Vulnerability to Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Adult Offspring of Holocaust Survivors

Abstract

Objective: There has been considerable controversy regarding the impact of the Holocaust on the second generation, but few empirical data are available that systematically document trauma exposure and psychiatric disorder in these individuals. To obtain such data, the authors examined the prevalence of stress and exposure to trauma, current and lifetime posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and other psychiatric diagnoses in a group of adult offspring of Holocaust survivors (N=100) and a demographically similar comparison group (N=44).Method: Subjects were recruited from both community and clinical populations and were evaluated with the use of structured clinical instruments. Stress and trauma history were evaluated with the Antonovsky Life Crises Scale and the Trauma History Questionnaire, PTSD was diagnosed with the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale, and other psychiatric disorders were evaluated according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Results: The data show that although adult offspring of Holocaust survivors did not experience more traumatic events, they had a greater prevalence of current and lifetime PTSD and other psychiatric diagnoses than the demographically similar comparison subjects. This was true in both community and clinical subjects.Conclusions: The findings demonstrate an increased vulnerability to PTSD and other psychiatric disorders among offspring of Holocaust survivors, thus identifying adult offspring as a possible high-risk group within which to explore the individual differences that constitute risk factors for PTSD. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155: 1163-1171

With few exceptions, the literature on adult offspring of Holocaust survivors is divided into two camps: descriptions of the adverse effects of the Holocaust on the second generation and failures to find such effects. Initial reports described an unusually high incidence of depression, anxiety, conduct disorder, personality problems, inadequate maturity, excessive dependence, and poor coping in the children of Holocaust survivors (1-5). In addition, offspring of Holocaust survivors were described as having a general fragility and vulnerability to stress (68). Barocas and Barocas (6) commented not only on the alarming number of children of survivors seeking and requiring help but also on the striking resemblance between symptoms of the children and those of the parents. They described offspring of Holocaust survivors as “showing symptoms that would be expected if they actually lived through the Holocaust.” Rosenheck and Nathan (9), in their study of children of Vietnam combat veterans, also observed that children of trauma survivors display symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Implicit in the literature mentioned above is the attribution of psychiatric problems in the children of trauma survivors to the parental trauma. However, the literature has been ambiguous about whether symptoms in offspring are due to the indirect exposure to traumatic material as described by the parents (which could fit DSM-IV criterion A[1]: being confronted with information about threats to the parents’ lives) or, rather, the direct effect of parental inability to provide appropriate nurturing (which would not necessarily constitute a DSM-IV-defined traumatic experience). The descriptions of a generalized vulnerability (6, 7) suggest a third etiologic model: offspring of trauma survivors are relatively more likely to develop PTSD in response to their own traumatic life events. Indeed, in the only study of offspring of Holocaust survivors in which a traumatic life event other than the Holocaust was considered, Solomon et al. (10) found that offspring of Holocaust survivors were more likely to develop PTSD after deployment in the Lebanon war than Israeli soldiers whose parents were not Holocaust survivors. These investigators suggested that the increased incidence of PTSD after the Lebanon war in the offspring of Holocaust survivors reflected “responses that the children ‘learned’ from their survivor parents. For example, the second generation PTSD casualty may have more war-related nightmares than his control group peers because he had seen and heard his parents venting their emotion” (10).

The interpretation by Solomon et al. of their results assumes that offspring “learned” responses that were not learned by control subjects. However, since an important risk factor for the development of PTSD is an individual’s own prior history of trauma (11, 12), it may be that the higher rate of PTSD in offspring reflected more stressful or traumatic life events other than the effects of parental trauma. In the absence of knowledge about each individual’s stress history, it is difficult to attribute PTSD to hypothetical learned responses.

To attribute PTSD or other psychopathology in offspring of trauma survivors to the effect of parental trauma, other competing explanations must be excluded. Specifically, it is necessary to evaluate systematically the potential differences in stressful or traumatic life events other than those related to the parental trauma. This is particularly important because so many investigators have not observed differences in psychopathological features characterizing children of survivors (13-16) or in MMPI-derived measures of global mental health (17), anxiety, depression, or adjustment (18) and have thus attributed findings of pathology to methodological bias or other artifacts. Indeed, a common critique of studies of psychopathology in offspring of trauma survivors is that these investigations have primarily used clinical samples who may not be representative of Holocaust offspring in general (16, 19).

Solkoff’s critical review (20) concluded that almost no study of children of Holocaust survivors, including studies of nonclinical samples, met the necessary methodological criteria for subject selection and exclusion of other biases. This indictment renders inconclusive almost all of the literature on the presence or absence of pathology due to parental trauma. Invariably, individuals who agree to participate in any research are a self-selected group who may be quite different from those who choose not to participate; however, the bias depends on the motives of the volunteers. Obtaining a truly representative sample requires knowledge of what proportion of the offspring population seeks treatment. In the absence of knowledge of this proportion, the degree and nature of the bias in any offspring sample cannot be established.

The present study was undertaken to examine stress and trauma exposure, current and lifetime PTSD, and other psychiatric diagnoses in a group of offspring of Holocaust survivors and a demographically similar comparison group. Given the emphasis in the literature on the necessity of selecting a representative study group, we attempted to recruit and interview subjects from many different sources. We also performed several different comparisons in order to detect potential differences resulting from selection biases. In addition to comparing Holocaust and non-Holocaust offspring, we compared Holocaust offspring not recruited from a clinical population with both the comparison subjects and the offspring recruited from a clinical population. Excluding treatment participants from an analysis biases the sample by overrepresenting persons who do not seek treatment, but it excludes the possibility of the opposite bias of overrepresenting non-treatment-seeking offspring in the sample. Direct comparison of offspring from a clinical population with offspring recruited by other methods assesses the extent of bias that has been hypothesized.

METHOD

The subjects were 100 offspring (29 men and 71 women) and 44 comparison subjects (23 men and 21 women). Offspring were defined as having been raised by at least one biological parent who survived the Nazi Holocaust. For the purposes of this study, Holocaust survivors were defined as either having been interned in a Nazi concentration camp or labor camp during World War II or having had to hide in or flee German-occupied territory under threat of death after 1939. All but 11 offspring in the study were raised by two Holocaust survivor parents (seven offspring had only a father who was a survivor, and four had only a mother who was a survivor). The comparison subjects were Jewish, within the same age range (i.e., 28–50 years), and did not have a parent who was a Holocaust survivor. The majority of the comparison subjects had two American-born parents (however, three mothers and five fathers were born in Europe, Canada, or the Middle East).

There were two types of recruitment for the study. The clinical sample consisted of offspring who had participated in short-term group psychotherapy in the Mount Sinai Specialized Treatment Program for Holocaust Survivors and Their Families and who were informed about the research and elected to participate. The nonclinical sample consisted of volunteers solicited from lists obtained from the Jewish community (i.e., an epidemiologic-study-like recruitment that did not identify the offspring status of subjects) or who had responded to newspaper advertisements and community group announcements for research participants. The nonclinical sample included both offspring and comparison subjects. There were no exclusions for current or past psychiatric problems (because we were interested in measuring rates of psychiatric disorders) or for any reasons other than age and non-Jewishness. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Subjects provided written informed consent prior to their participation.

Past and current life stress and trauma were assessed with the use of two different scales. The Trauma History Questionnaire (B. Green, unpublished instrument, available from the first author) is a list of 23 potentially traumatic (mostly potentially life-threatening) events, including crime, disaster, and physical and sexual assaults; it also contains an open-ended question for specifying other extraordinarily stressful situations or events. Subjects were asked the number of times they experienced each of these events and at what ages. The events were then further classified as low-magnitude events (e.g., mugging without a weapon, motor vehicle accident without injury, sexual touching) and high-magnitude events (e.g., mugging with a weapon, motor vehicle accident with injury, rape). The Antonovsky Life Crises Scale (21) was used to inquire about cumulative stressful life events. This scale lists both life-threatening events (e.g., having a life-threatening illness, having wartime experiences) and non-life-threatening events (e.g., family in extreme financial debt, denial of a promotion at work, feeling overwhelmed by too many responsibilities). The scale also includes several open-ended questions for specifying events that “caused great suffering or tension” and is therefore sensitive to many typical stressful life experiences in addition to the extraordinary events that are classically associated with the subsequent development of PTSD.

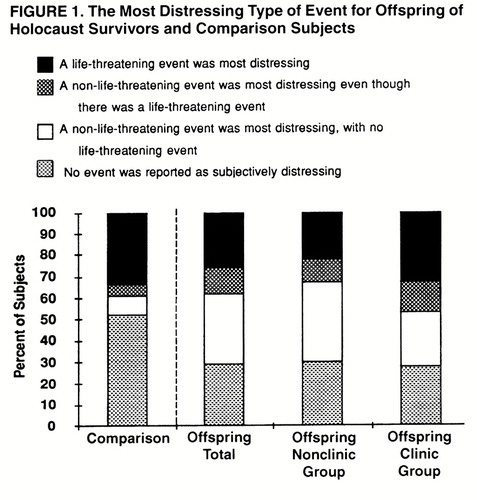

After both scales had been completed, subjects were asked to rank, in order of severity, events meeting the DSM-IV criteria for PTSD (specified as events “that involved a threat to the physical integrity of self or others” [life-threatening] to which they had responded with “intense fear, helplessness, or horror”). After ranking these events, they were asked to indicate the most distressing event (i.e., an event that involved a response of “intense fear, helplessness, or horror”) even if that event had not been life-threatening. This question allowed us to assess PTSD symptoms in response to events that would likely meet the DSM-III-R (but not the DSM-IV) criteria, that is, events “outside the range of usual human experience that would be markedly distressing to almost anyone.” Four groups were generated from the responses to these questions: 1) those for whom a life-threatening event was the most distressing; 2) those for whom a non-life-threatening event was the most distressing, although there was a life-threatening event; 3) those for whom a non-life-threatening event was the most distressing, with no life-threatening event; and 4) those who considered no event distressing enough to cause fear, helplessness, and horror at the time that it occurred.

For the first three categories, PTSD symptoms were assessed with regard to the most distressing event with use of the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (22) and the DSM-IV symptom criteria. If no event was present, the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale was not used, and individual items were automatically scored as 0. Psychiatric diagnoses other than PTSD were made according to DSM-IV criteria adapted from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (23). The full diagnostic interview was used only for subjects who endorsed a positive response on one or more of the mental health screening questions listed at the beginning of this interview. The diagnostic interviews were conducted by experienced clinicians and raters (K.B.-B., M.W., T.D.) trained by the principal investigator (R.Y.), who was also one of the interviewers.

We were interested in whether offspring and comparison subjects differed in the number and type of stressful or traumatic life events, what they chose as their most distressing event, the current and lifetime prevalence of PTSD, and the current and lifetime prevalence of other psychiatric disorders. For each question, we controlled for differences in recruitment by performing parallel analyses including and excluding offspring recruited from treatment participants and also differentiating between offspring recruited from treatment participants and from volunteers. For continuous measures we used the results of Student’s t test (with degrees of freedom an integer) or the Smith-Sattersthwaite approximate t test (with degrees of freedom a fraction). For discrete measures we used Pearson’s chi-square analyses of contingency tables. Similar analyses were performed separately for men and women.

RESULTS

The mean age of the offspring of Holocaust survivors was 39.4 years (SD=6.0), and the mean age of the comparison subjects was 36.9 years (SD=8.5); the difference was not statistically significant. Thirty percent of the offspring and 19% of the comparison subjects were born outside the United States (i.e., in Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Germany, France, Romania, Poland, Iran, Israel, South America, and Canada), but all subjects were born at least 1 year after the end of World War II. The two groups did not differ in years of education (offspring: mean=17.8, SD=1.8; comparison subjects: mean=18.9, SD=2.3). The two groups did differ in treatment-seeking behavior: 72% of the offspring and 39% of the comparison subjects had sought mental health treatment in the past (χ2=12.24, df=1, p=0.0005).

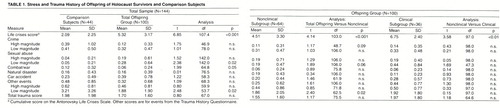

The adult children of Holocaust survivors reported experiencing a greater degree of cumulative lifetime stress than the demographically similar comparison subjects, as measured by the Antonovsky Life Stress Scale. Table 1 presents the results of the comparisons between the offspring and the comparison subjects on measures of stress and trauma exposure. With regard to the number of traumatic (i.e., potentially life-threatening) events, there were some differences on individual items endorsed on the Trauma History Questionnaire. Offspring had more instances of low-magnitude sexual abuse (e.g., molestation), whereas comparison subjects had been exposed to more combat trauma and more low-magnitude events (e.g., burglary, robbery without a weapon, low-severity car accidents, witnessing dead bodies). None of these differences was significant when we controlled for the number of items evaluated by using the Bonferroni inequality correction. Thus, the offspring did not have substantially different trauma exposure from that of the comparison subjects. These results were not substantially affected when the offspring group excluded treatment participants. The clinical and nonclinical subgroups of offspring differed on the Antonovsky Life Crises Scale (the clinical subgroup showing higher scores) but did not differ significantly on any of the other variables.

Figure 1 displays the types of events that subjects rated as most distressing (i.e., an event that involved a response of intense fear, helplessness, or horror even if that event had not been life-threatening). Offspring and comparison subjects had very different rates in the four categories (χ2=13.82, df=3, p=0.003). This difference reflected the fact that offspring were more likely than comparison subjects to endorse a non-life-threatening event as the most distressing (group 2 or group 3). Among the comparison subjects who had experienced a potentially life-threatening event (groups 1 and 2), only 13% characterized some other event as most distressing (group 2). In contrast, 32% of the offspring who had experienced a potentially life-threatening event characterized some other event as most distressing. Furthermore, among the comparison subjects who had not experienced a potentially life-threatening event (groups 3 and 4), only 17% indicated a distressing event (group 3). In contrast, 52% of the offspring who had not experienced a potentially life-threatening event indicated a distressing event. However, there was little difference in the 34% of offspring and 40% of comparison subjects who had experienced at least one high-magnitude event that would qualify as potentially life-threatening (groups 1 and 2). When clinical offspring were excluded from the analysis, these patterns were even stronger (χ2=14.26, df=3, p=0.003). However, there was no significant difference between offspring in the nonclinical subgroup and those in the clinical subgroup (χ2=2.40, df=3, n.s.).

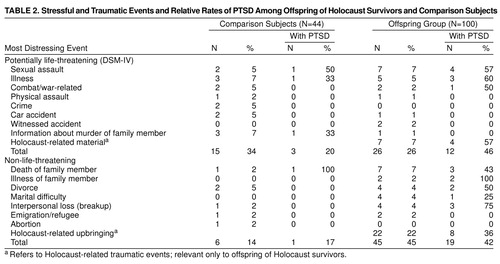

Offspring and comparison subjects endorsed similar life-threatening events, with the exception that offspring were affected by the Holocaust-related stories of their parents, whereas comparison subjects did not report being distressed by experiences of family members (table 2). The non-life-threatening events that offspring endorsed as most distressing were childhood experiences relating to being the offspring of a Holocaust survivor, death or prolonged illness of a parent or sibling, divorce, marital difficulty, or termination of a romantic relationship. With the exception of Holocaust-related upbringing, comparison subjects typically chose similar events, but less frequently (table 2). Thus, for both potentially life-threatening and non-life-threatening events, a substantial proportion of traumatic events for offspring were related to the Holocaust.

Table 2 also displays the percentages of lifetime PTSD among subjects who endorsed particular distressing events. About one-fourth of the offspring and one-third of the comparison subjects endorsed a DSM-IV traumatic event as their most distressing. Under strict DSM-IV criteria, only 34% of the comparison subjects and 26% of the offspring would technically qualify for PTSD according to criterion A. Of those subjects, 20% of the comparison subjects and 46% of the offspring developed PTSD (χ2=2.80, df=1, p<0.10). The percentages of comparison subjects (17%) and offspring (42%) who had PTSD in response to non-life-threatening events were the same as the percentages for PTSD in response to life-threatening events.

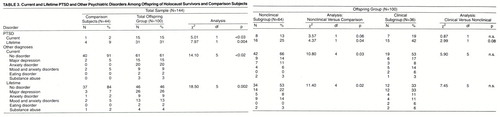

Table 3 presents the rates of current and lifetime PTSD in response to both life-threatening and non-life-threatening events. The prevalence of current PTSD was significantly higher in the children of Holocaust survivors (15%) than the comparison subjects (2%). When treatment-seeking offspring were excluded, the difference in prevalence of current PTSD remained nearly significant. However, the clinical and nonclinical subgroups were not significantly different in the prevalence of current PTSD. The prevalence of lifetime PTSD was also significantly higher among the children of Holocaust survivors (31%) than among the comparison subjects (9%). When the clinical subgroup was excluded, the results were still statistically significant. The difference between the clinical and nonclinical subgroups in the prevalence of lifetime PTSD was not statistically significant but showed a trend.

Since PTSD in offspring included PTSD in response to Holocaust-related events (table 2), which was not the case for the comparison subjects, we compared the prevalence of PTSD in subjects reporting non-Holocaust events as most disturbing (and omitted those with Holocaust-related events in this analysis). Of these 42 offspring, 45% (N=19) developed lifetime PTSD. This rate was significantly higher than the 19% prevalence (N=4) among the 21 comparison subjects (χ2=4.14, df=1, p<0.05).

Table 3 shows the results of the comparison of the groups on other current and lifetime psychiatric diagnoses. Nine percent (N=4) of the comparison subjects met diagnostic criteria for a current disorder, compared with 39% of the offspring. Similarly, 16% (N=7) of the comparison subjects met diagnostic criteria for a lifetime psychiatric disorder, compared with 54% of the offspring. When treatment-seeking offspring were excluded, the prevalence of psychiatric disorders was also reduced but retained statistical significance (p=0.02).

The results for men and women in all of the analyses reported above were not substantially different, but results were consistently less significant because of smaller subgroups.

DISCUSSION

These results provide the first comprehensive and structured clinical assessment of trauma exposure, PTSD, and other psychiatric disorders in a group of adult offspring of Holocaust survivors and demographically matched comparison subjects. The offspring of Holocaust survivors reported more stressful events than the comparison subjects as reflected by the Antonovsky Life Crises Scale. However, they did not experience more potentially traumatic life events as noted in the Trauma History Questionnaire. This study also demonstrated a significantly higher prevalence of both current and lifetime PTSD and other psychiatric disorders in the offspring of Holocaust survivors than in the comparison subjects.

The distinction between scores on the Antonovsky Life Crises Scale and scores on the Trauma History Questionnaire suggests that the offspring of Holocaust survivors either actually experienced more ordinary life stress or were more likely to characterize these experiences as major problems or crises. Similarly, the offspring who were recruited from the clinic reported more stressful life events than those recruited from the community, but there were no differences in their exposure to potentially traumatic life events. It is noteworthy that the only measure in this study that distinguished offspring recruited from the clinic and those from the community was the score on the Antonovsky Life Crises Scale.

Although similar proportions of Holocaust offspring and comparison subjects experienced potentially life-threatening events, the Holocaust offspring were more likely than the comparison subjects to designate a non-life-threatening event as their most distressing event. About one-fourth of the offspring designated Holocaust-related upbringing. It is important to note that this choice of “event” was not included among the questions of either the Antonovsky Life Crises Scale or the Trauma History Questionnaire; it had to be volunteered spontaneously during one of these two structured interviews or as a direct response to the question about the most subjectively distressing event. In all cases, offspring were asked to clarify this response so that the interviewer could identify the nature of the stressor. Typical responses included the physical and emotional damage to the parent, the emotional and/or physical neglect of the child by the parent, the responsibility of caring for the parent from a young age, the minimizing of the offspring’s own life experiences in contrast to the Holocaust, the burden of compensating the parent for past losses, and being taught to fear the environment and react to it with inappropriate hypervigilance and distrust. In all cases, offspring provided vignettes that related parental behavior to the offspring’s symptoms. About one-third (N=8 of 22) of the offspring who reported this as their most distressing event developed PTSD in response to it. The other non-life-threatening events typically involved loss of or separation from a significant other. In particular, offspring reported these types of losses as very upsetting. Such losses were also particularly prevalent in the responses to the Antonovsky Life Crises Scale in comparison with other life stressors such as loss of a job or financial difficulty.

DSM-IV criterion A for a focal traumatic event includes confrontation with information about an event that involved the actual or threatened death or serious injury of someone else. It is unclear whether “confrontation” refers only to current or recent events as opposed to distant life events. Seven percent of all offspring reported that the Holocaust stories of events that occurred to their parents caused them great distress. Typically, the offspring were too young to handle both the graphic information about murder, torture, and rape and the emotional responses of the parents as they relived these experiences. Subsequently, offspring either imagined their parents reexperiencing these events or applied the events to themselves. More than one-half (N=4 of 7) of the offspring who reported this type of trauma as most distressing developed PTSD in response to it.

Even when we considered PTSD only in response to a non-Holocaust-related most-distressing event, the prevalence of PTSD was still significantly higher among Holocaust offspring. This observation is consistent with the report of Solomon et al. (10). When we considered lifetime PTSD only in response to DSM-IV criterion A events, the Holocaust offspring showed a prevalence rate that was twice as high as that of the comparison subjects. This effect was not statistically significant because of the reduced group size (although the results were in the same direction).

This study was initiated just before the publication of DSM-IV. We chose to incorporate the new definition of PTSD with the single modification that the traumatic event need not be life-threatening itself (in accordance with DSM-III-R). We did, however, evaluate PTSD using the stricter criterion A with regard to the subjective response to the event. It is striking that for both the offspring and the comparison subjects, the rate of PTSD was not appreciably different in response to the potentially life-threatening events and to the non-life-threatening events. This result calls for further systematic study of the distinction, if any, between life-threatening (DSM-IV) and non-life-threatening distressing events. In order to understand clinical manifestations of trauma better, it would interesting, for example, to assess biological concomitants of PTSD symptoms in response to each type of event.

In a vulnerability model, the rate of PTSD in response to a focal event would depend on characteristics and experiences of the individual other than those related to the event. Thus, the higher rate of stressors as reflected on the Antonovsky Life Crises Scale may constitute a risk factor for the development of PTSD in response to some other distressing event. Indeed, Resnick et al. (24) found that prior assault was a potent risk factor for the development of PTSD following rape. Similarly, early childhood physical and sexual abuse was associated with a greater prevalence of PTSD following combat (25). When we considered the most distressing non-Holocaust-related events, the greater rate of PTSD in offspring relative to comparison subjects could be attributed to the direct or indirect effect of their offspring status. There are several other indications that offspring were more sensitive to stressors than comparison subjects. When there was no life-threatening event, offspring were more likely than comparison subjects to identify a non-life-threatening event as very distressing. Even when there was a life-threatening event, offspring were more likely than comparison subjects to designate a non-life-threatening event as most distressing, indicating their greater sensitivity to events that many would not regard as worthy of consideration. Corresponding to their greater rates of current and lifetime PTSD, offspring also had higher rates of current and lifetime psychiatric disorders.

It should be noted that our report of increased prevalence of current psychiatric disorders is at variance with the only other study to examine systematically the rates of psychiatric disorders in a nonbiased sample of children of Holocaust survivors and control subjects in Israel (14). That study used a self-report diagnostic assessment and did not evaluate offspring for the presence of PTSD or obtain systematic assessments of exposure to lifetime traumatic stressors. Furthermore, the study did not distinguish between clinical and nonclinical recruitment. Consistent with the observation in the current study, however, was the finding that children of Holocaust survivors had higher rates of past psychiatric disorders.

Although only a few of the comparison subjects met diagnostic criteria for current and lifetime PTSD and other psychiatric disorders, the actual rates of these conditions in the present study group are consistent with base rates in larger, epidemiologic studies. For example, the 9% prevalence of lifetime PTSD in our comparison (normal) group is in line with estimates of Breslau et al. (26) and estimates from both the National Comorbidity Survey (27) and the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study (28). The prevalence of depression and the prevalence of anxiety in the comparison group are also compatible with published population estimates. For example, Wittchen et al. (29) found rates of 4.9% for current depression and 3.5% for anxiety in the population, which are compatible with estimates of 5% for current depression and 5% for anxiety and mood disorders in our comparison subjects. It should be noted, however, that the 5% prevalence rate for substance abuse disorders in both the offspring and comparison groups was considerably lower than reported national estimates of substance abuse (30-32).

In the present study, the primary comparisons were between subjects who were not offspring of Holocaust survivors and a group of offspring of Holocaust survivors that was derived from both clinical and community recruitment. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate systematically the extent to which different types of recruitment might influence variables related to the presence of psychopathology. However, it is clear that there was no substantial clinical distinction between these two offspring subgroups. When differences between offspring recruited only from the community and comparison subjects were evaluated, findings in this offspring subgroup consistently replicated the findings for the entire offspring group, subject to a reduction in power due to the smaller sample size. Thus, the results cannot be attributed to any bias introduced by inclusion of a clinical sample, as has been frequently hypothesized (20).

Despite the aforementioned lack of difference between clinical and community recruitment, it must be emphasized that the nonclinical subjects in this study were not completely randomly ascertained but, rather, were a convenience sample of volunteers who may or may not be representative of the population of Holocaust offspring. Thus, while the present analyses demonstrated no obvious differences between clinical and community subjects, future studies should explore the extent to which volunteer samples in general are representative of the larger population of Holocaust offspring. A further limitation of this study was the moderate size of the study group. This precluded detailed examination of men and women separately and also comparisons of other subgroups of interest that might identify specific risk factors. Nonetheless, the findings are noteworthy in their demonstration of vulnerability to PTSD and other psychiatric disorders in adult offspring of Holocaust survivors.

Because a major question in the field of traumatology is why some individuals develop PTSD while others do not, it is imperative to identify vulnerability factors (33). Since PTSD is relatively rare in the general population, the study of high-risk groups permits more effective identification of vulnerability factors. This study demonstrates that children of trauma survivors may be a prototypic high-risk group within which to explore the individual differences that constitute risk factors. It should be noted that this demonstration of intergenerational PTSD does not indicate the etiology (e.g., heritability, learned responses) or address the biology of the risk of PTSD. However, future studies using such high-risk groups can ultimately shed light on these issues.

Received Sept. 29, 1997; revisions received Jan. 12 and Feb. 27, 1998; accepted April 15, 1998. From the Traumatic Stress Studies Program, Department of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Bronx VA Medical Center.. Address reprint requests to Dr. Yehuda, Department of Psychiatry, 116A, Bronx VA Medical Center, 130 West Kingsbridge Rd., Bronx, NY 10468; [email protected] (e-mail).

|

|

|

1. Rakoff V: A long-term effect of the concentration camp experience. Viewpoints 1966; 1:17–20Google Scholar

2. Rakoff V, Sigal JJ, Epstein N: Children and families of concentration camp survivors. Canada’s Mental Health 1976; 14:24–26Google Scholar

3. Trossman B: Adolescent children of concentration camp survivors. Can Psychiatr Assoc J 1968; 13:121–123Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Sigal JJ, Weinfeld G: Control of aggression in adult children of survivors of the Nazi persecution. J Abnorm Psychol 1985; 94:556–564Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Rosenman S: Out of the Holocaust: children as scarred souls and tempered redeemers. J Psychohistory 1984; 11:556–567Google Scholar

6. Barocas H, Barocas C: Wounds of the fathers: the next generation of Holocaust victims. Int Rev Psychoanal 1983; 5:331–341Google Scholar

7. Danieli Y: Differing adaptational styles in families of survivors of the Nazi Holocaust: some implications for treatment. Children Today 1981; 10:6–10Medline, Google Scholar

8. Dasberg H: Psychological distress of Holocaust survivors and offspring in Israel, forty years later: a review. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 1987; 24:243–256Medline, Google Scholar

9. Rosenheck R, Nathan P: Secondary traumatization in the children of Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1985; 36:538–539Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Solomon Z, Kotler M, Mikulincer M: Combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder among second-generation Holocaust survivors: preliminary findings. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:865–868Link, Google Scholar

11. Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Best CL, Kramer TL: Vulnerability-stress factors in development of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:424–430Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Bremner JP, Randall P, Vermetten E, Staib L, Bronen RA, Mazure C, Capelli S, McCarthy G, Innis RB, Charney DS: MRI based measurement of hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood physical and sexual abuse: a preliminary report. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 41:23–32Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Aleksandrowicz DR: Children of concentration camp survivors, in The Child in His Family, vol 2: The Impact of Disease and Death. Edited by Anthony EJ, Koupernik C. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1973, pp 385–392Google Scholar

14. Schwartz S, Dohrenwend B, Levav I: Nongenetic familial transmission of psychiatric disorders? evidence from children of Holocaust survivors. J Health Soc Behav 1994; 35:385–402Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Zlotogorsku Z: Offspring of concentration camp survivors: the relationship of perceptions of family cohesion and adaptability of levels of ego functioning. Compr Psychiatry 1983; 24:345–354Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Sigal J, Weinfeld M: Mutual involvement and alienation in families of Holocaust survivors. Psychiatry 1987; 50:280–288Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Last U, Klein H: Impact de l’holocauste: transmission aux enfants de vecu des parents (Impact of the Holocaust: transmission of the parents’ experiences to their children). L’Evolution Psychiatrique 1981; 41:375–388Google Scholar

18. Rose SL, Garske J: Family environment, adjustment, and coping among children of Holocaust survivors: a comparative investigation. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1987; 57:332–344Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Felson I, Erlich S: Identification patterns of offspring of Holocaust survivors with their parents. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1990; 60:506–520Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Solkoff N: Children of survivors of the Nazi Holocaust: a critical review of the literature. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1992; 62:342–358Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Antonovsky A: Health, Stress and Coping. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1979Google Scholar

22. Blake D, Weathers F, Nagy D, Kaloupek G, Klauminzer D, Charney D, Keane T: A clinician rating scale for current and lifetime PTSD. Behavior Therapist 1990; 13:187–188Google Scholar

23. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1987Google Scholar

24. Resnick HS, Yehuda R, Pitman RK, Foy DW: Effects of previous trauma on acute plasma cortisol level following rape. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1675–1677Link, Google Scholar

25. Bremner JD, Southwick SM, Johnson DR, Yehuda R, Charney DS: Childhood abuse in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:235–239Link, Google Scholar

26. Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E: Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:216–222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:1048–1060Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Davidson JRT, Hughes D, Blazer D, George LK: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: an epidemiological study. Psychol Med 1991; 21:1–9Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Wittchen HU, Zhao S, Kessler RC: DSM-III-R generalized anxiety disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:355–364Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Judd LL, Paulus MP, Wells KB, Rapaport MH: Socioeconomic burden of subsyndromal depressive symptoms and major depression in a sample of the general population. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1411–1417Link, Google Scholar

31. Anthony JC, Warner LA, Kessler RC: Comparative epidemiology of dependence on tobacco, alcohol, controlled substances, and inhalants: basic findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 1994; 2:244–268Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Bucholz K: Alcohol abuse and dependence from a psychiatric epidemiologic perspective. Alcohol Health Res World 1992; 16:197–208Google Scholar

33. Yehuda R, McFarlane AC: Conflict between current knowledge about posttraumatic stress disorder and its original conceptual basis. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1705–1713Link, Google Scholar