Revising and Assessing Axis II, Part II: Toward an Empirically Based and Clinically Useful Classification of Personality Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The DSM-IV classification of personality disorders has not proven satisfying to either researchers or clinicians. Incremental changes to categories and criteria using structured interviews may no longer be useful in attempting to refine axis II. An alternative approach that quantifies clinical observation may prove useful in developing a clinically rich, useful, empirically grounded classification of personality pathology. METHOD: A total of 496 experienced psychiatrists and psychologists used the Shedler-Westen Assessment Procedure-200 (SWAP-200) to describe current patients diagnosed with axis II personality disorders. The SWAP-200 is an assessment tool that allows clinicians to provide detailed, clinically rich descriptions of patients in a systematic and quantifiable form. A statistical technique, Q-analysis, was used to identify naturally occurring groupings of patients with personality disorders, based on shared psychological features. The resulting groupings represent an empirically derived personality disorder taxonomy. RESULTS: The analysis found 11 naturally occurring diagnostic categories, some of which resembled current axis II categories and some of which did not. The findings suggest that axis II falls short in its attempt to “carve nature at the joints”: In some cases it puts patients who are psychologically dissimilar in the same diagnostic category, and in others it makes diagnostic distinctions where none likely exist. It also fails to recognize a large category of patients best characterized as having a dysphoric personality constellation. The empirically derived classification system appears to be more faithful to the clinical data and to avoid many problems inherent in the current axis II taxonomy. CONCLUSIONS: The approach presented here may be helpful in refining the existing taxonomy of personality disorders and moving toward a system of classification that lies on a firmer clinical and empirical foundation. In addition, it can help to bridge the gap that often exists between research and clinical approaches to personality pathology.

Axis II of DSM-IV represents a hybrid of clinical and research observations. The diagnostic categories have their origins in clinical observation and theory, and the categories and criteria have been refined over the years through empirical research. The gradual, empirically based changes in axis II have clearly improved the personality disorder taxonomy. However, they have truly satisfied neither researchers nor clinicians, including members of the DSM-IV task force itself, some of whom have called for the elimination of the current categorical system in favor of a dimensional system (see reference 1).

The methods currently used to revise axis II have a number of limitations. For our purposes, the most important are the following (see also part I of this two-part series).

1. Current personality disorder instruments have significant empirical and conceptual limitations. For example, they have marginal validity and poor retest reliability at intervals greater than 6 weeks. An additional problem is that these instruments do not mirror the assessment procedures used in clinical practice. Clinicians typically assess personality by listening to patients’ narrative accounts of their experiences, noting their behavior in the consulting room, and then making inferences about personality processes. In contrast, current instruments rely on direct questions and expect patients to report on their own personalities. It is highly unlikely that most patients with personality disorders can do so adequately (see part I).

The reliance on such instruments to refine axis II criteria has led to an inversion of the normal procedures for selecting diagnostic criteria. Instead of identifying the best diagnostic criteria and then finding ways to operationalize them, axis II committees have tended to exclude criteria that cannot be assessed by direct questions (for several examples, see reference 2). Thus, we may be limiting the clinical applicability of DSM by linking its refinement so closely to a particular method of assessment.

2. Current instruments are too wedded to the existing taxonomy. The questions included in current assessment instruments are derived from existing diagnostic criteria and therefore are of limited value for developing new or better criteria. Most efforts at refining axis II criteria examine relations between potential new criteria and existing axis II criteria. The problem with this approach is that it assumes we already have the categories and general constellations of symptoms right, since potential criteria are excluded if they do not correlate highly with existing criteria (or if they correlate too highly with criteria for other disorders). Since neither the personality disorder categories nor the constellations of diagnostic criteria were established empirically, and since they typically do not closely match the results of cluster and factor analyses (3, 4), we may at times be refining item sets to fit categories and criteria that exist by convention. With use of current methods for refining axis II, there is no way to solve this problem. Any alternative diagnostic category that better distinguished groups of patients currently classified into existing categories could not be discovered or implemented because its criteria would necessarily overlap with current criteria from other disorders, which may themselves be somewhat arbitrary.

3. The current diagnostic categories do not encompass the domains of functioning relevant to personality. The architects of the DSM system have attempted to avoid diagnostic criteria that are tied too closely to any particular theoretical orientation. This is clearly sensible, since the diagnostic manual must be useable by clinicians of all theoretical orientations. However, it has left axis II committees without guidance regarding the domains of functioning relevant to the concept of “personality.” Personality psychologists continue to debate the precise definition of personality, but most agree it refers to the interaction of enduring patterns of 1) cognition, 2) emotion, 3) motivation, and 4) behavior expressed under particular circumstances (see references 5 and 6). Elsewhere Westen (6, 7) has offered a slightly more differentiated model, arguing that case formulations should address three broad questions: 1) What does the person wish for and fear, and to what extent are these wishes and fears conflicting or unconscious? 2) What psychological resources—cognitive, affective, and behavioral—can the person draw upon to meet internal and external demands? 3) How does the person perceive and experience self and others, and how able is he or she to sustain meaningful and pleasurable relationships?

If the concept “personality” subsumes such domains of functioning, then current axis II criteria for many disorders do not provide even a minimal outline for describing a personality style. Consider, for example, paranoid personality disorder, which is currently defined by the following criteria: fears of deceit or exploitation, fears of betrayal, fears that others will use information against them, fears that people have hidden hostile meanings in their communications, fears that people are attacking them, fears of infidelity, and a tendency to hold grudges against people perceived as having done such things. These criteria are essentially seven indices of a single trait, chronic mistrust. One of them (fear of infidelity) is not empirically related to the disorder but was maintained as a criterion because it seemed to express one more type of malevolent concern (8).

Knowing that a person tends to be distrustful in multiple ways, however, says little about his characteristic ways of thinking (How disordered can his thought become? Is it disordered in noninterpersonal realms as well?), the feelings he typically experiences (Is he sad? Is he shame-prone? Is he anxious?), the ways he deals with those feelings (Does he attempt to manage them by seeking information, by using substances, by turning to a confidante who remains outside his malevolent thought system, by developing grandiose ideas about his place in the world, by projecting his feelings onto others?), what he wishes for in life, what skills he has, how he sees himself, how he spends his time, and so on. Such questions are crucial clinically because they provide insight into the possible functions of the patient’s symptoms, as well as the psychological strengths and weaknesses that bear on the person’s adaptation to life.

4. Axis II criteria are becoming increasingly narrow. Although not the intent of the axis II work groups, the methods used to revise and refine axis II inherently lead to ever-narrower diagnostic criteria, which capture less and less of the richness and complexity of the clinical data. The reasons for this have not, we believe, been adequately appreciated.

Axis II work groups have labored under the constraint of trying to 1) maximize the internal consistency of the diagnostic criteria for each disorder (i.e., the correlations between them) and 2) reduce correlations with criteria for other disorders, while 3) limiting themselves to only seven to 10 diagnostic criteria per disorder. In practice, this means that personality characteristics relevant to multiple disorders must be excluded from all diagnostic categories except one, to avoid problems of comorbidity. For example, lack of empathy was excluded as a criterion for antisocial personality disorder to reduce comorbidity with narcissistic personality disorder, even though research has shown it is one of the most characteristic features of antisocial patients (9).

When diagnostic criteria are revised to increase internal consistency, the result is that the criteria become narrower in scope. This is inevitable, because it is psychometrically impossible for seven to 10 items (criteria) to encompass a complex psychological construct such as a personality disorder and also have high internal consistency. That is why personality researchers do not typically design personality tests with only seven to 10 items. Efforts to maximize the internal consistency of such a small number of diagnostic criteria inherently lead to criteria that are redundant indices of a single trait, not descriptors of a personality configuration. Consider the following: If a personality disorder description should include, at minimum, criteria relevant to a person’s characteristic patterns of 1) thought, 2) affectivity, 3) motivation, and 4) behavior, then an eight-item test will contain, on average, only two items per domain of functioning. Psychometrically, 10 eight-item tests (criteria sets) that each include four two-item “subscales” can never achieve acceptable internal consistency and discriminant validity; no amount of tinkering with the item sets can overcome what is essentially a mathematical impossibility.

OVERVIEW OF THE PRESENT STUDY

The question, then, is how to develop a classification system for personality disorders that is 1) clinically useful and faithful to the data of clinical observation (since ultimately the diagnostic manual must apply to patients in clinical practice), and 2) based on empirical findings so it reflects as accurately as possible the categories of personality dysfunction that occur “in nature.” This article represents one such effort. We report findings based on a large group of personality disorder patients in treatment with an experienced psychiatrist or psychologist drawn from a random national sample. The clinicians described their patients through use of the Shedler-Westen Assessment Procedure-200 (SWAP-200), an assessment tool that allows clinicians to provide detailed and clinically rich psychological descriptions of patients, in a systematic and quantifiable form (see part I). Our aim was to discover whether this information could be used to identify clinically and theoretically meaningful categories of personality disorder patients, without assuming the current axis II taxonomy a priori.

METHOD

Subjects and procedures were the same as those described in part I. A total of 797 experienced psychologists and psychiatrists, drawn from a random national sample, used the SWAP-200 to provide detailed descriptions of actual and hypothetical patients. The study reported here is based on SWAP-200 descriptions of 496 actual patients, diagnosed by their clinicians as meeting axis II criteria for a personality disorder diagnosis. (Hypothetical patients and healthy, high-functioning patients were excluded from the group.)

To identify naturally occurring groupings among the personality disorder patients, we used a procedure known as “Q” factor analysis, or simply Q-analysis. Q-analysis was originally used by biologists conducting taxonomic research, to help classify species. The procedure identifies groups of patients who are similar to one another and dissimilar to patients in other groups. The technique has been used successfully in studies of normal personality (10–16) but not in studies of personality disorders.

Q-analysis can be understood by comparison with conventional factor analysis, which is a common statistical technique in psychological research. Factor analysis is used when a data set contains many variables, and these variables appear to be redundant measures of a few underlying dimensions (factors). The technique identifies groups of variables that are highly similar to one another (i.e., highly correlated) but unrelated to variables in other groups. A researcher can then examine the variables in each group to draw conclusions about the underlying factor that they measure. (For example, if a group contains variables such as “is often sad,” “has little interest in activities,” “cries easily,” and “has suicidal thoughts,” the researcher may conclude that they measure the underlying factor of depression.)

Q-analysis (as used in this study) is computationally the same procedure as conventional factor analysis, except that it creates groupings of similar people, not variables. Thus, Q-analysis identifies groups of patients who share important psychological features that distinguish them from patients in other groups. The groups, called Q-factors, represent empirically derived diagnostic categories that may represent a potential alternative to axis II. (In a typical data file, columns represent variables and rows represent people. Factor analysis identifies columns of data that are similar to one another, whereas Q-analysis identifies rows of data that are similar. The computational procedure is identical, and is accomplished simply by inverting the data matrix [i.e., exchanging rows and columns] before performing calculations.)

The Q-analysis we will present gauges the similarity (or dissimilarity) of patients by the correlation between their SWAP-200 descriptions (see part I). Note that the Q-analysis makes use of all 200 items in the SWAP-200 to gauge the similarity of patients and thus takes account of the configuration of personality characteristics across a broad range of items. The items assess multiple domains of functioning, encompassing characteristic patterns of thought, feeling, motivation, and behavior.

RESULTS

Q-Analysis Procedure

The Q-analysis followed commonly accepted factor analytic procedures; readers familiar with factor analysis will recognize the approach. To determine the number of Q-factors to extract, we performed an initial principle components analysis and retained Q-factors (principal components) with eigenvalues of 1 or higher (Kaiser’s criteria). The procedure resulted in 14 Q-factors, which collectively accounted for 57.2% of the variance in the data set. These Q-factors were then subjected to varimax rotation (i.e., orthogonal rotation, designed to create independent or uncorrelated Q-factors). The first seven of the rotated Q-factors were theoretically coherent and readily interpretable and accounted for 48.4% of the variance in the data set. Thus, we retained these seven Q-factors. Most of the Q-factors included 40 or more patients with factor loadings of 0.50 or higher. The seventh factor was represented by 10 patients, with factor loadings ranging from 0.40 to 0.59. Similar Q-factors emerged when we rotated different numbers of factors, although the solution described here yielded the most clinically coherent findings.

Empirically Derived Diagnostic Categories

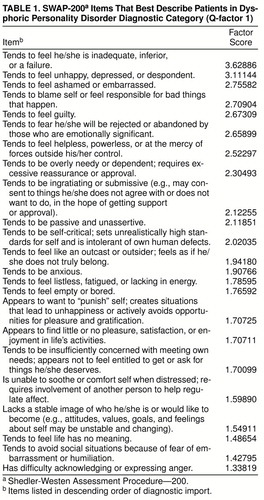

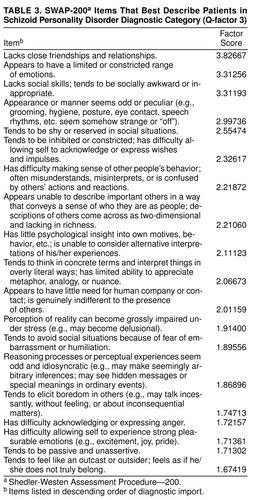

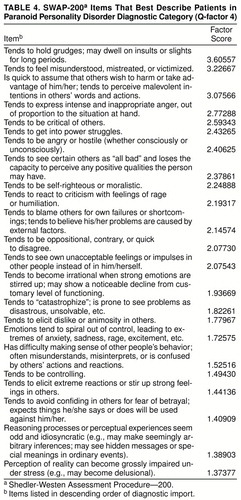

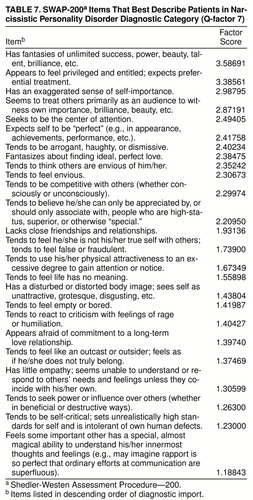

Table 1, table 2, table 3, table 4, table 5, table 6, and table 7 list the SWAP-200 items that best describe the patients in each of the seven Q-factors or diagnostic categories. The second column shows the factor score for each item, which indicates its centrality or importance in defining the Q-factor. (The scores are equivalent to factor scores in conventional factor analysis, except that they apply to items, not subjects.) The items are arranged in descending order of importance, from highest to lowest.

As the items in tables 1 through 7 make clear, there is little doubt about the interpretation of the Q-factors (diagnostic categories) or the appropriate names for them. The results suggest that the Q-analysis identified clinically and theoretically meaningful diagnostic categories.

Several aspects of the Q-factors are worthy of note. First, many of the categories clearly resemble current axis II diagnostic categories. However, the Q-factors have an important advantage over axis II categories, namely, they reflect the empirical solution that maximizes their distinctiveness and minimizes comorbidity. (This result was ensured by the statistical technique used in the Q-analysis, specifically varimax rotation of the Q-factors.) Thus, the typical personality disorder patient will have one personality disorder diagnosis in the empirically derived typology, not the multiple diagnoses common with axis II.

Second, the largest number of patients—over 20% of our group—were classified as belonging in the first Q-factor, which is not in DSM-IV, and which we labeled dysphoric personality disorder. Patients in this Q-factor feel distressed in multiple ways and experience feelings of inadequacy, shame, guilt, depression, anxiety, and fear of rejection or abandonment. The category included many patients diagnosed by their treating clinician as having depressive, dependent, avoidant, self-defeating, or borderline personality disorder. The finding suggests that many patients currently given these diagnoses belong to a single diagnostic group that is characterized by a dysphoric or depressive character structure. Patients in this dysphoric category differ in the activating conditions for their dysphoria (e.g., some become distressed when forced to interact with other people, whereas others become distressed when they feel alone) and in the ways they attempt to regulate it (e.g., by avoiding people and situations, desperately clinging to others, angrily attacking others who frustrate them), but they share the core characteristics of dysphoric affect and self-condemnation.

Third, the Q-analysis treated three sets of disorders differently than axis II, in ways that appear better to “carve nature at the joints.” A single schizoid Q-factor emerged that included many patients currently diagnosed as schizoid and schizotypal, as well as a subset of patients currently diagnosed as avoidant. The distinction between these three disorders has been a matter of controversy since the introduction of axis II, and our data, like those of others (see reference 2), do not support the current taxonomy. Rather, they suggest that these categories do not describe distinct personality styles. A second divergence from axis II was that patients currently diagnosed as borderline tended to fall into either the dysphoric or histrionic Q-factors. This finding directly replicated the results of a pilot study of cluster B disorders (N=153), which used an earlier version of the SWAP (17). A third divergence from axis II was that a large percentage of patients currently diagnosed as having obsessive-compulsive personality disorder appear to be substantially less disturbed than the current axis II conceptualization. These patients resemble Shapiro’s description of the obsessive “neurotic style” (18) more than they resemble the obsessive-compulsive personality disorder of axis II. They are emotionally constricted, prone to intellectualization, and overly concerned with rules, but they are not particularly dysfunctional and they are conscientious and productive to a fault. (We did identify an eighth Q-factor, which we have not presented here because it contained only seven patients of the 496 in the group. Patients in this factor did resemble the DSM-IV description of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, but five of the seven also had an axis I diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder. This suggests that current axis II criteria lead clinicians to confound an axis I syndrome with a personality disorder.)

Subclassifying Within the Dysphoric Category

Because the first Q-factor contained so many patients, we conducted a second Q-analysis to identify subgroups of patients within the dysphoric Q-factor. The Q-analysis paralleled the Q-analysis procedure described earlier. We performed a principal components analysis and retained eight Q-factors (principal components) with eigenvalues greater than 1. These factors were subjected to varimax rotation. The first five of the rotated factors, which together accounted for 51% of the variance, were readily interpretable and retained. Similar factors emerged with five-, six-, and seven-factor solutions, but the five described here proved the most clinically coherent.

Although we will provide only brief descriptions of these subfactors, they represent important subcategories within the dysphoric category. We labeled the first subgroup dysphoric: avoidant. Patients in this category were characterized by SWAP-200 statements indicating (in descending order of importance) that they are shy or reserved, avoid social situations because of fear of embarrassment, lack social skills, are inhibited or constricted, are passive and unassertive, lack close friendships and relationships, feel like outcasts or outsiders, have difficulty allowing themselves to experience strong pleasurable emotions, feel inadequate or inferior, feel ashamed or embarrassed, and are inhibited about pursuing goals or successes (their aspirations or achievements are below their potential).

The second subfactor, which we labeled dysphoric: high-functioning neurotic, was characterized by many SWAP-200 statements indicating psychological strengths, mixed with items indicating chronic dysphoria. The patients’ strengths included being articulate, having high moral and ethical standards, being empathic, appreciating and responding to humor, being conscientious and responsible, being psychologically insightful, tending to elicit liking in others, having the capacity to recognize alternative viewpoints even in matters that stir up strong feelings, being able to hear and benefit from information that is emotionally threatening, and being able to sustain a meaningful love relationship characterized by genuine intimacy and caring. Mixed with these positive items were SWAP-200 items indicating a tendency to blame themselves or feel responsible for bad things that happen; to feel guilty; to seek out or create relationships in which they are in the role of caring for, rescuing, or protecting the other; to feel unhappy, depressed, or despondent; to fear they will be rejected or abandoned; to be self-critical; to be anxious; and to be insufficiently concerned with meeting their own needs.

The third subfactor, which included many patients currently diagnosed as borderline, was labeled dysphoric: emotionally dysregulated. These patients were characterized by SWAP-200 statements describing emotions that spiral out of control, struggles with genuine suicidal wishes, an inability to soothe or comfort themselves when distressed, a tendency to feel life has no meaning, a tendency to make repeated suicidal threats or gestures, a tendency to “catastrophize” (see problems as disastrous and unsolvable), a tendency to become irrational when strong emotions are stirred up, a tendency to feel empty or bored, a tendency to be needy and dependent, and a tendency to engage in self-mutilating behavior.

The fourth subfactor, labeled dysphoric: dependent-masochistic, includes patients who appear to be much more disturbed than those in the current axis II dependent category. These patients tend to get drawn into or remain in relationships in which they are emotionally or physically abused; are ingratiating or submissive; become attached quickly or intensely (develop feelings or expectations that are not warranted by the history or context of the relationship); are suggestible or easily influenced; become attached to, or romantically interested in, people who are emotionally unavailable; are overly needy or dependent; fear being alone; fear they will be rejected or abandoned; express aggression in passive and indirect ways; and lack a stable image of who they are or would like to become.

The final subfactor was labeled dysphoric: hostile-externalizing and contained patients who were hostile and prone to blame others for their difficulties, with passive-aggressive features. The SWAP-200 statements described a tendency to get into power struggles; to be angry or hostile; to blame others for their own failures or shortcomings; to feel misunderstood, mistreated, or victimized; to be critical of others; to be conflicted about authority (to feel they must submit, rebel against, win over, defeat, and so on); to hold grudges; to express aggression in passive and indirect ways; to be oppositional and contrary; and to feel helpless or powerless.

Validity of the Empirically Derived Taxonomy

We created a composite Q-sort description of the patients in each Q-factor, to serve as a diagnostic prototype or template for the Q-factor (see part I). We then computed the correlation between each patient’s SWAP-200 description and each diagnostic prototype, to gauge the “match” between each patient and each Q-factor. We will refer to these correlation coefficients as Q-scores. Thus, each patient received 12 Q-scores, one for each of the seven primary Q-factors and one for each of the five dysphoric subfactors (e.g., a given patient might have a Q-score of 0.44 for the dysphoric Q-factor, –0.06 for the antisocial-psychopathic Q-factor, 0.11 for the schizoid Q-factor, and so on).

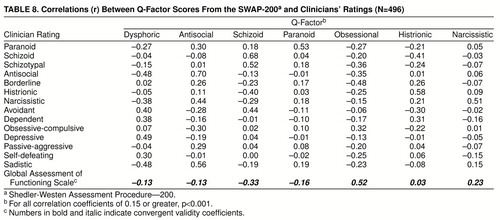

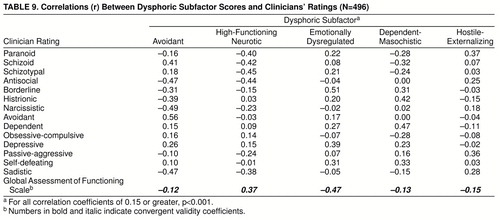

As an initial test of the validity of the new empirically derived personality disorder typology, we examined the relations between Q-scores and clinicians’ ratings of the extent to which patients met current personality disorder criteria (7-point rating scale; 1=“not at all,” 4=“has some features,” and 7=“fully meets criteria”). Because many of the Q-factors are similar to current axis II diagnostic categories, this allowed us to verify, for example, that patients with high Q-scores on our antisocial Q-factor also received high ratings on an independent measure of antisocial personality. Table 8 presents correlations for the primary seven Q-factors, and table 9 presents correlations for the dysphoric subfactors.

As tables 8 and 9 show, Q-scores for categories that resemble current axis II diagnostic (i.e., antisocial, schizoid, paranoid, histrionic, and narcissistic) have uniformly high correlations with clinicians’ ratings for those axis II categories, indicating convergent validity. Of equal importance, the Q-scores had low correlations with clinicians’ ratings for unrelated categories, indicating strong discriminant validity. Note, for example, the distinctiveness of the narcissistic Q-score, which correlates highly with clinician ratings of narcissistic personality disorder (r=0.51) and with nothing else. We are not aware of other personality disorder measures that have been able to distinguish narcissistic personality disorder so clearly from other cluster B disorders, particularly antisocial.

In addition, tables 8 and 9 help us better understand the new diagnostic categories (e.g., dysphoric, and the dysphoric subfactors), relative to the familiar axis II diagnostic categories. As can be seen, patients in the dysphoric Q-factor have avoidant, dependent, and depressive features (and do not have antisocial or narcissistic features); patients in the dysphoric: emotionally dysregulated subfactor have borderline features.

Finally, tables 8 and 9 list the correlations between Q-scores and Global Assessment of Functioning Scale ratings, which were provided by the reporting clinicians. The pattern of correlations indicates that the Q-factors form a hierarchy of pathology, with roughly three levels. In order of increasing pathology, these are 1) narcissistic, obsessional, and dysphoric: high-functioning neurotic; 2) paranoid, antisocial, histrionic, dysphoric, dysphoric: avoidant, dysphoric: dependent-masochistic, and dysphoric: hostile-externalizing; and 3) schizoid and dysphoric: emotionally dysregulated.

DISCUSSION

The SWAP-200 allows clinicians to provide detailed, clinically rich descriptions of patients in a systematic and quantifiable form. These quantified clinical observations may be useful for refining axis II because they generate a classification system that is both empirically grounded and faithful to clinical experience. We identified seven Q-factors or diagnostic categories (or 11, if the dysphoric category is divided into five subcategories), some of which resemble current axis II categories and some of which do not. The psychological features associated with each category appear to be clinically and theoretically coherent, suggesting that the categories represent meaningful clinical syndromes. In addition, the classification system avoids many of the conceptual and empirical problems associated with the current axis II taxonomy (discussed in part I), including 1) unacceptably high comorbidity of personality disorder diagnoses, 2) artificially dichotomizing continuous variables (diagnostic criteria) into present/absent, 3) assuming that personality pathology is categorical, 4) failing to weight criteria that differ in the degree to which they are diagnostic, 5) neglecting healthy aspects of functioning, and 6) lack of fidelity to findings from cluster or factor analytic studies.

Q-scores (which measure the extent to which patients have the characteristics of each Q-factor) correlated in meaningful ways with clinician ratings of the extent to which patients met current axis II diagnostic criteria. Thus, Q-scores correlated highly with clinician ratings for similar axis II diagnoses and did not correlate with ratings for unrelated diagnoses. The pattern of correlations suggests strong convergent and discriminant validity. Indeed, the findings were much stronger than those observed for the current axis II categories (see part I), which is striking since the criterion measures (axis II ratings) were based on current categories. This suggests that our efforts to develop categories with minimal overlap may have been successful; definitive findings in that regard await replication.

A major finding of the study was the emergence of a dysphoric Q-factor, which included roughly 20% of the patient group and was by far the largest category, despite its lack of recognition in DSM-IV. The Q-factor included many patients now diagnosed as dependent, avoidant, depressive, self-defeating, and borderline. The fact that these patients formed a distinct diagnostic category suggests that axis II may have overfocused on the ways such patients are socially dysfunctional and underfocused on the ways in which they are in pain. The data support the inclusion of a depressive/dysphoric personality disorder diagnosis in DSM-V (see reference 19). We also identified distinct subcategories within the dysphoric category. The subcategories encourage a functional approach to understanding personality disorders because they represent not only different triggering conditions for distress (e.g., social interaction versus abandonment) but also different styles of regulating painful affect. Thus, some dysphoric patients respond to pain by self-mutilation or desperately seeking others for soothing (dysphoric: emotionally dysregulated), others become needy and dependent (dysphoric: dependent-masochistic), others avoid interactions that may cause anxiety or feelings of rejection and inadequacy (dysphoric: avoidant), and so on.

A second, and clinically sensible, finding was the identification of a revised schizoid category that includes many patients currently diagnosed as schizoid, avoidant, or schizotypal—three categories that are notoriously difficult to distinguish. The data suggest that these categories are difficult to distinguish because they are not empirically distinct. (The absence of a schizotypal category is worth comment, especially in light of research evidence of the genetic basis of schizotypy. We believe a schizotypal category did not emerge because schizotypy is not a personality disorder [defined by a unique constellation of personality processes] but a clinical syndrome like schizophrenia defined by a single trait [low-grade thought disorder] that might be better diagnosed on axis I. We address this issue in a paper in preparation, in which we isolate a subclinical thought disorder factor through factor analysis, that predicts genetic history of psychosis in first-degree relatives and appears to be taxonic.)

The Q-analysis also identified a revised histrionic diagnostic category that included many items currently in the DSM description of histrionic personality disorder along with several items associated with borderline personality disorder—a category that shows high comorbidity with histrionic personality disorder in all studies of which we are aware. These findings suggest that some patients currently diagnosed with borderline personality disorder may be better classified within the dysphoric spectrum (especially in the dysphoric: emotionally dysregulated category, and to a lesser extent in the dysphoric: dependent-masochistic subcategory), while others may be better diagnosed as histrionic. An important distinction between them is that dysphoric patients’ affective intensity is highly ego-dystonic, whereas histrionic patients’ affective intensity is syntonic. We have now replicated this finding in two independent patient samples (17).

The data also support arguments for a dimensional system for diagnosing personality disorders, either in place of the present categorical system or, probably more useful, in combination with it (20, 21). A dimensional approach would treat personality pathology as a continuum, not as a present/absent dichotomy. Relevant to this is the finding that not all Q-factors were comparable with respect to level of functioning. For example, patients in the obsessional Q-factor and the dysphoric: high-functioning neurotic subfactor were considerably healthier (e.g., had higher Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores) than patients in other categories. Their pathology might better be conceptualized in terms of neurotic styles (17) than in terms of personality disorders. We suspect that in a less constrained patient group, where clinicians described patients with personality pathology but not necessarily axis II disorders, other neurotic styles would appear, such as the hysterical style (17) that influenced the DSM description of histrionic personality disorder but is much more benign. Whether these neurotic styles are simply less severe versions of personality disorders, or represent categories sui generis, is a topic worth empirical attention—especially since over 80% of experienced psychologists and psychiatrists report treating patients for personality pathology not severe enough to warrant an axis II diagnosis [21] and over 60% of patients being treated for maladaptive personality patterns cannot be diagnosed on axis II (22). A Q-analytic study of a group of these patients is currently underway.

Implications

Data such as these need to be replicated and, in particular, need to be replicated in a broader patient group that does not include only patients preselected by clinicians to meet current axis II personality disorder criteria. Instead, the same procedures could be undertaken in a large sample of randomly selected patients being treated for maladaptive personality patterns, who may or may not meet current axis II criteria for a personality disorder. The patients’ SWAP-200 descriptions could then be subjected to Q-factor analysis and subsequently to taxometric analysis (23), to determine what diagnostic categories emerge in a broader sample and whether those categories are true taxons or are better understood as dimensions (continua). An advantage of the Q-factors is that they can be treated as dimensions, categories, or both.

The data also suggest that axis II diagnostic criteria need not be confined to manifestly observable symptoms but should also include criteria that describe personality dynamics underlying these manifest symptoms. For example, if defensive processes can be assessed reliably using jargon-free items that do not require a commitment to a particular theory, then those items should be integrated into diagnostic profiles where they prove diagnostically useful and not relegated to an appendix (16 and 24). The use of such criteria would also increase the clinical usefulness of DSM, since many SWAP-200 items describe psychological processes of this sort that will be addressed in treatment or psychological strengths that clinicians will draw upon in treatment. In contrast, current axis II criteria provide little insight into many treatment-relevant issues (e.g., the function of psychological symptoms, the processes that maintain them, the accompanying affect, the manner of regulating distress).

Perhaps the most important feature of the SWAP-200 method is its potential to bridge the gap that too often separates clinical and empirical approaches to personality pathology. The categories and criteria that emerge through use of the SWAP-200 procedure have clinical validity because they are derived from clinical observation. In addition, they meet or exceed requisite standards for psychometric validity. With the SWAP-200, clinicians do not need to administer a special questionnaire or structured interview to obtain meaningful clinical or research data. They just need to draw appropriate and reasonably straightforward inferences from the clinical data already available to them—which is exactly what well-trained clinicians should be able to do—and express those inferences by using the standard vocabulary of the SWAP-200. Our studies show that clinicians are quite capable of drawing reliable inferences from clinical data, as evidenced by strong correlations between SWAP-200 descriptions of the same patient by independent clinicians (17) and by meaningful patterns of convergent and discriminant validity coefficients.

The SWAP-200 helps bridge the gap between clinical and research approaches in another way, by providing not only diagnostic categories and dimensions, but also narrative case descriptions of patients. To present case formulations, clinicians need only list the 18 to 30 SWAP-200 items placed in the highest categories and use these statements to “anchor” their clinical inferences and formulations (see reference 25). When this procedure is used, case formulation and diagnosis flow from the same procedure and are not the unrelated enterprises that they now tend to be (7).

A Case Example: Using the SWAP-200 to Diagnose an Individual Patient

We now illustrate the use of the SWAP-200 to diagnose an individual patient and also provide a narrative case study. The patient, who we will call Mr. N, was chosen from among the 496 patients in this study. Mr. N is a 48-year-old white man with a college education, seen for nine psychotherapy sessions at the time the treating clinician described him using the SWAP-200. The treating clinician gave him an axis I diagnosis of adjustment disorder and an axis II diagnosis of narcissistic personality disorder. He is relatively high functioning, with a Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score of 65. The clinician reported no noteworthy childhood traumas, although he rated Mr. N’s relationship with his father as very poor. Genetic history is unremarkable.

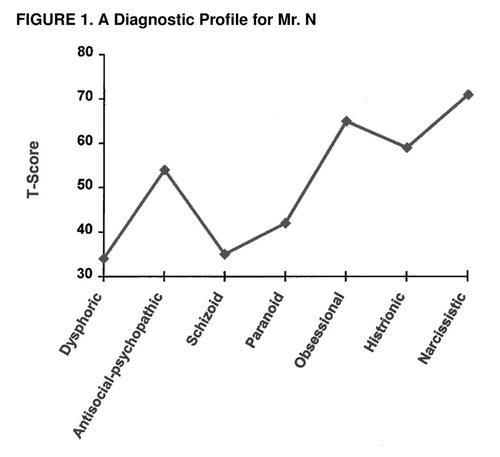

Q-score profile

Figure 1 presents Mr. N’s Q-score profile, showing the match between Mr. N’s SWAP-200 description and each of the seven primary Q-factors. For ease of interpretation, we have transformed the raw Q-scores (which are correlation coefficients) into T scores, which have a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10. (T scores are the metric used by the MMPI and many other psychological tests and are familiar to most personality researchers and many clinicians.) Our data suggest that a T score of 70 or higher (two standard deviations above the mean) is the appropriate cutoff for making a categorical personality disorder diagnosis using the diagnostic categories derived by Q-analysis (which are more distinct than those that describe current diagnoses, as in part I). Thus, Mr. N’s Q-score profile indicates a narcissistic personality disorder with obsessional features. He also appears to have some histrionic qualities.

Narrative description

The reporting clinician placed the following SWAP-200 items in the top three (most descriptive) categories. The items are reprinted nearly verbatim, with only minor grammatical changes to aid the flow of the text.

Mr. N has an exaggerated sense of self-importance; feels privileged and entitled; believes he can only be appreciated by, or should only associate with, people who are high-status, superior, or otherwise “special”; fantasizes about unlimited success, power, beauty, talent, brilliance, and so on; treats others primarily as an audience to witness his importance, brilliance, beauty, etc; seeks to be the center of attention; tends to be arrogant, haughty, and dismissive; and feels an important other has a special, almost magical ability to understand his innermost thoughts and feelings (e.g., he may imagine rapport is so perfect that ordinary efforts at communication are superfluous).

He tends to be angry or hostile (whether consciously or unconsciously), tends to be controlling, and tends to be conflicted about authority (e.g., may feel he must submit, rebel against, win over, defeat). He tends to express aggression in passive and indirect ways (e.g., may make mistakes, procrastinate, forget, become sulky) and to think in abstract and intellectualized terms, even in matters of personal import. He repeatedly convinces others of his commitment to change, only to revert to his previous maladaptive behavior (i.e., he convinces people that “this time is really different”).

Mr. N uses his physical attractiveness to an excessive degree to gain attention and notice; tends to be overly sexually seductive or provocative, whether consciously or unconsciously (e.g., may be inappropriately flirtatious, preoccupied with sexual conquest, prone to “lead people on”); tends to be hostile toward members of the opposite sex, whether consciously or unconsciously; appears afraid of commitment to a long-term love relationship; has an active and satisfying sex life; and fantasizes about finding ideal, perfect love.

Along with his pathology, Mr. N has considerable psychological strengths: He is energetic and outgoing; tends to elicit liking in others; is articulate; appreciates and responds to humor; appears comfortable and at ease in social situations; is creative and able to approach problems in novel ways; can assert himself effectively and appropriately when necessary; and appears to have come to terms with painful experiences from the past, having found meaning in, and grown from, such experiences.

Case formulation

From this configuration of personality characteristics, we draw the following clinical inferences, or hypotheses. Mr. N is a high-functioning narcissistic character. He can be charming and likable and uses his charm to win admiration and affection. At the same time, he is self-centered and entitled and values others primarily to the extent that they bolster his grandiose (but fragile) view of himself (e.g., by offering admiration or witnessing his magnificence). His relationships probably begin with promise, only to sour with time. These personality dynamics find particular expression in Mr. N’s relations with women. We suspect he is a womanizer who leaves victims in his wake, because he is charming and leads women on but is unable to sustain a truly meaningful relationship characterized by mutual empathy, caring, and sharing. He cannot do so because at core he seeks someone whose true role is to help regulate his self-esteem, e.g., by understanding him perfectly, admiring his perfection, and being perfect herself. He is angry and subtly devaluing toward women, who do not quite fulfill these wishes. At age 48, his fantasies about ideal, perfect love are increasingly difficult to sustain. He is probably confused and pained by his repeated failed relationships, and this may be what has brought him to treatment.

If our inferences are correct, Mr. N is likely to express these issues in the therapeutic relationship in a variety of ways. He might seek out a therapist who he can see as special and superior like himself, who will share in his perfection and understand him perfectly; and/or he may demean and devalue the therapist, who must ultimately disappoint. Mr. N’s tendency to intellectualize will present difficulties, since he may treat therapeutic insights as “theories” to ponder, without the personal relevance and affective charge that leads to change. The fact that he has found meaning in past painful experiences and grown from them, however, along with his many strengths, increases our confidence that he will use therapy effectively.

Comments on the Case Formulation

We leave to readers to judge the merits of the SWAP-200 as an assessment tool, relative to current instruments intended to assess personality disorders. Three points, however, are worth noting. First, with the SWAP-200 approach, diagnosis and case formulation are part of the same process. The SWAP-200 provides both a Q-scores profile for diagnostic purposes (figure 1) and a narrative description useful for case formulation. Moreover, the standard vocabulary of the SWAP-200 ensures that different clinicians will describe the same patient in much the same way once they learn to use the SWAP-200 reliably. Had another clinician described Mr. N using the SWAP-200, the narrative description would have been much the same (since every word was taken directly from the SWAP-200 item set).

Second, the constellation of seemingly contradictory qualities embodied in Mr. N’s narrative description—such as the paradoxical combination of several unpleasant narcissistic qualities and a tendency to elicit liking in others—is normative with the SWAP-200 and, we believe, normative in human personality. A system for classifying and assessing personality for clinical purposes should, we believe, encompass this human complexity, not describe caricatures.

Third, the SWAP-200 can be used not only to classify patients into categories, such as narcissistic personality disorder, but to make fine-grained distinctions among patients within a diagnostic category. For example, we note that Mr. N has a capacity for genuine insight and growth and suspect that his prognosis is far more favorable than that of many other patients with narcissistic personality disorder, particularly those with more antisocial features. With the SWAP-200, this is a testable hypothesis.

Toward DSM-V

Thus far, we have avoided the thorny question of how the findings of this study, if they prove replicable, could be used to revise axis II. Using the actual SWAP-200 procedure would be essential for diagnosis in research contexts and would also make sense in certain clinical situations, such as forensic evaluations, or in cases where the diagnostic picture is unclear. In these cases, a Q-score profile (figure 1) could provide both dimensional and categorical diagnosis (where categorical diagnoses are made when Q-scores exceed a critical cutoff point, such as two standard deviations above the mean).

In daily clinical practice, routine use of the SWAP-200 would be impractical and fortunately is unnecessary. The simplest way to revise axis II, which would preserve much of its familiar format and hence be readily used by clinicians, would be to replace the current approach with a prototype matching procedure that yields both dimensional and categorical diagnoses. The most diagnostic or important items for each Q-factor could serve as criteria sets. To maximize internal consistency and minimize comorbidity, the number of criteria per disorder would need to be greater than the current seven to 10 criteria per disorder. Thus, the prototype for each disorder might include the top 18 SWAP-200 items (this is the number of SWAP-200 items in the two “most descriptive” categories, 6 and 7), or each category could include as many items as necessary to achieve a coefficient alpha >0.80 for the item set (i.e., high internal consistency). Thus, the criteria sets would resemble the listing of items in tables 1 through 7, arranged in descending order of importance.

To make a diagnosis, clinicians could simply rate the extent to which a patient matches each of the seven criteria sets (or 11 criteria sets, if the dysphoric category is divided into five subtypes), using, for example, a 0–7 rating scale (0=the patient has no resemblance to the diagnostic prototype, 3=the patient has features of the disorder, 5=the patient matches the prototype well enough to receive a diagnosis, 7=the patient is a relatively pure and prototypic example of the disorder). If such a rating system were used, Mr. N might receive the following dimensional diagnoses: dysphoric personality disorder, 0; antisocial personality disorder, 1; schizoid personality disorder, 0; paranoid personality disorder, 0; obsessional personality disorder, 3; histrionic personality disorder, 2; and narcissistic personality disorder, 5. The categorical diagnosis would be narcissistic personality disorder with obsessional features.

This rating procedure would likely take no more than a moment or two of a clinician’s time once the clinician became familiar with the diagnostic manual. It would yield diagnoses similar to those currently used by clinicians, such as “paranoid personality disorder with schizoid features.” Whether this approach would render clinical diagnoses more or less reliable is an empirical question, although we doubt it would prove less reliable than current categorical clinical diagnoses.

Limitations

Beyond the potential objections discussed in part I, this study has a number of limitations, of which we believe two are most significant and point the way toward future research. The first is that the research design was biased to increase the chances of duplicating the current axis II taxonomy, since our clinicians described only patients who met current axis II criteria for a personality disorder. We deliberately chose this research strategy so we could 1) evaluate the validity of the new approach relative to familiar axis II categories, and 2) be certain that we included patients who spanned the entire spectrum of current, recently recognized, and “under consideration” personality disorder syndromes. Given this research strategy, it is striking that the Q-factor analysis did not simply replicate the current taxonomy, but instead suggested an alternative taxonomy.

Second, this study relied exclusively on data from only one source, clinicians. Future research should include other data sources (e.g., self-reports from patients, data from informants) to triangulate on the constructs of interest, and to evaluate whether other data sources support the empirically derived taxonomy. We would not expect total concordance between data sources, since we do not believe that patients can self-report about many important personality processes. Nevertheless, some concordance seems likely, and comparable findings across assessment methods would increase our confidence in the obtained findings.

The problems inherent in relying on a single data source (in this case, clinicians) are by no means unique to this study, since most published studies of personality and personality disorders rely exclusively on a single data source, usually an interviewer’s judgment after a brief clinical interview, or self-report data, both of which ultimately rely on patients’ answers to direct questions. We believe the quantified clinical data reported here, obtained from clinicians who have worked with patients longitudinally, are at least as sound as data obtained through the more usual methods.

Received Jan. 14, 1998; revision received June 22, 1998; accepted Aug. 25, 1998. From the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston; and The Cambridge Hospital/Cambridge Health Alliance. Address reprint requests to Dr. Westen, Department of Psychiatry, The Cambridge Hospital, 1493 Cambridge St., Cambridge, MA 02139; [email protected] (e-mail). The authors acknowledge the assistance of the over 950 clinicians who helped to refine the SWAP-200 assessment instrument, including the 797 who participated in the present study. They also thank several research assistants who helped in the collection of the data, particularly Michelle Levine, Alan Reyes, Lisa Goldstein, and Elizabeth Schafer.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FIGURE 1. A Diagnostic Profile for Mr. N

1. Widiger T, Frances A: Towards a dimensional model for the personality disorders, in Personality Disorders and the Five-Factor Model of Personality. Edited by Costa P, Widiger T. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1994, pp 19–39Google Scholar

2. Livesley WJ (ed): The DSM-IV Personality Disorders. New York, Guilford Press, 1995Google Scholar

3. Morey LC: Personality disorders in DSM-III and DSM-III-R: convergence, coverage, and internal consistency. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:573–577Link, Google Scholar

4. Bell E, Jackson D: The structure of personality disorders in DSM-III. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992; 85:279–287Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Mischel W, Shoda Y: A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychol Rev 1995; 102:246–268Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Westen D: A clinical-empirical model of personality: life after the Mischelian ice age and the NEO-lithic era. J Personality 1995; 63:495–524Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Westen D: Case formulation and personality diagnosis: two processes or one? in Making Diagnosis Meaningful. Edited by Barron J. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association Press, 1998, pp 111–138Google Scholar

8. Bernstein DP, Useda D, Siever L: Paranoid personality disorder, in The DSM-IV Personality Disorders. Edited by Livesley WJ. New York, Guilford Press, 1995, pp 45–57Google Scholar

9. Hare R, Hart S: Commentary on antisocial personality disorder: the DSM-IV field trial. Ibid, pp 127–134Google Scholar

10. Block J: Lives Through Time. Berkeley, Calif, Bancroft, 1971Google Scholar

11. Block J: The Q-Sort Method in Personality Assessment and Psychiatric Research. Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1978Google Scholar

12. Block J, Gjerde P, Block J: Personality antecedents of depressive tendencies in 18-year-olds: a prospective study. J Pers Soc Psychol 1991; 60:726–738Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Colvin R, Block J, Funder D: Overly positive self evaluations and personality: negative implications for mental health. J Pers Soc Psychol 1995; 68:1152–1162Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. John O, Robins RW: Accuracy and bias in self-perception: individual differences in self-enhancement and the role of narcissism. J Pers Social Psychol 1994; 66:206–219Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Shedler J, Block J: Adolescent drug use and psychological health: a longitudinal inquiry. Am Psychol 1990; 45:612–630Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Westen D, Muderrisoglu S, Fowler C, Shedler J, Koren D: Affect regulation and affective experience: individual differences, group differences, and measurement using a Q-sort procedure. J Consult Clin Psychol 1997; 65:429–439Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Shedler J, Westen D: Refining the measurement of axis II: a Q-sort procedure for assessing personality pathology. Assessment 1998; 5:335–355Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Shapiro D: Neurotic Styles. New York, Basic Books, 1965Google Scholar

19. Phillips K, Hirschfeld RMA, Shea MT, Gunderson JG: Depressive personality disorder, in The DSM-IV Personality Disorders. Edited by Livesley WJ. New York, Guilford Press, 1995, pp 287–302Google Scholar

20. Livesley WJ: Preface. Ibid, pp v–xGoogle Scholar

21. Westen D: Divergences between clinical and research methods for assessing personality disorders: implications for research and the evolution of axis II. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:895–903Link, Google Scholar

22. Westen D, Arkowitz-Westen L: Limitations of axis II in diagnosing personality pathology in clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1767–1771Link, Google Scholar

23. Meehl P: Bootstraps taxometrics: Solving the classification problem in psychopathology. Am Psychol 1995; 50:266–275Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Vaillant G (ed): Ego Mechanisms of Defense: A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1992Google Scholar

25. Jones E, Windholz M: The psychoanalytic case study: toward a method for systematic inquiry. J Am Psychoanal Assoc 1990; 38:985–1012Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar