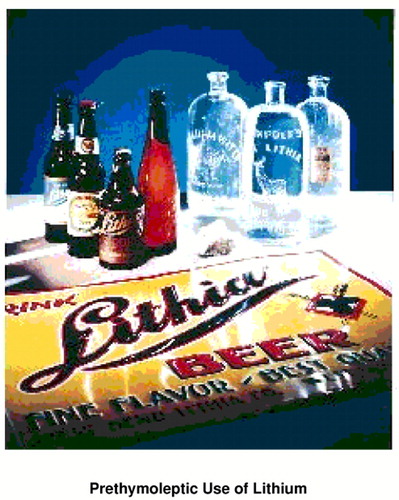

Prethymoleptic Use of Lithium

Before its introduction into modern psychiatry, lithium was a widely consumed substance. Medicinal interest in lithium began in the mid-1800s when A. Lipowitz and Alexander Ure described the ability of lithium solutions to dissolve uric acid crystals in vitro. This led to the belief that lithium was useful in the treatment of gout. The British physician Sir A.B. Garrod was a strong proponent of its use to treat gout. He established dosing guidelines and described the now well-established side effects of tremor, polyuria, and gastrointestinal disturbance (1). It was Alexander Haig’s writings on the “uric acid diathesis,” however, that led to the widespread use of lithium. Haig believed that a great variety of ills, including angina, asthma, arthritis, depression, headaches, hypertension, and epilepsy, were caused by imbalances of uric acid (1). Consequently, he advocated lithium for many patients suffering from these symptoms (2).

Quickly, claims of the pan-potency of lithium mushroomed. In 1871, William A. Hammond, M.D., former U.S. Surgeon General, described the use of lithium bromide as a treatment for mania. Shortly thereafter (in 1876), Garrod expressed his belief that mood disorders were caused by “gout retroceding to the head” (2, p. 9). In a 1910 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, an advertisement by a pharmaceutical manufacturer, Charles L. Mitchell, M.D., claimed that his “laxative alkaline salt of lithia” was indicated for “gout, rheumatism, uric acid diathesis, constipation acute and chronic, hepatic torpor, obesity, Bright’s disease, albuminuria of pregnancy, asthma, incontinence of urine, gravel, cystitis, urinogenital disorders, headache, neuralgia and lumbago.... It is also an excellent antimalarial, relieving hepatic torpor and congestion, and increasing twofold the action of quinine” (1, p 462). These claims fueled the market for lithiated products—usually waters containing lithium, but also a beer, Lithia Beer, brewed for years at West Bend, Wis., with water from a lithia spring. Buffalo Lithia Springs Water, a widely consumed product at the turn of the century, was advertised as “a valuable adjunct to the physician in the treatment of fevers, malaria, typho-malaria, and atypical typhoid” (1, p. 462). Manadnock Lithia Spring Water was recommended for “gout, dyspepsia, rheumatism, eczema, sugar diabetes, Bright’s disease, gall stones; also reduces temperature in all fevers; and all diseases of the kidneys, asthma, etc.” (3, p 73). The lithia water bubble burst eventually, in part because the lithium content of these waters was negligible. For example, it was estimated that at least 150,000 gallons per day of Buffalo Lithia Water would have to be consumed to obtain a therapeutic dose of lithium (3).

By the 1940s, medical interest in lithium had turned to its use as a table salt substitute (in the form of lithium chloride) for cardiac patients. However, the ingestion of uncontrolled amounts of lithium by medically compromised individuals on low-sodium diets, who frequently had impaired renal function and were often taking diuretics, led to several deaths due to lithium toxicity (1–3). This accelerated the already waning interest in the general consumption of lithium and created a barrier to the widespread acceptance of the psychiatric uses of lithium that persisted for some 20 years after Cade’s original report (4), which, coincidentally, was published in 1949, the same year that the lithium chloride salt substitute toxicities were described.

Dr. El-Mallakh, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, KY 40292. Photograph from the collection of Dr. Jefferson.

1. El-Mallakh RS: Prethymoleptic uses of lithium in the United States. Louisville Med 1996; 56:461–463Google Scholar

2. Johnson FN: The History of Lithium Therapy. London, MacMillan, 1984Google Scholar

3. Strobusch AD, Jefferson JW: The checkered history of lithium in medicine. Pharmacy in History 1980; 22:72–76Medline, Google Scholar

4. Cade JFJ: Lithium salts in the treatment of psychotic excitement. Med J Aust 1949; 36:349–352Google Scholar