow-up compared to 1.2% in the lower three quartiles. In the Arizona sample but not the California sample, thin body preoccupation and social pressure was moderated by ethnicity (Hispanic). An increase in negative life effects was also an independent risk factor in the Arizona sample. Our results also indicated factors that did not predict onset of eating disorders in multivariate analyses, including parental influences, social support, perfectionism/school performance, perceived parental weight, or having an early start of menstrual periods.

The finding that a factor reflecting high weight/shape and other concerns and issues (including dieting) predicts onset of eating disorders is consistent with other recent longitudinal studies in less diverse populations (8, 9). The use of the principal components analysis combines domains (such as dieting and weight concerns) that, in univariate analyses, have been found to be important. An important next step in this area of research is to begin to examine the interactions among the components of thin body preoccupation and social pressure, developmental issues and methods of reducing weight/shape concerns, and dieting.

The finding that being Hispanic moderated the onset of eating disorders at the Arizona but not the California site raises an important issue. Smolak and Striegel-Moore (10) argued that one of the reasons for the often inconsistent findings concerning ethnicity and eating problems is that ethnicity is actually a summary variable capturing diverse experiences and elements such as immigration status, gender roles, discrimination, socioeconomic disparities, and acculturation. The Hispanic girls in Arizona may have differed from those in California on one or more of these factors. For instance, the California girls had higher rates of non-English-speaking households (50% versus 35%, respectively) (χ2=9.3, df=1, p<0.01) and were more likely to identify themselves as being Latin American (44%) compared to the Arizona girls (19% Latin American). Such factors need to be explicitly investigated in future research (11, 12).

More puzzling, perhaps, is the failure to find any difference between African American girls and any of the other ethnic groups in terms of eating problems. Studies routinely find African American girls to be more satisfied with their bodies and to show fewer eating problems and disorders than white or Hispanic girls (12). African Americans have lower rates of anorexia nervosa than do white populations, but there may be less of a difference in the disorders involving binge eating (10, 11).

An increase in negative life events was also an independent (but relatively weak) risk factor for onset of illness in Arizona. This finding is consistent with work by Welch et al. (13) and others who found stress to be a risk factor in retrospective analyses.

Although 86% of the sample was available for at least 1 year of follow-up, the relatively large dropout rate suggests that the results must be interpreted with caution.

At the Arizona site, general psychological issues was found to be a proxy for thin body preoccupation and social pressure. At the California site, the general psychological issues factor approached significance in predicting outcome in the univariate analysis (W=3.6, df=1, p=0.058). Many studies have found an association between eating disorders and various psychological factors, such as negative affect. Stice (14) argued that eating disorders can develop through two pathways—by means of excessive dieting or negative affect. In our model, negative affect (as reflected by self-reported depression) is subsumed under general psychological influences as part of a proxy variable for weight/shape issues.

The power of our analysis was restricted by the low incidence of new cases. However, the incidence of new cases is similar to what has been reported in other populations. The incidence of partial- or full-syndrome eating disorders was 3.6%, which is similar to that reported by Lewinsohn et al. (15) and Killen et al. (9).

Of the new cases, most (81%) were of partial-syndrome bulimia nervosa. Only one of the new cases (3%) was of full-syndrome bulimia nervosa; the rest were of binge eating disorder (15%). Although partial-syndrome and full-syndrome eating disorders appear to exist on a continuum, new-onset full-syndrome cases are relatively rare in middle and high school students. We did not identify any new-onset cases of anorexia nervosa or partial-syndrome anorexia—a surprising finding since the peak age at onset of anorexia is during adolescence—but this is consistent with our previous studies (8, 9). A study from Australia (16) found an incidence of 0.5% of partial-syndrome anorexia and no anorexia nervosa in about 2,000 students followed for up to 2 years. Anorexia nervosa or partial-syndrome anorexia are also less prevalent in African American populations, which constituted 13% of our sample.

The stability data also provide a glimpse into the course of potential risk factors. The thin body preoccupation and social pressure factor was very stable throughout the course of the study. This suggests that the attitudes measured by this factor are formed earlier than was measured here.

Adding to the validity of the thin body preoccupation and social pressure risk factor, we compared the thin body preoccupation and social pressure at baseline for the 34 individuals who reported being ill compared to the students who did not have eating disorders. The mean thin body preoccupation and social pressure score was 2.1 (SD=0.9) and 1.9 (SD=0.8) at Arizona and California, respectively, for noncases compared to 2.8 (SD=1.1) and 3.3 (SD=1.0) for cases.

We also found that four questions could be used to identify 80% of the students who would become ill. The screen had moderate levels of sensitivity, specificity, and efficiency and could be used to help identify students at risk.

Implications for Prevention and Research

This study, along with our two previous studies conducted by Killen and colleagues (9, 10), demonstrates that thin body preoccupation and social pressure is the strongest proximal indicator of the onset of eating disorders. This factor appears to be relatively stable from sixth to 12th grade, suggesting that preoccupation with a thin body ideal may emerge earlier than sixth grade. Of note, no new cases of partial- or full-syndrome anorexia nervosa were identified.

For prevention, the data generated a relatively sensitive and specific screen that can be used to identify students who are at risk for eating disorders. Selected prevention programs (those aimed at higher-risk students) could focus on reducing thin body preoccupation and social pressure. Such prevention programs need to be offered to all ethnic groups and must take into account ethnic differences. The apparent early emergence of thin body preoccupation suggests that prevention programs may be offered before the sixth grade. A next step for prevention efforts is to determine what factors contribute to thin body preoccupation and social pressure and what can be done to reduce them.

|

|

Received Oct. 19, 2001; revision received May 31, 2002; accepted Sept. 3, 2002. From the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and the Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine; and the Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson. Address reprint requests to Dr. Taylor, Department of Psychiatry, Rm. 1326, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305-5722; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grants from the McKnight Foundation (95-531) and from NIMH (MH-60453). The McKnight Investigators are (Stanford University): C. Barr Taylor, M.D. (principal investigator), Susan W. Bryson, M.A., M.S., Tamara M. Altman, M.A., Liana Abascal, M.A., Angela Celio, M.A., Darby Cunning, M.A., and Joel D. Killen, Ph.D.; (University of Arizona) Catherine M. Shisslak, Ph.D. (principal investigator), Marjorie Crago, Ph.D., James Ranger-Moore, Ph.D., Paula Cook, B.A., Anne Ruble, B.A., and Maureen E. Olmsted, Ph.D.; consultants: Helena C. Kraemer, Ph.D., and Linda Smolak, Ph.D.

Figure 1. Risk Factors and Moderators for Onset of Eating Disorders in a Sample of Girls Initially Assessed in Grades 6–9 in School Districts in Arizona

1. Agras WS: The consequences and costs of the eating disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2001; 24:371-379Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kreipe RE, Golden NH, Katzman DK, Fisher M: Eating disorders in adolescents: a position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health 1995; 16:476-479Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kraemer HC, Kazdin AE, Offord DR, Kessler RC, Jensen PS, Kupfer DJ: Coming to terms with the terms of risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:337-343Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Shisslak CM, Renger R, Sharpe T, Crago M, McKnight KM, Gray N, Bryson S, Estes LS, Parnaby OG, Killen J, Taylor CB: Development and evaluation of the McKnight Risk Factor Survey for assessing potential risk and protective factors for disordered eating in preadolescent and adolescent girls. Int J Eat Disord 1999; 25:195-214Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Stunkard AJ, Sorensen T, Schulsinger F: Use of the Danish Adoption Register for the study of obesity and thinness, in The Genetics of Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders. Edited by Kety S, Rowland LP, Sidman RL, Matthysse SW. New York, Raven Press, 1983, pp 115-120Google Scholar

6. Cooper Z, Cooper PJ, Fairburn CG: The validity of the Eating Disorder Examination and its subscales. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 154:807-812Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kraemer HC, Stice E, Kazdin A, Offord D, Kupfer D: How do risk factors work together? mediators, moderators, and independent, overlapping, and proxy risk factors. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:848-856Link, Google Scholar

8. Killen JD, Taylor CB, Hayward C, Haydel KF, Wilson DM, Hammer LD, Kraemer HC, Blair-Greiner A, Strachowski D: Weight concerns influence the development of eating disorders: a 4-year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996; 64:936-940Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Killen JD, Taylor CB, Hayward C, Wilson DM, Haydel F, Hammer LD, Robinson TN, Litt I, Varady A, Kraemer H: Pursuit of thinness and onset of eating disorder symptoms in a community sample of adolescent girls: a three-year prospective analysis. Int J Eat Disord 1994; 16:227-238Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Smolak L, Striegel-Moore RH: Challenging the myth of the golden girl: ethnicity and eating disorders, in Eating Disorders: Innovative Directions in Research and Practice. Edited by Striegel-Moore RH, Smolak L. Washington DC, American Psychological Association, 2001, pp 111-132Google Scholar

11. Douchinis J, Hayden H, Wilfley D: Obesity, body image, and eating disorders in ethnically diverse children and adolescents, in Body Image, Eating Disorders, and Obesity in Youth. Edited by Thompson JK, Smolak L. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2001, pp 67-98Google Scholar

12. Striegel-Moore R, Wilfley D, Pike K, Dohm F, Fairburn C: Recurrent binge eating in black American women. Arch Fam Med 2000; 9:83-87Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Welch SL, Doll HA, Fairburn CG: Life events and the onset of bulimia nervosa: a controlled study. Psychol Med 1997; 27:515-522Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Stice E: A prospective test of the dual-pathway model of bulimic pathology: mediating effects of dieting and negative affect. J Abnorm Psychol 2001; 110:124-135Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Lewinsohn PM, Striegel-Moore RH, Seeley JR: Epidemiology and natural course of eating disorders in young women from adolescence to young adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:1284-1292Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Patton GC, Selzer R, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Wolfe R: Onset of adolescent eating disorders: population-based cohort study over 3 years. Br Med J 1999; 318:765-768Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar