Prevalence of Psychopathology Among Children and Adolescents

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study was done to update and expand information given in recent reviews, provide a more systematic critique of past research, identify current research trends and issues, and explore possible strategies for future research in child psychiatric epidemiology. METHOD: The authors identified and reviewed 52 studies done over the past four decades that attempted to estimate the overall prevalence of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. RESULTS: About as many studies have been published since 1980 as were published before. Sample sizes ranged from 58 to 8,462; most were in the 500–1,000 range. Studies were carried out in over 20 countries, most frequently the United States and the United Kingdom. Subjects' ages ranged from 1 to 18 years. Rutter's criteria were the most frequently used for case definition; more recent studies were more likely to use DSM criteria. The most frequently used interview was the Rutter schedule. The most common time frame for calculating prevalence was the present, followed by 6 months and 1 year. Prevalence estimates of psychopathology ranged from approximately 1% to nearly 51% (mean=15.8%). Median rates were 8% for preschoolers, 12% for preadolescents, 15% for adolescents, and 18% in studies including wider age ranges. CONCLUSIONS: The evidence is less informative than expected because of several problems that continue to plague research on child and adolescent disorders. These involve sampling, case ascertainment, case definition, and data analyses and presentation. Progress in understanding the epidemiology of child disorders will largely depend on whether future research successfully meets these challenges.

Understanding the prevalence of psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents is an essential component of a sound public policy for the provision of mental health and other services. Given the current rapid and extensive changes in social policy and service delivery, such as welfare reform and adoption of managed care, it is timely to review published information about the prevalence of psychopathology among children and youths. A review of published studies can help shape the direction of current and future research and provide the baseline context for interpreting new information as additional data become available.

Our goal was to provide a synthesis of epidemiologic studies that have tried to estimate the prevalence of childhood disorders. To do so, we pursued a strategy that was inclusive temporally and geographically, that focused on clinically meaningful definitions of disorders, and that interpreted the body of empirical data in terms of extant criteria for conducting epidemiologic research on childhood disorders. We limited studies to those that attempted to estimate the prevalence of overall psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Although Rutter (1) identified the research carried out in the early 1950s by Lapouse and Monk (2) as the first large-scale epidemiologic study in child psychiatry, others (3, 4) have pointed out that community surveys of child mental health problems were conducted at least a quarter-century earlier. Links (4) cited Long's (5) as the earliest community survey of child mental health, while Gould et al. (3) cited Wickman's (6) as the earliest school-based survey of child maladjustment. Regardless of how one defines the origins of such research, it is clear that descriptive epidemiologic research on children has a relatively long history (3, 4). The number of epidemiologic studies has steadily increased, with a concomitant need for periodic analysis and synthesis to assess progress in our understanding of the epidemiology of child and adolescent disorders.

Since the early 1980s, several literature reviews have been published which assessed studies that investigated clinical psychiatric disorders and that used systematic strategies to minimize the impact of sampling and nonsampling errors in epidemiologic studies. The strategies addressing the latter have involved the use of standardized diagnostic criteria (e.g., DSM-III) to reduce criterion variance and the use of structured diagnostic interview schedules (e.g., the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children [7]) to reduce information variance. For example, Costello (8) reviewed five studies and Brandenburg et al. (9) reviewed eight studies published in the 1980s (10). Not surprisingly, there was considerable overlap, albeit not complete, between the two sets of studies reviewed. Although these more recent research efforts reflected considerable diversity in geographic location and research methods, they also reflected increasing sophistication in diagnostic procedures and study design. These studies, relying more on structured clinical assessments and explicit diagnostic criteria, have generated more homogeneous results than earlier efforts. This newer generation of studies, in addition to providing estimates of the prevalence of clinical disorder, have confirmed the finding from earlier studies that disorders of childhood and adolescence are relatively common.

RESULTS OF STUDIES REVIEWED

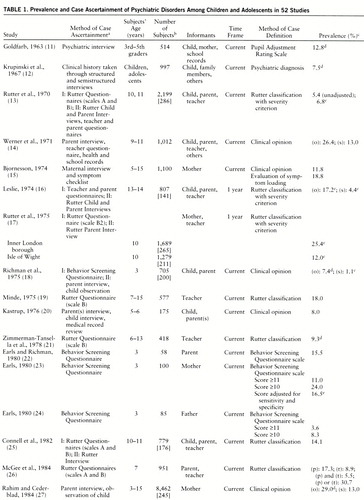

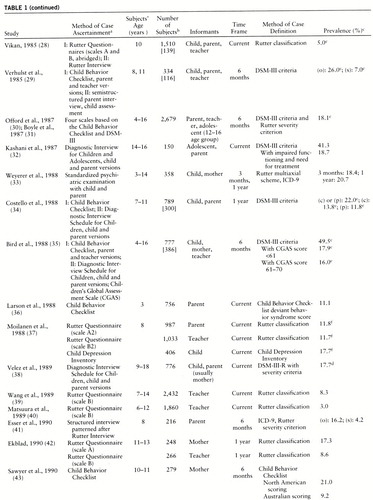

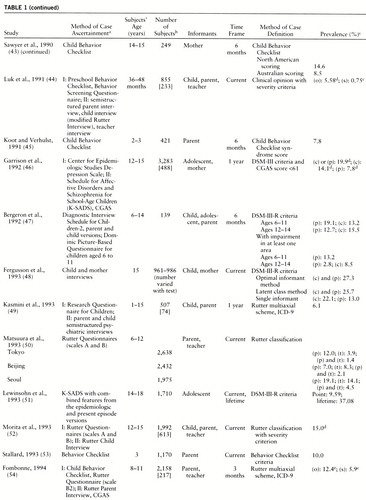

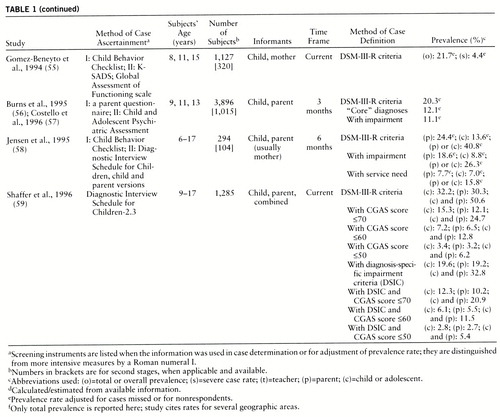

We identified 52 separate studies, reported in 47 sources, that were designed to estimate the overall prevalence of psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents. The studies are summarized in table 1. They were conducted over a period of nearly 40 years, beginning in the 1950s. The samples came from over 20 countries; the United Kingdom and the United States were the most frequent sites, with six and 13 studies, respectively. However, studies were carried out in sites in Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America. Sample sizes ranged from 58 to 8,462 (mean=1,201, median=831). Thirty-three of the 52 studies used single-stage designs, in which all study subjects received some type of psychiatric assessment; sample sizes ranged from 58 to 2,679 (mean=898, median=756). Nineteen studies had two-stage designs, with sample sizes ranging from 294 to 8,462 (mean=1,769, median=1,127) in the first stage and 74 to 1,015 (mean=291, median=233) in the second stage. Mean prevalences were 15.0% in single-stage studies and 17.5% in two-stage studies. Overall, the mean prevalence was 15.8% (median=13.7%, mode=12.0%).

Prevalence rates varied from approximately 1% to almost 51%. The ages of the subjects varied substantially across studies. Accordingly, we grouped samples into four broad categories: preschoolers (ages 1 to 5 or 6 years), preadolescents (ages 6 to 12 or 13 years), adolescents (ages 12 or 13 years and older), and samples including wider age ranges. The 10 preschool samples had a mean prevalence of 10.2% (median=8.3%, range=3.6%–24%). The 21 preadolescent samples had a mean prevalence of 13.2% (median=12.2%, range=1.4%–30.7%), and the 12 adolescent samples had a mean prevalence of 16.5% (median=15.0%, range=6.2%–41.3%). The 14 samples that included multiple age groups had a mean prevalence of 21.9% (median=18.4%, range=7.4%–50.6%).

These rates were generated by diverse methods of data collection (case ascertainment) and equally diverse methods of diagnosis (case definition). By far the most popular case ascertainment procedure was some variation of the Rutter interview schedules or questionnaires (13) (19 studies). In addition, 12 other studies utilized an unspecified psychiatric interview for case ascertainment. Similarly, Rutter's classification procedure was the one most frequently used for case definition (17 studies). DSM-III and DSM-III-R were also used frequently (15 studies), particularly in the more recent studies.

Did the methods of case ascertainment and case definition make a difference? The answer is yes. There was considerable variation in prevalence across all methods. For example, Rutter procedures yielded prevalence rates clustering around 12%. The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS) yielded rates in the 14% range, and the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children yielded prevalence rates in the 20%–25% range. With respect to case definition, DSM-III and DSM-III-R criteria generated similar prevalence rates of 19%–23% and 20%–22%, respectively, while clinical opinion yielded rates of 10%–14%. However, the various procedures yielded prevalence rates that varied by 10%–15% or more across studies, with substantial overlap in ranges across the various procedures. Thus, it is possible to find studies that used a particular method of case ascertainment and case definition which found both higher and lower prevalences of psychiatric disorder than a study that used other procedures.

One of the perennial questions in mental health is whether prevalence rates of psychopathology are changing over time—in particular, whether they are increasing. To examine this question, we grouped studies into those conducted in 1970 or earlier, in 1971–1980, in 1981–1990, and after 1990. The mean prevalence in studies undertaken in 1970 or earlier was 15.4%. The mean prevalence was 14.1% in studies in 1971–1980 and 13.8% in studies spanning 1981–1990. For studies carried out after 1990, the mean prevalence for youths meeting symptom criteria was 26% (range=12.1%–50.6% for child, parent, and combined reports). However, three studies (48, 56, 59) constitute special cases: unlike most previous studies, they used both the child and a parent as the informants, and two of them (48, 59) reported prevalences based on both separate and combined information from the informants. Two of these three studies (56, 59) also reported prevalence rates adjusted for severity or impairment. Therefore, the studies conducted after 1990 are difficult to compare with earlier studies. Excluding these three studies, there appears to be no trend for increasing prevalence among studies carried out since the early 1950s.

There is growing consensus concerning the use of impairment criteria in determining “caseness” (58), and we examined that as well. Twenty-three studies either presented only prevalence rates adjusted for impairment or presented prevalence rates for subjects who met symptom criteria and those who met symptom criteria and had some degree of functional impairment. The prevalence rates adjusted for impairment were typically less (sometimes much less) than one-half the prevalence rates based only on meeting symptom criteria. However, from the data of the 23 studies that did adjust for impairment, it is very clear that there is little consensus on how to assess the degree of impairment in children or adolescents who meet or exceed diagnostic criteria. A variety of impairment measures were used. The two most frequently used were need for treatment and impairment scores derived from some scale, typically the Children's Global Assessment Scale. Upon review of these studies, it is clear that incorporating impairment into diagnostic algorithms substantially affects prevalence rates. What is not clear is what the resulting prevalences mean, as illustrated by two recent articles by Jensen and his colleagues (58) and Shaffer and his colleagues (59).

In the Jensen et al. study, the prevalence of any disorder based on the child interview was 13.6%. This rate dropped to 8.8% if there was impairment in at least one life domain (home, school, peers) and to 7.0% if there was any indication of need for mental health treatment. In the Shaffer et al. study, the prevalence of criterion symptoms based on child interview was 32.2%, and the prevalence for symptom criteria with impairment in one or more life domains was 19.6%. When Children's Global Assessment Scale scores also were incorporated, the rates dropped even more dramatically—to 2.8% for the child meeting symptom criteria with impairment in at least one of the three life domains and a Children's Global Assessment Scale score of 50 or less. Shaffer and colleagues selected as their “true” prevalence rate one that combined 1) meeting symptom criteria, 2) having impairment in one or more life domains, and 3) having a Children's Global Assessment Scale score of 70 or less. This rate was 10.2% for the parent version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, 12.3% for child version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, and 20.9% for combined interviews. While this procedure appears reasonable, there are no data indicating its criterion or predictive validity.

CENTRAL RESEARCH CHALLENGES

As is apparent from the studies summarized in table 1, the body of evidence from descriptive epidemiologic studies is less informative than might otherwise be the case because of several problems that continue to plague research on child and adolescent disorders. These problems, which we designated as central research challenges, involve sampling, case ascertainment, case definition, and data analyses and presentation (60, 61). Progress in our understanding of the epidemiology of child psychiatric disorders will depend in large part on whether future research successfully meets these challenges. We now examine each of these.

Sampling

Two key problems in sampling relate to represen~tativeness and sample size. Representativeness has been problematic from two perspectives: 1) only a portion of the studies to date have actually used probability sampling designs, and 2) the samples studied do not represent, even when taken as a group, the diversity of the child and adolescent population generally. Most studies have focused on either a narrow age range (middle school, high school) or a specific age (age 3, age 8, age 11, etc.), so we cannot determine how prevalence changes or does not change over the lifespan of childhood. This is a critical issue, since we are unable to ascertain whether there are developmental thresholds for risk of disorder that might be indicated by changes in prevalence by age (62). The larger issue, of course, is the external validity of our results (63).

Sample size was almost without exception small (the median size was 831). This means that the actual number of cases of clinical disorder identified was also quite small in many studies. For example, a prevalence rate of 12% would yield only 120 cases in a sample of 1,000. In the second stage of two-stage studies, the average sample size was only 291, which would yield only 35 cases of clinical disorder at a prevalence of 12%. The most obvious disadvantage of small sample sizes is decreased precision in estimates of prevalence and in estimates of the relative contributions (associations) of putative risk factors.

Case Ascertainment

At this juncture, there are basically two types of standardized interviews for research purposes: structured (such as the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children) and semistructured (such as the K-SADS [57, 64]). From an epidemiologic perspective, Edelbrock and Costello (65) made a provocative observation about the impact of the two types of interviews. They argued that the semistructured interviews require more clinical inference (and expertise), focus on specificity, and use higher diagnostic thresholds; hence, fewer children meet criteria. Structured interviews focus on sensitivity and use lower diagnostic thresholds; hence, more children should meet criteria. What this distinction means for estimates of prevalence is that when the latter interviews are used, prevalences should be higher, and with use of the former, prevalences should be lower, all other things being equal. The three studies based on the K-SADS had prevalences around 14%, whereas those that used the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children had prevalences clustering around 21%–25%. Given the lack of studies using both strategies, the epidemiologic implications of these two alternate strategies remain an empirical question.

A number of writers have argued that estimates of prevalence can be obtained with greater accuracy and less cost by using a multistage design (66, 67). The field appears to be moving in this direction, as two-stage procedures are being used increasingly in epidemiologic studies (for example, reference 9). We found that 19 of the 52 studies used a two-stage design. However, as noted above, the average sample size in the second stage was only about 300. Beyond the issue of sample size, the viability of multistage strategies depends in large part on the efficiency of the first-stage assessment, or the screener (1, 68, 69). Thus far, the efficiency of most screeners for childhood psychopathology leaves much to be desired (70).

Most interview schedules, whether structured or semi~structured, are designed to collect data on child psychopathology from both the parent and the child (65, 71). We found that 26 of the 52 studies collected data from the child and at least one other informant (usually, a parent or teacher). A major issue is that there are no agreed-upon decision rules on how best to use information from multiple informants to make diagnoses in order to estimate prevalence in epidemiologic studies. The problem is that no two studies use the same decision rules in deriving estimates of the prevalence of caseness.

This lack of comparability of prevalence rates across studies led Costello (60) to argue for the importance of reporting diagnostic rates separately by informant. The rationale for such a strategy is twofold. First, the derivation of the prevalence is more readily apparent, more directly interpretable, and, at least theoretically, more reproducible. Second, given the low concordance among different informants (65, 71, 72), it provides separate estimates based on the sources of the diagnostic data; this could be extremely important from an epidemiologic perspective. The critical epidemiologic question is whether different sources yield different prevalences, different natural histories (incidence, duration), and different risk factor profiles. The available data, albeit meager, suggest that prevalences do differ by source (58, 59). In this group of studies, those with a child informant and one other informant reported a prevalence of 20%; in those with a parent informant only, the prevalence was 14%; with a teacher informant only, 9%; and with a child informant only, 15%. Whether natural history or associated risk factors also differ, and in what ways, is essentially unknown.

Case Definition

With the exception of a few studies that used Rutter criteria (17, 25, 28, 73), the overwhelming majority of recent studies have used DSM criteria to define caseness. This accounts, in part, for the narrower range of prevalence rates reported. But definition of a case involves more than just application of diagnostic criteria to ascertain the presence of a psychiatric disorder. It also involves the severity of the disorder, in terms of either functional impairment or perceived need for mental health services (9). The concern about severity emanates in part from concern about whether community or epidemiologic “cases” are cases in the same sense as the cases of children brought to clinical settings (58–60). Part of this concern no doubt stems from the fact that only a small minority of children and adolescents diagnosed in community surveys have had any contact with mental health professionals (74–76).

There is growing concern (58, 59, 77) about the validity of a diagnostic nomenclature that identifies one-fourth to one-third or more children and adolescents as meeting criteria for one or more clinical psychiatric disorders. The degree of inclusiveness is not only counterintuitive but calls into serious question the usefulness of DSM nomenclature in its present form. Future research should focus more on assessing severity of symptoms as well as functional impairment and need for treatment. The available data (58, 59, 78, 79) indicate that a substantial proportion of individuals who meet symptom criteria for a DSM diagnosis appear to be functioning adequately in their lives. This suggests that caseness is best determined by the presence of both symptoms and impairment. If a common strategy could be adopted, it would constitute an important step. In this regard, research comparing treated and community samples in terms of phenomenology, severity, and need for treatment would help resolve the question of comparability of clinical and community cases.

Assessment of severity in the studies reviewed varied substantially. Only 16 of the 52 studies reported prevalence rates adjusted for severity as well as crude prevalence rates. An additional seven studies incorporated severity into their case definitions, while four used multiple “caseness” scores. Clearly, there is little consensus on how to operationalize severity of disorders. Equally clear is the substantial impact on prevalence rates when severity criteria and need for treatment are introduced into case definition; prevalence rates are greatly reduced, sometimes by a factor of three or more. (In a number of cases, prevalences adjusted for severity of impairment and/or need for treatment are in the range of 4%–8%.) From the perspective of planning mental health services, the policy implications of prevalences of 4%–8% compared to prevalences of 18%–22% (60) are profound.

Data Analyses and Presentation

There is an additional consideration which, although seldom discussed, has impeded progress in psychiatric epidemiology: the lack of common analytic techniques and uniform modes of presenting data (60, 61). There are still no uniform modes of presenting data from epidemiologic studies of child and adolescent disorders. Prevalence rates may be either point or period prevalences. If the latter, the referent period may vary, but typically it is 1 month, 6 months, 1 year, or lifetime. Thirty-two studies reported current prevalence (median=12.0%, mean=14.9%), another 10 studies reported 6-month prevalence (median=15.9%, mean=19.4%), and another eight reported 1-year prevalence (median=14.1%, mean=15.1%).

For estimates of prevalence to be most useful, one must know the precision of the estimate. That is, one must know the tolerable error or the size of the interval around the estimate with a specified degree of confidence (80). Given the small sample sizes in most child studies, the estimates no doubt have large confidence intervals at the 95% level. More recent publications have begun to provide such information (46, 51, 58).

Comparability across studies also would be enhanced and cumulative evidence from different studies facilitated if more child psychiatric epidemiologists employed analytic techniques commonly used in other areas of epidemiologic research. For example, in the presentation of prevalence rates for subgroups based on age, gender, or socioeconomic status, calculation and reporting of odds ratios could indicate the relative risk of disorder in specific subgroups, such as middle adolescents, males, and lower-status youths.

Strategies for the Next Phase of Research

Few would probably disagree with the conclusions by researchers such as Earls (81) and Rutter (1) that we now know a good deal about child disorders—certainly, a great deal more than we did even a decade ago. Few also would disagree that we still have much to learn. From an epidemiologic perspective there is, in fact, a myriad of the most fundamental scientific questions for which we have few or no empirical data. These basic questions focus on issues of incidence, prevalence, natural history, and etiology of psychiatric disorders in nonpatient or community populations. Of these, we note eight in particular.

1. The available data on prevalence are quite limited. For example, there are almost no data on the prevalence of clinical disorders among diverse ethnic minorities, different socioeconomic strata, and rural compared with urban populations.

2. From the perspective of prevention and treatment as well as epidemiology, understanding the natural history of child and adolescent disorders is critical, yet there are essentially no data on incidence, duration, and recurrence in community populations.

3. Comorbidity is increasingly recognized as a key phenomenological feature of psychiatric disorders among children and adults (82, 83), yet there are basically no community-based epidemiologic data on the prevalence, incidence, and natural history of comorbid disorders in children.

4. A key to understanding child disorders is understanding the role of developmental factors (76), but at present there are few data on the role of development in the manifestation of psychiatric problems, because there are few data from epidemiologic studies examining the relation between developmental milestones or stages and clinical psychiatric syndromes.

5. Ultimately, the goal of child psychiatric epidemiology is to explain the etiology of mental disorders. A necessary requisite is data from prospective, longitudinal studies assessing the roles of multiple risk factors drawn from both psychosocial and biological domains in specific disorders and the specificity of effects of these factors. Few such data are available.

6. In addition to examination of the role of risk factors in etiology, there also is a need for community-based epidemiologic studies aimed at understanding the factors affecting duration and recurrence of child disorders, in particular, factors that affect help seeking, including use of mental health and general medical services (76).

7. To date the role of biological factors has been little studied and is poorly understood vis-à-vis child and adolescent disorders. Fuller knowledge of the etiology of such disorders will require inclusion of biological and genetic variables in our conceptual models (84–86).

8. It is also essential to understand the relation between the presence or absence of psychiatric disorder and the utilization of mental health and other health and human services, and how the presence of a diagnosis and the level of impairment can be combined to provide estimates of the need for services.

How do the studies reviewed fare in terms of addressing these research issues? Poorly, overall. In our opinion, only one study (56, 57) does even a reasonable job of addressing the eight criteria outlined. That study, the Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth, is a large community-based, prospective study of the incidence and prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among 9- , 11- , and 13-year-olds. The study has a two-stage design, with 3,896 youths screened at baseline and then 1,015 assessed with a diagnostic interview. Parents also are interviewed. All subjects in the second stage are followed up annually. In addition, there is an extensive array of putative risk factors assessed, among them age, gender, socioeconomic status, rural or urban residence, physical health, child development, family burden of the child's mental health problems, maternal depression, and family psychiatric history. A key feature is linkage of the epidemiologic data with extensive data on utilization of mental health services.

Great Smoky Mountains Study procedures include assessment of both diagnostic status and functional impairment (in three domains—school, home, peers). Thus far, prevalences have been reported (56) for youths who met no diagnostic criteria and had no functional impairment (63.7%), who met diagnostic criteria but were not functionally impaired (9.1%), who did not meet diagnostic criteria but had sufficient symptoms to be impaired (16.1%), and who met both diagnostic criteria and functional impairment criteria (11.1%). Overall, 20.3% of the youths met diagnostic criteria on the basis of combined parent and child reports. At baseline, the diagnostic interview sample (N=1,015) was large enough to permit stable estimates of most major DSM-III-R diagnoses and to examine the role of major risk factors, with the exception of biological factors, which were not assessed. Major limitations are the absence of children under 9 years of age, the limited age range at baseline (ages 9, 11, and 13 years), and a sample size that on successive follow-ups will not be large enough to estimate the risk of many specific disorders or the effects of some risk factors. Still, the study stands out for its many features designed to yield maximal epidemiologic knowledge.

Where do we go from here? As Rutter (1) has noted, child psychiatric epidemiology indeed has made considerable progress in the 30 years since the landmark Isle of Wight study began. But, as we suggest in the preceding section, research on the epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorder is very much a journey in progress. The central research challenges discussed provide a point of departure for the next segment of the journey, as well as a map for at least some alternative routes that may make the trip more productive and more informative for policy and mental health services. The destination is resolution of the research questions outlined above, questions that define the limits of our current knowledge of the epidemiology of child disorders.

|

|

|

|

Received Sept. 23, 1996; revisions received June 24 and Oct. 10, 1997; accepted Dec. 1, 1997. From the School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, and the Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco. Address reprint requests to Dr. Roberts, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center, P.O. Box 20186, Houston, TX 77225. Supported in part by NIMH grant MH-46122 (Dr. Attkisson), grant MH-51687 (Dr. Roberts), and grant MH-43694 from the Center for Mental Health Services Research (Drs. Roberts and Attkisson); and by evaluation research contracts from the California State Department of Mental Health (89-70225, 90-70195, 91-71106, 92-72090, 92-72347, 93-73346, 94-74252, 94-74285, and 95-75217 (Drs. Rosenblatt and Attkisson). The authors thank Harold Baize, Nancy Mills, Juliana Ortegon, Susan De Magri, and Sue Tico for ongoing contributions to their research and scholarship.

1 Rutter M: Isle of Wight revisited: twenty-five years of child psychiatric epidemiology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1989; 28:633–653Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Lapouse R, Monk MA: An epidemiologic study of behavior characteristics in children. Am J Public Health 1958; 48:1134–1144Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Gould MS, Wunsch-Hitzig R, Dohrenwend BP: Formulation of hypotheses about the prevalence, treatment, and prognostic significance of psychiatric disorders in children in the United States, in Mental Illness in the United States: Epidemiologic Estimates. Edited by Dohrenwend BP, Dohrenwend BS, Gould MS, Link B, Neugebauer R, Wunsch-Hitzig R. New York, Praeger, 1980, pp 9–45Google Scholar

4 Links PS: Community surveys of the prevalence of childhood psychiatric disorders: a review. Child Dev 1983; 54:531–548Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Long A: Parents' reports of undesirable behavior in children. Child Dev 1941; 12:43–62Google Scholar

6 Wickman EK: Children's Behavior and Teachers' Attitudes. New York, Commonwealth Fund, 1928Google Scholar

7 Shaffer D (ed): National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, version IV. New York, Columbia University, 1996Google Scholar

8 Costello EJ: Developments in child psychiatric epidemiology: an epidemiologic study of behavior characteristics in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1989; 28:836–841Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Brandenburg NA, Friedman RM, Silver SE: The epidemiology of childhood psychiatric disorders: prevalence findings from recent studies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1990; 29:76–83Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Verhulst FC: A review of community studies, in The Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. Edited by Ver~hulst FC, Koot HM. Oxford, England, Oxford University Press, 1995, pp 146–177Google Scholar

11 Goldfarb A: Teacher ratings in psychiatric case-finding, I: methodological considerations. Am J Public Health 1963; 53:1919–1927Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Krupinski J, Baikie AG, Stoller A, Graves J, O'Day DM, Polke P: A community health survey of Heyfield, Victoria. Med J Aust 1967; 1204–1211Google Scholar

13 Rutter M, Tizard J, Whitmore K: Education, Health and Behavior: Psychological and Medical Study of Childhood Development. London, Longman Group, 1970Google Scholar

14 Werner EE, Bierman JM, French FE: The Children of Kauai: A Longitudinal Study From the Prenatal Period to Age Ten. Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press, 1971Google Scholar

15 Bjornesson S: Epidemiological investigation of mental disorders of children in Reykjavik, Iceland. Scand J Psychol 1974; 15:244–254Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Leslie SA: Psychiatric disorder in the young adolescents of an industrial town. Br J Psychiatry 1974; 125:113–124Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Rutter M, Cox A, Tupling C, Berger M, Yule W: Attainment and adjustment in two geographical areas, I: the prevalence of psychiatric disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1975; 126:493–509Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Richman N, Stevenson JE, Graham PJ: Prevalence of behaviour problems in 3-year-old children: an epidemiological study in a London borough. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1975; 16:277–287Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Minde KK: Psychological problems in Ugandan school children: a controlled evaluation. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1975; 16:49–59Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Kastrup M: Psychic disorders among pre-school children in a geographically delimited area of Aarhus county, Denmark: an epidemiological study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1976; 54:29–42Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Zimmerman-Tansella C, Minghetti S, Tacconi A, Tansella M: The Children's Behaviour Questionnaire for completion by teachers in an Italian sample: preliminary results. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1978; 19:167–173Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Earls F, Richman N: The prevalence of behaviour problems in three-year-old children of West Indian-born parents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1980; 21:99–106Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Earls F: Prevalence of behavior problems in 3-year-old children: a cross-national replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980; 37:1153–1157Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Earls F: The prevalence of behavior problems in 3-year-old children: comparison of the reports of fathers and mothers. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 1980; 19:439–452Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Connell HM, Irvine L, Rodney J: Psychiatric disorder in Queensland primary schoolchildren. Aust Paediatr J 1982; 18:177–180Medline, Google Scholar

26 McGee RM, Silva PA, Williams S: Behavior problems in a population of seven-year-old children: prevalence, stability and types of disorder: a research report. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1984; 25:251–259Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Rahim SI, Cederblad M: Effects of rapid urbanisation on child behaviour and health in a part of Khartoum, Sudan. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1984; 25:629–641Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Vikan A: Psychiatric epidemiology in a sample of 1510 ten-year-old children, I: prevalence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1985; 26:55–75Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Verhulst FC, Berden GFMG, Sanders-Woudstra JAR: Mental health in Dutch children, II: the prevalence of psychiatric disorder and relationship between measures. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1985; 324:1–45Medline, Google Scholar

30 Offord DR, Boyle MH, Szatmari P, Rae-Grant NI, Links PS, Cadman DT, Byles JA, Crawford JW, Blum HM, Byrne C, Thomas H, Woodward CA: Ontario Child Health Study, II: six-month prevalence of disorder and rates of service utilization. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:832–836Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Boyle MH, Offord DR, Hofmann HG, Catlin GP, Byles JA, Cadman DT, Crawford JW, Links PS, Rae-Grant NI, Szatmari P: Ontario Child Health Study, I: methodology. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:826–831Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 Kashani JH, Beck NC, Hoeper EW, Fallahi C, Corcoran CM, McAllister JA, Rosenberg TK, Reid JC: Psychiatric disorders in a community sample of adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:584–589; correction, 144:1114Link, Google Scholar

33 Weyerer S, Castell R, Biener A, Artner K, Dilling H: Prevalence and treatment of psychiatric disorders in 3–14-year-old children: results of a representative field study in the small rural town region of Traunstein, Upper Bavaria. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1988; 77:290–296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 Costello EJ, Costello AJ, Edelbrock C, Burns B, Dulcan M, Brent D, Janiszewski S: Psychiatric disorders in pediatric primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:1107–1116Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 Bird HR, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M, Gould MS, Ribera J, Sesman M, Woodbury M, Huertas-Goldman S, Pagan A, Sanchez-Lacay A, Moscoso M: Estimates of the prevalence of childhood maladjustment in a community survey in Puerto Rico: the use of combined measures. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:1120–1126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36 Larson CP, Pless IB, Miettinen O: Preschool behavior disorders: their prevalence in relation to determinants. J Pediatr 1988; 113:278–285Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 Moilanen I, Almqvist F, Piha J, Rasanen E, Tamminen T: An epidemiological survey of child psychiatry in Finland. Nordisk Psykiatrisk Tidsskrift 1988; 42:9–11Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Velez CN, Johnson J, Cohen P: A longitudinal analysis of selected risk factors for childhood psychopathology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1989; 28:861–864Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39 Wang Y-F, Shen Y-C, Gu B-M, Jia M-X, Zhang AL: An epidemiological study of behaviour problems in school children in urban areas of Beijing. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1989; 30:907–912Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40 Matsuura M, Okubo Y, Kato M, Kojima T, Takahashi R, Asai K, Asai T, Endol T, Yamada S, Nakane A, Kimura K, Suzuki M: An epidemiological investigation of emotional and behavioral problems in primary school children in Japan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1989; 24:17–22Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41 Esser G, Schmidt MH, Woerner W: Epidemiology and course of psychiatric disorders in school-age children—results of a longitudinal study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1990; 31:243–263Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42 Ekblad S: The Children's Behavior Questionnaire for completion by parents and teachers in a Chinese sample. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1990; 31:775–791Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43 Sawyer MG, Sarris A, Baghurst PA, Cornish CA, Kalucy RS: The prevalence of emotional and behavioral disorders and patterns of service utilization in children and adolescents. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1990; 24:323–330Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44 Luk SL, Leung PWL, Bacon-Shrone J, Chung SY, Lee PWH, Chen S, Ng R, Lieh-Mak F, Ko L, Yeung CY: Behavior disorder in pre-school children in Hong Kong: a two-stage epidemiological study. Br J Psychiatry 1991; 158:213–221Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45 Koot HM, Verhulst FC: Prevalence of problem behavior in Dutch children aged 2–3. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1991; 367:1–37Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46 Garrison CZ, Addy CL, Jackson KL, McKeown RE, Waller JL: Major depressive disorder and dysthymia in young adolescents. Am J Epidemiol 1992; 135:792–802Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47 Bergeron L, Valla JP, Breton JJ: Pilot study for the Quebec Child Mental Health Survey, part I: measurement of prevalence estimates among six to 14 year olds. Can J Psychiatry 1992; 37:374–385Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48 Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT: Prevalence and comorbidity of DSM-III-R diagnoses in a birth cohort of 15 year olds. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1993; 32:1127–1134Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49 Kasmini K, Kyaw O, Krishnaswamy S, Ramli H, Hassan S: A prevalence survey of mental disorders among children in a rural Malaysian village. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993; 87:253–257Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50 Matsuura M, Okubo Y, Kojima T, Takahashi R, Wang Y-F, Shen YC, Lee CK: A cross-national prevalence study of children with emotional and behavioral problems—a WHO collaborative study in the Western Pacific Region. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1993; 34:307–315Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51 Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Andrews J: Adolescent psychopathology, I: prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III-R disorders in high school students. J Abnorm Psychol 1993; 102:133–144Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52 Morita H, Suzuki M, Suzuki S, Kamoshita S: Psychiatric disorders in Japanese secondary school children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1993; 34:317–332Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53 Stallard P: The behaviour of 3-year-old children: prevalence and parental perception of problem behaviour: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1993; 34:413–421Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54 Fombonne E: The Chartres Study, I: prevalence of psychiatric disorders among French school-aged children. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 164:69–79Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55 Gomez-Beneyto M, Bonet A, Catala MA, Puche E, Vila V: Prevalence of mental disorders among children in Valencia, Spain. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 89:352–357Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56 Burns BJ, Costello EF, Angold A, Tweed D, Stangl D, Farmer EMZ, Erkanli A: Children's mental health service use across service sectors. Health Affairs 1995; 14(3):147–159Google Scholar

57 Costello EJ, Angold A, Burns BJ, Stangl D, Tweed D, Erkanli A, Worthman CM: The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth: goals, design, methods, and the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:1129–1136Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58 Jensen PS, Watanabe HK, Richters JE, Cortes R, Roper M, Liu S: Prevalence of mental disorder in military children and adolescents: findings from a two-stage community survey. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:1514–1524Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59 Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan MK, Davies M, Piacentini J, Schwab-Stone ME, Lahey BB, Bourdon K, Jensen PS, Bird HR, Canino G, Regier DA: The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children version 2.3 (DISC-2.3): description acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:865–877Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60 Costello EJ: Developments in child psychiatric epidemiology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1989; 28:836–841Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61 Jablensky A: Epidemiologic surveys of mental health of geographically defined populations in Europe, in Community Surveys of Psychiatric Disorders. Edited by Weissman MM, Myers JK, Ross CE. New Brunswick, NJ, Rutgers University Press, 1986, pp 257–313Google Scholar

62 Angold A, Costello EJ: Developing a developmental epidemiology, in Rochester Symposium on Developmental Psychopathology, vol 3: Models and Integrations. Edited by Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Rochester, NY, University of Rochester Press, 1991, pp 75–96Google Scholar

63 Cook TD; Campbell DT: Quasi-Experimentation: Design and Analysis Issues for Field Settings. Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1979Google Scholar

64 Lahey BB, Flagg EW, Bird HR, Schwab-Stone ME, Canino G, Dulcan MK, Leaf PJ, Davies M, Brogan D, Bourdon K, Horwitz SM, Rubio-Stipec M, Freeman DH, Lichtman JH, Shaffer D, Goodman SH, Narrow WE, Weissman MM, Kandel DB, Jensen PS, Richters JE, Regier DA: The NIMH methods for the epidemiology of child and adolescent mental disorders (MECA) study: background and methodology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:855–864Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65 Edelbrock C, Costello AJ: Structured psychiatric interviews for children, in Assessment and Diagnosis in Child Psychopathology. Edited by Rutter M, Tuma AH, Lann IS. New York, Guilford Press, 1988, pp 87–112Google Scholar

66 Shrout PE, Skodol AE, Dohrenwend BP: A two-stage approach for case identification and diagnosis: first-stage instruments, in Mental Disorders in the Community: Progress and Challenge: Proceedings of the American Psychopathological Association, 42nd ed. Edited by Barrett JE, Rose RM. New York, Guilford Press, 1986, pp 286–303Google Scholar

67 Kraemer HC; Thiemann S: How Many Subjects? Statistical Power Analysis in Research. Beverly Hills, Calif, Sage Publications, 1987Google Scholar

68 Murphy JM: Depression screening instruments: history and issues, in Depression in Primary Care: Screening and Detection. Edited by Attkisson CC, Zich JM. New York, Routledge, 1990, pp 65–83Google Scholar

69 Shrout PE: Statistical design of screening procedures. Ibid, pp 84–97Google Scholar

70 Roberts RE, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR: Screening for adolescent depression: a comparison of depression scales. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1991; 30:58–66Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71 Gutterman EM, O'Brien JD, Young JG: Structured diagnostic interviews for children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1987; 26:621–630Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

72 Richters JE: Depressed mothers and informants about their children: a critical review of the evidence of distortion. Psychol Bull 1992; 112:485–499Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

73 Connell HM, Irvine L, Rodney J: The prevalence of psychiatric disorder in rural school children. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1982; 16:43–46Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

74 Costello EJ: Primary care pediatrics and child psychopathology: a review of diagnostic, treatment and referral practices. Pediatrics 1986; 78:1044–1051Medline, Google Scholar

75 Burns BJ: Mental health service use by adolescents in the 1970s and 1980s. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1991; 30:144–150Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

76 Costello EJ, Angold A: Toward a developmental epidemiology of the disruptive behavior disorders. Developmental Psychopathology 1993; 5:91–101Crossref, Google Scholar

77 Jensen PS, Koretz D, Locke BZ, Schneider S, Radke-Yarrow M, Richters JE, Rumsey JM: Child and adolescent psychopathology research: problems and prospects for the 1990s. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1993; 21:551–580Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

78 Costello EJ, Tweed D: A Review of Recent Empirical Studies Linking the Prevalence of Functional Impairment With That of Emotional and Behavioral Illness or Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Washington, DC, Center for Mental Health Services, 1994Google Scholar

79 Canino G, Bird HR, Shrout PE, Rubio-Stipec M, Bravo M, Mar~tinez R, Sesman M, Guevara LM: The prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in Puerto Rico. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:127–133Google Scholar

80 Henry GT: Practical Sampling: Applied Social Research Methods Series, vol 21. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage Publications, 1990Google Scholar

81 Earls F: Epidemiology and child psychiatry: entering the second phase. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1989; 59:279–283Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

82 Brady EU, Kendall PC: Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Psychol Bull 1992; 111:244–255Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

83 Bird HR, Gould MS, Staghessa BM: Patterns of diagnostic comorbidity in a community sample of children aged 9 though 16 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1993; 32:361–368Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

84 Cohen S, Kessler RC, Gordon LU: Strategies for measuring stress in studies of psychiatric and physical disorders, in Measuring Stress: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists. Edited by Cohen S, Kessler RC, Gordon LU. New York, Oxford University Press, 1995, pp 3–28Google Scholar

85 Roger D: Emotion control, coping strategies, and adaptive behavior, in Stress and Emotion: Anxiety, Anger, and Curiosity, vol 15. Edited by Spielberger CD, Sarason IG, Brebner JMT, Green~glass E, Laungani P, O'Roark AM. Washington, DC, Taylor & Francis, 1995, pp 255–264Google Scholar

86 Uchino BN, Cacioppo JT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK: The relationship between social support and physiological processes: a review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychol Bull 1996; 119:488–531Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar