Preliminary Evidence of Low Cortical GABA Levels in Localized 1H-MR Spectra of Alcohol-Dependent and Hepatic Encephalopathy Patients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The aim of the study was to compare levels of neuroactive amino acids in the cerebral cortex of healthy subjects, recently detoxified alcohol-dependent patients, and patients with hepatic encephalopathy. METHOD: Metabolite levels were measured in the occipital cortex by using spatially localized 1H-MRS. Five recently detoxified alcohol-dependent and five hepatic encephalopathy patients with alcohol and non-alcohol-related disease were compared with 10 healthy subjects. RESULTS: The combined level of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) plus homocarnosine was lower in the alcohol-dependent and hepatic encephalopathy patients than in the healthy subjects. CONCLUSIONS: The findings suggest that GABA-ergic systems are altered in both alcohol-dependent and hepatic encephalopathy patients.

Adaptive changes in γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) systems contribute to ethanol tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal (1, 2). Clinical studies have shown low plasma GABA levels during withdrawal, although this finding has been inconsistently replicated in studies of GABA levels in cerebrospinal fluid (3, 4).

GABA function has been implicated in hepatic encephalopathy because of the efficacy of benzodiazepine antagonists in ameliorating cognitive impairments related to hepatic encephalopathy (5). However, postmortem studies have revealed no abnormalities in GABA levels (6).

We believe the current study to be the first attempt to measure in vivo abnormalities in the total cortical level of GABA plus homocarnosine in patients with alcohol dependence or hepatic encephalopathy by means of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS).

METHOD

MRS was performed on healthy subjects (N=10), recently detoxified alcohol-dependent patients (N=5), and patients with hepatic encephalopathy (N=5). The healthy subjects had a mean age of 35 years (SD=7). They completed a clinical assessment that excluded current medical, psychiatric, and substance abuse diagnoses; five also completed additional clinical and neuropsychiatric assessments.

Alcohol-dependent patients were recruited from the Substance Abuse Program of the VA Connecticut Healthcare System, West Haven, Conn., and met the DSM-III-R criteria for alcohol dependence on the basis of a structured clinical interview (7). Other than tobacco dependence, they had no other lifetime substance dependence diagnoses. They completed MRS testing 34 days (SD=20) from their last drink. Two patients receiving benzodiazepines were scanned 3 weeks from their last dose. The alcohol-dependent patients had a mean age of 46 years (SD=11), experienced the onset of alcoholism at a mean age of 22 years (SD=9), and had a mean duration of alcoholism of 24 years (SD=6). The mean liver function test values (IU/liter) for the alcohol-dependent patients were as follows: SGOT, 38 (SD=25); SGPT, 45 (SD=42); and γ-glutamyltransferase, 88 (SD=42). The mean values for the healthy subjects were the following: SGOT, 24 (SD=5); SGPT, 28 (SD=6); and γ-glutamyltransferase, 39 (SD=10).

Patients with hepatic encephalopathy were recruited from the Yale New Haven Hospital Section of Gastroenterology. Their mean age was 40 years (SD=6). During the 12-hour fast before MRS testing, lactulose treatment for hepatic encephalopathy symptoms was withheld from four of the five patients. Blood was drawn for determination of ammonia levels within 1 hour of the MRS scan. The mean liver function test values (IU/liter) were as follows: SGOT, 73 (SD=15); SGPT, 79 (SD=12); and alkaline phosphatase, 202 (SD=20).

All subjects gave written informed consent for the study after an interview in which all procedures were fully explained to them. The protocol was approved by the Yale Human Investigations Committee and the Human Subjects Subcommittee of the VA Connecticut Healthcare System.

After MRS the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (8) was administered to assess the relationship of learning and memory to the total level of GABA plus homocarnosine in the occipital cortex within groups. The subjects were asked to repeat a list of 12 words immediately after presentation and 30 minutes later.

Localized 1H-MR spectra were acquired at 2.1 T from a 1.5× 3.0×3.0-cm3 volume in the occipital lobe (9). Metabolites were measured from short-TE spectra following subtraction of the macromolecule spectrum. The total level of GABA plus homocarnosine (10) was measured by using homonuclear editing (9). Each metabolite concentration was determined from signal intensities, expressed as the ratio of the metabolite to creatine (9); the latter concentration was assumed to be 9 mmol/kg.

Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed to compare the occipital cortex metabolite levels of the subject groups. Post hoc Duncan’s new multiple range tests were performed to adjust for multiple comparisons. The relationship between scores on the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test for immediate and delayed recall and the occipital cortex concentration of GABA plus homocarnosine was determined within groups by using Spearman correlations adjusted for multiple comparisons with Bonferroni corrections. The hepatic encephalopathy patients were excluded from this analysis because data were available for only three patients.

RESULTS

Memory impairment appeared to be associated with an abnormal total level of GABA plus homocarnosine. For the alcohol-dependent patients, but not healthy subjects, there was a significant negative correlation (r=–0.96, p=0.02, N=5) between the occipital cortex GABA-homocarnosine level and the score for delayed, but not immediate, recall on the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test.

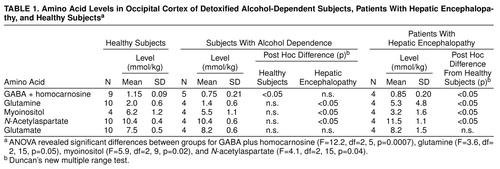

The total GABA-homocarnosine level was lower in the recently detoxified alcohol-dependent and hepatic encephalopathy patients than in the healthy subjects (Table 1). Glutamine and N-acetylaspartate levels were higher and myoinositol levels were lower in the patients with hepatic encephalopathy than in either the healthy subjects or the alcoholics. Venous blood ammonia levels were also higher in the hepatic encephalopathy patients (mean=70 µM, SD=26, N=4) than in the alcohol-dependent (33–42 µM, N=2) or healthy subjects (mean=34 µM, SD=2, N=4). No significant differences emerged in the analyses of glutamate, aspartate, choline (relative to brain creatine), or creatine (relative to brain water).

DISCUSSION

The data show that the total level of GABA plus homocarnosine was low in both the alcohol-dependent patients without clear hepatic injury and the hepatic encephalopathy patients with known liver disease. In the alcohol-dependent patients, the low GABA-homocarnosine level was independent of abnormalities in the levels of the other metabolites measured, suggesting that the abnormalities in the GABA-homocarnosine level do not reflect gross metabolic disturbances or threatened neuronal viability. The low GABA-homocarnosine levels found in this study could contribute to alcohol withdrawal seizures (11)

In contrast to the alcohol-dependent patients, the patients with hepatic encephalopathy had a low GABA-homocarnosine level plus other metabolic abnormalities, such as a high glutamine level and low myoinositol level (12).

Future studies should explore the possibility that low cortical GABA-homocarnosine levels reflect decreased synthesis of GABA and/or homocarnosine.

Received Feb. 18, 1998; revision received Dec. 3, 1998; accepted Dec. 16, 1998. From the Departments of Neurology, Radiology, Internal Medicine, and Psychiatry, Yale University; and the VA-Yale Alcoholism Research Center and VA Connecticut Healthcare System, West Haven, Conn. Address reprint requests to Dr. Behar, MRC, Yale University, P.O. Box 208043, New Haven, CT 06520-8043; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs to the VA-Yale Alcoholism Research Center, grant AA-10121 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Dr. Krystal), grants NS-32126 (Dr. Rothman), NS-32518 (Dr. Petroff), and NS-34813 (Dr. Behar) from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, grant RR-00125 from the National Center for Research Resources (Dr. David Kessler), and grant DK-49230 from the National Institute on Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Dr. Shulman). The authors thank Shela Namanworth and John White for administering neuropsychological evaluations and Terry Nixon and Peter Brown for providing engineering support.

|

1. Ticku MK: Alcohol and GABA-benzodiazepine receptor function. Ann Med 1990; 22:241–246Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Buck KJ, Harris RA: Benzodiazepine agonist and inverse agonist actions of GABAA receptor-operated chloride channels, II: chronic effects of ethanol. J Pharm Exp Ther 1990; 253:713–719Medline, Google Scholar

3. Coffman JA, Petty F: Plasma GABA levels in chronic alcoholics. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:1204–1205Google Scholar

4. Adinoff B, Kramer GL, Petty F: Levels of gamma-aminobutyric acid in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma during alcohol withdrawal. Psychiatry Res 1995; 59:137–144Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Bansky G, Meier PJ, Riederer E, Walser H, Ziegler WH, Schmid M: Effects of the benzodiazepine receptor antagonist flumazenil in hepatic encephalopathy in humans. Gastroenterology 1989; 97:744–750Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lavoie J, Giguere J-F, Layrargues GP, Butterworth RF: Amino acid changes in autopsied brain tissue from cirrhotic patients with hepatic encephalopathy. J Neurochem 1987; 49:692–697Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:624–629Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Brandt J: The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test: development of a new memory test with six equivalent forms. Clin Neuropsychologist 1991; 5:125–142Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Rothman DL, Petroff OAC, Behar KL, Mattson RH: Localized 1H NMR measurements of γ-aminobutyric acid in human brain in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993; 90:5662–5666Google Scholar

10. Rothman DL, Behar KL, Prichard JW, Petroff OAC: Homocarnosine and the measurement of neuronal pH in patients with epilepsy. Magn Reson Med 1997; 32:924–929Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Petroff OA, Rothman DL, Behar KL, Mattson RH: Low brain GABA level is associated with poor seizure control. Ann Neurol 1996; 40:908–911Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Kreis R, Farrow N, Ross BD: Diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Lancet 1990; 336:635–636Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar