Neuroendocrine Evidence That Clozapine's Serotonergic Antagonism Is Relevant to Its Efficacy in Treating Hallucinations and Other Positive Schizophrenic Symptoms

Abstract

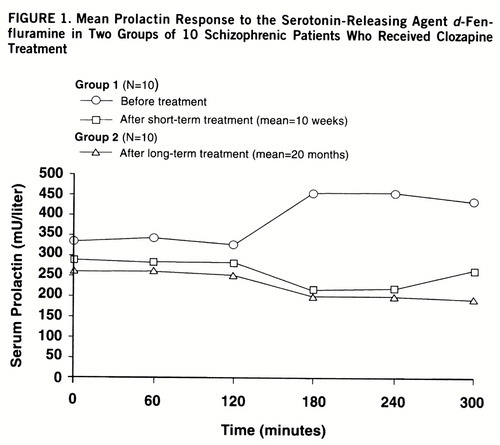

OBJECTIVE: The authors examined the effect of prolonged clozapine treatment on central serotonergic (5-HT) function in schizophrenia. METHOD: Prolactin responses to the 5-HT releasing agent d-fenfluramine were measured in two groups of 10 schizophrenic subjects. The first group was tested twice, before and after a mean of 10 weeks of clozapine treatment. The second group was tested after a mean of 20 months of clozapine treatment. RESULTS: The prolactin response was significantly blunted in these 20 patients treated with clozapine. There was a significant positive correlation between d-fenfluramine-evoked prolactin release and the overall positive symptom score and the hallucination and delusion subscores of the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms. CONCLUSIONS: Blunted 5-HT-mediated prolactin responses in schizophrenic patients receiving clozapine monotherapy for up to 20 months were correlated with reductions in positive symptoms. This suggests that 5-HT antagonism is relevant to clozapine's efficacy in alleviating hallucinations and other positive schizophrenic symptoms.

Compared with conventional neuroleptics, clozapine—an atypical antipsychotic—has superior efficacy (1) and higher affinity at serotonin (5-HT) receptors (2). These data have provoked renewed interest in 5-HT activity in schizophrenia, first suggested by the hallucinatory effects of lysergic acid diethylamine (LSD) (3). Neuroendocrine studies demonstrate that clozapine treatment causes functional alterations in the 5-HT system (4, 5), correlating with global clinical improvement in the short term (6).

The prolactin response to d-fenfluramine is a highly specific test of 5-HT function (7). d-Fenfluramine is a selective 5-HT releasing agent and 5-HT reuptake inhibitor (8), and its neuroendocrine effects in humans are mediated by postsynaptic 5-HT2a and 5-HT2c receptors (9).

We hypothesized that longer-term clozapine treatment would be associated with functional alterations in central 5-HT activity as measured by the prolactin response to d-fenfluramine. We further hypothesized that specific schizophrenic symptoms would be associated with altered central 5-HT activity as measured by d-fenfluramine-evoked prolactin release.

METHOD

Ethics approval of the study was obtained, and all subjects gave written informed consent. The study group comprised two groups of patients with a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia, who met the indications for clozapine therapy. The first group consisted of 10 patients (eight male and two female) with a mean age of 36.3 years (SD=12.9), admitted to the hospital and having all neuroleptic medication stopped at least 2 weeks before an initial neuroendocrine challenge. They were receiving 500 mg/day of clozapine at the time of a second neuroendocrine challenge (mean length of treatment=10.2 weeks). The second group of 10 patients (eight male and two female) had a mean age of 33.4 years (SD=5.1) and had been receiving clozapine for a mean of 20.1 months at a mean daily dose of 330 mg (SD=51); these patients had a single neuroendocrine challenge. Female subjects were tested during the follicular phase of their cycles, and none was using an anovulant contraceptive. Patients were assessed at each neuroendocrine test with the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (10) and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (11) by two investigators (V.A.C. and H.J.).

An indwelling intravenous forearm cannula was inserted at 9:00 a.m. after each patient had fasted overnight. After 30 minutes of rest, the patient received an oral dose of 30 mg of d-fenfluramine. Baseline blood samples were taken at –15 and 0 minutes, and further blood samples were taken at 60, 120, 180, 240, and 300 minutes. Serum was separated and frozen before blind batch analysis. We used the AXSYM system (Abbott Diagnostics, Edinburgh) microparticle enzyme immunoassay and a coefficient of variation of 5% for the range between 506.2 and 620.0 mU/liter for prolactin measurement.

Baseline prolactin values in patients at each neuroendocrine challenge were calculated from the mean of prolactin values at –15 and 0 minutes. At each d-fenfluramine challenge, the change in prolactin level was calculated by subtracting the baseline prolactin value from the maximal prolactin value. Baseline prolactin values and change in prolactin values after long-term clozapine treatment were compared with values from the group tested before and after short-term clozapine treatment by means of independent-sample t tests. Baseline and change in prolactin values before and after short-term clozapine treatment were compared by means of paired-sample t tests.

d-Fenfluramine-evoked prolactin release after long-term treatment was compared over all time points with d-fenfluramine-evoked prolactin release before and after short-term clozapine treatment by a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). The difference in prolactin release before and after short-term clozapine treatment over all time points was compared in each pair of tests by a repeated measures ANOVA.

Mean SAPS and SANS scores after long- and short-term clozapine treatment were compared with scores before treatment in a manner similar to that used in the comparison of baseline and change in prolactin values. Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficient, with a significance level of 0.05, was used to calculate correlations between change in prolactin values and psychiatric symptom ratings.

RESULTS

The baseline mean prolactin value of 265 mU/liter (SD=141) after long-term clozapine treatment did not differ significantly from the mean of 339 mU/liter (SD=165) before clozapine treatment in the first group tested (t=1.1, df=18, p=0.31) or their mean of 289 mU/liter (SD=158) after short-term clozapine treatment (t=0.4, df=18, p=0.70) (figure 1). Baseline mean prolactin values in the patients tested before and after short-term clozapine treatment did not differ significantly (t=1.4, df=9, p=0.20).

d-Fenfluramine-evoked prolactin release was significantly reduced in the patients tested after long-term clozapine treatment (F=4.33, df=5,90, p=0.001) and after short-term clozapine treatment (F=3.07, df=5,45, p<0.02) compared to the patients tested before treatment began. The reductions in d-fenfluramine-evoked prolactin release after short- and long-term treatment were not significantly different (F=0.43, df=5,90, p=0.83).

The mean change in prolactin value of 34 mU/liter (SD=55) after long-term clozapine treatment was significantly less than the mean of 230 mU/liter (SD=165) before clozapine treatment (t=3.4, df=18, p=0.003). The mean change in prolactin value after long-term clozapine treatment did not differ significantly, however, from the mean of 86 mU/liter (SD=108) after short-term treatment (t=1.3, df=18, p=0.21).

Positive and negative symptoms were fewer after short- and long-term clozapine treatment than in patients tested before treatment. The mean SAPS ratings of 22.4 (SD=14.8) after long-term clozapine treatment and 25.7 (SD=18.4) after short-term treatment were significantly lower than the mean rating of 50.9 (SD=32.3) of the patients before treatment (t=2.4, df=18, p<0.03, and t=4.4, df=9, p=0.002, respectively). The mean SANS scores of 32.0 (SD=19.4) after long-term clozapine treatment and 36.0 (SD=7.7) after short-term treatment were significantly lower than the mean score of 49.2 (SD=12.6) of the patients before treatment (t=2.4, df=18, p=0.03, and t=3.6, df=9, p=0.004, respectively).

There was a significant positive correlation between d-fenfluramine-evoked change in prolactin values and the hallucination subscore on the SAPS (r=0.51, N=20, p=0.02), the delusion subscore on the SAPS (r=0.68, N=20, p=0.001), and the overall SAPS score (r=0.50, N=20, p=0.02). There was no significant positive correlation between change in prolactin values and negative symptoms measured by the SANS (r=0.08, N=20, p=0.74).

DISCUSSION

This study, using a highly specific serotonergic neuro~endocrine probe, demonstrated that prolonged clozapine treatment is associated with a blunted prolactin response to d-fenfluramine. The fact that clozapine treatment had no significant effect on baseline prolactin values suggests that this differential prolactin response reflects clozapine's potent affinity at serotonergic receptors, most likely 5-HT2a and 5-HT2c (2). Although the study did not include a placebo challenge in comparison with d-fenfluramine, the consistency of prolactin responses in all 20 patients tested while receiving clozapine and the differences in prolactin release between patients before and after clozapine therapy support the value of d-fenfluramine in assessing the 5-HT activity of clozapine.

To our knowledge, this is the first neuroendocrine study to demonstrate an association between altered d-fenfluramine-evoked prolactin release and specific positive schizophrenic symptoms, namely, hallucinations and delusions. The patients with lower ratings for these symptoms, measured by the SAPS subscores, were more likely to have a blunted prolactin response to d-fenfluramine. We propose that serotonergic antagonism contributes to clozapine's efficacy against positive symptoms, in accordance with recent theories about the pathophysiology of schizophrenic symptoms (12).

There is continued uncertainty about the time course of clinical improvement seen with clozapine treatment; some authors claim that treatment for up to 1 year may be needed to fully assess the likelihood of response (13). This study demonstrates that reductions in 5-HT-mediated neuroendocrine responses persist with longer-term treatment. However, no significant differences in altered 5-HT-mediated neuroendocrine responses were demonstrated between short and prolonged clozapine therapy.

Blunting of d-fenfluramine-evoked prolactin release is unlikely to be an epiphenomenon of clozapine treatment, unrelated to its antipsychotic activity. Its persis~tence after prolonged clozapine therapy and the correlation with specific positive schizophrenic symptoms are evidence for the importance of 5-HT antagonism to clozapine's unique antipsychotic activity.

Received July 7, 1997; revision received Dec. 8, 1997; accepted Dec. 16, 1997. From the Division of Psychiatry, Homerton Hospital, London; the Institute of Psychiatry, London; and the Department of Psychiatry, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. Address reprint requests to Dr. Lucey, Department of Psychiatry, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, James Connolly Memorial Hospital, Dublin 15, Ireland.

FIGURE 1. Mean Prolactin Response to the Serotonin-Releasing Agent d-Fenfluramine in Two Groups of 10 Schizophrenic Patients Who Received Clozapine Treatment

1 Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H: Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic: a double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:789–796Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Nordström A-L, Farde L, Nyberg S, Karlsson P, Halldin C, Sedvall G: D1, D2, and 5-HT2 receptor occupancy in relation to clozapine serum concentration: a PET study of schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1444–1449Link, Google Scholar

3 Wooley DW, Shaw E: A biochemical and pharmacological suggestion about certain mental disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1954; 40:228–231Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Kahn RS, Davidson M, Siever L, Gabriel S, Apter S, Davis KL: Serotonin function and treatment response to clozapine in schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1337–1342Link, Google Scholar

5 Owen RR, Guhewez-Estinou R, Hsiao J, Hadd K, Benkelfat C, Murphy DL, Lawlor BA, Pickar D: Effects of clozapine and fluphenazine treatment on responses to m-chlorophenylpiper~azine infusions in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:636–644Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Curtis VA, Wright P, Reveley A, Kerwin R, Lucey JV: Effect of clozapine on d-fenfluramine evoked neuroendocrine responses in schizophrenia and its relation to clinical improvement. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:642–646Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Invernizzi R, Berettera C, Garattini S, Samanin R: d- and l-isomers of fenfluramine differ markedly in their interaction with brain serotonin and catecholamines in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol 1986; 20:9–15Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Garattini S, Mennini T, Samanin R: From fenfluramine racemate to d-fenfluramine: specificity and potency of the effects on the serotoninergic system and food intake. Ann NY Acad Sci 1987; 499:156–166Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Goodall EM, Cowen PJ, Franklin M, Silverstone T: Ritanserin attenuates anorexic responses to d-fenfluramine in human volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993; 499:156–166Google Scholar

10 Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1983Google Scholar

11 Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1981Google Scholar

12 Breier A: Serotonin, schizophrenia and antipsychotic drug action. Schizophr Res 1995; 14:187–202Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Meltzer HY: Clozapine: is another view valid? (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:821–825Link, Google Scholar